The Works of Bastiat in Chronological Order 2: The Paris Writings I 1844-1848

Part 2: The “Paris” Writings I: Bastiat and the Free Trade Movement (Nov. 1844 - Feb. 1848)

[Updated: 22 June, 2017 of a "work in progress"]

Note: We have added final draft versions of material which will appear in the Collected Works, vol.3 "Economic Sophisms and WSWNS"; and vol. 4 "Miscellaneous Writings on Economics."

|

|

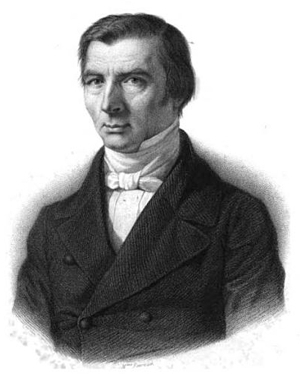

Rue Richelieu and the Molière fountain, Paris where the Guillaumin publishers were located |

|

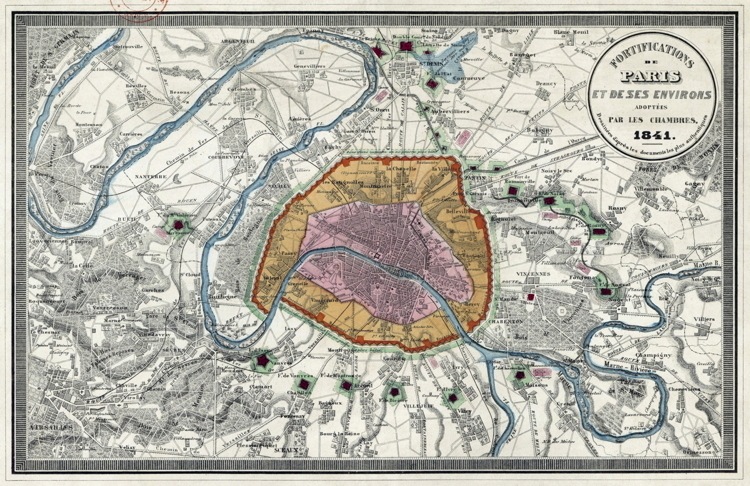

Map of Paris in 1841 showing the Octrois customs gates which were built in the 1780s (pink) and the planned military walls and forts (orange and red) which were constructed between 1841-44. Thus, when FB came to Paris in May 1845 they would have only recently been completed. |

Introduction to the Collected Works in Chronological Order

Frédéric Bastiat’s 6 volume Collected Works published by Liberty Fund is a thematic collection.

- Vol. 1: The Man and the Statesman: The Correspondence and Articles on Politics, translated from the French by Jane and Michel Willems, with an introduction by Jacques de Guenin and Jean-Claude Paul-Dejean. Annotations and Glossaries by Jacques de Guenin, Jean-Claude Paul-Dejean, and David M. Hart. Translation editor Dennis O’Keeffe (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2011). /titles/2393.

- Vol. 2: The Law, The State, and Other Political Writings, 1843–1850, Jacques de Guenin, General Editor. Translated from the French by Jane Willems and Michel Willems, with an introduction by Pascal Salin. Annotations and Glossaries by Jacques de Guenin, Jean-Claude Paul-Dejean, and David M. Hart. Translation Editor Dennis O’Keeffe. Academic Editor, David M. Hart (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2012). /titles/2450.

- Vol. 3: Economic Sophisms and “What is Seen and What is Not Seen”. Jacques de Guenin, General Editor. Translated from the French by Jane and Michel Willems, with a foreword by Robert McTeer, and an introduction and appendices by the Academic Editor David M. Hart. Annotations and Glossaries by Jacques de Guenin, Jean-Claude Paul-Dejean, and David M. Hart. Translation Editor Dennis O'Keeffe. (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2017). (Not yet online.)

- Vol. 4: Miscellaneous Works on Economics (forthcoming)

- Vol. 5: Economic Harmonies (forthcoming)

- Vol. 6: The Struggle Against Protectionism: The English and French Free-Trade Movements (forthcoming)

We are also creating a chronological version of Bastiat’s writings which only be available online. As the printed version becomes available in digital form we will add it to the chronological version. Thus, this is a work in progress. There is a complete list of all of Bastiat’s writings in order of appearance here. We have divided Bastiat’s works into 4 parts based upon the key periods and events in his life:

- Early Writings: The Bayonne and Mugron Years, 1819–1844

- The “Paris” Writings I: Bastiat and the Free Trade Movement (Oct. 1844 - Feb. 1848)

- The “Paris” Writings II: Bastiat the Politician, Anti-Socialist, and Economist (Feb. 1848 - Dec. 1850)

- The Unfinished Treatises: The Social and Economic Harmonies and The History of Plunder (1850–51)

For further information, see:

- the LF published edition of Bastiat’s Collected Works in 6 vols.

- the main Bastiat page in the OLL

- the Reader’s Guide to the Works of Frédéric Bastiat (1801–1850)

- the Liberty Matters discussion of Bastiat: Lead essay by Robert Leroux, “Bastiat and Political Economy” (July 1, 2013) with response essays by Donald J. Boudreaux, Michael C. Munger, and David M. Hart. </pages/bastiat-and-political-economy.

- Essays and other material about Bastiat

- Table of Contents of Bastiat’s Letters, Articles, and Books Listed in Chronological Order

The abbreviations used in this paper:

- 1847.02.14 = the work was published on Feb. 14, 1847

- ACLL = the English Anti-Corn Law League (1838-46)

- AEPS = L'Annuaire de l'économie politique et statistique (published by Guillaumin)

- ASEP = Annales de la Société d'Économie Politique. Publiées sous la direction de Alph. Courtois fils, secrétaire perpétuel, Tome premier 1846-1853 (Paris: Guillaumin,1889).

- CRANC = Compte rendu des séances de l'Assemblée Nationale Constituante

- CRANL = Compte rendu des séances de l'Assemblée Nationale Législative

- CF = Le Courrier française

- CH = Letters from Lettres d'un habitant des Landes, Frédéric Bastiat. Edited by Mme Cheuvreux. (1877)

- CW = the Collected Works of Frédéric Bastiat (Liberty Fund edition)

- CW1 = volume 1 of The Collected Works of Frédéric Bastiat

- OC = Oeuvres complètes de Frédéric Bastiat (Paillottet/Guillaumin edition)

- OC1.9 = the 9th article in vol. 1 of the Oeuvres complètes

- DEP = Dictionnaire d'économie politique

- DMH = text discovered by David M. Hart which is not in Paillottet's OC

- EH = Economic Harmonies

- EH1 = Economic Harmonies - the incomplete edtion publlished by FB during his lifetime in Jan. 1850 (11 chaps.)

- EH2 = Economic Harmonies - the expanded edtion with 22 chaps. publlished by Paillottet and Fontenay in July 1851

- Encyclopédie du dix-neuvième siècle (1846) = Encyclopédie du dix-neuvième siècle: répertoire universel des sciences, des lettres et des arts avec la biographie de tous les hommes célèbres, ed. Ange de Saint-Priest (Impr. Beaulé, Lacour, Renoud et Maulde, 1846)

- ES1 = Economic Sophisms. First Series (published Jan. 1846)

- ES1.10 = the tenth essay in ES1

- ES2 = Economic Sophisms. Second Series (published Jan. 1848)

- ES3 = Economic Sophisms. Third Series (compiled and published by LF in 2017 in CW3)

- FEE = Foundation for Economic Education

- JB = the journal Jacques Bonhomme (June 1848)

- JCPD = the original document was unpublished and is in the possession of Jean-Claude Paul-Dejean

- JDD = Journal des débats

- JDE = Journal des Économistes

- LÉ = Le Libre-Échange

- n.d. = no date of publication is known

- OC1 = Oeuvres complètes de Frédéric Bastiat, ed. Prosper Paillottet in 6 vols. (1854–55)

- OC2 = 2nd edition of Oeuvres complètes de Frédéric Bastiat, ed. Prosper Paillottet in 7 vols. (1862–64)

- PES = Political Economy Society (Société d'économie politique)

- PP = Prosper Paillottet, the editor of FB's OC

- RF = La République française Feb.-March 1848)

- Ronce = P. Ronce, Frédéric Bastiat. Sa vie, son oeuvre (Paris: Guillaumin, 1905).

- SP = La Sentinelle des Pyrénées

- PES = Political Economy Society (Société d'Économie Politique)

- T = either means "volume" (tome) or "Text" ID number (as in T.28)

- T.1 = text number one in the chronological table of contents of his writings

- WSWNS = What Is Seen and What Is Not Seen

The full method of citation for Bastiat’s writings (which is sometimes abbreviated in this article for reasons of space):

- T.102 (1847.01.17) "L'utopiste" (The Utopian) [Le Libre-Échange, 17 January 1847] [OC4.2.11, pp. 203–12] [ES2 11, CW3, pp. 187-98]

- text number in chronological ToC, date, French title, English title, place and date of original publication, location in French OC, location in ES, location in LF's CW volume.

- Letter 3. Bayonne, 18 March 1820. To Victor Calmètes [OC1, p. 3] [CW1, pp. 28-30]

- letter number in CW1, place and date letter written, recipient, location in OC, location in LF CW

Table of Contents

Recently added items are in BOLD [from CW4 draft 16 June, 2017].

- Letter 32. Mugron, 24 Nov. 1844. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 33. Mugron, 24 Nov. 1844. To Horace Say

- Letter 216: Letter to Félix Coudroy (1845) [CW4 draft - 16 June 2017]

- Letter 34. Mugron, 7 March 1845. To M. Ch. Dunoyer

- Letter 35. Mugron, 7 March 1845. To M. Al. de Lamartine

- Letter 36. Mugron, 8 Apr. 1845. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 37. Paris, May 1845. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 38. Paris, 23 May 1845. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 39. Paris, 5 June 1845. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 40. Paris, 16 June 1845. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 41. Paris, 18 June 1845. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 42. Paris, 3 Jul. 1845 (11pm). To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 43. London, Jul. 1845. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 44. London, 8 Jul. 1845. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 45. Paris, 29 Jul. 1845. To M. Paulton

- Letter 46. Mugron, 2 Oct. 1845. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 47. Mugron, 24 Oct. 1845. To M. Potonié

- Letter 48. Mugron, 13 Dec. 1845. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 49. Mugron, 20 Dec. 1845. To Alcide Fonteyraud

- Letter 50. Mugron, 13 Jan. 1846. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 51. Mugron, 9 Feb. 1846. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 52. Bordeaux, Feb. 1846. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 53. Bordeaux, 19 Feb. 1846. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 54. Bayonne, 4 March 1846. To Victor Calmètes

- Letter 55. Paris, 16 March 1846. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 56. Paris, 22 March 1846. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 57. Paris, 25 March 1846. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 58. Paris, 2 Apr. 1846. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 59. Paris, 11 Apr. 1846. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 60. Paris, 18 Apr. 1846. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 61. Paris, 3 May 1846. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 62. Paris, 4 May 1846. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 63. Paris, 24 May 1846. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 64. Paris, 25 May 1846. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 65. Mugron, 25 June 1846. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 66. Bordeaux, 21 Jul. 1846. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 67. Bordeaux, 22 Jul. 1846. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 68. Paris, 23 Sept. 1846. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 69. Paris, 29 Sept. 1846. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 70. Paris, 1 Oct. 1846. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 71. Paris, 22 Oct. 1846. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 72. Paris, 22 Nov. 1846. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 73. Paris, 25 Nov. 1846. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 74. Paris, 20 Dec. 1846. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 75. Paris, 25 Dec. 1846. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 76. Paris, 10 Jan. 1847. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 77. Paris, 11 March 1847. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 78. Paris, 20 March 1847. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 79. Paris, 20 Apr. 1847. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 80. Paris, 5 Jul. 1847. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 81. Paris, Aug. 1847. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 82. Mugron, Monday, Oct. 1847. To Horace Say

- Letter 83. Paris, 15 Oct. 1847. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 84. Paris, 9 Nov. 1847. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 85. Paris, 5 Jan. 1848. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 86. Paris, 17 Jan. 1848. To Madame Schwabe

- Letter 87. Paris, 24 Jan. 1848. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 88. Paris, 27 Jan. 1848. To Madame Schwabe

- Letter 89. Paris, 13 Feb. 1848. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 90. Paris, 16 Feb. 1848. To Madame Schwabe

Bastiat's Writings in 1845

- T.21 [1845.??] "Other Questions submitted to the General Councils of Agriculture, Manufactures, and Commerce, in 1845" [CW6 - to come]

- T.22 (1845.??) "The Elections. A Dialog between a deep-thinking Supporter and a Countryman"

- T.23 [1845.02.15] "Letter from an Economist to M. de Lamartine. On the occasion of his article entitled: The Right to a Job" (Feb. 1845, JDE) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.20 [1845.03] "On the Book by M. Dunoyer. On The Liberty of Working" (March, 1845) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.317 [1845.03.15] "Introduction and Post Script to Economic Sophisms" (March 1845, JDE) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.24 [1845.04.15]" Economic Sophisms: Abundance and Scarcity" (JDE, April 1845) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.25 [1845.04.15] "Economic Sophisms: Obstacle and Cause" (JDE, April 1845) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.26 [1845.04.15] "Economic Sophisms: Effort and Result" (JDE, April 1845) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.27 [1845.06] "Introduction" to Cobden and the League (Guillaumin, 1845) [CW6 - to come]

- T.28 [1845.06.15] "The Economic Situation of Great Britain: Financial Reforms and Agitation for Commercial Freedom" (JDE, June 1845)

- T.29 [1845.07.15] "Equalizing the Conditions of Production" (JDE, July 1845) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.30 [1845.07.15] "Our Products are weighed down with Taxes" (JDE, July 1845) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.31 [1845.08.15] "On the Future of the Wine Trade between France and England" (JDE, Aug., 1845) [CW6 - to come]

- T.32 [1845.10.15] "Economic Sophisms (cont.): VI. The Balance of Trade" (JDE, Oct., 1845) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.33 [1845.10.15] "Economic Sophisms (cont.): VII. Petition by the Manufacturers of Candles, etc." (JDE, Oct., 1845) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.34 [1845.10.15] "Economic Sophisms (cont.): VIII. Differential Duties" (JDE, Oct., 1845) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.35 [1845.10.15] "Economic Sophisms (cont.): IX. An immense Discovery!!!" (JDE, Oct., 1845) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.36 [1845.10.15] "Economic Sophisms (cont.): X. Reciprocity" (JDE, Oct., 1845) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.37 [1845.10.15] "Economic Sophisms (cont.): X. Nominal Prices" (JDE, Oct., 1845) [CW3 - final draft]

-

T.38 [1845.11] Economic Sophisms. First Series (Guillaumin, 1846) [CW3 - final draft]

- 1845.12 ES1 "Author's Introduction"

- 1845.12 ES1.12 "Does Protection increase the Rate of Pay?" [n.d.]

- 1845.12 ES1.13 "Theory and Practice" [n.d.]

- 1845.12 ES1.14 "A Conflict of Principles" [n.d.]

- 1845.12 ES1.15 "More Reciprocity" [n.d.]

- 1845.12 ES1.16 "(Blocked Rivers pleading in favor of the Prohibitionists" [n.d.]

- 1845.12 ES1.17 "A Negative Railway" [n.d.]

- 1845.12 ES1.18 "There are no Absolute Principles" [n.d.]

- 1845.12 ES1.19 "National Independence" [n.d.]

- 1845.12 ES1.20 "Human Labor and Domestic Labor" [n.d.]

- 1845.12 ES1 21 "Raw Materials" [n.d.]

- 1845.12 ES1 22 "Metaphors" [n.d.]

- 1845.11 ES1 "Conclusion" [signed "Mugron, 2 Nov., 1845"]

- T.39 [1845.12.15] "The English Free Trade League and the German League" (JDE, Dec., 1845) [CW6 - to come]

- T.40 [1845.12.15] "A Question submitted to the General Councils of Agriculture, Manufactures, and Commerce" (JDE, Dec., 1845) [CW6 - to come]

Bastiat's Writings in 1846

- T.41 [1846.??] "To M. de Larnac, Deputy of Les Landes, on Parliamentary Reform"

- T.42 Economic Sophisms. Series I. Conclusion is dated "Mugron, 2 Nov., 1845". Published in Paris, by Guillaumin, in Jan. 1846. [CW3 - final draft]

- T.43 (1846.01.15) "Theft by Subsidy" (JDE, Jan. 1846) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.44 (1846.02.08) "Plan for an Anti-Protectionist League" (MB, Feb. 1846) [CW6 - to come]

- T.45 (1846.02.09) "Plan for an Anti-Protectionist League. Second Article" (MB, Feb. 1846) [CW6 - to come]

- T.46 (1846.02.10) "Plan for an Anti-Protectionist League. Third Article" (MB, Feb. 1846) [CW6 - to come]

- T.47 [1846.02.15] "Thoughts on Sharecropping" (15 Feb. 1846, JDE) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.48 (1846.02.18) "The Free Trade Association in Bordeaux" (MB, Feb. 1846) [CW6 - to come]

- T.49 (1846.02.19) "Letter to the Editor of the Journal de Lille, mouth-piece of the northern interests" (MB, Feb. 1846)

- T.50 (1846.02.23) "First Speech given in Bordeaux"

- T.51 [1846.02.26] "The Theory of Profit" (26 Feb. 1846, MB) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.52 (1846.03.08) "To the Editor of the Époque" (MB, March 1846) [CW6 - to come]

- T.53 (1846.03.12) "Free Trade in Action" (MB, March 1846) [CW6 - to come]

- T.54 (1846.04.01) "What is Commerce?" (CF, Apr. 1846) [CW6 - to come]

- T.55 (1846.04.06) "To the Minister of Agriculture and Commerce" (MB, Apr. 1846) [CW6 - to come]

- T.56 (1846.04.11) "To the Editor of the Courrier français" (CF, Apr. 1846) [CW6 - to come]

- T.57 (1846.04.15) "To La Tribune and La Presse on the Question of the Treaty with Belgium" (JDE, Apr. 1846) [CW6 - to come]

- T.58 and T.49 [1846.04] "Two Articles on Postal Reform II" (April 1846, MB) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.60 (1846.05.02) "Commercial Liberty" (MB, May 1846) [CW6 - to come]

- T.61 (1846.05.02) "First Letter to the Editor of the Journal des débats" (JDD, May 1846) [CW6 - to come]

- T.62 (1846.05.10) "Declaration of Principles of the Free Trade Association" [CW6 - to come]

- T.63 (1846.05.14) "Second Letter to the Editor of the Journal des débats" (MB, May 1846) [CW6 - to come]

- T.64 [1846.05.15] "On Competition" (May 1846, JDE) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.65 (1846.05.15) "Salt, the Mail, and the Customs Service" (JDE, May 1846) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.66 [1846.05.19] "On the Railway between Bordeaux and Bayonne" (MB, May 1846)

- T.288 [1846.06??] "A Light-Hearted Look at Free Trade" (mid or late 1846) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.67 (1846.06.14) "To the Members of the Free Trade Association" (MB, June 1846) [CW6 - to come]

- T.68 [1846.06.15] "On the Redistribution of Wealth by M. Vidal" (15 June 1846, JDE) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.69 (1846.06.30) "To M. Tanneguy-Duchâtel, , Minister for the Interior" (MB, June 1846) [CW6 - to come]

- T.70 (1846.07.01) "The Logic of the Moniteur industriel" (MB, July 1846) [CW6 - to come]

- T.71 [1846.07.01] "To the Electors of the District of Saint-Sever" (Mugron, 1 July, 1846)

- T.72 [1846.07.03] "Letter to Roger Dampierre"

- T.73 (1846.08.19) "A Toast offered at the banquet in Honor of Richard Cobden by the Free Traders of Paris" (CF, Aug. 1846) [CW6 - to come]

- T.74 (1846.08.22) "To the Editors of La Presse (1) (CF, Aug. 1846) [CW6 - to come]

- T.75 (1846.08.24) "The Corn Laws and Workers' Wages" (CF, Aug. 1846) [CW6 - to come]

- T.76 (1846.08.29) "Letter to the Moniteur industriel" (CF, Aug. 1846) [CW6 - to come]

- T.77 (1846.09.02) "To the Editors of La Presse (2) (CF, Sept. 1846) [CW6 - to come]

- T.78 (1846.09.18) "To Artisans and Workers" (CF, Sept. 1846) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.79 (1846.09.26) "Second Speech given in the Montesquieu Hall in Paris" (JDE, Oct. 1846) [CW6 - to come]

- T.80 [1846.10.15] "Second Letter to M. de Lamartine (on price controls on food)" (Oct. 1846, JDE) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.81 [1846.10.15] "On Population" (15 Oct. 1846, JDE) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.82 (1846.10.15) "The minutes from a meeting of the Association pour la Liberté des échanges" (JDE, Oct. 1846) [CW4 - to come]

- T.83 (1846.10.22) "To the Merchants of Le Havre (1)" (MB, Oct. 1846) [CW6 - to come]

- T.84 (1846.10.23) "To the Merchants of Le Havre (2)" (MB, Oct. 1846) [CW6 - to come]

- T.85 (1846.10.25) "To the Merchants of Le Havre (3)" (MB, Oct. 1846) [CW6 - to come]

- T.86 (1846.11.10) "To the Editors of Le National (1)" (CF, Nov. 1846) [CW6 - to come]

- T.87 (1846.11.11) "To the Editors of Le National (2)" (CF, Nov. 1846) [CW6 - to come]

- T.88 (1846.12.06) "Post Hoc, Ergo Propter Hoc" (LE, Dec. 1846) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.89 (1846.12.13) "On General Principles" (LE, Dec. 1846) [CW6 - to come]

- T.90 (1846.12.13) "The Right Hand and the Left Hand" (LE, Dec. 1846) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.91 (1846.12.15) "On the Impact of the Protectionist Regime on Agriculture" (JDE, Dec. 1846)

- T.92 (1846.12.20) "Free Trade" (LE, Dec. 1846) [CW6 - to come]

- T.93 (1846.12.27) "What does Invasion amount to?" (LE, Dec. 1846)

- T.94 (1846.12.27) "Recipes for Protectionism" (LE, Dec. 1846) [CW6 - to come] [CW3 - final draft]

Bastiat's Writings in 1847

- T.95 (1847.??) "A Little Manual for Consumers, in other words for Everyone" [CW3 - final draft]

- T.96 (1847.??) "Making a Mountain out of a Mole Hill" [CW3 - final draft]

- T.97 [1847.??] "Anglomania, Anglophobia"

- T.98 (1847.??) "Plan for a Speech on Free Trade to be given in Bayonne" [CW6 - to come]

- T.99 (1847.??) "One Man's gain is another Man's Loss" [CW3 - final draft]

- T.100 (1847.01.03) "Limits which the Free Trade Association imposes" (LE, Jan. 1847) [CW6 - to come]

- T.101 (1847.01.15) "Organisation and Liberty" (JDE, Jan. 1847) [CW6 - to come]

- T.102 (1847.01.17) "The Utopian" (LE, Jan. 1847) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.103 (1847.01.24 ) "The Sliding Scale" (LE, Jan. 1847) [CW6 - to come]

- T.105 [1847.02.21] "To M. de Noailles in the Chamber of Peers (on Perfidious Albion)" (24 Jan. 1847, LE) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.106 (1847.01.31) "Reflections on the year 1846" (LE, Jan. 1847) [CW6 - to come]

- T.107 (1847.01.31) "The Inanity of the Protection of Agriculture" (LE, Jan. 1847) [CW6 - to come]

- T.108 (1847.02.07) "England and Free Trade" (LE, Feb. 1847) [CW6 - to come]

- T.109 (1847.02.07) "Two Principles" (LE, Feb. 1847)

- T.110 (1847.02.14) "Domination through Work" (LE, Feb. 1847)

- T.111 [1847.02.21] "A Curious Economic Phenomenon. Financial Reform in England" (21 Feb. 1847, LE) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.112 (1847.03.07) "The Impact of Free Trade on the Relations between People" (LE, Mar. 1847) [CW6 - to come]

- T.113 (1847.03.14) "The Democratic Party and Free Trade" (LE, Mar. 1847) [CW6 - to come]

- T.114 (1847.03.14) "On the Free Importation of Foreign Cattle" (LE, Mar. 1847) [CW6 - to come]

- T.115 (1847.03.21) "On the Prohibition of Exporting Grain" (LE, Mar. 1847) [CW6 - to come]

- T.116 (1847.03.21) "To increase the price of food is to lower the value of wages" (LE, Mar. 1847) [CW6 - to come]

- T.117 (1847.03.21) "Something Else" (LE, Mar. 1847) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.118 [1847.04.04] "Two Methods of Equalizing Taxes" (4 April 1847, LE) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.119 (1847.04.18 ) "Le National" (LE, Apr. 1847) [CW6 - to come]

- T.120 (1847.04.18) "The World Turned Up-side Down" (LE, Apr. 1847) [CW6 - to come]

- T.121 (1847.04.25) "Programme of the French Free Trade Association" (LE, Apr. 1847) [CW6 - to come]

- T.122 (1847.04.25) "Democracy and Free Trade" (LE, Apr. 1847) [CW6 - to come]

- T.123 (1847.04.25) "The Free Trader's Little Arsensa" (LE, Apr. 1847) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.124 (1847.05.02) "The Sliding Scale and its Impact on England" (LE, May 1847) [CW6 - to come]

- T.125 (1847.05.02) "Mr. Cunin-Gridaine's Logic" (LE, May 1847) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.126 (1847.05.09) "Subsistance Farming" (LE, May 1847) [CW6 - to come]

- T.127 (1847.05.09) "The Emperor of Russia" (LE, May 1847) [CW6 - to come]

- T.128 (1847.05.09) "One Profit against Two Losses" (LE, May 1847) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.129 (1847.05.23) "The People and the Bourgeoisie" (LE, May 1847) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.130 (1847.05.23) "On Moderation" (LE, May 1847) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.131 (1847.05.30) "Two Losses against One Profit" (LE, May 1847) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.132 (1847.05.30) "The Free Trade King" (LE, May 1847) [CW6 - to come]

- T.133 (1847.06.??) "Electoral Sophisms"

- T.134 (1847.06.13) "Speech given in the Duphot Hall" (LE, June 1847) [CW6 - to come]

- T.135 [1847.06.13] "The War against Chairs of Political Economy" (LE, June 1847)

- T.136 [1847.06.20] "The Salt Tax" (20 June 1847, LE) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.137 (1847.06.20) "The Fear of a Word" (LE, June 1847) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.138 (1847.06.20) "Political Economy of the Generals" (LE, June 1847) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.139 [1847.06.27] "Mr. Ewart's Proposal for a Single Tax in England" (27 June, 1847, LE) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.140 (1847.06.27 ) "On Communism" (LE, June 1847) [CW6 - to come]

- T.141 (1847.07.03) "Third Speech given in Paris at the Taranne Hall" [CW6 - to come]

- T.142 (1847.07.11) "Another Reply to La Presse on the Nature of Commerce" (LE, July 1847) [CW6 - to come]

- T.143 [1847.07.11] "On Mignet's Eulogy of M. Charles Comte" (11 July 1847, LE) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.144 (1847.07.25) "High Prices and Low Prices" (LE, July 1847) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.145 (1847.08.??) "Fourth Speech given in Lyon"

- T.146 (1847.08.??) "Fifth Speech given in Lyon" [CW6 - to come]

- T.147 (1847.08.??) "Sixth Speech given in Marseilles" [CW6 - to come]

- T.148 (1847.08.15) "A Letter from M. F. Bastiat: The Three Chief Accusations made by the journal L'Atelier" (JDE, Aug. 1847) [CW6 - to come]

- T.149 [1847.09] "Draft Preface for the Harmonies"

- T.150 (1847.09.05) "A Complaint" (LE, Sept. 1847) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.151 [1847.09.16] "A Letter (to Hippolyte Castille) (on intellectual property)" (9 Sept. 1847, TI) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.152 (1847.09.15) "Minutes of a Public Meeting in Marseilles by the Free Trade Association" (JDE, Sept. 1847) [CW6 - to come]

- T.299 [1847.11??] "The Difference between doing Business and an Act of Charity" (late 1847) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.153 (1847.11.07) "The League's Second Campaign" (LE, Nov. 1847) [CW6 - to come]

- T.154 (1847.11.07) "The Spanish Association for the Defense of National Employment" (LE, Nov. 1847) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.155 (1847.11.14) "A Campaign Strategy proposed to the Free Trade Association" (LE, Nov. 1847) [CW6 - to come]

- T.156 (1847.11.14) "To the Members of the General Council of La Seine" (LE, Nov. 1847) [CW6 - to come]

- T.157 (1847.11.14) "Bastiat's reply to a letter by Blanqui on purely political matters and free trade" (LE, Nov. 1847) [CW6 - to come]

- T.158 (1847.11.21) "To the Members of the General Council of La Niève" (LE, Nov. 1847) [CW6 - to come]

- T.300 [1847.11.28] "On the Difference between Illegal and Immoral Acts" (28 Nov. 1847, LE) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.159 (1847.11.28) "The Specialists" (LE, Nov. 1847) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.160 (1847.12) Le Libre-Échange. Journal de l'Association pour la liberté des échanges. 1er année. 1846-1847. (Paris: Guillaumin and Chaix, 1847).

- T.161 [1847.12.12] "On the Export of Gold Bullion" (12 Dec. 1847, LE) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.162 (1847.12.12) "The Man who asked Embarrassing Questions" (LE, Dec. 1847) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.163 [1847.12.16] "A Speech on intellectual property given to the Publishers Circle" (16 Dec. 1847, TI) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.165 (1847.12.26) "A Letter from Mr. Considérant and a Reply" [CW6 - to come]

- T.166 (1847.12) Articles written for ES2 and not dated (see below for details) [CW3 - final draft]

Bastiat's Writings in Early 1848 (before the Feb. Revolution)

- T.167 [1848.??] "Barataria" (c. 1848) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.168 (1848.??) "Liberty, Equality"

- T.169 (1848.01) Sophismes économiques. Deuxième série. [Completed Dec. 1847, published Jan. 1848] [CW3 - final draft]

- T.170 (1848.01.02) "A Letter from Mr. Considérant and a Reply" (LE, Jan. 1848)

- T.171 (1848.01.01) "Reply to Various Other People" (LE, Jan. 1848) [CW6 - to come]

- T.172 (1848.01.02) "Liberty has given Bread to the English People" (LE, Jan. 1848) [CW6 - to come]

- T.173 (1848.01.07) "Seventh Speech given in Paris in the Montesquieu Hall" [CW6 - to come]

- T.174 (1848.01.16) "Armaments in England" (LE, Jan. 1848) [CW6 - to come]

- T.175 (1848.01.15) "Minutes of the Seventh Meeting of the Free Trade Association" (JDE, Jan. 1848) [CW6 - to come]

- T.176 [1848.01.15] "Natural and Artificial Organisation" (15 Jan., 1848, JDE) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.177 [1848.01.16] "Laziness and Trade Restrictions" (16 Jan. 1848, LE) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.178 [1848.01.22] "Letter to M. Jobard (on intellectual property)" (22 Jan. 1848, Ec. belge) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.179 (1848.01.23) "On Maritime Registration" (LE, Jan. 1848) [CW6 - to come]

- T.180 (1848.01.30) "More on Armaments in England" (LE, Jan. 1848) [CW6 - to come]

- T.181 (1848.02.06) "The Mayor of Énios" (LE, Feb. 1848) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.183 (1848.02.06) "Two Englands" (LE, Feb. 1848) [CW6 - to come]

- T.184 (1848.02.13) "Antediluvian Sugar" (LE, Feb. 1848) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.185 (1848.02.20) "Monita secreta" (LE, Feb. 1848) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.27 [1845.06] Cobden and the League (Guillaumin, 1845). Only the Introduction by Bastiat has been translated. The rest of the book consists of Bastiat's translations and summaries of Anti-Corn Law League speeches and newspaper articles.

- T.38 [1845.11] Economic Sophisms. First Series (Guillaumin, 1846) [also listed as T.42]. Conclusion is dated “Mugron, 2 Nov., 1845". Published in Paris, by Guillaumin, in Jan. 1846.

- T.160 [1847.12] Le Libre-Échange. Journal de l'Association pour la liberté des échanges. 1er année. 1846-1847. (Paris: Guillaumin and Chaix, 1847). This book contains the first year's issues of the journal.

Introduction to Part 2: The “Paris” Writings I: Bastiat and the Free Trade Movement (Oct. 1844 - Feb. 1848)↩

[Updated; 21 June, 2017.]

Trade is a natural right, like property. Every citizen who has created or acquired a product should have the option either of using it immediately or of selling it to someone anywhere in the world who is willing to give him what he wants in exchange. Depriving him of this faculty, when he is not using it for a purpose contrary to public order or morals, and solely to satisfy the convenience of another citizen is to justify plunder and violate the laws of justice.

(Declaration of Principles of the French Free Trade Association, 10 May 1846 (CW6))

Key works from this period:

- the article which first brought him to the attention of the Parisian economists: T.19 "On the Influence of French and English Tariffs on the Future of the Two People", Journal des Économistes, October 1844. (CW6 forthcoming)

- his first book on T.27 Cobden and The League (1845) - in the long “Introduction” Bastiat deals with the strategy adopted by the ACLL and how it might be applied to France (CW6 forthcoming)

- many articles crticising protectionism and subsidies in the Journal des Économistes and the weekly journal of the French Free Trade Association, Le Libre-Échange which would be collected in the two volumes of his economic journalism Economic Sophisms series I (Jan. 1846) and II (Jan. 1848), such as:

- ES1 7 "Petition by the Manufacturers of Candles, etc." (JDE, October 1845), in CW3, pp. 49–53.

- ES1 17 "A Negative Railway" (c. 1845), in CW3, pp. 81–83.

- ES2 11 “The Utopian” (LE, 17 Jan., 1847), in CW3, pp. 187–98.

- ES2 10 “The Tax Collector” (c. 1847), in CW3, pp. 179–87.

- ES3 16 “Making a Mountain Out of a Molehill” (c. 1847), in CW3, pp. 343–50.

- ES3 18 “The Mayor of Énios” (LE, 6 Feb. 1848), in CW3, pp. 355–65.

- a parallel series of articles of a more theoretical nature in which Bastiat develops his innovative ideas which will become his future economic treatise Economic Harmonies

- T.23 “Letter from an Economist to M. de Lamartine” (Feb. 1845, JDE) (CW4 forthcoming)

- T.64 “On Competition” (May 1846, JDE) (CW4 forthcoming)

- T.81 “On Population” (Oct. 1846, JDE) (CW4 forthcoming)

- T.149 “Draft Preface for the Harmonies” (Sept. 1847) CW1, pp. 316–20.

- T.176 “Natural and Artificial Organisation” (Jan., 1848, JDE) (CW4 forthcoming)

- scattered works in which he explores the nature and history of plunder, ES2 1 “The Physiology of Plunder” (late 1847), CW3, pp. 113–30.

Not all the works from this period were written in Paris but they reflect his entry into the orbit of the Guillaumin network[20] of economists and free traders who were based largely in Paris, where he eventually took up residence. (The population of Paris in 1846 was just over 1 million people, thus dwarfing the small world of Mugron from which Bastiat had come). Urbain Guillaumin (1801–1864) was the same age as Bastiat and his publishing firm had become the centre of the political economy movement in Paris. He published most of their books (including nearly all of Bastiat’s), the main journal, the Journal des Économistes (founded 1841), and provided a home for the Political Economy Society (founded 1842) which held monthly meetings which Bastiat attended whenever he could.[21] Most importantly, Guillaumin had developed a network of intellectuals, academics, businessmen, politicians, and journalists which provided Bastiat with important contacts and sources of funding when he came to Paris in May, 1845 when the Political Economy Society hosted a dinner in his honour.[22]

Bastiat’s growing interest in free trade in 1844 led to him doing extensive research on Richard Cobden and the Anti-Corn Law League, which resulted in a long article which was published in the October issue of the Journal des Économistes and material which the following year would be published as a book on Cobden and the League.[23] These two works provided him with the entrée into the Parisian political economy movement which he needed in order to make a career as a free trade activist and then an economist. In the article on “On the Influence of French and English Tariffs” (Oct. 1844) Bastiat explains to French readers some of the profound changes which were sweeping the world as a result of a new climate of opinion in favour of free trade in England which he thinks will also eventually reach France. He wanted to tell them about the activities of the Anti-Corn Law League which the French press had largely ignored, and how free trade is not only an economic issue which will affect the prosperity of all people, but also a political issue in that it was challenging the power and privileges of the industrial and landowning elites which controlled the British government. He predicted something similar would happen in France. In this early article Bastiat shows his typical approach to economic problems which is to combine his solid grasp of economic data with tables of data to back up his arguments, and a strong moral component in which he argues that tariffs and protection are not only economically damaging to ordinary consumers but also violate their rights to liberty and property. The two approaches are tied together with a writing style which is both direct and very engaging.

Cobden and the League (June 1845) was Bastiat’s first book and it was published by Guillaumin which shows how quickly Bastiat was accepted into the free market group in Paris. In the long, nearly 100 page introduction, Bastiat took up a new theme which he had not addressed in his first article, namely, explaining to French readers the ideas and strategies of the Anti-Corn Law League. In his mind the Leaguers had developed an entirely new strategy of peaceful, mass agitation for radical reform from which the French free market movement could learn a great deal. This is why he translated so many of the speeches of the League’s coterie of travelling lecturers as examples for the French to copy. He also pointed out the important role that women played in the behind the scenes organisation of the League, thus demonstrating the depth of support the free trade agitators had been able to acquire since they began operating in 1838. We also see in this piece the beginnings of Bastiat’s interest in the notion of “plunder” (la spoliation) which was to become so important to his thinking over the next couple of years. He would return to this topic in the opening chapter of ES2 on “The Physiology of Plunder” (written late 1847).[24]

In the “Introduction” to Cobden and the League Bastiat linked the policy of tariffs and indirect taxation of consumer goods to the control of the British government by the English aristocracy, or “Oligarchy” as he called them, which had its roots in the Norman Conquest of Britain. These “plunderers” had skewed tax policy so that the burden of taxes was paid by the “industrious class”, the “plundered”, or the ordinary farmers, workers, and shop keepers. By striking at the lynchpin of their power, tariffs, which maintained their incomes at the expence of consumers, the Anti-Corn Law League was striking a blow for democracy and freedom in a “quiet revolution” which would change the entire world. Bastiat took it upon himself at this moment in history to hasten the arrival of this revolution in France by exposing the “sophisms” or the false arguments used by these plunderers to bolster their privileged position in society. The reforms advocated by Bastiat were modeled on those of the Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel, namely to abolish tariffs, to dismantle the colonial system, and to abolish all taxes except for a single, low direct tax like a tariff of 5% or a very low income tax which everyone would pay. [25] The demands he articulated in 1845 remained constant for the rest of his life. Bastiat concluded the introduction with a piece of impassioned rhetoric where he called for “Liberty for all! Free trade with the entire world! Peace with the entire world!”

Over the course of the following three years Bastiat published 21 articles in the JDE (8 in 1845, 10 in 1846, and 3 in 1847),[26] including many academic ones on trade policy and the negative impact of protectionism on France and England, as well as other more popularly written articles which would be included in his collections known as Economic Sophisms (Series I appeared in Jan. 1846, Series II in Jan. 1848).[27] Examples of his more substantial articles on trade policy include, “The Economic Situation of Great Britain: Financial Reforms and Agitation for Commercial Freedom” (June 1845);[28] “On the Future of the Wine Trade between France and England” (Aug. 1845);[29] and “On the Impact of the Protectionist Regime on Agriculture” (Dec. 1846).[30]

No one had ever seen anything like the Economic Sophisms before. In them, Bastiat perfected his “rhetoric of liberty”[31] in defence of free trade and free markets designed for a more popular audience. He used satire, mockery, sarcasm, jokes and puns, fake petitions to government officials, dialogues between stock characters, and sometimes even little plays in which some characters played defenders of tariffs and others their critics.[32] He wrote over 70 of them over a period of three years and produced two published collections (Jan. 1846 and Jan. 1848) which sold very well for Guillaumin and were quickly translated into English and several other European languages. The common aim of these very diverse pieces was to correct commonly held “fallacies” about economics (ideas that were wrong in theory or fact) and to expose and debunk another set of commonly held “sophisms” or partly true and partly false beliefs which were used to advance the private interests of the beneficiaries of tariffs and government privileges. Some of the fallacies he rebutted were the following: that the interests of the producers are the real interest of the nation; real wealth is measured by the amount of labor or effort expended to create goods and services; free trade harms the interests of the nation; and the state can and should provide all the needs of the people. The sophisms Bastiat attacked were very numerous but can be summarised under the following broad categories: “the seen and the unseen” - the idea that one should also look for the hidden or later appearing consequences of any intervention in the economy; positive and negative “ricochet” or flow on effects[33] - this is an early formulation of the Keynesian idea of the “multiplier effect” or that an intervention or subsidy will have a positive flow on effect to others; and the use of euphemisms and frightening language to make one's arguments - that critics of free market talk about trade “wars”, or the market being “flooded” with foreign goods.

Some examples of Bastiat’s best “economic sophisms” are the following. Perhaps his best in the First Series was the “Petition by the Manufacturers of Candles” (Oct. 1845),[34] a fictitious appeal for government assistance by the manufacturers of candles and other forms of artificial light against a foreign competitor, the sun, who undercut their prices and made it hard for them to make a living during daylight hours; and “A Negative Railway” (late 1845)[35] which is a hilarious story based on things Bastiat had observed in his home town when the General Council was debating where stops should be made on the new leg of the Bordeaux to Bayonne railway - the absurdity comes from the fact that if all the vested interests were satisfied the train would be forced to stop an infinite number of times in order to maximise the benefits to each town from overnight stays for passengers en route and the trans-shipping costs of moving luggage and cargo from one train to the next.

In the Second Series, “The Tax Collector” (late 1847)[36] contains a witty dialog between a tax collector, whom Bastiat mockingly calls “Mr. Blockhead”, and a sceptical wine producer, Jacques Bonhomme, who refuses to believe the tax collector’s claims that Jacques’ political “representatives” either represent him in any way or spend his hard earned money wisely in the public interest. In “The Utopian” (Jan. 1847)[37] an unnamed politician (perhaps Bastiat himself) is asked by the King to form a government which has dictatorial powers to enact reforms. The “utopian” politician dreams of all the cuts he could make to government programs and taxation, how many regulations he would abolish, and even how he would abolish the army and replace it with local militias. The story concludes with the utopian politician resigning because he realises his reforms would not work if they were imposed from above on a people who did not believe in their value. This returns to an idea he expressed in the “Introduction” to Cobden and the League that the battle for free trade would be won only after a revolution in thinking had taken place in the minds of voters and consumers.

In the Third Series, which Liberty Fund is publishing for the first time as Bastiat never found the time to publish his own edition before he died, Bastiat uses his stock device of the reductio ad absurdum in “The Mayor of Énios” (Feb. 1848).[38] The Mayor of a small town decides that if tariffs are good for France as a whole then they would also be good for his small town. He makes all the standard arguments in favour of tariffs to the townspeople and persuades them to let him impose tariffs on all goods, French or foreign, which are brought into the town. Trade grinds to a halt for most consumers but not for some privileged local producers within the town. Then the Prefect of the Département summons the mayor to the capital to inform him that only the nation state had the right to impose tariffs and that small towns like his should enjoy the many benefits of free trade and competition with its neighbours. The joke of course is that Bastiat has the Prefect defend free trade on the communal level while at the same time opposing it on the national and international level. In "Making a Mountain out of a Mole Hill" (c. 1847)[39] Bastiat for the first time introduces the figure of Robinson Crusoe[40] shipwrecked on his Island of Despair to explore the nature of individual economic action and choice in its simplest and most abstract form. Bastiat would make much greater use of the Crusoe and Friday “thought experiment” in his treatise Economic Harmonies a couple of years later. This might be the first time any economist has done this and it is doubly noteworthy because it had a profound impact on the Austrian economist Murray N. Rothbard who used Bastiat’s innovation in creating the foundations of his theory of economics in Man, Economy, and State (1962) which he was writing during the 1950s.[41]

For most of 1845–47 Bastiat threw himself whole-heartedly into the French Free Trade movement until his health gave out in early 1848, firstly by writing and perfecting the style of his “economic sophisms” during 1845; helping launch a French Free Trade Association beginning with an Association based in the port city of Bordeaux near where he lived (Feb. 1846) and then a national association in Paris (May 1846); and then founding, editing, and largely writing the Association’s weekly journal Le Libre-Échange in November 1846.[42] The president of the FFTA was the Duc d'Harcourt and Bastiat was the secretary of the Board. Other members of the Board were a “who’s who” of the Parisian economists.

During this period he wrote the “Declaration of Principles” of the FFTA (May 1846)[43], weekly editorials and articles for LE,[44] and crisscrossed the country organising mass meetings at which he and other leading figures in the free trade movement would give speeches. He gave 8 major speeches between Feb. 1846 and Aug. 1847 in Bordeaux, Marseilles, Lyon, and Paris. These will be published in CW6 (forthcoming). The “Declaration of Principles” of the FFTA is an important statement of his belief that free trade was a natural right of individuals just like their right to own property. Although he was not a charismatic public speaking he was very effective with his ability to mix his deep knowledge of the economic data, his skill at satirizing the arguments of his opponents, and his penchant for drawing upon well-known classics of French literature (like the playwright Molière or the writers of fables La Fontaine) to make complex economic ideas understandable to ordinary people. It is quite likely that in his public speeches he entertained the audience with versions of his sophisms which he recited and possibly even acted out for them on the stage. In his journal Libre-Échange, “The People and the Bourgeoisie” (May 1847),[45] he tried to appeal to workers by arguing that they had a property in themselves and their labour which was just as sacred as the property in things so beloved of the bourgeoisie and therefore they should pay no heed to the socialists who were calling for the abolition of property.

There were great hopes during the first year of operation of the Association as the English legislation to repeal the protectionist corn laws made its way through various readings of the bill which finally became law in June 1846. Also, large crowds attended the many public meetings the French free traders held in cities like Bordeaux and Paris at which Bastiat and others spoke. There was even a hint that the French Chamber of Deputies would consider tariff reform but these hopes began to fade in mid–1847 when the Chamber buried any chance for tariff reforms in committee and attendance at the free trade meetings began to fall off. The final blow to the Association came with the outbreak of revolution in February 1848 when the Association’s Board decided to close down the Association as they concluded that socialism posed a greater problem at that moment than tariff policy. By then Bastiat’s health was getting worse and he had to withdraw from the position of editor of Le Libre-Échange.

In addition to his articles on trade policy and his more popular sophisms, Bastiat also wrote articles of a more theoretical nature, some of which would later be included in his treatise Economic Harmonies (1st ed. Jan. 1850, 2nd expanded ed. July 1851). These were on topics such as sharecropping, competition, taxation, population theory, and the nature of economic organisation. It appears that Bastiat already had conceived most of his original and important theoretical ideas before he came to Paris in May 1845 for a welcome dinner hosted by the PES. These were revealed in a very important article he wrote for the JDE in February before he moved to Paris. It was written in the form of a “letter from an Economist” to Alphonse Lamartine,[46] one of the leading literary figures, politicians, and classical liberals of his day, criticising him for his support for the idea that workers had “a right to a job”. It is interesting that at this very moment only a few months after he became known to the Parisian economists he was speaking on their behalf to one of the most eminent men of the period. Some of the important ideas he presented in this article would become very important in his treatise Economic Harmonies and they include the idea that society is a mechanism “(un mécanique sociale) with its own internal ”driving force“ (moteur) which did not require an external ”mechanic“ to make it operate effectively and justly; that there was a providentially guided ”harmony“ of interests which existed in society in the absence of coercion; that there were ”les forces perturbatrices“ (disturbing forces), such as war, government regulations, privileges, subsidies, and tariffs which upset the harmony of the free market; that the free market had within it self-correcting mechanisms which he called ”les forces réparatrices“ (repairing or restorative forces) whereby the market attempts to restore equilibrium after it has been upset by ”les forces perturbatrices“ (disturbing forces); and his first use of the term ”organisation artificielle" (artificial organisation) which would become important in his later critique of socialism.

Another very original and provocative article was the one “On Population” (Oct. 1846)[47] in which he challenged the pessimism of Malthus’s theory by arguing that he had seriously underestimated two things: the productive power of the free market once its shackles had been removed, and the ability and willingness of rational people to plan the size of their families. The article created quite a stir among the economists who did not like the fact that an outsider from the provinces like Bastiat was challenging one of the core beliefs of orthodox political economy. Bastiat’s career as an theoretical economist began in the late fall of 1847 when he was able to give a series of lectures at the Taranne Hall in Paris. His “draft preface” to his lectures[48] gives some idea of how important this was to him, but the lecture series was cut short when revolution broke out at the end of February 1848.

By the end of this period, Bastiat had shown himself to be a gifted economic journalist (perhaps one of the greatest who has ever lived), a successful author, a committed and hardworking free trade activist, and an aspiring economic theorist who had become an important part of the Guillaumin network of economists in Paris.

Endnotes-

Minart discusses the “Guillaumin network” in Gérard Minart, Gustave de Molinari (1819–1912), pour un gouvernement à bon marché dans un milieu libre (Paris: Institut Charles Coquelin, 2012), p. 56. ↩

-

On Guillaumin, see Lucette Levan-Lemesle, "Guillaumin, Éditeur d'Économie politique 1801–1864," Revue d'économie politique, 96e année, No. 2, 1985, pp. 134–149. On the Political Economy Society, see Breton, Yves. "The Société d'économie politique of Paris (1842–1914)." In The Spread of Political Economy and the Professionalisation of Economists: Economic Societies in Europe, America and Japan in the Nineteenth Century, edited by Massimo M. Augello and Marco E. L. Guidi. London: Routledge, 2001. On the JDE, see Lutfalla, Michel. "Aux origines du libéralisme économique en France: Le 'Journal des économistes.'" Revue d'histoire économique et sociale, 50, no. 4, 1972, pp. 494–517. ↩

-

He describes his welcome dinner to Félix Coudroy in Letter 37 to Félix Coudroy, Paris, May 1845, in CW1, pp. 59–61. ↩

-

Bastiat, T.27 Cobden et la Ligue, ou l'agitation anglaise pour la liberté du commerce (Paris: Guillaumin, 1845). The book consisted of Bastiat’s translations and summaries of League speeches and articles from the British press, along with his lengthy introduction, pp. i-xcvi. ↩

-

T.166 “The Physiology of Plunder” (late 1847), ES2 1, CW3, pp. 113–30. ↩

-

See, "Bastiat's Policy on Tariffs" in Further Aspects of Bastiat's Thought, in CW3, p. 455. ↩

-

A full list of the articles Bastiat published in the JDE can be found here (to come). ↩

-

Bastiat, Sophismes économiques. Première série. (Paris: Guillaumin, 1846) and Sophismes économiques. Deuxième série. (Paris: Guillaumin, 1848). He also wrote enough for a Third Series which were not published as a separate volume in his lifetime. All three can be found in CW3 final draft version. FEE ed. of Series I and II only ↩

-

T.28 "Situation économique de la Grande-Bretagne. Réformes financières. Agitation pour la liberté commerciale" (The Economic Situation of Great Britain: Financial Reforms and Agitation for Commercial Freedom), JDE, Juin 1845, T. XI, 233–265. This was adapted from his introduction to his book Cobden and the League, pp. vii ff. ↩

-

T.31 "De l’avenir du commerce des vins entre la France et la Grande-Bretagne" (On the Future of the Wine Trade between France and England), Journal des Économistes, Aug. 1845 in CW6 (forthcoming). ↩

-

T.91 "De l’influence du régime protecteur sur l’agriculture" (On the Impact of the Protectionist Regime on Agriculture), Journal des Économistes, Décembre 1846 in CW6 (forthcoming). ↩

-

See David M. Hart, "Bastiat’s Rhetoric of Liberty: Satire and the 'Sting of Ridicule'," in the Introduction to CW3, pp. lviii-lxiv. ↩

-

See, "The Format of the Economic Sophisms," in the Introduction to CW3, pp. li-lii; and "Bastiat and Conversations about Liberty" in Further Aspects of Bastiat's Thought, in CW3, pp. 470–73. ↩

-

"The Sophism Bastiat never wrote: The Sophism of the Ricochet Effect" in Further Aspects of Bastiat's Thought, in CW3, pp. 457–61. ↩

-

T.33 ES1 7 "Pétition des fabricants de chandelles, etc." (Petition by the Manufacturers of Candles, etc.), Journal des Économistes, October 1845, T. 12, p. 204–07 in CW3, pp. 49–53. FEE ed. ↩

-

T.38 ES1 17 "Un chemin de fer négatif" (A Negative Railway) (c. 1845) in CW3, pp. 81–83. FEE ed. ↩

-

T.166 ES210 "Le percepteur" (The Tax Collector) (c. 1847), in CW3, pp. 179–87. FEE ed. ↩

-

T.102 ES211 "L’utopiste (The Utopian), Libre-Échange, 17 January 1847 in CW3, pp. 187–98. FEE ed. ↩

-

T.181 ES3 18 "Le maire d’Énios" (The Mayor of Énios), Libre-Échange, 6 February 1848, in CW3, pp. 355–65. ↩

-

T.96 ES3 16 "Midi à quatorze heures" (Making a Mountain out of a Mole Hill) (c. 1847) in CW3, pp. 343–50. ↩

-

See "Bastiat’s Invention of 'Crusoe Economics'," in the Introduction to CW3, pp. lxiv-lxvii. ↩

-

Murray N. Rothbard, “6. A Crusoe Social Philosophy,” in The Ethics of Liberty (Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: Humanities Press, 1982), p. 29–34; and Rothbard, Man, Economy and State: A Treatise on Economic Principles, with Power and Market: Government and the Economy. Second Edition. Scholar’s Edition (Auburn, Alabama: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2009), especially Chapter 2. “Direct Exchange”. ↩

-

The first year of the journal was republished in book form by Guillaumin: Le Libre-Échange. Journal de l’Association pour la liberté des échanges. 1er année. 1846–1847. (Paris: Guillaumin and Chaix, 1847). ↩

-

T.62 (1846.05.10) “Declaration of Principles of the Free Trade Association” (Déclaration de principes (Association pour la liberté des échanges)) 10 May, 1846; reprinted in LE 25 Apr. 1847, no. 22, p. 169; along with the Association’s new programme. [OC2.1, pp. 1–4.][CW6] ↩

-

These free trade editorials and articles will appear in CW6 (forthcoming). ↩

-

T.129 ES3 6 "Peuple et Bourgeoisie" (The People and the Bourgeoisie), Libre-Échange, 22 May 1847, in CW3, pp. 281–87. ↩

-

T.23 (1845.01.15) “Letter from an Economist to M. de Lamartine. On the occasion of his article entitled: The Right to a Job ” (Un économiste à M. de Lamartine. A l’occasion de son écrit intitulé: Du Droit au travail ), JDE , February 1845, T. 10, no. 39, pp. 209–223. [OC1.9, pp. 406–28][CW4 forthcoming] ↩

-

T.81 "De la population," (On Population), JDE, 15 Octobre 1846, T. XV, pp. 217–234, in CW4 (forthcoming). A revised version of this article appeared as chapter 16 of the second, expanded edition of Economic Harmonies (1851) which was published after his death. FEE ed. ↩

-

T.149 (Sept. 1847) “Draft Preface for the Harmonies” (Projet de préface pour les Harmonies) in CW1, pp. 316–20. (/titles/2393#lf1573–01_label_689). ↩

Correspondence↩

Letter 32. Mugron, 24 Nov. 1844. To Richard Cobden↩

SourceLetter 32. Mugron, 24 Nov. 1844. To Richard Cobden (OC1, pp. 106-9) [CW1, pp. 50-53].

TextSteeped in the schools of your Adam Smith and our J. B. Say, I was beginning to believe that this doctrine that was so simple and clear had no chance of becoming popular, at least for a long time, since, over here, it is completely [51] stifled by the specious fallacies57 that you refuted so well and which are disseminated by the Fourierist, communist, and other sects with which our country is for the moment infatuated, and also by the disastrous alliance of the party newspapers with those newspapers paid for by committees of manufacturers.

It was in this state of total discouragement in which these sad circumstances had cast me that, as I happened to have taken out a subscription to the Globe and Traveller,58 I learned both of the existence of the League and the struggle between free trade and monopoly in England. As I am an enthusiastic admirer of your powerful and very moral association and in particular of the man who appears to give it such forceful and wise direction in the face of countless difficulties, I have been unable to contemplate this sight without wanting to do something for the noble cause of the liberation of work and commerce. Your honorable secretary, Mr. Hickin, was good enough to send me the issue of the League, dated January 1844, together with a number of documents relating to the campaign.

Equipped with these documents, I have tried to draw public attention to your proceedings, on which French newspapers have maintained a calculated and systematic silence. I have written articles in the newspapers of Bayonne and Bordeaux, two towns naturally positioned to become the cradle of the movement. In addition, recently I had published in Le Journal des économistes (issue no. 35, Paris, October 1844) an article which I recommend to you. What has been the result? Newspapers in Paris, on which our laws confer the monopoly of opinion, have considered discussion to be more dangerous than silence. They have therefore created silence around me, totally sure that these arrangements would reduce me to impotence.

In Bordeaux, I have tried to organize an association for trade liberalization, but I have failed because, although there are a few souls who instinctively would like freedom to a certain extent, there are none who understand it in principle.

What is more, an association functions only through publicity, and it needs money. I am not rich enough to endow it on my own, and asking for money would have created the insurmountable obstacle of suspicion.

I have thought of founding in Paris a daily newspaper based on these two concepts, free trade and the elimination of a partisan spirit. Here again, I [52] have encountered money and other problems, which I will not go into. I will regret it for the rest of my life, because I am convinced that a newspaper like this, which fills a public need, would have a chance of success. (I have not given up on this.)

Lastly, I wanted to know whether I had any chance of being elected a deputy, and I have become certain that my fellow citizens would give me their vote, since I almost achieved a majority at the last elections. However, personal considerations prevent me from aspiring to this position, which I might have used to the advantage of our cause.

Obliged to limit my action, I began to translate your sessions59 in Drury Lane and Covent Garden. Next May, I will submit this translation for publication. I expect it to have a good effect.

- 1. It will be necessary for France to become acquainted with the existence of the spirited campaign in England against monopolies.

- 2. It will be necessary for people to stop thinking that freedom is just a trap set by England for other nations.

- 3. The arguments in favor of free trade would perhaps have more effect if they were in the lively, varied, and popular form of your speeches rather than in the methodical works of economists.60

- 4. Your tactic that is so well directed downward to the people and upward to Parliament will teach us to act in the same way and inform us on the benefit we may gain from constitutional institutions.

- 5. This publication will be a forceful blow to the two major plagues of our time, the partisan spirit and national hatreds.

- 6. France will see that in England there are two entirely conflicting opinions and that, consequently, it is absurd and contradictory to envelop the whole of England in the same hatred.

In order for this work to be complete, I would have liked to obtain a few documents on the origin and beginnings of the League. A short history of this association would be a suitable preface to the translation of your speeches.61 I have asked Mr. Hickin for these documents, but doubtless he has been too [53] busy to reply to me. My documents go back only to January 1843; I would at least need the debate in Parliament on the 1842 tariff and in particular the speech in which Mr. Peel proclaimed the economic truth in the form that has become so popular, “We must be allowed to buy in the cheapest market, etc.”

I would also like you to tell me which of your speeches, either at meetings or in Parliament, you think most appropriate to translate. Lastly, I would like my book to contain one or two free-trade discussions in the House of Commons and ask that you would be good enough to tell me which ones.

I would be most honored to receive a letter from the man of our time for whom I have the keenest and most sincere admiration.

Letter 33. Mugron, 24 Nov. 1844. To Horace Say↩

SourceLetter 33. Mugron, 24 Nov. 1844. To Horace Say (OC7, pp. 377-80) [CW1, pp. 53-55].

TextPlease allow me to express to you the feeling of deep satisfaction I had on reading your kind letter of the 19th of this month. Without the sentiments contained in this most valued letter, how would we, men of solitude who are deprived of the useful warnings received through contact with the rest of the world, know whether or not we are in the group of dreamers, all too common in the country, who have allowed themselves to be obsessed by a single idea? Do not tell me, sir, that your approval can merely have limited value in my eyes. Since France and humanity lost your illustrious father, whom I also venerate as my intellectual father, what sentiments can be more precious to me than yours, especially when your own writings and the expressions of confidence which the population of Paris have heaped on you give such authority to your judgments?

Among the authors of your father’s school whom death has respected, there is one above all whose agreement is of inestimable value to me, although I would not have dared to solicit it. I refer to M. Charles Dunoyer. His first two articles in Le Censeur européen (“On the Equilibrium Between Nations”),62 together with those by M. Comte which precede them,63 settled [54] the direction of my thought and even my political actions a long time ago.64 Since then the economist school65 appears to have given way before the host of socialist sects which seek to achieve the universal good, not in the laws of human nature but in artificial organizations which are the products of their imagination. This is a disastrous mistake, which M. Dunoyer has been campaigning against for a long time with a perseverance that can almost be called prophetic. I therefore could not prevent the rise of a feeling almost of pride when I learned from your letter that M. Dunoyer has approved of the spirit of the text you have had the goodness to include in your esteemed collection.

You are kind enough, sir, to encourage me to send you a further text. I am now devoting the little time I have at my disposal to a work of patience, the usefulness of which I consider to be unquestionable, even though it consists only of simple translations. In England there is a major movement in support of free trade. This movement has been kept carefully hidden by our newspapers and where, from time to time, they are obliged to mention it, it is to distort its nature and influence. I would like to put documents relating to it before the French public and show that on the other side of the Channel there is a party with many members that is powerful, honest, judicious, ready to become the national party, and ready to direct the policy of England, and it is to this party that we should extend a hand of friendship. The public would then be capable of judging whether it is reasonable to envelop the whole of England in the wild hatred that the press is trying to whip up with such obstinacy and success.

I am expecting other benefits from this publication. Readers will find in it an attack on the very root of the partisan spirit, the undermining of the basis of national hatred, the theory of markets set out not methodically but using forms that are popular and striking, and finally, they will see in action the energy, the demonstration tactics which now mean that in England, when genuine abuse is attacked, it is possible to forecast the day it will be [55] abolished, just as our military engineers forecast the time at which besiegers will seize a citadel.

I am planning to come to Paris in April next to supervise the printing of this publication,66 and if I had any hesitations in doing this your kind offer and the desire to make your acquaintance and those of the distinguished men whom you meet would be enough to persuade me.

Your colleague, M. Dupérier, was also good enough to write to me about my article. “It is good in theory,” he said; and I am tempted to reply to him by your esteemed father’s quip, “My God, what is no good in practice is good for nothing.” M. Dupérier and I follow very different paths in politics. My esteem for him is all the higher for his frankness and the frankness of his letter. These days, there are very few candidates who tell their opponents what they think.

I forgot to say that if the time and my health permit, following your encouraging invitation I will send another article to Le Journal des économistes.67

I would be grateful, sir, if you would convey to MM Dussard, Fix, and Blanqui my thanks for their kindness and assure them that I wholeheartedly support their noble and useful work.

P.S. I am taking the liberty of sending you a text published in 1842 relating to the elections written by one of my friends, M. Félix Coudroy. You will see that the doctrines of MM Say, Comte, and Dunoyer have generated some green shoots in places on the arid soil of the Landes. I thought you would be pleased to learn that the sacred fire is not quite extinguished. As long as there is still a spark, we should not lose hope.

Letter 216 to Félix Coudroy (1845)↩

SourceLetter 216: Letter to Félix Coudroy (1845). This letter was discovered by the original French editor Paillottet among Bastiat's papers and was inserted in a footnote to T.9 "Reflections on the Question of Dueling" (11 February 1838) which was a review in the local newspaper La Chalosse of Coudroy's pamphlet on dueling. Paillottet states it was written sometime in 1845. [OC7, p. 10] [CW1, p. 309].

Editor's IntroductionThis short letter to his boyhood friend and neighbour in Mugron Félix Coudroy 47 tells us something about Bastiat's method of writing, namely that he preferred the simplicity and directness of his first drafts. It also shows us that he was aware of a new work by one of the leading members of the circle of economists in Paris, Charles Dunoyer, 48 whose three-volume magnum opus De la liberté du travail had been published in early 1845. Dunoyer was the President of the Political Economy Society which would host a welcome dinner for Bastiat in Paris in May 1845. Coudroy and Bastiat belonged to a discussion group in Mugron called "The Academy" which would meet regularly to discuss new books and current events and where they no doubt discussed Dunoyer's book soon after it appeared. Bastiat would write but not publish a review of Dunoyer's book in March 1845 which can be found below T.20 "On the Book by M. Dunoyer. On The Liberty of Working" (March, 1845). Coudroy would later that year write a long review of Bastiat's first book on Cobden and the League for the JDE. 49

TextMy dear Félix,

Because of the difficulty of reading, I cannot properly judge the style, but my sincere conviction (you know that here I set aside the usual modesty) is that our styles have different qualities and faults. I believe that the qualities of yours are such that, when it is used, it shows genuine talent; I mean to say a style that is lively and animated with general ideas and glimpses that are luminous. Always make copies on small sheets; if one needs to be changed, it will not cause much trouble. When you are copying you will perhaps be able to add polish, but, for my part, I note that the first draft is always faster and more accessible to today's readers who scarcely go into anything in depth.

Do you not have an opinion of M. Dunoyer?

47 Félix Coudroy (1801-74) was the son of a doctor from Mugron and was a boyhood friend and eventually a neighbour of Bastiat's in Mugron. He studied law in Toulouse and Paris but a long illness prevented him from practicing. Coudroy and Bastiat were both members of a local discussion group in Mugron, "The Academy," where they pursued their intellectual interests for over 20 years.

48 Charles Dunoyer (1786-1862) was a journalist; an academic (a professor of political economy); a politician; the author of numerous works on politics, political economy, and history; a founding member of the PES (1842) of which he was the permanent president; and a key figure in the French classical liberal movement of the first half of the nineteenth century.

49 Félix Coudroy, "De l'influence de l'esprit et des procédés de la Ligue sur les progrès de la civilisation," JDE, T. 12, N° 48, Novembre 1845, pp. 349-368.

Letter 34. Mugron, 7 March 1845. To M. Ch. Dunoyer↩

SourceLetter 34. Mugron, 7 March 1845. To M. Ch. Dunoyer, membre de l'Institut (OC7, pp. 371-72) [CW1, pp. 55-56].

TextOf all the testimonials I might have hoped to receive, that which I have just received from you is certainly the most precious. Even allowing for kindness [56] in the very flattering references to me on the first page of your book,69 I cannot help being certain that I have your vote, knowing how much you are in the habit of matching your utterances to your thought.

When I was very young, sir, a happy chance made me pick up Le Censeur européen and I owe the direction of my studies and outlook to this circumstance. In the time that has elapsed since this period, I am unable to distinguish what is the fruit of my own meditations from what I owe to your writings, so completely do they appear to have been assimilated. But if all that you had done were to reveal to me in society and its virtues (its views, ideas, prejudices, and external circumstances) the true elements of the good it enjoys and the evils it endures, if all you had taught me were to see in governments and their forms only the results of the physical and moral state of society itself, it would be none the less proper, whatever additional knowledge I had managed to acquire since then, to give you and your colleagues the credit for its direction and principle. It is enough to say to you, sir, that nothing could give me more genuine satisfaction than the reception you have given to the two articles I sent to Le Journal des économistes and the sensitive way in which you were kind enough to express it.70 I will be devoting serious study to your book and gleaning much enjoyment from following the development of the fundamental distinction to which I have just referred.

Letter 35. Mugron, 7 March 1845. To M. Al. de Lamartine↩

SourceLetter 35. Mugron, 7 March 1845. To M. Al. de Lamartine. (OC7, pp. 373-74) [CW1, pp. 56-57].

TextAbsence has prevented me from expressing to you earlier the deep gratitude I felt at the reception you deigned to give to the letter I took the liberty of addressing to you through Le Journal des économistes. The letter you have [57] been good enough to write to me is very precious to me and I will always keep it, not only because of the inimitable charm which pervades it but also and above all as an example of your kind readiness to encourage the first attempts of a novice who has not been afraid to point out in your admirable writings a few proposals which he considers to be errors that have escaped your genius.

Perhaps I have gone too far in asking you for that analytical rigor, that accuracy in dissection which explores the field of discovery but which cannot enlarge it. All human faculties have their mission; it is up to a genius to lift himself up to view new horizons and point them out to the crowd. At first these horizons are vague, and reality and illusion are confused in them; the role of analysts is then to come and measure, weigh, and distinguish them. This is how Columbus revealed a new world. Do we find out whether he had taken all the measurements and traced all the contours? Is it even important that he thought he had landed in Cathay? Others have come after, patient workers who have corrected and added to the work. Their names remain unknown while that of Columbus has resounded down the centuries. But, sir, is not a genius the king of the future rather than of the present? Can he claim immediate and practical influence? Do his powerful leaps forward into unknown regions have much in common with the activities of men of the present time or those of businessmen? This is a doubt that I am putting to you; your future will answer it.

You are good enough to acknowledge, sir, that I have traveled through the domain of liberty and you are urging me to rise to meet equality and still further to meet fraternity. How can I help but try, when the request is yours, to take new steps in this noble direction? Doubtless, I will not attain the heights to which you soar, since the habits of my mind no longer allow me to use the wings of imagination. But I will endeavor at least to direct the torch of analysis to a few corners of the huge subject you are suggesting that I study.

Permit me to end by saying, sir, that a few incidental disagreements do not prevent me from being the most sincere and fervent of your admirers, as I hope one day to be the most fervent of your disciples.

Letter 36. Mugron, 8 Apr. 1845. To Richard Cobden↩

SourceLetter 36. Mugron, 8 Apr. 1845. To Richard Cobden (OC1, pp. 109-10) [CW1, p. 58].

TextSince you permit me to write to you, I will reply to your kind letter dated 12th December last. I have been discussing the printing of the translation I told you about with M. Guillaumin, a bookseller in Paris.

The book is entitled Cobden and the League, or the Campaign in England in Favor of Free Trade. I have taken the liberty of using your name for the following reasons: I could not entitle this work The Anti-Corn Law League. Apart from the fact that this would have a barbarous sound for French ears, it would have brought to mind just a limited conception of the project. It would have presented the question as purely English, whereas it is a humanitarian one, the most notably so of all those which have brought campaigning to our century. A simpler title, The League, would have been too vague and would have made people think of an episode in our national history. I therefore felt it necessary to make it clear by preceding it with the name of the person acknowledged to be the “driving force of this campaigning.” You have yourself recognized that individual names were sometimes needed “to give point, to direct attention” and I am using this as my justification.

Fashion—individual names, acknowledged reputations—has so much influence here that I felt it necessary to make a further effort to bring it over to our side. I have written a letter to M. de Lamartine in the économistes (the February 1845 issue).72 This illustrious writer, yielding to the tyrant fashion, had assailed economists in the most unjust and thoughtless manner, since, in the same text, he adopted their principles. I have reason to believe, from the reply he was good enough to send me, that he is not far from joining our ranks, and that would perhaps be enough to cause an unexpected swing in public opinion to us. Doubtless, such a swing would be fragile, but finally we would have, at least temporarily, an audience, and that is what we lack. For my part, I ask for one thing only, and that is that people do not deliberately cover their ears.

Permit me to recommend that you peruse the letter to which I refer, if you have the opportunity.

Letter 37. Paris, May 1845. To Félix Coudroy↩

SourceLetter 37. Paris, May 1845. To Félix Coudroy (OC1, pp. 50-52) [CW1, pp. 59-61].

TextMy dear Félix, I am sure that you are waiting to hear from me. I, too, have a lot to tell you but I must be brief. Although at the end of each day it transpires that I have done nothing, I am always busy. In Paris, the way things are, until you are in the swing of things you need half a day to put fifteen minutes to good use.