Liberty Matters

Interest-Group Liberalism and the Administrative State

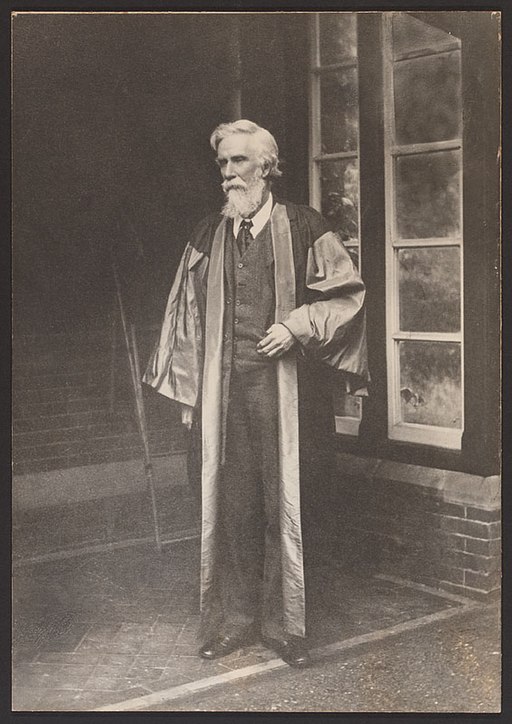

Judge Glock introduces a new (to me) insight into A. V. Dicey’s classic view of the constitutional problem of the administrative state. As Philip Hamburger has recently demonstrated, the ways that “administrative law” is unlawful are many. Glock via Dicey focuses on one fundamental problem: the immunity of government officers, which Dicey believed violated the bedrock principle of equality before the law.

Judge Glock introduces a new (to me) insight into A. V. Dicey’s classic view of the constitutional problem of the administrative state. As Philip Hamburger has recently demonstrated, the ways that “administrative law” is unlawful are many. Glock via Dicey focuses on one fundamental problem: the immunity of government officers, which Dicey believed violated the bedrock principle of equality before the law.Glock rightly points to the Trade Disputes Act of 1906, which gave British labor unions legal immunities, and which Dicey called “legalized wrongdoing.” This Act became the model for the kind of privilege that American labor leaders desired. Exemption from the antitrust laws and the abolition of the “labor injunction” came in the Norris-La Guardia Act of 1932. Federal promotion of collective bargaining came in the 1935 National Labor Relations (or Wagner) Act. (For a long time, Wagner’s bill was called the “Trade Disputes Act.”) The Supreme Court’s acceptance of the Wagner Act (hot on the heels of President Roosevelt’s threat to “pack” the Court) marked the beginning of the modern entitlement state. It is one of the shortcomings of Christopher Caldwell’s generally excellent book, The Age of Entitlement, that it does not recognize the link between this original entitlement act and the later Civil Rights Act that he says ushered in “the age,” particularly when the latter was in so many ways the product of the former.[1]

However, these acts seem to belie Dicey’s assumption of a tradition of “equality before the law”—or at least makes it appear to be more of an aspiration than a tradition. American Federation of Labor President Samuel Gompers believed that England (his native country) more readily adopted union-empowering legislation like the Trade Disputes Act precisely because it was a class-based, aristocratic society. The American insistence on legal equality was the obstacle on this side of the Pond. As the great progressive legal scholar Roscoe Pound would say in 1958, under the Wagner Act unions were free to commits torts against persons and property, interfere with the use of transportation, break contracts, deprive people of the means of livelihood, and misuse trust funds, “things no one else can do with impunity. The labor leader and labor union now stand where the king and government . . . stood at common law.” Rather than a countervailing force to limit corporate power, unions had themselves gained “a despotic centralized control.”

It is notable that the English Trade Disputes Act did not establish an administrative body like the National Labor Relations Board. Instead, British unions established a political party, the Labour Party, to look after union interests. In the United States, organized labor became the most important interest group in the mid-twentieth century Democratic party, but did not turn the Democrats into a Labor party. Indeed, many labor historians lament this fact, claiming that the American political and legal system blunted the potential for the labor movement to transform American capitalism, repeatedly “deradicalizing” the labor movement.

The radical potential of the American labor movement could be seen in the “sit-down strikes” of 1937. The strike against General Motors in Flint, Michigan, put them in the public eye, and provided the backdrop to President Roosevelt’s plan to “pack” the Supreme Court. It is not implausible that the Court’s dramatic reversal in April, 1937, upholding the Wagner Act, which almost everybody expected it to strike down, was in response to the sit-down strikes, to provide an alternative forum to resolve industrial disputes.

The American administrative law of labor highlighted the uniquely powerful place of courts and judicial review in the American administrative state. The Labor Board displayed all the constitutional pathologies of the twentieth century—the delegation of legislative power, its combination with executive and judicial power, and regulatory “capture.” Thus Congress significantly restructured the Board in the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, which was rather like an Administrative Procedure Act specifically for labor relations. The Board nevertheless remained “captured” by the unions. Law Professor Sylvester Petro described “how the NLRB repealed Taft-Hartley” in a 1958 book.[2] Thus courts had to intervene to address some of their most salient abuses.

The Wagner Act made it illegal for employers to discriminate against union labor, and thus compelled employers to bargain collectively and exclusively with unions that themselves discriminated against blacks. (Ironically, the Wagner Act introduced the term “affirmative action.” If an employer was found to violate the act, the Board could compel it to “cease and desist… and to take such affirmative action… as will effectuate the policies of this act.”)[3]The leading black civil rights organizations sought but did not obtain a non-discrimination provision in the Wagner Act. The courts began the reform of the Wagner Act. During World War Two the courts established that unions had a duty of “fair representation.” They did not have to admit blacks as members, but could not discriminate against them if they had the power to bargain for them. The Court recognized that the Wagner Act had given unions quasi-sovereign power. Though it is not usually seen as a “nondelegation” case, this was essentially what the Court did—recognized the enormous power that the Wagner Act had given to unions, and tried to hold them to a constitutional standard of equal protection.[4] The Labor Board remained hostile to civil rights issues, having been “captured” by unions that discriminated against them to one degree or another.

During and after World War Two, presidential commissions were established to prohibit racial discrimination by government contractors. Their impact was limited by the fact that the contractors had to bargain with discriminatory unions. (Many of them did use union discrimination as a convenient cop-out.) In the 1960s the government became more insistent. John F. Kennedy introduced the term “affirmative action” into his 1961 executive order, and employers began to engage in what is sometimes called “soft affirmative action”—letting minorities know that opportunities were available, advertising in black newspapers and recruiting at black colleges, adopting systematic hiring policies rather than relying on nepotism and the “old boys network.” The major change came in the “Philadelphia Plan” in the Johnson administration. First targeted at certain construction trades in particular cities, it was the first program to demand statistical profiles and “goals and timetables” for increasing minority employment.[5] This program was in keeping with Johnson’s Howard University commencement address in 1965, which called for “not just equality as a right and a theory but equality as a fact and equality as a result.” But union resistance, and a challenge by the Comptroller General that the plan violated government procurement laws, led the Johnson Labor Department to suspend the plan.

“Affirmative action” was revived by President Nixon. He intervened in Congress to prevent a legal override of his executive order. His Labor Department defended the program in the courts. (Federal district and appellate courts approved of the Philadelphia Plan; the Supreme Court did not review their decisions.) He then extended the program to all government contractors. He was accused of cynically trying to “divide and conquer” his liberal opponents by pitting the labor and civil rights movements against each other. But the administration was responding to a genuine problem in the development of the American administrative state: the creation of one entitlement (collective bargaining) had collided with the establishment of another (nondiscrimination). University of Pennsylvania Law Professor Sophia Z. Lee has recently written about this problem (without understanding it) in The Workplace Constitution: From the New Deal to the New Right (Cambridge).

The bureaucratic-judicial construction of affirmative action in the government contracting program was largely replicated in the other major employment-discrimination program, the adoption of the “disparate impact” theory under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Many scholars have echoed policy historian Hugh Davis Graham’s observation that the system of racial preferences arose out of “a closed system of bureaucratic policymaking, one largely devoid not only of public testimony but even of public awareness that policy was being made.”[6] Race had always been the great exception to equality before the law, “the very centerpiece of Dicey’s idea of the rule of law.” But rather than address that anomaly, the New Deal administrative state established a system of class-based policies that exacerbated it.[7] The controversial system of race-based affirmative action arose largely in response to that first round of administrative state-building, and has been since expanded to a host of other groups, taking the United States ever farther away from its ideals of equality before the law and rule of law.

Endnotes

[1] I address this at length in the forthcoming article, “Administered Entitlements: Collective Bargaining to Affirmative Action,” Social Philosophy and Policy.[2] Sylvester Petro, How the NLRB Repealed Taft-Hartley (Washington: Labor Policy Association, 1958).

[3] 49 Stat. 449 (1935), sec. 10(c).

[4] The leading cases were Steele v. Louisville & Nashville Railroad, 323 U.S. 192 (1944) and Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen & Enginemen, 323 U.S. 210 (1944). These cases arose under the Railway Labor Act of 1926, and were extended to the Wagner Act in 1953. See, generally, Paul Frymer, “Acting When Elected Officials Won’t: Federal Courts and Civil Rights Enforcement in the United States, 1935-85,” American Political Science Review 97 (2003).

[5] There were minor adumbrations of this approach by some New Deal agencies in the 1930s, and near the end of the Eisenhower administration’s Committee on Government Contracts.

[6] “The Great Society’s Civil Rights Legacy,” in The Great Society and the High Tide of Liberalism, ed. Sidney Milkis and Jerome M. Mileur (University of Massachusetts, 2005), 376.

[7] Paul Moreno, “An Ambivalent Legacy: Black Americans and the Political Economy of the New Deal,” Independent Review 6 (2002).

[3] 49 Stat. 449 (1935), sec. 10(c).

[4] The leading cases were Steele v. Louisville & Nashville Railroad, 323 U.S. 192 (1944) and Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen & Enginemen, 323 U.S. 210 (1944). These cases arose under the Railway Labor Act of 1926, and were extended to the Wagner Act in 1953. See, generally, Paul Frymer, “Acting When Elected Officials Won’t: Federal Courts and Civil Rights Enforcement in the United States, 1935-85,” American Political Science Review 97 (2003).

[5] There were minor adumbrations of this approach by some New Deal agencies in the 1930s, and near the end of the Eisenhower administration’s Committee on Government Contracts.

[6] “The Great Society’s Civil Rights Legacy,” in The Great Society and the High Tide of Liberalism, ed. Sidney Milkis and Jerome M. Mileur (University of Massachusetts, 2005), 376.

[7] Paul Moreno, “An Ambivalent Legacy: Black Americans and the Political Economy of the New Deal,” Independent Review 6 (2002).

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.