Liberty Matters

Response to Ruth Scurr

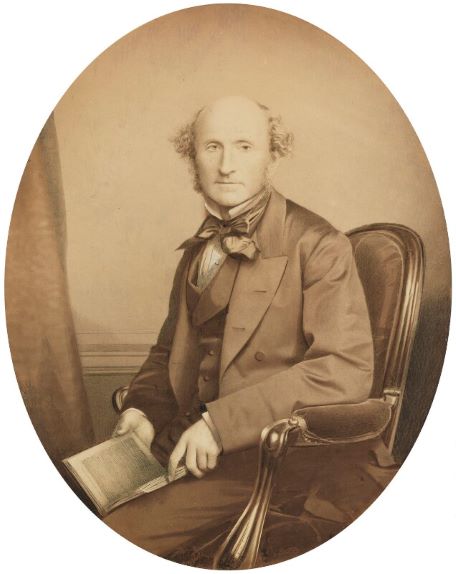

It is a pleasure to have the opportunity to read Ruth Scurr's thoughtful essay on J.S.Mill and life-writing and to be able to provide a few remarks by way of response.

It is a pleasure to have the opportunity to read Ruth Scurr's thoughtful essay on J.S.Mill and life-writing and to be able to provide a few remarks by way of response.I first read Mill's Autobiography about 50 years ago as an undergraduate student, and it is a book that I have returned to many times since. Each year I tell my own students to read it, but sadly very few do. The opening paragraph is not one to encourage interest from the passing reader or uninterested student. Indeed, in the opening sentence Mill raises the question of why he should have thought it useful to leave behind "such a memorial of so uneventful a life." Mill tells us in reply that he believed there was merit in providing "some record of an education which was unusual and remarkable," and especially so, he added, "in an age of transition in opinions." More important to Mill, however, was what he described as "a desire to make acknowledgement of the debts which my intellectual and moral development owes to other persons." Nonetheless, he wrote sternly, "the reader whom these things do not interest has only himself to blame if he reads farther, and I do not desire any other indulgence from him than that of bearing in mind, that for him these pages were not written." Take it or leave it, in other words.

Given this forbidding welcome to the reader it is hardly surprising, as Scurr reminds us, that Thomas Carlyle, a man not unknown for rhetorical excess, should describe Mill's Autobiography as "the life of a logic-chopping machine." Yet, as Scurr tells us, "there is evidence in the text and elsewhere that Mill thought and felt deeply about life-writing." It is good to have this stated clearly, for surely Carlyle was wrong. Rather, the Autobiography reads as an brutally honest and, at times, deeply painful account of how to escape, with very little help from those around him, such an awful condition--a condition, by Mill's own account, "not altogether untrue" of him for two or three years when he was a young man.

The joy of reading such a well-crafted essay as that presented to us by Ruth Scurr is that it helps the reader to see a well-known text anew, and this certainly is the case here. Anyone who has read the Autobiography will be familiar with Mill's truly daunting account of his early education and the prodigious amount of reading involved, all beautifully summarised in Mill's memorable remark that "in my eighth year I commenced learning Latin." Prior to this had come Greek, arithmetic, Hume, Gibbon, ecclesiastical history, a couple of favourite travel books, the occasional lightweight read such as Robinson Crusoe, and much else! One thing that struck me here was that Mill never seemed simply to dip into an author's work. As Mill recounted later in the Autobiography, he did not just read occasional bits of Byron but "the whole of Byron" (with little good to him apparently). The same was true of Herodotus and many more of the authors Mill cites.

Ruth Scurr however starts by drawing our attention to a body of reading that I had previously overlooked: what Mill described as his introduction to "poetic culture of the most valuable kind, by means of reverential admiration for the lives and characters of heroic persons.". Interestingly, this passage comes immediately after a page or more where Mill recalls that he and his fellow band of philosophic radicals had found no room for "the cultivation of feeling" and consequently had been characterised by "an undervaluing of poetry, and of the Imagination generally as an element of human nature." Scurr's drawing our attention to this body of work is of considerable importance as, if true, it provides the basis for a very different account of Mill's own intellectual journey during the crucial period when he sought to break free from some, if not all, of the beliefs he had acquired at the feet of his father. In particular, as Scurr states explicitly, "it was to these texts, and not to poetry or music, that Mill turned."

Moreover, thanks to Scurr, one gets a sense of the impact of these texts upon a young man who, by his own account, was in an emotionally febrile state. Earlier in the text, Socrates appears as someone for whose character Mill had a "deep respect" and who "stood in [his] mind as a model of ideal excellence," an opinion, Mill tells us, he had acquired from reading the Memorabilia of Xenophon with his father. Indeed, Mill adds that his father's "moral inculcations" were very much those of the Socratici viri. Now, with Mill rushing towards a mental crisis of monumental proportions, Socrates, along with Plutarch, figures as an early player in the "enlargement" of his "intellectual creed." So too, Mill tells us, did a reading of "some modern biographies," with pride of place given to Condorcet's Life of Turgot.

This section of Ruth Scurr's essay is brilliantly done, expanding at some length on what is no more than half a paragraph in Mill's original text. What Mill tells us there, and what Scurr explains with great lucidity, is that this book cured him of "his sectarian follies" and that, as a consequence of reading it, he "left off designating [himself] and others as Utilitarians." Scurr adds that Mill's distinction between casting off his outer "collective designation" and getting rid of his "real inward sectarianism" (which, according to Mill, came later) is "subtle and self-knowing."

Clearly, something big was going on in Mill's intellectual development. Scurr claims, in my view with some exaggeration, that "Turgot's example set Mill free intellectually." She further argues that, after the crisis, Mill "followed a free intellectual path of thought and feeling." I disagree. My view remains that the tragedy of Mill's life lies in the fact that he could not free himself from the shackles of a utilitarian upbringing. Scurr herself writes: "Mill found in Condorcet's Vie de M. Turgot a powerful argument for distancing himself from utilitarianism, without rejecting all or any of its truths." What sort of distancing is this if it amounts to no more than renouncing the outward name? Numerous examples exist of the way in which Mill failed to escape from the intellectual clutches of his father and the ubiquitous Mr Bentham. One such was the complete absence of any religious belief "in the ordinary acceptation of the term," something his father compared "not to a mere mental delusion but to a great moral evil." More broadly, Mill spent the greater part of his subsequent intellectual career seeking to patch up a philosophy that arguably did not deserve to be saved from its critics. Mill was right: Bentham was "a systematic and accurately logical half-man" who never saw that man was "a being capable of spiritual perfection as an end." Yet, what did we get? Nothing more (in Mill's famous image) than the fabric of old and taught opinions giving way in fresh places, a fabric never allowed to fall to pieces, and one incessantly woven anew. Crucially, Mill adds to this: "I never, in the course of my transition, was content to remain, for ever so short a time, confused and unsettled." There spoke the son of a man of fixed and firm, not to say unbending, opinions.

Yet Ruth Scurr is surely right to characterise this moment as one where Mill began "to question the doctrines of his father and his father's friend, Jeremy Bentham." One can therefore easily empathise with Mill's tearful reaction to reading Marmontel's Memoirs and its account of the early death of his father. Who among us would not feel similarly moved? Yet, for Mill, the scene inspired the lifting of a burden, a relief from a state of irredeemable wretchedness, combined with the realisation that "the ordinary incidents of life could again give [him]some pleasure." Thus, as Mill put it, "the cloud generally drew off and I again enjoyed life."

Again, Ruth Scurr is right to comment that Mill "never directly criticises his father," and she is right too, in her final paragraph, to indicate how determined he was to defend his father's reputation from unfair misrepresentation. Yet here is the drama and the pain in the life-writing that is Mill's Autobiography. Scurr quotes a passage where Mill indicates that his education, and therefore his boyhood (as Mill's boyhood consisted of nothing else) was one not of love but of fear. She could have quoted much more of a similar hue with ease. His father, Mill tells us, was not a man to side with "laxity or indulgence." The element "chiefly deficient in his moral relationship to his children was that of tenderness." His temper was "constitutionally irritable." Many, Mill wrote, were "the effects of this bringing-up in the stunting of my moral growth."

Sadly, Mill concluded (in an early draft of the text) that such an upbringing was not unusual among the English families of his day where, as Mill wrote, "genuine affection is altogether exceptional." That he also lacked another "rarity in England, a really warm hearted mother" must have only added to his childhood misery. No wonder Harriet Taylor was lavished with such heartfelt and exaggerated praise.

Jeremy Jennings is Professor of Political Theory at King's College London where, until recently, he was also Head of the School of Politics and Economics. Prior to his appointment he held a position at Queen Mary University of London and was Vincent Wright Professor at the Fondation Nationale des Sciences Politiques in Paris (where he retains a Visiting Professor). Jeremy Jennings has written extensively on the history of political thought, publishing among others texts Revolution and the Republic: A History of Political Thought in France since the Eighteenth Century (OUP: 2011) and (with Michael Moriarty) The Cambridge History of French Thought (CUP: 2019). He is presently completing a monograph entitled Travels with Alexis de Tocqueville.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.