Liberty Matters

The Changing Vocabulary of Class Part 1: English Classical Liberals and Radicals

In a previous post I said that Steve Davies’ use of Ngrams to plot the frequency of use and time specificity of the terms “industrious classes” and “idle classes” prompted me to do the same for some other terms used by classical liberals in their theory of class. In addition to “idle” curiosity” I also had an “industrious” purpose in mind.

In a previous post I said that Steve Davies’ use of Ngrams to plot the frequency of use and time specificity of the terms “industrious classes” and “idle classes” prompted me to do the same for some other terms used by classical liberals in their theory of class. In addition to “idle” curiosity” I also had an “industrious” purpose in mind.My hunch is that one reason for the success of Marxist notions of class since the appearance of The Communist Manifesto in 1848 was how quickly Marxists and their supporters were able to settle on a set of key terms to describe their theory, terms such as the capitalist class, the working class, the proletariat, the bourgeoisie, and so forth. Classical liberals on the other hand were not able to settle on a similar set of limited terms to describe their ideas about rule and exploitation by a politically privileged elite. When they did use terms to describe their ideas they were very time specific, thus making the ideas behind them seem appear idiosyncratic and perhaps even quaint as the century wore on.

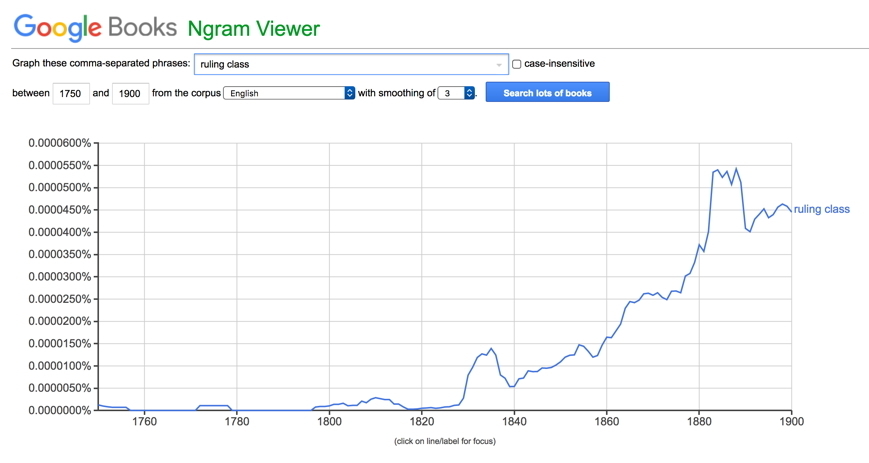

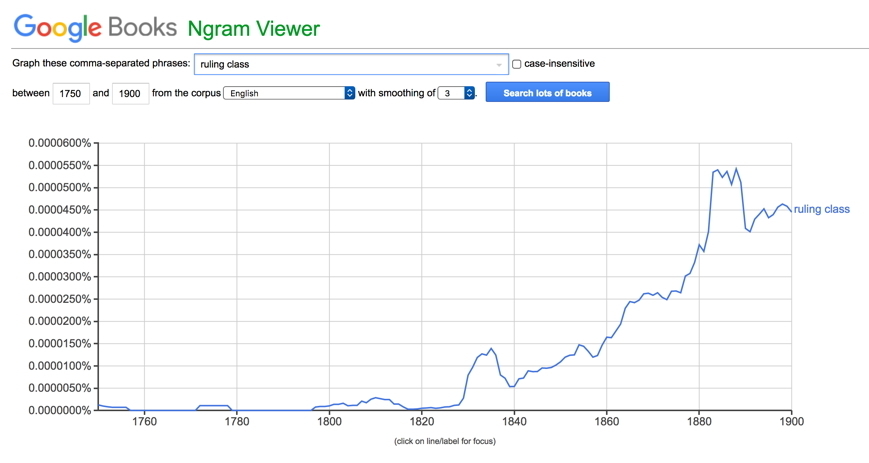

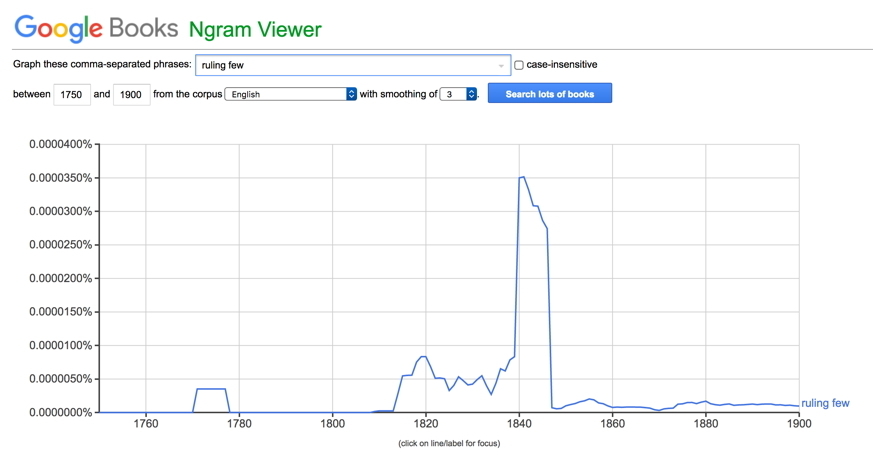

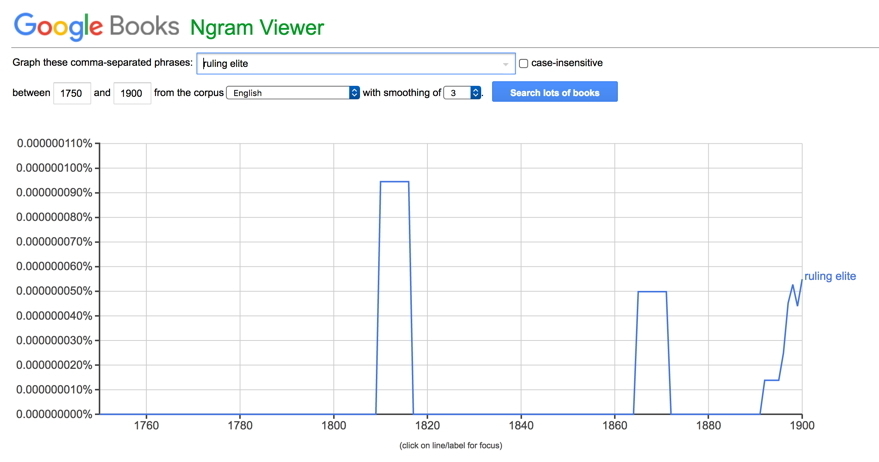

By the end of the 19th century the generic notion of “the ruling class” had become commonly used, most probably as part of a socialist view of class domination (whether Marxist or Laborite), as the graph below indicates (the time period is between 1750 to 1900 for all the graphs I generated).

|  Generic notion of “the ruling class”

Generic notion of “the ruling class”

Generic notion of “the ruling class”

Generic notion of “the ruling class”

The following are some examples selected from my larger list of CLCA theorists, in this post focusing on English Classical Liberal and Radical word usage.

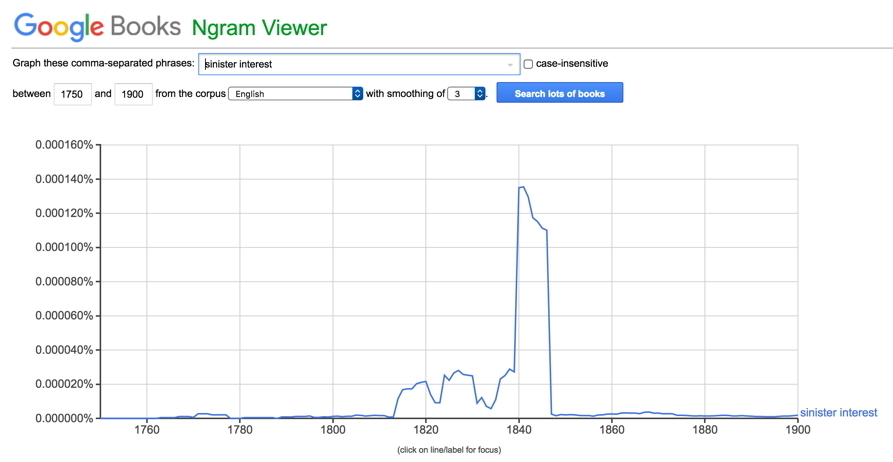

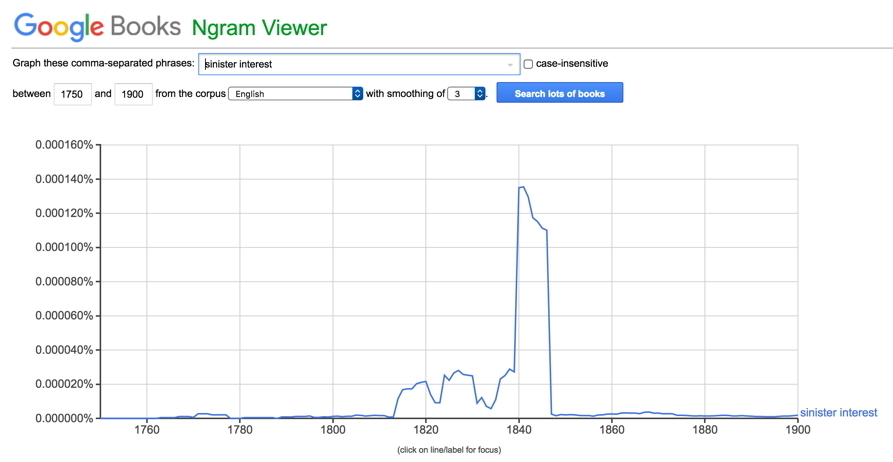

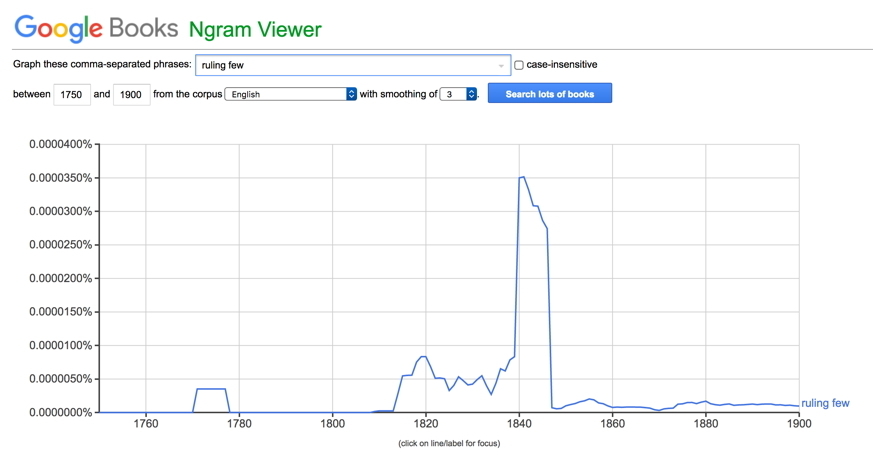

The Philosophic Radicals around Jeremy Bentham and James Mill developed their own unique vocabulary dealing with class with such terms as “the sinister interest” and “the ruling few”. Use of these terms reached a peak in the late 1830s after the success of the campaign for electoral reform with the passage of the First Reform Act in 1832 which ushered in a series of liberal reforms including the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846. After that, the use of the Benthamite vocabulary of class practically disappeared - along with, I would argue, their notion of class.

|  Benthamite term - “the sinister interest”

Benthamite term - “the sinister interest”

| Benthamite term - “the ruling few”

Benthamite term - “the ruling few”

Benthamite term - “the sinister interest”

Benthamite term - “the sinister interest”|

Benthamite term - “the ruling few”

Benthamite term - “the ruling few”

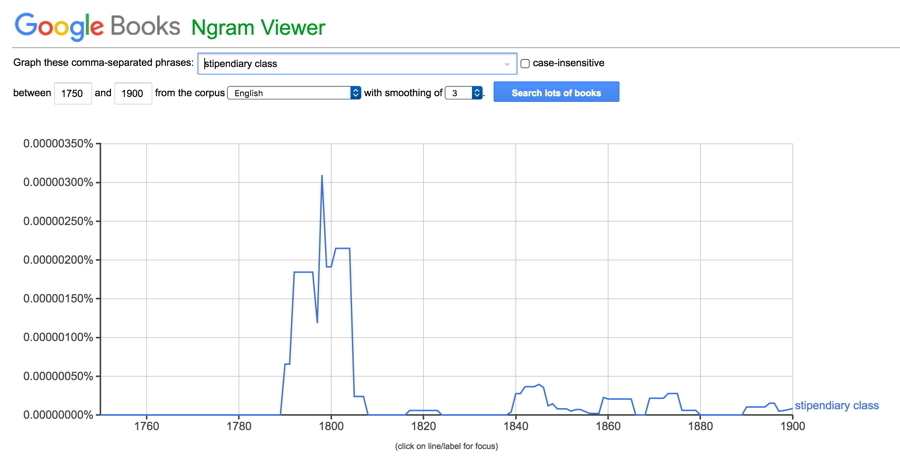

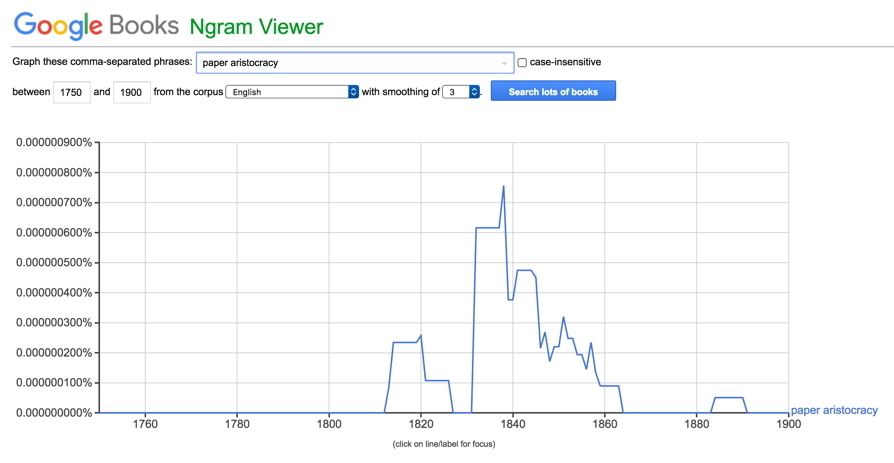

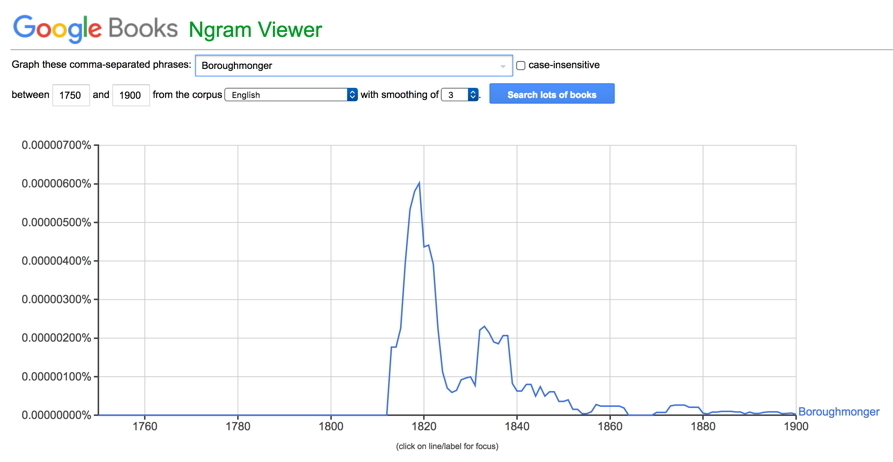

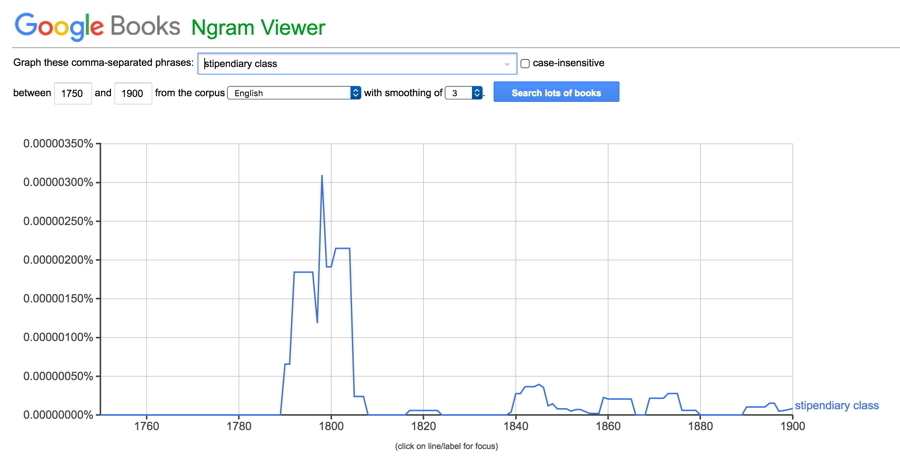

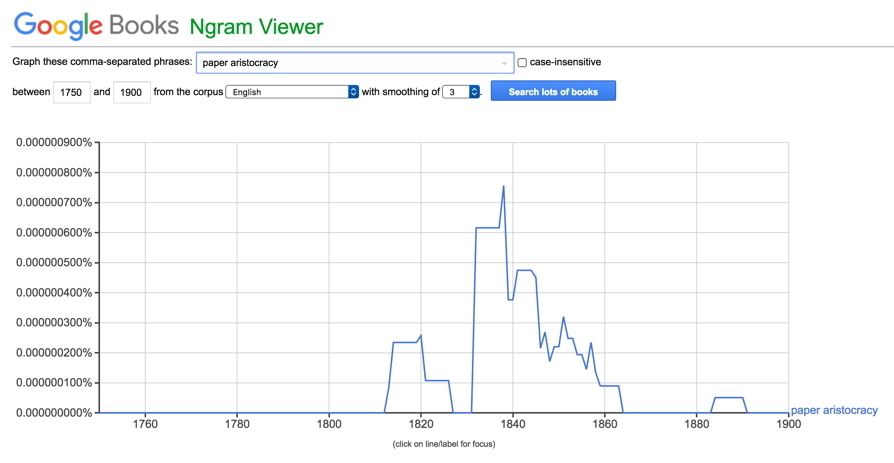

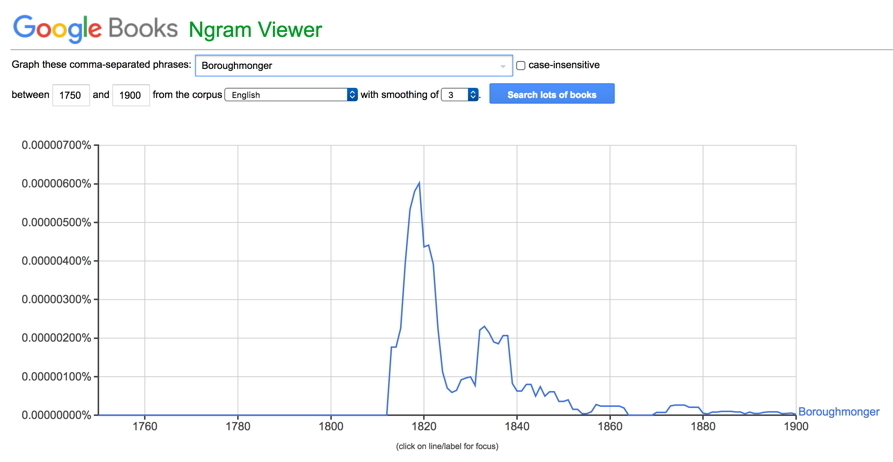

Other terms which were common among late 18th and early 19th century radicals were the physiocrat Turgot’s idea of “the stipendiary class” (also used by English speaking authors), those who lived from incomes (stipends) from government service or payments on government loans (peaked in the 1790s); and William Cobbett’s term “paper aristocracy” also used to describe those who lived off the returns of government loans (peaked in 1820 and again in the 1830s), and “boroughmongers” who were able to control elections to the House of Commons by using the seats which were attached to their extensive land-holdings (peaked in 1820 and again during the agitation for the Reform Act of 1832).

|  Turgot’s “the stipendiary class”

Turgot’s “the stipendiary class”

| William Cobbett’s idea of the “paper aristocracy”

William Cobbett’s idea of the “paper aristocracy”

| William Cobbett’s term “boroughmonger”

William Cobbett’s term “boroughmonger”

Turgot’s “the stipendiary class”

Turgot’s “the stipendiary class”|

William Cobbett’s idea of the “paper aristocracy”

William Cobbett’s idea of the “paper aristocracy”|

William Cobbett’s term “boroughmonger”

William Cobbett’s term “boroughmonger”

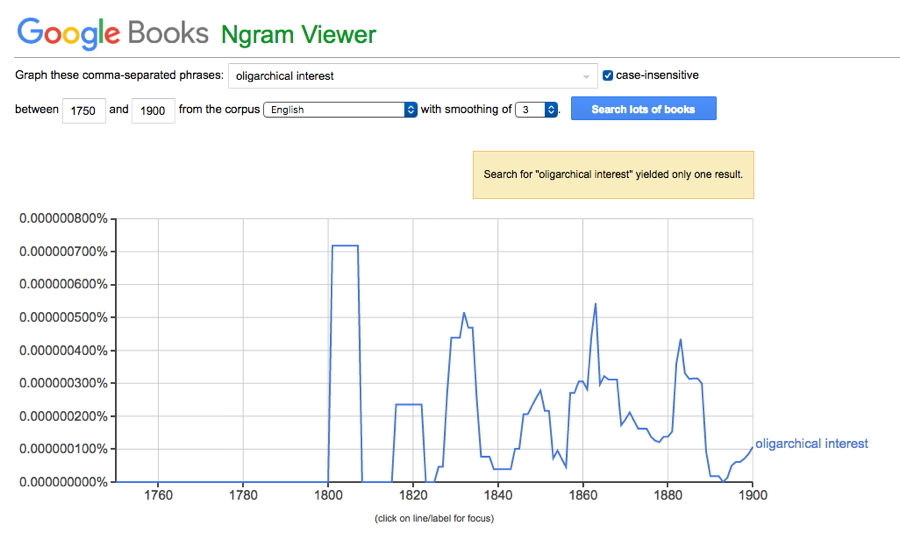

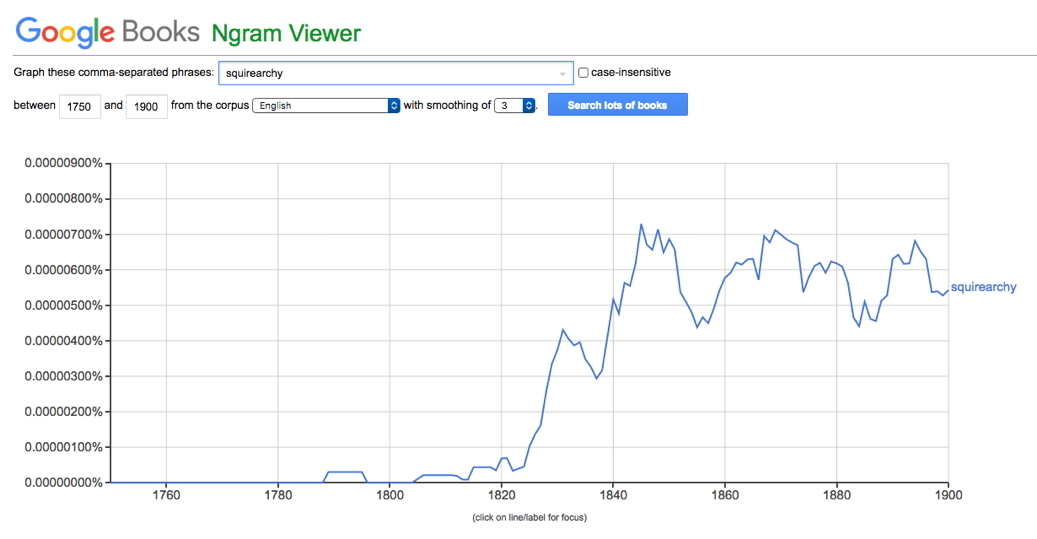

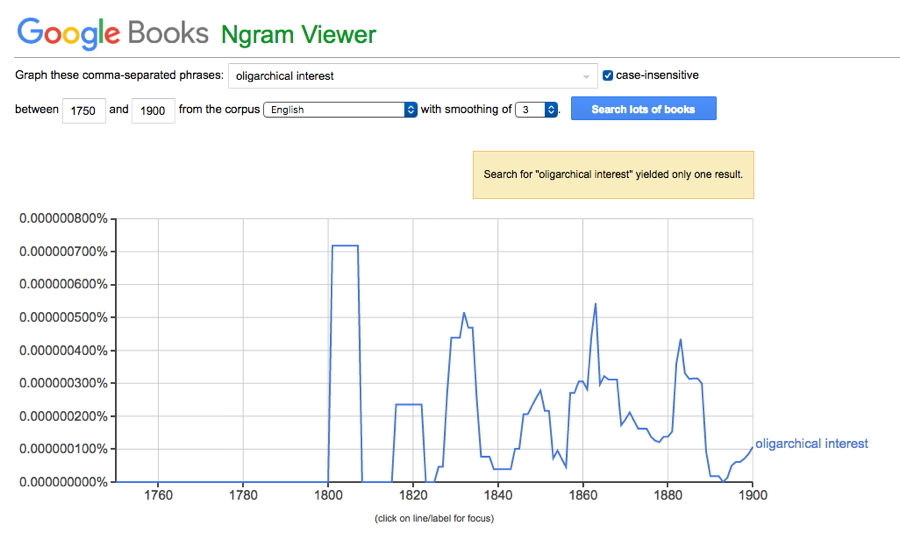

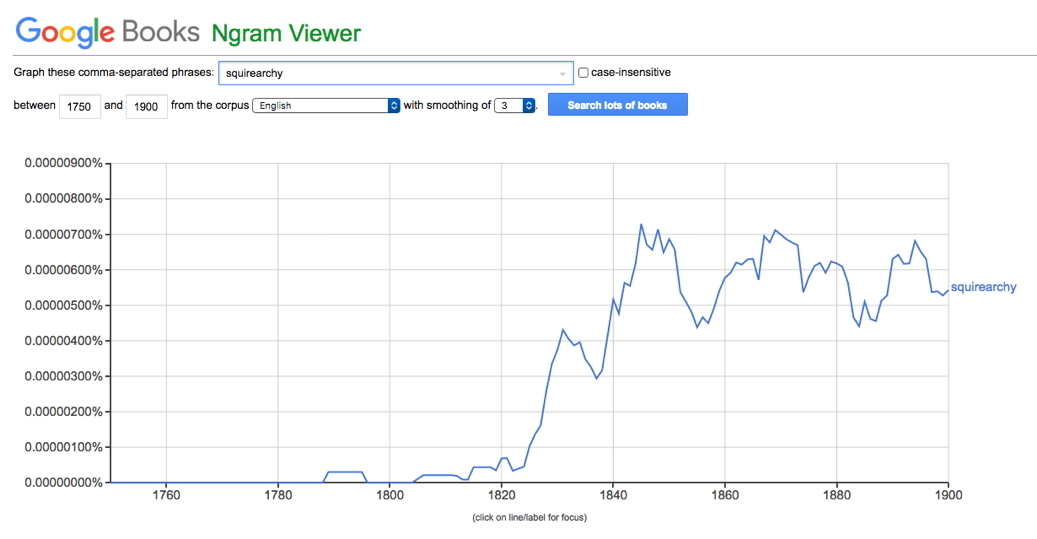

Two exceptions to this tendency for certain terms to peak at the time of some specific piece of legislative reform and then die out afterwards seems to be John Wade’s (a Radical) use of the term “oligarchical interest” with which he used to describe English elites between the 1820s and 1840s, which also had a use periodically throughout the rest of the 19th century when his form of Radicalism had largely disappeared. The same goes for Richard Cobden’s use of the term “squirearchy” to describe the large landowners who benefitted from agricultural protectionism and their control of elections to the unreformed House of Commons. Thus reached a peak during the campaign against the Corn Laws in the 1840s but continued to be quite widely used throughout the rest of the century. It is likely that these terms appealed to other radicals and socialists who used them frequently later in the century.

|  John Wade’s and the Radical’s idea of “oligarchical interest”

John Wade’s and the Radical’s idea of “oligarchical interest”

| Richard Cobden’s term “squirearchy”

Richard Cobden’s term “squirearchy”

John Wade’s and the Radical’s idea of “oligarchical interest”

John Wade’s and the Radical’s idea of “oligarchical interest”|

Richard Cobden’s term “squirearchy”

Richard Cobden’s term “squirearchy”

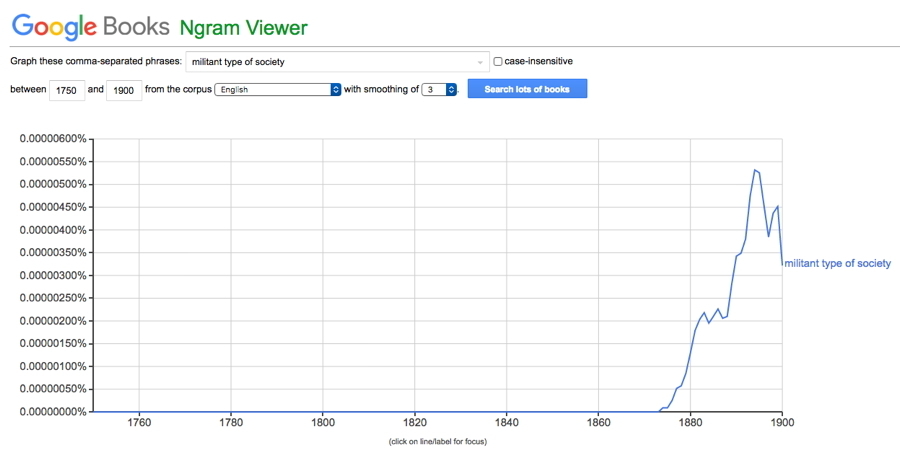

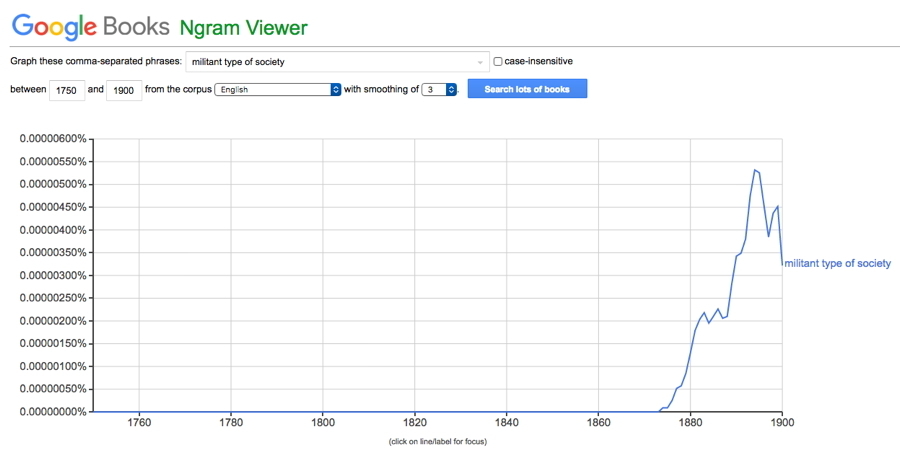

Later in the century, beginning in the 1870s and continuing for another 20 years, Herbert Spencer began to write his monumental works on political sociology in which he developed ideas like “the militant type” and the “industrial type” of society. The use of the term “militant type of society” peaked in the early 1880s and again around 1890. The graph for the term "industrial type of society" matches this almost exactly, suggesting the two were used as a pair.

|  Herbert Spencer on “the militant type of society”

Herbert Spencer on “the militant type of society”

Herbert Spencer on “the militant type of society”

Herbert Spencer on “the militant type of society”

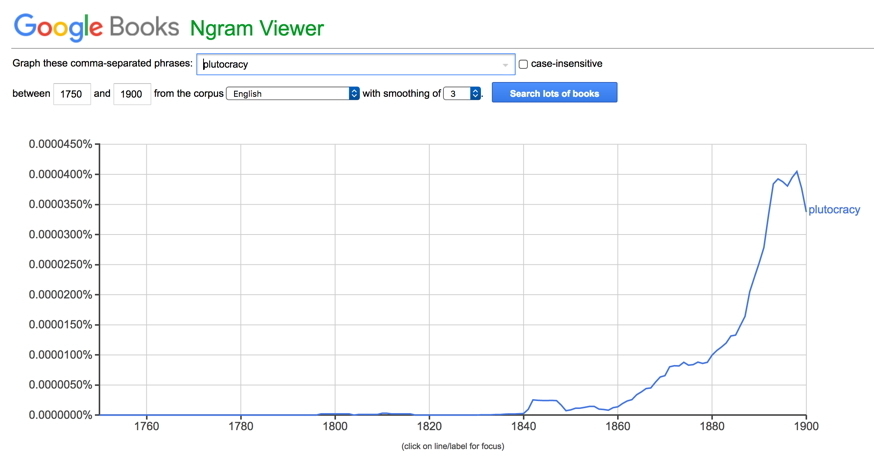

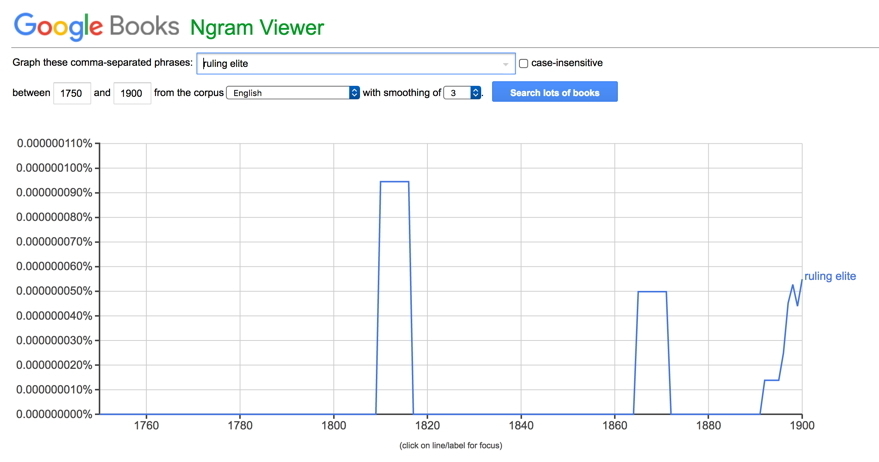

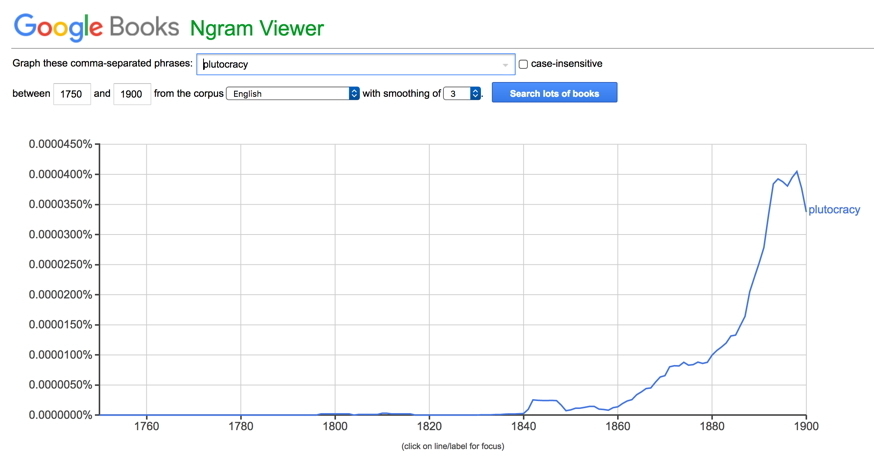

Two other rather generic terms which became popular in the late 19th century are “plutocracy” which was used by the American sociologist William Graham Sumner (peaking in the 1890s) and “ruling elite” which was taken up by Vifredo Pareto in the late 1890s (his notion of “the circulation of elites”). This is another example of a term used by both Classical Liberals and as well as by others and which quickly lost any specifically liberal connotation it might have had.

|  Sumner on “plutocracy”

Sumner on “plutocracy”

| Pareto and "the ruling elite”

Pareto and "the ruling elite”

Sumner on “plutocracy”

Sumner on “plutocracy”|

Pareto and "the ruling elite”

Pareto and "the ruling elite”

I believe that CLCA was hampered by the lack of a commonly accepted vocabulary with which to discuss class rule by privileged elites which put them at a serious disadvantage compared to the Marixts and socialists. This reflects the gradual loss of interest CLs had in this idea as the century wore on as well as the fact that class analysis was never fully integrated into modern CL thought as it seemed to be on the verge of doing earlier in the 19th century.

In another post I will examine some Ngrams concerning French Classical Liberal ideas about class analysis which showed similar divergent use of terminology.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.