The Collected Economic Sophisms of Bastiat

The Collected Economic Sophisms of Frédéric Bastiat

[Created: Nov. 16, 2015]

|

|

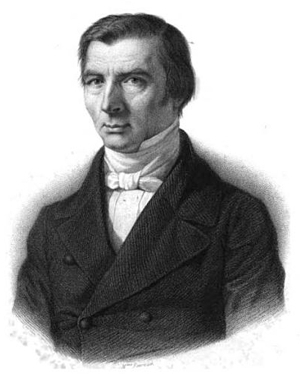

Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850) |

Title Page of the Second Series of Economic Sophisms (1848) |

For more information about Frédéric Bastiat see the following:

- Summary of the Bastiat Project

- Works in the OLL by Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850)

- A Reader’s Guide to the Works of Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850)

- A Chronological List of Bastiat’s Writings

-

The Collected Works of Frédéric Bastiat. In Six Volumes (Indianapolis:

Liberty Fund, 2011 -2015), General Editor Jacques de Guenin. Academic Editor

Dr. David M. Hart. Books.

- Vol. 1: The Man and the Statesman. The Correspondence and Articles on Politics (March 2011)

- Vol. 2: “The Law,” “The State,” and Other Political Writings, 1843-1850 (June 2012)

- Vol. 3: Economic Sophisms and “What is Seen and What is Not Seen” (in production)

- Vol. 4: Miscellaneous Works on Economics: From Jacques-Bonhomme to Le Journal des Économistes (forthcoming)

- Vol. 5: Economic Harmonies (forthcoming)

- Vol. 6: The Struggle Against Protectionism: The English and French Free-Trade Movements (forthcoming)

Introduction to the Sophisms

[The following in an exerpt from David Hart's Introduction to volume 3 of The Collected Works of Frédéric Bastiat (forthcoming) which will contain the Complete Economic Sophisms as well as What is Seen and What is Not Seen. There are references in the text to material which is not in this file, such as Glossaries and Appendices, but which will be in the printed version of the book.]

"It has sometimes happened that I have combated privilege by making fun of it. I think this was quite excusable. When a few people wish to live at the expense of all, it is totally permissible to inflict the sting of ridicule on the minority that exploits and the majority that is exploited." [ES3 12, “Disastrous Illusions,” pp. 000-00, in this volume.]

It is an interesting question to ask oneself where Bastiat got the idea of writing short, pithy essays for a popular audience in which he debunked the misconceptions (“sophisms” or “fallacies”) people had about the operations of the free market in general and of free trade in particular. If refuting fallacies was his end, then the use of constructed conversations between two idealised representatives of conflicting points of view was often the means to that end.

For Bastiat, these articles were short essays written for a general audience which attempted to debunk a commonly held misperception or misunderstanding of an economic point of view. The essay would be written in a familiar style, often in the form of a dialog between two individuals who held opposing views. Or, it would be a satirical “petition” to the government or king requesting some obviously absurd law to “protect” their industry from competition. In the nineteenth century translators of Bastiat’s Sophisms used the word “fallacies,” which is somewhat misleading as there is a difference between the two. A sophism is something which is partly true and which is used as a specious argument designed to mislead the pubic in order to benefit some vested political or economic interest. A fallacy is a clearly mistaken belief based upon faulty reasoning or incorrect assumptions. Bastiat sometimes goes from one to the another in his writings but he has a clear distinction in mind between intellectual error (“the fallacy”) and the rhetorical purposes to which partial truth and partial error can be used in arguments over government policies (“the sophism”).

Bastiat’s goals in organizing a French free trade movement, engaging in popular economic journalism, and standing for election can be summarized as follows: to expose the bad effects of government intervention in the economy; to uproot preconceived and incorrect economic ideas; to arouse a sense of injustice at the immoral actions of the government and its favoured elites; to create “justified mistrust among the oppressed masses” of the beneficiaries of government privilege; and to open the eyes and stiffen the resistance of “the dupes” of government policies. The problem he faced was to discover the best way to achieve this for a popular audience who was gullible about the government’s professed motives in regulating the economy and who were largely ignorant of economic theory.

A major problem Bastiat is acutely aware of is that political economy had a justified reputation for being “dry and dull,” and it was this reputation that Bastiat wanted to overcome with the style he adopted in the Sophisms. The issue was how to be appealing to popular readers whom he believed had become “the dupes” of those benefitting from the system of legal plunder. The means Bastiat adopted to achieve his political goals was to write in a style which ordinary people would find appealing, amusing, and convincing and an analysis of the devices he used in composing his Sophisms reveals the great efforts Bastiat took in trying to do this.

The style and the rhetorical devices Bastiat used in the individual sophisms show considerable variety and skill in their construction. Bastiat has been justly recognized for his excellent style by economists such as Friedrich Hayek and the historian of economic thought Joseph Schumpeter, but this has not been studied in any detail. Schumpeter described Bastiat in very mixed terms as a brilliant economic journalist but as “no theorist” at all:

Admired by sympathizers, reviled by opponents, his name might have gone down to posterity as the most brilliant economic journalist who ever lived... I do not hold that Bastiat was a bad theorist. I hold that he was no theorist.(Schumpeter, History of Economic Analysis, p. 500.)

Friedrich Hayek seems to agree with Schumpeter that Bastiat was not a major theorist but that he was “a publicist of genius” who did pioneering work in exposing economic fallacies held by the general public. [Hayek, “Introduction,” [Bastiat], Selected Essays on Political Economy, p. ix.] Nevertheless, Schumpeter did acknowledge a key aspect of Bastiat’s style noting that “(a) series of Sophismes économiques followed, whose pleasant wit... has ever since been the delight of many.”

A list of the rhetorical devices used by Bastiat in the Sophisms shows the breadth and complexity of what one might call his “rhetoric of liberty,” which he formulated to expose the follies of the policies of the ruling elite and their system of “legal plunder,” and to undermine their authority and legitimacy with “the sting of ridicule”:

- a standard prose format which one would normally encounter in a newspaper

- the single authorial voice in the form of a personal conversation with the reader

- a serious constructed dialogue between stock figures who represented different viewpoints (in this Bastiat was influenced by Jane Marcet and Harriet Martineau; Gustave de Molinari continued Bastiat’s format in some of his writings in the late 1840s and 1850s)

- satirical “official” letters or petitions to government officials or ministers, and other fabricated documents written by Bastiat (in these Bastiat would usually use a reductio ad absurdum argument to mock his opponents’ arguments)

- the use of Robinson Crusoe “thought experiments” to make serious economic points or arguments in a more easily understandable format

- “economic tales” modelled on classic French authors such as La Fontaine’s fables, and Andrieux’s short stories

- parodies of well-known scenes from French literature, such as Molière’s plays

- quoting scenes of plays were the playwright mocks the pretensions of aspiring bourgeois who want to act like the nobles who disdain commerce (e.g., Moliere, Beaumarchais)

- quoting poems with political content, e.g. Horace’s Ode on the transience

of tyrants

- quoting satirical songs about the foolish or criminal behaviour of kings or emperors (such as Napoleon) (Bastiat seems to be familiar with the world of the “goguettiers” (political song writers, especially Béranger) and their interesting sociological world of drinking and singing clubs

- the use of jokes and puns (such as the names he gave to characters in his dialogs (Mr. Blockhead), or place names (Stulta and Puera), and puns on words such as Highville, and gaucherie)

Our study of Bastiat’s Sophisms reveals a well read man who was familiar with classic French literature, contemporary songs and poems, and opera. The sheer number and range of material which Bastiat was able to draw upon in his writings is very impressive. It not only includes the classics of political economy in the French, Spanish, Italian, and English languages but also a very wide collection of modern French literature which includes the following: fables and fairy tales by La Fontaine and Perrault; plays by Molière, Beaumarchais, Victor Hugo, Regnard, Désaugiers, Collin d’Harleville; songs and poems by Béranger and Depraux, short stories by Andrieux, odes by Horace, operas by Rossini, poems by Boileau-Despréaux and Viennet, and satires by Courier de Méré. The plays of Molière were Bastiat’s favourite literary source to quote and he used Tartuffe, or the Imposter (1664), The Misanthrope (1666), L’Avare (The Miser) (1668), Le Bourgeois gentihomme (The Would-Be Gentleman) (1670), and Le malade imaginaire (The Imaginary Invalid, or the Hypocondriac) (1673).

Bastiat also wrote what might be called “political sophisms” in order to debunk fallacies of a political nature, especially concerning electoral politics and the ability of political leaders to initiate fundamental reforms. He had hinted in the Conclusion to ES1 that he had more in mind than the debunking of just economic sophisms. He explicitly mentions four specific types of sophistry which concerned him, namely theocratic, economic, political, and financial sophistry. Bastiat devoted most of his efforts to exposing economic sophisms, mentioning theocratic and financial sophisms only in passing if at all. He did however write a number of political sophisms which will be briefly discussed here.

The “economic” and “political” sophisms are closely related in Bastiat’s mind because the advocates of protectionism were only able to get special privileges because they controlled the Chamber of Deputies and the various Councils which advised the government on economic policy. Bastiat wrote five sophisms which can be categorized as political sophisms. One he explicitly called “Electoral Sophisms” (undated but probably written during 1847) which is a Benthamite listing of the kinds of false arguments people give for why they might prefer voting for one candidate over another. Another is called “The Elections” (also written sometime in 1847) and is a dialog between a “countryman” (a farmer) who argues with a political writer, a parish priest, and an electoral candidate.

Two of the sophisms which appear in this volume, although they deal with significant economic issues, also deal with political matters which qualify them to be regarded as political sophisms. “The Tax Collector” (ES2 10, c.1847) is a discussion between Jacques Bonhomme and a tax collector, wickedly called “Mr. Blockhead”, where an amusing and somewhat convoluted discussion about the nature of political representation takes place. Bonhomme is merely confused by the trickery of the tax collector’s euphemisms about how the elected deputies in the Chamber are his true representatives. The second is “The Utopian” (ES2 11 , Jan. 1847) where Bastiat discusses the problems faced by a free market reform-minded Minister who is unexpectedly put in charge of the country by the King. There is so much the utopian reformer wants to do but the dilemmas and ultimate failure of top-down political and economic reform are exposed by Bastiat.

The fifth essay which might also be regarded as a political sophism is his famous essay “The State” which appeared initially as a draft in the magazine Jacques Bonhomme (June 11-15, 1848) and then in a longer form in the Journal des Débats (September 1848). Here he attempts to rebut the folly of the idea which was widespread during the first few months following the February Revolution that the state could and should take care of all the needs of the people by taxing everybody and giving benefits to everybody.

Economic Sophisms and the other writings in this volume show Bastiat at his creative and journalistic best: his skill at mixing serious and amusing ways of making his arguments is unsurpassed; the quality of his insights into profound economic issues are often exceptional and sometimes well ahead of his time; his ability to combine his political lobbying for the Free Trade Movement, his journalism, his political activities during the 1848 Revolution, and his scholarly activities is most unusual; and his humor, wit, and literary knowledge which he scatters throughout his writings demonstrate that he deserves his reputation as one of the most gifted writers on economic matters who still deserves our close attention today.

Table of Contents

Economic Sophisms. Series I [December 1845]

- [Author’s Introduction to Economic Sophisms]

- I. Abundance and Scarcity [April 1845]

- II. Obstacle and Cause [April 1845]

- III. Effort and Result [April 1845]

- IV. Equalizing the Conditions of Production [July 1845]

- V. Our Products are weighed down with Taxes [July 1845]

- VI. The Balance of Trade [October 1845]

- VII. Petition by the Manufacturers of Candles, etc. [October 1845]

- VIII. Differential Duties [October 1845]

- IX. An immense Discovery!!! [October 1845]

- X. Reciprocity [October 1845]

- XI. Nominal Prices [October 1845]

- XII. Does Protection increase the Rate of Pay? [n.d.]

- XIII. Theory and Practice [n.d.]

- XIV. A Conflict of Principles [n.d.]

- XV. More Reciprocity [n.d.]

- XVI. Blocked Rivers pleading in favor of the Prohibitionists [n.d.]

- XVII A Negative Railway [n.d.]

- XVIII There are no Absolute Principles [n.d.]

- XIX. National Independence [n.d.]

- XX. Human Labor and Domestic Labor [n.d.]

- XXI. Raw Materials [n.d.]

- XXII. Metaphors [n.d.]

- Conclusion

Economic Sophisms. Series II [January 1848]

- I. The Physiology of Plunder [n.d.]

- II. Two Moral Philosophies [n.d.]

- III. The Two Axes [n.d.]

- IV. The Lower Council of Labor [n.d.]

- V. High Prices and Low Prices [25 July 1847]

- VI. To Artisans and Workers [18 September 1846]

- VII. A Chinese Tale [n.d.]

- VIII. Post Hoc, Ergo Propter Hoc [6 December 1846]

- IX. Theft by Subsidy [January 1846]

- X. The Tax Collector [n.d.]

- XI. The Utopian [17 January 1847]

- XII. Salt, the Mail, and the Customs Service [May 1846]

- XIII. Protection, or the Three Municipal Magistrates [n.d.]

- XIV. Something Else [21 March 1847]

- XV. The Free Trader’s Little Arsenal [26 April 1847]

- XVI. The Right Hand and the Left Hand [13 December 1846]

- XVII. Domination through Work [14 February 1847]

Economic Sophisms. Series III. [Dec. 1846 - Mar. 1848]

- I. Recipes for Protectionism [27 December 1846]

- II. Two Principles [7 February 1847]

- III. M. Cunin-Gridaine’s Logic [2 May 1847]

- IV. One Profit versus Two Losses [9 May 1847]

- V. On Moderation [22 May 1847]

- VI. The People and the Bourgeoisie [22 May 1847]

- VII. Two Losses versus One Profit [30 May 1847]

- VIII. The Political Economy of the Generals [20 June 1847]

- IX. A Protest [30 August 1847]

- X. The Spanish Association for the Defense of National Employment and the Bidassoa Bridge [7 November 1847]

- XI. The Specialists [28 November 1847]

- XII. The Man who asked Embarrassing Questions [12 December 1847]

- XIII. The Fear of a Word [June 1847]

- XIV. Anglomania, Anglophobia [c. 1847]

- XV. One Man’s gain is another Man’s loss [c. 1847)

- XVI. Making a Mountain out of a Mole Hill [c. 1847]

- XVII. A Little Manual for Consumers, in other words for Everyone [c. 1847]

- XVIII. The Mayor of Énios [6 February 1848]

- XIX. Antediluvian Sugar [13 February 1848]

- XX. Monita Secreta: The Secret Book of Instructions [20 February 1848]

- XXI. The Immediate Relief of the People [12 March 1848]

- XXII. A Disastrous Remedy [12 March 1848]

- XXIII. Circulars from a Government that is Nowhere to be Found [19 March 1848]

- XXIV. Disastrous Illusions [March 1848]

1. Economic Sophisms. Series I1 [December 1845]

Publishing History2↩

The First Series of Economic Sophisms (henceforth abbreviated as ES1) was completed in November 1845 (Bastiat signed the conclusion “Mugron, 2 November, 1845”) and was probably printed in late 1845 or early 1846. The Bibliothèque nationale de France does not show an edition published in 1845 but there are two listed for 1846, one of which is called the second edition. Presumably the other is the true first edition which appeared in early (possibly January) 1846.3

The first eleven chapters (of an eventual twenty two) of this "first series" of economic sophisms had originally appeared as a series of three articles in the Journal des économistes in April, July, and October 1845 under the name of “Sophismes économiques”.4 If chapters twelve to twenty two were also published elsewhere the place and date of original publication was not given by Paillottet:

- [No title given] [1st published in book], OC, vol. 4, pp. 1-5.

- I. “Abondance, disette” (Abundance and Scarcity) [JDE, April 1845, T. 11, p. 1-8]. OC, vol. 4, pp. 5-14.

- II. “Obstacle, cause” (Obstacle and Cause] [JDE, April 1845, T. 11, p. 8-10]. OC, vol. 4, pp. 15-18.

- III. “Effort, résultat” (Effort and Result) [JDE, April 1845, T. 11, p. 10-16]. OC, vol. 4, pp. 19-27.

- IV. “Égaliser les conditions de production” (Equalizing the Conditions of Production) [JDE, July 1845, T. 11, p. 345-56]. OC, vol. 4, pp. 27-45.

- V. “Nos produits sont grevés de taxes” (Our Products are weighed down with Taxes) [JDE, July 1845, T. 11, p. 356-60]. OC, vol. 4, pp. 46-52.

- VI. “Balance du commerce” (The Balance of Trade) [JDE, October 1845, T. 12, p. 201-04]. OC, vol. 4, pp. 52-57.

- VII. “Pétition des fabricants de chandelles, etc.” (Petition by the Manufacturers of Candles, etc.) [JDE, October 1845, T. 12, p. 204-07]. OC, vol. 4, pp. 57-62.

- VIII. “Droits différentiels” (Differential Duties) [JDE, October 1845, T. 12, p. 207-08]. OC, vol. 4, pp. 62-63.

- IX. “Immense découverte!!!” (An immense Discovery!!!) [JDE, October 1845, T. 12, p. 208-11]. OC, vol. 4, pp. 63-67.

- X. “Réciprocité” (Reciprocity) [JDE, October 1845, T. 12, p. 211]. OC, vol. 4, pp. 67-70.

- XI. “Prix absolus” (Nominal Prices) [JDE, October 1845, T. 12, p. 213-15 (this chapter was originally numbered XII in the JDE but became chapter 11 in the book version of Economic Sophisms and incorporated chapter XI. “Stulta et Puera”, from the JDE version p. 211-12)]. OC, vol. 4, pp. 70-74.

- XII. “La protection élève-t-elle le taux des salaires?” (Does Protection increase the Rate of Pay?) [no date given] [1st published in book]. OC, vol. 4, pp. 74-79.

- XIII. “Théorie, Pratique” (Theory and Practice) [no date given] [1st published in book]. OC, vol. 4, pp. 79-86.

- XIV. “Conflit de principes” (A Conflict of Principles) [no date given] [1st published in book]. OC, vol. 4, pp. 86-90.

- XV. “Encore la réciprocité” (More Reciprocity) [no date given] [1st published in book]. OC, vol. 4, pp. 90-92.

- XVI. “Les fleuves obstrués plaidant pour les prohibitionistes” (Blocked Rivers pleading in favor of the Prohibitionists) [no date given] [1st published in book]. OC, vol. 4, pp. 92-93.

- XVII. “Un chemin de fer négatif” (A Negative Railway] [no date given] [1st published in book]. OC, vol. 4, pp. 93-94.

- XVIII. “Il n'y a pas de principes absolus” (There are no Absolute Principles) [no date given] [1st published in book]. OC, vol. 4, pp. 94-97.

- XIX. “Indépendance nationale” (National Independence) [no date given] [1st published in book]. OC, vol. 4, pp. 97-99.

- XX. “Travail humain, travail national” (Human Labor and Domestic Labor) [no date given] [1st published in book]. OC, vol. 4, pp. 100-05.

- XXI. “Matières premières” (Raw Materials) [no date given] [1st published in book]. OC, vol. 4, pp. 105-15.

- XXII. “Métaphores” (Metaphors) [no date given] [1st published in book]. OC, vol. 4, pp. 115-19.

- “Conclusion” (Conclusion) [dated “Mugron, 2 November, 1845”] [1st published in book]. OC, vol. 4, pp. 119-26.

The French printing history of the Economic Sophisms Series I is as follows. The 1st collection of Economic Sophisms (known as Series I) was published, according to Paillottet, at the end of 1845 (probably December) but all the printed copies bear the date 1846. It consisted of 22 essays, the first 11 of which had appeared in the April, July, and October issues of the Journal des Économistes. The last group of 11 articles were printed for the first time. The Economic Sophisms Series I continued to be published as a separate volume until 1851 with the appearance of a 4th edition. [2nd ed. in 1846, 3rd ed. 1847]. The first edition to combine both SI and SII was a Belgian edition of 1851. After the publication of the Oeuvres complètes (1st ed. in 1854) both SI and SII appeared together in vol. 4. SI was listed as being the 5th edition in 1854, the 6th edition in both 1863 and 1873.

- Sophismes économiques, par M. Frédéric Bastiat. Membre du Conseil général des Landes. (Paris: Guillaumin, 1846). [probably the 1st edition]

- Sophismes économiques, par M. Frédéric Bastiat. Membre correspondant de l"Institut et du Conseil général des Landes. 2e édition (Paris: Guillaumin, 1846).

- Sophismes économiques, par M. Frédéric Bastiat. Membre correspondant de l"Institut et du Conseil général des Landes. 3e édition (Paris: Guillaumin, 1847).

- Sophismes économiques, par Frédéric Bastiat. Première série. 4e édition. (Paris: Guillaumin, 1851).

1 (Paillottet’s note).The small volume containing the first series of Economic Sophisms was published at the end of 1845. Several of the chapters it contained had already been published by the Journal des Economistes in issues that appeared in April, July and October of the same year. [See “A Note on the Publishing History of the Economic Sophisms” for a more detailed discussion.]

2 [DMH - See “A Note on the Publishing History of the Economic Sophisms” for a more detailed discussion.]

3 Frédéric Bastiat, Sophismes économiques (Paris: Guillaumin, 1846), 166 pp.; Frédéric Bastiat, Sophismes économiques (Paris: Guillaumin, 1846. 2nd ed.), 188 pp. The Biblithèque nationale de France also lists a 4th edition of Series I published in 1851: Frédéric Bastiat, Sophismes économiques (Paris: Guillaumin, 1851), 188 pp.

4 "Sophismes économiques," JDE, avril 1845, T. 11, pp. 1-16; "Sophismes économiques (suite)," JDE, juillet 1845, T. 11, pp. 345-360; "Sophismes économiques (suite)," JDE, octobre 1845, T. 12, pp. 201-215.

[Author’s Introduction to Economic Sophisms] (final draft)↩

Publishing history- Original title, place and date of publication: [No title given] [1st published in book].

- Published as book or pamphlet: ES1 1st French edition 1846.

- Location in Paillottet's edition: Oeuvres complètes (1st ed. 1854-55), Vol. 4: Sophismes économiques. Petits pamphlets I. (1854), 5th ed., pp. 1-5.

- Previous translation: 1st English ed. 1846, 1st American ed. 1848, FEE ed. 1964. See “Note on the Publishing History.”

In political economy there is a lot to learn and very little to do. (Bentham)5 6

In this small volume, I have sought to refute a few of the arguments against the deregulation of trade.

This is not a conflict that I am entering into against protectionists. It is a principle that I am attempting to instill into the minds of sincere men who hesitate because they doubt.

I am not one of those who say: “Protection is based on interests.” I believe that it is based on error or, if you prefer, on half-truths. Too many people fear freedom for this apprehension not to be sincere.

This is setting my sights high, but I must admit that I would like this small work to become in some way a manual for men called upon to decide between the two principles. When you do not possess a long-standing familiarity with the doctrine of freedom, protectionist sophisms will constantly come to one’s mind in one form or another. To release it from them, a long effort of analysis is required on each occasion, and not everyone has the time to carry out this task, least of all the legislators. This is why I have tried to do it all at once.

But, people will say, are the benefits of freedom so hidden that they are apparent only to professional economists?

Yes, we agree that our opponents in the debate have a clear advantage over us. They can set out a half-truth in a few words, and to show that it is a half-truth we need long and arid dissertations.

This is in the nature of things. Protection brings together in one single point all the good it does and distributes among the wider mass of people the harm it inflicts. One is visible to the naked eye, the other only to the mind’s eye.7 — It is exactly the opposite for freedom.

This is so for almost all economic matters.

If you say: Here is a machine that has thrown thirty workers out into the street ;

Or else: Here is a spendthrift who will stimulate all forms of industry;

Or yet again: The conquest of Algiers8 has doubled Marseille’s trade;

Or lastly: The budget assures the livelihood of one hundred thousand families.

You will be understood by everyone, and your statements are clear, simple, and true in themselves. You may deduce the following principles from them:

Machines are harmful;

Luxury, conquest, and heavy taxes are a blessing;

And your theory will have all the more success in that you will be able to support it with irrefutable facts.

We, on the other hand, cannot stick to one cause and its immediate effect. We know that this effect itself becomes a cause in its turn. To judge a measure, it is therefore necessary for us to follow it through a sequence of results up to its final effect. And, since we must give utterance to the key word, we are reduced to reasoning.

But right away here we are, assailed by these cries, “You are theorists, metaphysicians, ideologues,9 utopians,10 and in thrall to rigid principles,” and all the prejudices of the public are turned against us.

What are we to do, therefore? Call for patience and good faith in the reader and, if we are capable of this, cast into our deductions such vivid clarity that the truth and falsehood stand out starkly in order for victory to be won either by restriction or freedom, once and for all.

I must make an essential observation at this point.

A few extracts from this small volume have appeared in the Journal des économistes.

In a criticism that was incidentally very benevolent, published by the Vicomte de Romanet11 (see the issues of Le Moniteur industriel dated 15 and 18 May 1845)12, he assumed that I was asking for customs dues to be abolished. M. de Romanet is mistaken. What I am asking for is the abolition of the protectionist regime. We do not refuse taxes to the government; what we would like, if possible, is to dissuade those being governed from taxing each other. Napoleon said: “Customs dues ought not to be a fiscal instrument, but a means of protecting industry.”13 We plead the contrary and say: “Customs dues must not be an instrument of mutual plunder in the hands of workers, but it can be a fiscal instrument that is as good as any other.” We are so far, or to involve only me in the conflict, I am so far from demanding the abolition of customs dues that I see in them a lifeline for our finances.14 I believe that they are likely to produce huge revenues for the Treasury, and if my idea is to be expressed in its entirety, at the snail’s pace that sound economic doctrine takes to circulate, I am counting more on the needs of the Treasury than on the force of enlightened public opinion for trade reform to be accomplished.

But finally what are your conclusions, I am asked.

I have no need of conclusions. I am opposing sophisms, that is all.

But, people continue, it is not enough to destroy, you have to build. My view is that in the destruction of an error the truth is created.

After that, I have no hesitation in expressing my hope. I would like public opinion to be persuaded to ratify a customs law that lays down terms of approximately this order:

Objects of prime necessity shall pay an ad valorem duty of 5%

Objects of normal usefulness 10%

Luxury objects 15 or 20%

Furthermore, these distinctions are taken from an order of ideas that is totally foreign to political economy as such, and I am far from thinking that they are as useful and just as they are commonly supposed to be. However, that is another story.

Endnotes5 Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) was the founder of the school of thought known as utilitarianism and influenced a group of political and economic reformers in the early 19th century known as the Philosophic Radicals. It is interesting that Bastiat chose two passages from Bentham's Théorie des peines et des récompenses (1811) as the opening for both the First and Second Series of the Economic Sophisms. See the glossary entry on "Bentham."

6 Some of Jeremy Bentham’s writings appeared first in French as a result of the work of his colleague Étienne Dumont, who translated, edited, and published several of Bentham’s works in Switzerland. The quotation above comes from Dumont’s Théorie des peines et des recompenses, (1811), p. 270. It is also possible that Bentham was the inspiration behind Bastiat’s choice of words for the title of this series of articles known as “Economic Sophisms.” Bentham used Dumont to edit some of his unpublished manuscripts and to prepare them for publication in French. One of these texts was Traité des sophismes politiques, which appeared in 1816. An English version of the book appeared with the editorial assistance of the Benthamite Peregrine Bingham the Younger, the Handbook of Political Fallacies, which appeared in 1824. See the introduction to Bentham, Handbook of Political Fallacies; and Bentham, The Works of Jeremy Bentham, vol. 2, “The Book of Fallacies: From Unfinished Papers of Jeremy Bentham” (</title/1921/114047>). Bentham also wrote an attack on the idea of natural rights as expressed in the French “Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen” (1789) under the title of “Anarchical Fallacies” (written 1796 but not published until 1843) (/title/1921/114226). See also Waldron, Nonsense upon Stilts. Bentham’s famous dismissal of natural rights as “nonsense upon stilts” can be found in this volume: “Natural rights is simple nonsense: natural and imprescriptible rights, rhetorical nonsense,—nonsense upon stilts” (/title/1921/114230/2345508).

7 (Paillottet’s note) This glimpse gave rise later to the pamphlet entitled What Is Seen and What Is Not Seen, which is included in this volume [see this volume, pp. 000—00].

8 Algeria was invaded and conquered by France in 1830 and the occupied parts were annexed to France in 1834. According to the new constitution of the Second Republic (1848) it was declared that Algeria was no longer a colony but an integral part of France (with three Départements) and that the emigration of French settlers would be officially encouraged and subsidized by the government. These policies were vigorously opposed by Bastiat. See the glossary entry on “Algeria.”

9 The theory of "Idéologie" had a specific meaning in the early 19th century. It referred to the ideas of Étienne Condillac (1715-1780) who believed that all ideas were the result of sensations and a wrote a pioneering treatise on economics, Commerce and Government (1776). More especially the word refers to the work of Destutt de Tracy who coined the term "idéologie". He was part of a movement in the 1790s called the "Idéologues" and their belief in constitutional government and free markets incurred the wrath of Napoleon. Jefferson translated one of Tracy's volumes on Ideology into English, with the title Treatise of Political Economy (1817). See the glossary entries on "Condillac" and "Destutt de Tracy".

10 See the glossary entry on “Utopias.”

11 Auguste, Vicomte de Romanet (n.d.), was a staunch protectionist who served on the Conseil général de l'agriculture, du commerce, et des manufactures. See the glossary entry on “Romanet.”

12 Le Moniteur industriel was the journal of the protectionist "Association pour la défense du travail national" (Association for the Defense of National Employment) founded by Mimerel de Roubaix in 1846. See the glossary entries on “Le Moniteur industriel,” “Mimerel,” and “Association for the Defense of National Employment”.

13 There are remarks about tariffs and protection for French industry scattered throughout the Mémoires of Napoleon. His most direct comments come in a discussion of the Continental System he introduced in November 1806 to weaken the British economy by preventing the sale of British goods in Europe. In the Mémoires Napoleon is very proud of his economic accomplishments and believed that the system of protection he introduced stimulated French industry enormously. "Experience showed that each day the continental system was good, because the State prospered in spite of the burden of the war… The spirit of improvement was shown in agriculture as well as in the factories. New villages were built, as were the streets of Paris. Roads and canals made interior movement much easier. Each week some new improvement was invented: I made it possible to make sugar out of turnips, and soda out of salt. The development of science was at the front along with that of industry." See Mémoires de Napoléon Bonaparte: manuscrit venu de Sainte-Hélène (Paris: Baudouin, 1821), pp. 95-99. See the glossary entry on "Napoléon."

14 Free traders like Bastiat and Cobden distinguished between two kinds of tariffs - "fiscal tariffs," which were solely designed to raise revenue for the government (it should be noted that income taxes did not exist at this time), and "protectionist tariffs" which were designed to provide government favours to particular vested interest groups. In his essay "The Utopian" (written 17 January 1847 and published in ESII as no. XI) Bastiat says he would like to reduce tariffs to 5% across the board (for both imports and exports) in order to achieve the former goal. See the glossary entries on "Cobden," “Utopias,” and “Bastiat’s Policy on Tariffs.”

I. Abundance and Scarcity [April 1845] (final draft)↩

Publishing history- Original title, place and date of publication: “Abondance, disette” (Abundance and Scarcity) [JDE, April 1845, T. 11, p. 1-8]

- Published as book or pamphlet: ES1 1st French edition 1846.

- Location in Paillottet's edition: Oeuvres complètes (1st ed. 1854-55), Vol. 4: Sophismes économiques. Petits pamphlets I. (1854), 5th ed., pp. 5-14.

- Previous translation: 1st English ed. 1846, 1st American ed. 1848, FEE ed. 1964. See “Note on the Publishing History.”

What is better for mankind and society, abundance or scarcity?

What, people will exclaim, is that a question to ask? Has it ever been stated or is it possible to assert that scarcity is the basis of man’s well-being?

Yes, that has been claimed; yes, it has been asserted. It is asserted every day, and I have no fear in saying that the theory of scarcity is by far the more popular. It is the subject of conversation in the journals, books, and on the rostrum, and although this may appear extraordinary it is clear that political economy will have fulfilled its task and its practical mission when it has popularized and made irrefutable this very simple proposition: “Mankind’s wealth lies in the abundance of things.”

Do we not hear this everyday: “Foreigners are going to swamp us with their products”? We therefore fear abundance.

Has M. de Saint-Cricq15 not said: “Production is too high”? He therefore feared abundance.

Do workers not smash machines? They are therefore terrified of excess production or, in other words, abundance.

Has M. Bugeaud16 not pronounced these words: “Let bread become expensive and farmers will be rich!”? Well, bread can become expensive only if it becomes scarce; therefore M. Bugeaud was recommending scarcity.

Has not M. d’Argout17 used the very fact of the productive capacity of the sugar industry as an argument against it? Has he not said: “Beetroot has no future, and its cultivation could not be expanded, since if just a few hectares per department were allocated to it this would meet the entire consumption needs of France.” Therefore, in his eyes, good lies in lack of production, or scarcity, and harm in fertility and abundance.

Do La Presse,18 Le Commerce,19 and the majority of daily newspapers not publish one or more articles each morning to demonstrate to the Chambers and the government that it would be sound policy to raise the price of everything by law through the operation of tariffs? Do the three powers of state20 not comply every day with this injunction from the regular press? Now tariffs raise the price of things only because they decrease the quantity offered in the marketplace! Therefore the papers, the Chambers, and the government put into practice the theory of scarcity, and I was right to say that this theory is by far the most popular one.

How has it come about that in the eyes of workers, political writers, and statesmen abundance is shown as something to be feared and scarcity as being advantageous. I propose to go back to the source of this illusion.

We note that men become rich to the extent that they earn a good return from their work, that is to say from what they sell at the highest price. They sell at the highest price in proportion to the rarity, that is to say the relative shortage, of the type of good their efforts produce. We conclude from this that, as far as they are concerned at least, scarcity makes them rich. When this reasoning is applied successively to all people who work, the theory of scarcity is thereby deduced. From this we move to its application, and in order to benefit all these people, high prices and the scarcity of all goods are provoked artificially by means of prohibition, restriction, the suppression of machines, and other similar means.

This is also true for abundance. We observe that when a product is plentiful it is sold at a low price and therefore producers earn less. If all producers are in this situation, they all become poor and it is therefore abundance that ruins society. And, since all beliefs attempt to become reality, in a great many countries, we see laws made by men combating the abundance of things.

This sophism, expressed as a general statement, would perhaps have little effect; but when it is applied to a particular order of facts, to such and such a branch of production, or to a given class of workers, it is extremely specious, and this can be explained. It is a syllogism that is not false but incomplete. Now, whatever truth there is in a syllogism is always and necessarily available to cognitive inspection. But the incomplete element is a negative phenomenon, a missing component which is very possible and even very easy not to take into account.

Man produces in order to consume. He is both producer and consumer. The reasoning that I have just set out considers him only from the first of these points of view. From the second, the opposite conclusion would have been reached. Could we not say in fact:

The consumer is all the richer when he buys everything cheaply. He buys things cheaply the more abundant they are; therefore abundance makes him rich. This reasoning, when extended to all consumers, would lead to the theory of abundance!

It is the way in which the concept of trade is imperfectly understood that produces these illusions. If we look to our own personal interest, we will recognize immediately that it has a twin nature. As sellers, our interest is in things being expensive and consequently that things should be scarce; as buyers, what counts is low prices or what comes to the same thing, that things should be abundant. We cannot therefore base a line of reasoning on one or other of these interests without having established which of the two coincides and is identified with the general and constant interest of the human race.

If man were a solitary animal,21 if he worked exclusively for himself, if he consumed the fruit of his labor directly, in a word, if he did not trade, the theory of scarcity would never have been able to infiltrate the world. It is only too obvious that abundance would be advantageous to him, from wherever it arose, either as the result of his industry or the ingenious tools or powerful machines that he had invented or through the fertility of the soil, the generosity of nature or even a mysterious invasion of products which the waves brought from elsewhere and washed up on the beach. Never would a solitary man, seeking to spur on his own work or to secure some support for it, envisage breaking instruments that spared him effort, or neutralizing the fertility of the soil or throwing back into the sea any of the advantageous goods it had brought him. He would easily understand that work is not an aim but a means, and that it would be absurd to reject the aim for fear of damaging the means. He would understand that if he devotes two hours a day to providing for his needs, any circumstance (machine, fertility, free gift, or anything else) that spares him one hour of this work, the result remaining the same, makes this hour available to him, and that he may devote it to increasing his well-being. In a word, he would understand that sparing people work is nothing other than progress.

But trade clouds our vision of such a simple truth. In a social state, with the division of labor it generates, the production and the consumption of an object are not combined in the same individual. Each person is led to consider his work no longer as a means but as an end. With regard to each object, trade creates two interests, that of the producer and that of the consumer, and these two interests are always in direct opposition to each other.

It is essential to analyze them and study their nature.

Let us take a producer, any producer; what is his immediate interest? It lies in these two things, 1. that the smallest possible number of people should devote themselves to the same work as him; 2. that the greatest possible number of people should seek the product of this work; political economy explains this more succinctly in these terms: supply should be very restricted and demand very high, or in yet other terms: that there should be limited competition with limitless markets.

What is the immediate interest of the consumer? That the supply of the product in question should be extensive and demand restrained.

Since these two interests are contradictory, one of them has of necessity to coincide with the social or general interest while the other runs counter to it.

But which should legislation favor as being the expression of public good, if indeed it has to favor one?

To know this, you need only examine what would happen if the secret desires of men were accomplished.

As producers, it must be agreed, each of us has antisocial desires. Are we vine growers? We would be little displeased if all the vines in the world froze, except for ours: that is the theory of scarcity. Are we the owners of foundries? We would want there to be no other iron on the market than what we brought to it, whatever the needs of the public might be, and with the deliberate intention that this public need, keenly felt and inadequately met, would result in our receiving a high price: that is also the theory of scarcity. Are we farm workers? We would say, with M. Bugeaud, “Let bread become expensive, that is to say, scarce and the farmers will get on with their business”: this is the same theory of scarcity.

Are we doctors? We could not stop ourselves from seeing that certain physical improvements, such as the improvement in a country’s health, the development of certain moral virtues such as moderation and temperance, the progress of enlightenment to the point that each person was able to take care of his own health, the discovery of certain simple drugs that were easy to use, would be so many mortal blows to our profession. Given that we are doctors, our secret desires are antisocial. I do not mean to say that doctors formulate such desires. I prefer to believe that they would joyfully welcome a universal panacea; but this sentiment reveals not the doctor but the man or Christian who, in self-denial, puts himself in the situation of the consumer. As one who exercises a profession and who draws his well-being from this profession, his consideration and even the means of existence of his family make it impossible for his desires, or if you prefer, his interests not to be antisocial.

Do we manufacture cotton cloth? We would like to sell it at a price most advantageous to us. We would readily agree that all rival factories should be prohibited and while we do not dare to express this wish publicly or pursue its total achievement with any chance of success, we nevertheless succeed to a certain extent through devious means, for example, by excluding foreign fabrics in order to reduce the quantity on offer, and thus produce, through the use of force, a scarcity of clothing to our advantage.

We could go through all forms of industry in this way and we would always find that producers as such have antisocial views. “Merchants,” says Montaigne, “do good business only when young people are led astray; farm workers when wheat is expensive; architects when houses are ruined; and officers of justice when court cases and quarrels between men occur. The very honor and practice of ministers of religion are drawn from our death and vices. No doctor takes pleasure in the health even of his friends nor soldiers in peace in the town, and so on.”22

It follows from this that if the secret wishes of each producer were realized the world would regress rapidly into barbarism. Sail would outlaw steam, oars would outlaw sail and would soon have to give up transport in favor of carts, carts would yield to mules, and mules to human carriers of bales. Wool would exclude cotton and cotton exclude wool and so on, until a scarcity of everything had made man himself disappear from the face of the earth.

Let us suppose for a moment that legislative power and public force were put at the disposal of the Mimerel Committee,23 and that each of the members making up this association had the right to require it to propose and sanction one little law: is it very difficult to guess to what codes of production the public would be subjected?

If we now consider the immediate interest of the consumer we will find that it is in perfect harmony with the general interest and with what the well-being of humanity demands. When a buyer enters the market, he wants to find it with an abundance of products. That the seasons are propitious to all harvests, that increasingly wonderful inventions bring a greater number of products and satisfactions within reach, that time and work are saved, that distance dissolves, that a spirit of peace and justice allows the burden of taxes to be reduced, and that barriers of all sorts fall: in all this the immediate interest of the consumer runs parallel with the public interest properly understood . He may elevate his secret desires to the level of illusion or absurdity without his desires ceasing to be humanitarian. He may want bed and board, hearth and home, education and the moral code, security and peace, and strength and health to be obtained effortlessly, without work or measure, like dust in the road, water in the stream, the air or the light that surrounds us, without the achievement of such desires being contrary to the good of society.

Perhaps people will say that if these desires were granted, the work of the producer would be increasingly restricted and would end by ceasing for lack of sustenance. Why though? Because, in this extreme supposition, all imaginable needs and all desires would be completely satisfied. Man, like the Almighty, would create everything by a single act of will. Would someone like to tell me, on such an assumption, what would there be to complain about in productive economic activity?

I imagined just now a legislative assembly made up of workers,24 of which each member would formulate into law his secret desire as a producer, and I said that the code that would emerge from this assembly would be systematic monopoly, the theory of scarcity put into practice.

In the same way, a Chamber in which each person consults only his immediate interest as a consumer would lead to the systematic establishment of freedom, the suppression of all restrictive measures, and the overturning of all artificial barriers, in a word, the realization of the theory of abundance.

From this it follows:

That to consult the immediate interest of production alone is to consult an antisocial interest;

That to make the immediate interest of consumption the exclusive criterion is to adopt the general interest.

May I be allowed to stress this point of view once more at the risk of repeating myself?

There is radical antagonism between sellers and buyers.25

Sellers want the object of the sale to be scarce, in short supply and at a high price;

Buyers want it to be abundant, available everywhere at a low price.

The laws, which ought at least to be neutral, take the side of sellers against buyers, of producers against consumers, of high prices against low prices,26 and of scarcity against abundance.

They act, if not intentionally at least in terms of their logic, according to this given assumption: A nation is rich when it lacks everything.

For they say: “It is the producer we should favor by ensuring him a proper market for his product. To do this, we have to raise its price. To raise its price, the supply has to be restricted and to restrict the supply is to create scarcity.”And look: let me suppose that right now when these laws are in full force a detailed inventory is taken, not in value but in weight, measures, volumes, and quantities of all the objects existing in France that are likely to satisfy the needs and tastes of her inhabitants, such as wheat, meat, cloth, canvas fuel, colonial goods, etc.

Let me further suppose that on the following day all the barriers that prevent the introduction into France of foreign products are overturned.

Lastly, in order to assess the result of this reform, let me suppose that three months later, a new inventory is taken.

Is it not true that we would find in France more wheat, cattle, cloth, canvas, iron, coal, sugar, etc. on the second inventory than at the time of the first?

This is so true that our protective customs duties have no other aim than to prevent all of these things from reaching us, to restrict their supply and to prevent a decrease in their price and therefore their abundance.

Now, I ask you, are the people better fed under the empire of our laws because there is less bread, meat, and sugar in the country? Are they better clad because there is less yarn, canvas, and cloth? Are they better heated because there is less coal? Are they better assisted in their work because there is less iron and copper, fewer tools and machines?

But people will say: if foreigners swamp us with their products, they will carry off our money.

What does it matter? Men do not eat money; they do not clothe themselves with gold, nor heat themselves with silver. What does it matter if there is more or less money in the country, if there is more bread on the sideboard, more meat on the hook, more linen in the cupboards and more wood in the woodshed?27

I will continue to confront restrictive laws with this dilemma:

Either you agree that you cause scarcity or you do not agree.

If you agree, you are admitting by this very fact that you are doing the people as much harm as you can. If you do not agree, then you are denying that you have restricted supply and caused prices to rise, and consequently you are denying that you have favored producers.

You are either disastrous or ineffective. You cannot be useful.28

Endnotes15 Pierre Laurent Barthélemy, comte de Saint Cricq (1772-1854) was a protectionist Deputy who became Director General of Customs (1815), president of the Trade Council, and then Minister of Trade and Colonies (1828-29). See the glossary entry on "Saint Cricq."

16 Bugeaud, Thomas, marquess de Piconnerie, duc d’Isly (1784-1849) had a distinguished military career under Napoleon fighting the partisans in Spain. After the 1830 Revolution he became a conservative deputy who supported a policy of protection for agriculture. In 1840 he was appointed the Governor of Algeria by Thiers. See the glossary entry on “Bugeaud.”

17 Antoine Maurice Appolinaire, Comte d'Argout (1782-1858), was the Minister for the Navy and Colonies, then Commerce, and Public Works during the July Monarchy. In 1834 he was appointed Governor of the Bank of France. See the glossary on “d’Argout.”

18 La Presse was a widely circulated daily newspaper under the control of the politician and businessman Émile de Girardin (1806-81). See the glossary entry on "La Presse" and “French Newspapers” in Appendix 2 “The French State and Politics.”

19 Le Commerce is possibly a reference to Le Constitutionnel which began in 1815 but had many name changes throughout its existence, including le Journal du Commerce from 1817. During the July Monarchy it sided with the policies of Thiers. See the glossary entries on "Le Commerce" and “French Newspapers.”

20 The King, the Chamber of Peers, and the Chamber of Deputies. See the glossary entry on “The Chamber of Deputies.”

21 Without mentioning him by name, Bastiat is referring here to the activities of Robinson Crusoe which he used several times in the Economic Sophisms and the Economic Harmonies as a thought experiment to explore the nature of economic action. See the glossary entry on "Crusoe Economics."

22 Montaigne, Essais de Montaigne, vol. 1, chap. 21, “Le Profit d’un est dommage de l’autre” (One man’s gain is another man’s loss), pp. 130-31. Sometime in 1847 Bastiat wrote an introduction to a chapter on this very topic. He called this phrase the “classical example of a sophism, the root stock sophism from which comes multitudes of sophisms.” Republished in this volume as ES3 15. Michel de Montaigne (1533-92) was one of the best-known and best-admired writers of the Renaissance. His Essays (first published in 1580) were a thoughtful meditation on human nature in the form of personal anecdotes infused with deep philosophical reflections. See the glossary entry on “Montaigne.”

23 There are two protectionist bodies which are referred to as the "Mimerel Committee." Pierre Mimerel de Roubaix (1786-1872) was a textile manufacturer and politician from Roubaix who was a vigorous advocate of protectionism. In 1842 he founded a pro-tariff "Comité de l'industrie" (Committee of Industry) in his home town to lobby the government for protection and subsidies. This Committee, known as the Mimerel Committee, was expanded in 1846 into a national body called the "Association pour la défense du travail national" (Association for the Defense of National Employment) in order to better counter the growing interest in Bastiat's Free Trade Association which had also been established in that year. Mimerel and Antoine Odier (1766-1853) sat on the Association's Central Committee which was commonly referred to as the "Mimerel Committee” or the "Odier Committee." See the glossary entries on "Mimerel," "Odier," "Mimerel Committee," and the "Association for the Defense of National Employment."

24 In ES 2 IV. “The Lower Council of Labour” Bastiat satirizes the Superior Council of Commerce which was a body within the Ministry of Trade which served the interests of producers by inventing an “Inferior (or Lower) Council of Labour” which would serve the interests of “proper workers.” They of course came to a very different conclusion concerning the merits of protectionism. See the glossary entry on the “Superior Council of Commerce.”

25 (Paillottet’s note) The author amended the terms of this proposition in a later work. See Economic Harmonies, chapter XI (OC, vol. 6, chap. 11, “Producteur, consommateur”).

26 (Bastiat’s note) In French we do not have a noun that expresses the opposite concept to expensiveness (cheapness [in English in the original]). It is rather remarkable that popular instinct expresses this concept by the following paraphrase: "marché avantageux, bon marché." (an advantageous market, a good market). Prohibitionists should change this locution. It implies an economic system that is quite contrary to theirs.

27 See ES1 XI. “Nominal Prices” for a more detailed discussion of this topic, below pp. ???

28 (Paillottet’s note) The author has dealt with this subject in greater detail in chapter XI of the Economic Harmonies [see note 3, above] and also in another form in the article entitled Abundance written for the Dictionary of Political Economy, which we have included at the end of the fifth volume. [Bastiat’s article “Abondance” appeared in the Dictionnaire de l’économie politique, vol. 1, pp. 2–4.]

II. Obstacle and Cause [April 1845] (final draft)↩

Publishing history- Original title, place and date of publication: “Obstacle, cause” (Obstacle and Cause] [JDE, April 1845, T. 11, p. 8-10].

- Published as book or pamphlet: ES1 1st French edition 1846.

- Location in Paillottet's edition: Oeuvres complètes (1st ed. 1854-55), Vol. 4: Sophismes économiques. Petits pamphlets I. (1854), 5th ed., pp. 15-18.

- Previous translation: 1st English ed. 1846, 1st American ed. 1848, FEE ed. 1964. See “Note on the Publishing History.”

The obstacle taken for the cause—scarcity taken for abundance: this is the same sophism under another guise. It is a good thing to examine it from all sides.

Man originally lacks everything.

Between his destitution and the satisfaction of his needs there is a host of obstacles, which it is the purpose of work to overcome. It is an intriguing business trying to find how and why these same obstacles to his well-being have become in his eyes the cause of his well-being.

I need to transport myself a hundred leagues away. But between the points of departure and arrival there are mountains, rivers, marshes, impenetrable forests, evil doers, in a word, obstacles, and in order to overcome these obstacles I have to make a great deal of effort or, what comes to the same thing, others have to make a great deal of effort and have me pay the price for this. It is clear that in this respect I would have been in a better situation if these obstacles did not exist.

To go through life and travel along the long succession of days that separates the cradle from the tomb, man needs to assimilate a prodigious quantity of food, protect himself against the inclemency of the seasons, and preserve himself from or cure himself of a host of ills. Hunger, thirst, illness, heat, and cold are so many obstacles that lie along his way. In his solitary state, he will have to combat them all by means of hunting, fishing, growing crops, spinning, weaving, and building houses, and it is clear that it would be better for him if there were fewer of these obstacles, or even none at all. In society, he does not have to confront each of these obstacles personally; others do this for him, and in return he removes one of the obstacles surrounding his fellow men.

It is also clear that, taking things as a whole, it would be better for men as a group, that is for society, that the obstacles should be as insignificant and as few as possible.

However, if we examine social phenomena in detail, and the sentiments of men as they have been altered by trade, we soon see how they have managed to confuse needs with wealth and obstacles with causes.

The division of labor, a result of the ability to trade, has meant that each person, instead of combating on his own all the obstacles that surround him, combats only one, and this, not for himself but for the benefit of all his fellow men, who in turn render him the same service.

Now, the result of this is that this person sees the immediate cause of his wealth in the obstacle that it is his job to combat on other people’s account. The greater, more serious, more keenly felt this obstacle is, the more his fellow men will be ready to pay him for removing it, that is to say, to remove on his behalf the obstacles that stand in his way.

A doctor, for example, does not occupy himself in baking his bread, manufacturing his instruments, weaving, or making his clothes. Others do this for him, and in return he does battle with the illnesses that afflict his patients. The more numerous, severe, and recurrent these illnesses are, the more willing or even obliged people are to work for his personal advantage. From his point of view, illness, that is to say, a general obstacle to people’s well-being, is a cause of individual well-being. All producers reason in the same way with regard to things that concern them. Ship owners make their profit from the obstacle known as distance, farmers from that known as hunger, cloth manufacturers from that known as cold. Teachers live on ignorance, gem cutters on vanity, lawyers on greed, notaries on the possibility of dishonesty, just as doctors depend on the illnesses suffered by men. It is thus very true that each occupation has an immediate interest in the continuation or even the extension of the particular obstacle that is the object of its efforts.

Seeing this, theoreticians come along and develop a theory based on these individual sentiments. They say: “Need is wealth, work is wealth; obstacles to well-being are well-being. Increasing the number of obstacles is to give sustenance to production.”

Next, statesmen come along. They have the coercive power of the state at their disposal, and what is more natural than for them to make use of it to develop and propagate obstacles, since this is also to develop and propagate wealth? For example, they say: “If we prevent iron from coming from those places in which it is plentiful, we will create an obstacle at home to our procuring it. This obstacle will be keenly felt and will make people ready to pay to be relieved of it. A certain number of our fellow citizens will devote themselves to combating it, and this obstacle will make their fortune. The greater it is, the scarcer the mineral or the more it is inaccessible, difficult to transport, and far from the centers of consumption, the more all this activity, with all its ramifications, will employ men. Let us keep out foreign iron, therefore; let us create the obstacle in order to create the work of combating it.”

The same reasoning will lead to machines being forbidden.

People will say: “Here are men who need to store their wine. This is an obstacle; here are other men whose occupation is to remove it by manufacturing barrels. It is thus a good thing that this obstacle exists, since it supplies a part of national work and enriches a certain number of our fellow citizens. However, here comes an ingenious machine that fells oak trees, squares them and divides them into a host of staves, assembles these and transforms them into containers for wine. The obstacle has become much less and with it the wealth of coopers. Let us maintain both through a law. Let us forbid the machine.”

In order to get to the bottom of this sophism you need only say to yourself that human work is not an aim but a means. It never remains unused. If it lacks one obstacle, it turns to another, and the human race is freed from two obstacles by the same amount of work that removed a single one. If ever the work of coopers became superfluous, they would turn to something else. “But with what” people will ask, “would it be paid?” Precisely with what it is paid right now, for when one quantity of labor becomes available following the removal of an obstacle, a corresponding quantity of money also becomes available. To say that human labor will be brought to an end for lack of employment you would have to prove that the human race will cease to encounter obstacles. If that happened, work would not only be impossible, it would be superfluous. We would have nothing left to do because we would be all powerful and we would just have to utter a fiat for all our needs and desires to be satisfied.29

Endnotes29 (Paillottet’s note) See chapter XIV of the second series of Sophisms [see this volume, “Something Else,” pp. 000—00] and chapters III and XI of the Economic Harmonies on the same subject (OC, vol. 6, chap. 3, “Des besoins de l’homme,” and chap. 11, “Producteur, consommateur”).

III. Effort and Result [April 1845] (final draft)↩

Publishing history- Original title, place and date of publication: “Effort, résultat” (Effort and Result) [JDE, April 1845, T. 11, p. 10-16].

- Published as book or pamphlet: ES1 1st French edition 1846.

- Location in Paillottet's edition: Oeuvres complètes (1st ed. 1854-55), Vol. 4: Sophismes économiques. Petits pamphlets I. (1854), 5th ed., pp. 19-27.

- Previous translation: 1st English ed. 1846, 1st American ed. 1848, FEE ed. 1964. See “Note on the Publishing History.”

We have just seen that there are obstacles between our needs and their satisfaction. We manage to overcome them or to reduce them by using our various faculties. In a very general way, we may say that production is an effort followed by a result.

But against what is our well-being or wealth measured? Is it on the result of the effort? Is it on the effort itself? There is always a ratio between the effort employed and the result obtained. Does progress consist in the relative increase of the second or of the first term of this relationship?

Both of these theses have been advocated; in political economy, they divide the field of opinion.

According to the first thesis, wealth is the result of output. It increases in accordance with the increase in the ratio of the result to the effort. Absolute perfection, of which the exemplar is God, consists in the infinite distancing of two terms, in this instance: effort nil; result infinite.

The second thesis claims that it is the effort itself that constitutes and measures wealth. To progress is to increase the ratio of the effort to the result. Its ideal may be represented by the effort, at once eternal and sterile, of Sisyphus.30 31

Naturally, the first welcomes everything that tends to decrease the difficulties involved and increase the product: the powerful machines that add to human powers, the trade that enables better advantage to be drawn from the natural resources spread to a greater or lesser extent over the face of the earth, the intelligence that makes discoveries , the experience that verifies these discoveries, the competition that stimulates production, etc.

Logically, by the same token, the second willfully summons up everything whose effect is to increase the difficulties of production and decrease the output: privileges, monopolies, restrictions, prohibitions, the banning of machines, sterility, etc.

It is fair to note that the universal practice of men is always directed by the principle of the first doctrine. Nobody has ever seen and nobody will ever see anyone working, whether he be a farmer, manufacturer, trader, artisan, soldier, writer, or scholar, who does not devote the entire force of his intelligence to doing things better, faster, and more economically, in a word, to doing more with less.

The opposite doctrine is practiced by theoreticians, deputies, journalists, statesmen, and ministers, in a word men whose role in this world is to carry out experiments on society.

Again it should be noted that, with regard to things that concern them personally, they, like everybody else in the world, act on the principle of obtaining from work the greatest number of useful results possible.

You may think I am exaggerating, and that there are no real Sisyphists.

If you mean that, in practice, the principle is not pushed to the limit of its consequences, I would readily agree with you. Actually, this is always the case when people start from a false principle. It soon leads to results that are so absurd and harmful that that one is simply forced to abandon it. For this reason, very practical productive activity never accepts Sisyphism: punishment would follow errors too closely for them not to be revealed. However, with regard to speculative theories of industrial activity, such as those developed by theoreticians and statesmen, a false principle may be followed for a long time before people are made aware of its falsity by complicated consequences of which moreover they are ignorant, and when at last they are revealed, and action is taken in accordance with the opposing principle, people contradict themselves and seek justification in this incomparably absurd modern axiom: in political economy there is no absolute principle.32

Let us thus see whether the two opposing principles that I have just established do not hold sway in turn, one in actual production and the other in the legislation regulating production.

I have already recalled something M. Bugeaud33 has said; however, in M. Bugeaud there are two men, one a farmer and the other a legislator.

As a farmer, M. Bugeaud tends to devote all his efforts to this twin aim: to save on work and to obtain bread cheaply. When he prefers a good cart to a bad one, when he improves the quality of fertilizer, when in order to break up his soil he substitutes the action of the atmosphere for that of the harrow or the hoe as far as he can, when he calls to his assistance all the procedures in which science and experiment have shown their effectiveness, he has and can have one single goal: to reduce the ratio of the effort to the result. Actually, we have no other way of recognizing the skill of the farmer and the quality of the procedure other than measuring what they have saved in effort and added to the result. And since all the farmers around the world act according to this principle, it may be said that the entire human race aspires, doubtless to its advantage, to obtaining bread or any other product more cheaply and to reducing the effort required to have a given quantity available.

Once account has been taken of this incontrovertible tendency in human beings, it ought to be enough to show legislators the real principle of the matter, that is show them how they should be supporting productive economic activity (as far as it lies within their mission to support it), for it would be absurd to say that human laws ought to act in opposition to the laws of providence.

Nevertheless, the deputy, M. Bugeaud, has been heard to exclaim, “I do not understand the theory of low prices; I would prefer to see bread more expensive and work more plentiful.” And as a result, the deputy for the Dordogne has voted for legislative measures whose effect has been to hamper trade precisely because it indirectly procures us what direct production can supply us only at a higher cost.

Well, it is very clear that M. Bugeaud’s principle as a deputy is diametrically opposed to that of M. Bugeaud as a farmer. If he were consistent with himself, he would vote against any restriction in the Chamber or else he would carry on to his farm the principles he proclaims from the rostrum. He would then be seen to sow his wheat on the most infertile of his fields, since he would then succeed in working a great deal for little return. He would be seen to forbid the use of the plough, since cultivation using his nails would satisfy his double desire of making bread more expensive and work more plentiful.

The avowed aim and acknowledged effect of restriction is to increase work.

It also has the avowed aim and acknowledged effect of raising prices, which is nothing other than making products scarce. Thus, when taken to its limit, it is pure Sisyphism as we have defined it: infinite work, product nil.

Baron Charles Dupin34, said to be a leading light among the peers in economic science, accuses the railway of harming shipping, and it is clear that it is the nature of a more perfect means to restrict the use of a means that is comparatively rougher. However, the railway can harm shipping only by diverting transport to itself; it can do so only by carrying it out more cheaply, and it can carry it out more cheaply only by reducing the ratio of the effort used to the result obtained, since this is what constitutes the lower cost. When, therefore, Baron Dupin deplores this reduction of work for a given result, he is following the lines of the doctrine of Sisyphism. Logically, since he prefers ships to rail, he ought to prefer carts to ships, packhorses to carts, and backpacks to all other known means of transport, since this is the means that requires the greatest amount of work for the least result.

“Work constitutes the wealth of a people.” said M. de Saint-Cricq, this minister of trade who imposed so many impediments to trade.35 It should not be believed that this was an elliptical proposition which meant: “The results of work constitute the wealth of a people.” No, this economist genuinely meant to say that it is the intensity of labor that measures wealth, and proof of this is that, from one inference to another, one restriction to another, he led France and considered he was doing a good thing in this, to devote twice as much work to acquire the same amount of iron, for example. In England, iron then cost 8 fr.; in France it cost 16 fr. If we take a day’s work to cost 1 fr. it is clear that France could, through trade, procure a quintal of iron for eight days taken from national work as a whole. Thanks to M. de Saint-Cricq’s restrictive measures, France needed sixteen days of work to obtain a quintal36 of iron through direct production. Double labor for identical satisfaction, therefore double wealth; here again wealth is measured not by outcomes but by the intensity of the work. Is this not Sisyphism in all its glory?

And so that there is no possible misunderstanding, the minister is careful to take his idea further, and in the same way as he has just called the intensity of labor wealth, he is heard calling the abundance resulting from production, or things likely to satisfy our needs, poverty. “Everywhere”, he says, “machines have taken the place of manpower; everywhere, there is an overabundance of production; everywhere the balance between the ability to produce and the means of consumption has been destroyed.” We see that, according to M. de Saint-Cricq, if France was in a critical situation it was because it produced too much and its production was too intelligent and fruitful. We were too well fed, too well clothed, too well provided for in every way. Production was too fast and exceeded all our desires. An end had to be put to this scourge, and to this end we had to force ourselves, through restrictions, to work more to produce less.

I have also recalled the opinion of another minister of trade, M. d’Argout.37 It is worth our spending a little time on it. As he wished to deliver a terrible blow to sugar-beet , he said, “Growing sugar-beet is doubtless useful, but its usefulness is limited. It does not involve the gigantic developments that people were happy to forecast for it. To be convinced of this, you just have to note that this crop will of necessity be restricted to the limits of consumption. Double or triple current consumption in France if you want, you will always find that a very minimal portion of the land would be enough to meet the needs of this consumption. (This is certainly a strange complaint!). Do you want proof of this? How many hectares38 were planted with sugar-beet in 1828? There were 3,130, which is equivalent to 1/10540th of the cultivatable land. How many are there now that indigenous sugar39 has taken over one third of consumption? There are 16,700 hectares, or 1/1978th of the cultivatable land, or 45 square meters per commune. If we suppose that indigenous sugar had already taken over the entire consumption, we would have only 48,000 hectares planted with beetroot, or 1/680th of the cultivatable land.”40 41

There are two things in this quotation: facts and doctrine. The facts tend to establish that little land, capital, and labor is needed to produce a great deal of sugar and that each commune in France would be abundantly provided with it if it devoted one hectare of its territory to its cultivation. The doctrine consists in seeing this situation as disastrous and seeing in the very power and fruitfulness of the new industry the limit of its usefulness.

I have no need to make myself the defender of sugar-beet or the judge of the strange facts put forward by M. d’Argout,42 but it is worth examining in detail the doctrine of a statesman to whom France entrusted for many years the fate of its agriculture and trade.

I said at the beginning that there was a variable ratio between productive effort and its result; that absolute imperfection consists in an infinite effort with no result: that absolute perfection consists in an unlimited result with no effort; and that perfectibility consists in a gradual reduction in the effort compared to the result.