The Works of Bastiat 3: The Paris Writings II 1848-1850

Part 3: The “Paris” Writings II: Bastiat the Politician, Anti-Socialist, and Economist (Feb. 1848 - Dec. 1850)

[Updated: 30 March, 2018 - a "work in progress"]

New: a revised translation of The Law.

Note: We have added final draft versions of material which will appear in the Collected Works, vol.3 "Economic Sophisms and WSWNS"; and the Collected Works, vol. 4 "Miscellaneous Writings on Economics."

|

|

|

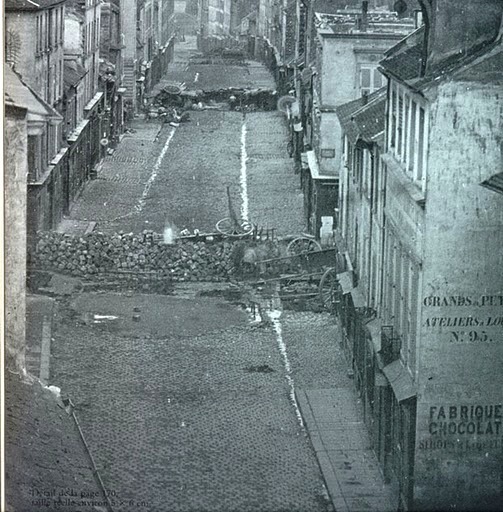

Street Barricades in Paris, June Days 1848

|

|

|

The National Assembly in Paris

|

Introduction to the Collected Works in Chronological Order

Frédéric Bastiat’s 6 volume Collected Works published by Liberty Fund is a thematic collection.

- Vol. 1: The Man and the Statesman: The Correspondence and Articles on Politics, translated from the French by Jane and Michel Willems, with an introduction by Jacques de Guenin and Jean-Claude Paul-Dejean. Annotations and Glossaries by Jacques de Guenin, Jean-Claude Paul-Dejean, and David M. Hart. Translation editor Dennis O’Keeffe (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2011). /titles/2393.

- Vol. 2: The Law, The State, and Other Political Writings, 1843–1850, Jacques de Guenin, General Editor. Translated from the French by Jane Willems and Michel Willems, with an introduction by Pascal Salin. Annotations and Glossaries by Jacques de Guenin, Jean-Claude Paul-Dejean, and David M. Hart. Translation Editor Dennis O’Keeffe. Academic Editor, David M. Hart (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2012). /titles/2450.

- Vol. 3: Economic Sophisms and “What is Seen and What is Not Seen”. Jacques de Guenin, General Editor. Translated from the French by Jane and Michel Willems, with a foreword by Robert McTeer, and an introduction and appendices by the Academic Editor David M. Hart. Annotations and Glossaries by Jacques de Guenin, Jean-Claude Paul-Dejean, and David M. Hart. Translation Editor Dennis O'Keeffe. (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2017). (Not yet online.)

- Vol. 4: Miscellaneous Works on Economics: From “Jacques-Bonhomme” to Le Journal des Économistes (forthcoming)

- Vol. 5: Economic Harmonies (forthcoming)

- Vol. 6: The Struggle Against Protectionism: The English and French Free-Trade Movements (forthcoming)

There will also be an online edition of Bastiat’s writings in chronological order. We have divided Bastiat’s works into 4 parts based upon the key periods and events in his life:

- Early Writings: The Bayonne and Mugron Years, 1819–1844

- The “Paris” Writings I: Bastiat and the Free Trade Movement (Oct. 1844 - Feb. 1848)

- The “Paris” Writings II: Bastiat the Politician, Anti-Socialist, and Economist (Feb. 1848 - Dec. 1850)

- The Unfinished Treatises: The Social and Economic Harmonies and The History of Plunder (1850–51)

For further information, see:

- the LF published edition of Bastiat’s Collected Works in 6 vols.

- the main Bastiat page in the OLL

- the Reader’s Guide to the Works of Frédéric Bastiat (1801–1850)

- the Liberty Matters discussion of Bastiat: Lead essay by Robert Leroux, “Bastiat and Political Economy” (July 1, 2013) with response essays by Donald J. Boudreaux, Michael C. Munger, and David M. Hart. </pages/bastiat-and-political-economy.

- Essays and other material about Bastiat

- Table of Contents of Bastiat’s Letters, Articles, and Books Listed in Chronological Order

The abbreviations used in this paper:

- 1847.02.14 = the work was published on Feb. 14, 1847

- ACLL = the English Anti-Corn Law League (1838-46)

- AEPS = L'Annuaire de l'économie politique et statistique (published by Guillaumin)

- ASEP = Annales de la Société d'Économie Politique. Publiées sous la direction de Alph. Courtois fils, secrétaire perpétuel, Tome premier 1846-1853 (Paris: Guillaumin,1889).

- CRANC = Compte rendu des séances de l'Assemblée Nationale Constituante

- CRANL = Compte rendu des séances de l'Assemblée Nationale Législative

- CF = Le Courrier française

- CH = Letters from Lettres d'un habitant des Landes, Frédéric Bastiat. Edited by Mme Cheuvreux. (1877)

- CW = the Collected Works of Frédéric Bastiat (Liberty Fund edition)

- CW1 = volume 1 of The Collected Works of Frédéric Bastiat

- OC = Oeuvres complètes de Frédéric Bastiat (Paillottet/Guillaumin edition)

- OC1.9 = the 9th article in vol. 1 of the Oeuvres complètes

- DEP = Dictionnaire d'économie politique

- DMH = text discovered by David M. Hart which is not in Paillottet's OC

- EH = Economic Harmonies

- EH1 = Economic Harmonies - the incomplete edtion publlished by FB during his lifetime in Jan. 1850 (11 chaps.)

- EH2 = Economic Harmonies - the expanded edtion with 22 chaps. publlished by Paillottet and Fontenay in July 1851

- Encyclopédie du dix-neuvième siècle (1846) = Encyclopédie du dix-neuvième siècle: répertoire universel des sciences, des lettres et des arts avec la biographie de tous les hommes célèbres, ed. Ange de Saint-Priest (Impr. Beaulé, Lacour, Renoud et Maulde, 1846)

- ES1 = Economic Sophisms. First Series (published Jan. 1846)

- ES1.10 = the tenth essay in ES1

- ES2 = Economic Sophisms. Second Series (published Jan. 1848)

- ES3 = Economic Sophisms. Third Series (compiled and published by LF in 2017 in CW3)

- FEE = Foundation for Economic Education

- JB = the journal Jacques Bonhomme (June 1848)

- JCPD = the original document was unpublished and is in the possession of Jean-Claude Paul-Dejean

- JDD = Journal des débats

- JDE = Journal des Économistes

- LÉ = Le Libre-Échange

- n.d. = no date of publication is known

- OC1 = Oeuvres complètes de Frédéric Bastiat, ed. Prosper Paillottet in 6 vols. (1854–55)

- OC2 = 2nd edition of Oeuvres complètes de Frédéric Bastiat, ed. Prosper Paillottet in 7 vols. (1862–64)

- PES = Political Economy Society (Société d'économie politique)

- PP = Prosper Paillottet, the editor of FB's OC

- RF = La République française Feb.-March 1848)

- Ronce = P. Ronce, Frédéric Bastiat. Sa vie, son oeuvre (Paris: Guillaumin, 1905).

- SP = La Sentinelle des Pyrénées

- PES = Political Economy Society (Société d'Économie Politique)

- T = either means "volume" (tome) or "Text" ID number (as in T.28)

- T.1 = text number one in the chronological table of contents of his writings

- WSWNS = What Is Seen and What Is Not Seen

The full method of citation for Bastiat’s writings (which is sometimes abbreviated in this article for reasons of space):

- T.102 (1847.01.17) "L'utopiste" (The Utopian) [Le Libre-Échange, 17 January 1847] [OC4.2.11, pp. 203–12] [ES2 11, CW3, pp. 187-98]

- text number in chronological ToC, date, French title, English title, place and date of original publication, location in French OC, location in ES, location in LF's CW volume.

- Letter 3. Bayonne, 18 March 1820. To Victor Calmètes [OC1, p. 3] [CW1, pp. 28-30]

- letter number in CW1, place and date letter written, recipient, location in OC, location in LF CW

Table of Contents

- Letter 91. Paris, 25 Feb. 1848. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 92. Paris, 26 Feb. 1848. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 93. Paris, 27 Feb. 1848. To Madame Marsan

- Letter 94. Paris, 29 Feb. 1848. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 95. Paris, 4 March 1848. To M. Domenger, in Mugron

- Letter 96. Mugron, 5 Apr. 1848. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 97. Mugron, 12 Apr. 1848. To Horace Say

- Letter 98. Paris, 11 May 1848. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 99. Paris, 17 May 1848. To Madame Schwabe

- Letter 100. Paris, 27 May 1848. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 101. Paris, 9 June 1848. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 102. Paris, 24 June 1848. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 103. Paris, 27 June 1848. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 104. Paris, 29 June 1848. To Julie Marsan

- Letter 105. Paris, 1 July 1848. To M. Schwabe

- Letter 106. Paris, 7 Aug. 1848. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 107. Paris, 18 Aug. 1848. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 108. Paris, 26 Aug. 1848. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 109. Paris, 3 Sept. 1848. To M. Domenger

- Letter 110. Paris, 7 Sept. 1848. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 111. Dover, 7 Oct. 1848. To M. Schwabe

- Letter 112. Paris, 25 Oct. 1848. To M. Schwabe

- Letter 113. Paris, Nov. 1848. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 114. Paris, 14 Nov. 1848. To Madame Schwabe

- Letter 115. Paris, 26 Nov. 1848. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 116. Paris, 5 Dec. 1848. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 117. Paris, 21 Dec. 1848. To M. le Comte Arrivabene

- Letter 118. Paris, 28 Dec. 1848. To Madame Schwabe

- Letter 119. Paris, Jan. 1849. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 120. Paris, 1er Jan. 1849. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 121. Paris, 15 Jan. 1849. To M. George Wilson

- Letter 122. Paris, 18 Jan. 1849. To M. Domenger

- Letter 123. Paris, Feb. 1849. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 124. Paris, Feb. 1849. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 125. Paris, 3 Feb. 1849. To M. Domenger

- Letter 126. Paris, no date, 1849. To M. Domenger

- Letter 127. Paris, no date 1849. To M. Domenger

- Letter 128. Paris, March 1849. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 129. Paris, 11 March 1849. To Madame Schwabe

- Letter 130. Paris, 15 March 1849. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 131. Paris, 25 March 1849. To M. Domenger

- Letter 132. Paris, 8 Apr. 1849. To M. Domenger

- Letter 133. Paris, 25 Apr. 1849. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 134. Paris, 29 Apr. 1849. To M. Domenger

- Letter 135. Paris, 3 May 1849. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 136. Paris, sans date, 1849. To M. Domenger

- Letter 137. Bruxelles, hôtel de Bellevue, June 1849. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 138. Bruxelles, June 1849. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 139. Anvers, June 1849. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 140. Paris, mardi 13, summer 1849. To M. Domenger

- Letter 141. Paris, 14 July 1849. To M. Paillottet

- Letter 142. Paris, 30 July 1849. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 143. Mont-de-Marsan, 30 Aug. 1849. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 144. Mugron, 12 Sept. 1849. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 145. Mugron, 16 Sept. 1849. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 146. Mugron, 16 Sept. 1849. To Horace Say

- Letter 147. Mugron, 18 Sept. 1849. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 148. Paris, 7 Oct. 1849. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 149. Paris, 8 Oct. 1849. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 150. Paris, 14 Oct. 1849. To Madame Schwabe

- Letter 151. Paris, 17 Oct. 1849. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 152. Paris, 24 Oct. 1849. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 153. Paris, Nov. 1849. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 154. Paris, 13 Nov. 1849. To M. Domenger

- Letter 155. Paris, 13 Dec. 1849. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 156. Paris, 25 Dec. 1849. To M. Domenger

- Letter 157. Paris, 31 Dec. 1849. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 158. Paris, Jan. 1850. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 159. Paris, 2 Jan. 1850. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 160. Paris, Jan. 1850. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 161. Paris, Feb. 1850. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 162. Paris, 18 Feb. 1850. To M. Domenger

- Letter 163. Paris, March 1850. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 164. Paris, 22 March 1850. To M. Domenger

- Letter 165. Paris, 11 Apr. 1850. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 166. Bordeaux, May 1850. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 167. Mugron, 19 May 1850. To M. Paillottet

- Letter 168. Mugron, 20 May 1850. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 169. Mugron, 23 May 1850. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 170. Mugron, 27 May 1850. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 171. Mugron, 2 June 1850. To M. Paillottet

- Letter 172. Mugron, 3 June 1850. To Horace Say

- Letter 173. Mugron, 11 June 1850. To Mlle Louise Cheuvreux

- Letter 174. Eaux-Bonnes, 15 June 1850. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 175. Eaux-Bonnes, 23 June 1850. To M. Paillottet

- Letter 176. Eaux-Bonnes, 23 June 1850. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 177. Eaux-Bonnes, 24 June 1850. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 178. Eaux-Bonnes, 28 June 1850. To M. Paillottet

- Letter 179. Eaux-Bonnes, 2 July 1850. To M. Paillottet

- Letter 180. Eaux-Bonnes, 3 July 1850. To M. de Fontenay

- Letter 181. Eaux-Bonnes, 4 July 1850. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 182. Eaux-Bonnes, 4 July 1850. To Horace Say

- Letter 183. Mugron, July 1850. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 184. Mugron, 14 July 1850. To M. Cheuvreux

- Letter 185. Paris, 3 Aug. 1850. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 186. Paris, 17 Aug. 1850. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 187. Paris, 17 Aug. 1850. To the President of the Congrès de la Paix

- Letter 188. Paris, 9 Sept. 1850. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 189. Paris, 9 Sept. 1850. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 190. Lyon, 14 Sept. 1850. To M. Paillottet

- Letter 191. Lyon, 14 Sept. 1850. To Melle Louise Cheuvreux

- Letter 192. Lyon, 14 Sept. 1850. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 193. Marseille, 18 Sept. 1850. To M. Cheuvreux

- Letter 194. Marseille, 22 Sept. 1850. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 210 to Paillottet (Pisa, 30 Sept. 1850) [CW4 draft - 16 June 2017]

- Letter 195. Pisa, 2 Oct. 1850. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 211 to Paillottet (Pisa, 7 Oct. 1850) [CW4 draft - 16 June 2017]

- Letter 196. Pisa, 8 Oct. 1850. To M. Domenger

- Letter 212 to Paillottet (Pisa, 11 Oct. 1850) [CW4 draft - 16 June 2017]

- Letter 197. Pisa, 11 Oct. 1850. To M. Paillottet

- Letter 213 to M. Soustra, (Pise, 12 Oct. 1850) [CW4 draft - 16 June 2017]

- Letter 198. Pisa, 14 Oct. 1850. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 199. Pisa, 18 Oct. 1850. To Richard Cobden

- Letter 200. Pisa, 20 Oct. 1850. To Horace Say

- Letter 201. Pisa, 28 Oct. 1850. To M. le Comte Arrivabene

- Letter 202. Pisa, 29 Oct. 1850. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 214 to Paillottet (Rome, 8 Nov. 1850) [CW4 draft - 16 June 2017]

- Letter 203. Rome, 11 Nov. 1850. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 204. Rome, 26 Nov. 1850. To M. Paillottet

- Letter 205. Rome, 28 Nov. 1850. To M. Domenger

- Letter 206. Rome, 8 Dec. 1850. To M. Paillottet

- Letter 207. Rome, 14, 15, 16, 17 Dec. 1850. To Madame Cheuvreux

- Letter 208. Letter from Prosper Paillottet to Mme Cheuvreux, Rome, 22 Dec. 1850

- Letter 209. (1851.??) “Lettre non datée” (Undated letter), "Les Harmonies économiques. Lettre de M. Carey; réponse de MM. Frédéric Bastiat et A. Clément"

Bastiat's Writings after the February 1848 Revolution

- T.293 (post-1848) "On Experience and Responsibility" [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.295 (c. 1848) "Why our Finances are in a Mess" [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.186 [1848.02.26] "A Few Words about the Title of our Journal: La République française" (26 Feb. 1848, RF) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

-

Articles in La République française (26 Feb. to 14 March)

- T.186 (1848.02.26) "A Few Words about the Title of our Journal" (RF, Feb. 1848) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.187 (1848.02.27) "The Streets of Paris" (RF, Feb. 1848)

- T.188 (1848.02.27) "Under the Republic" (RF, Feb. 1848)

- T.189 (1848.02.28) "A thought in La Presse" (RF, Feb. 1848)

- T.190 (1848.02.28) "All our cooperation" (RF, Feb. 1848)

- T.191 (1848.02.28) "On Disarmament" (RF, Feb. 1848)

- T.192 (1848.02.29) "The General Good" (RF, Feb. 1848)

- T.193 (1848.02.29) "The Kings Must Disarm" (RF, Feb. 1848)

- T.194 (1848.02.29) "The Sub-Prefects" (RF, Feb. 1848) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.195 (1848.03.01) "Untitled Article" (On Diplomacy and Government Jobs) (RF, March 1848)

- T.196 (1848.03.01) "The Parisian Press" (RF, March 1848)

- T.197 (1848.03.02) "Petition from an Economist" (RF, March 1848)

- T.198 (1848.03.04) "Freedom of Teaching" (RF, March 1848)

- T.199 (1848.03.05) "The Scramble for Office" (RF, March 1848)

- T.200 (1848.03.06) "Impediments and Taxes" (RF, March 1848)

- T.201 (1848.03.12) "The Immediate Relief of the People" (RF, March 1848) [CW3 - final draft]

- T.202 (1848.03.14) "A Disastrous Remedy" (RF, March 1848)[CW3 - final draft]

- T.204 (1848.03.15) "Disastrous Illusions" (JDE, March 1848)

- T.205 (1848.03.19) "Circulars from a Government that is Nowhere to be Found" (LE, March 1848)

- T.206 (1848.03.22) "Statement of Electoral Principles. To the Electors of Les Landes, 22 March, 1848"

- T.207 (1848.03.28) "Letter to an Ecclesiastic"

- T.302 [1848.05.13] "Speaks in a Discussion in the Assembly on the Formation of Committees" (13 May 1848) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.208 (1848.05.15) "Property and Law" (JDE, May 1848)

- T.209 (1848.06) Individualism and Fraternity

- T.210 (1848.06.??) "On Religion"

- T.303 [1848.06.09] "Speaks in a Discussion of Randoing 's Proposal to increase Export Subsidies on Woollen Cloth" (9 June 1848) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

-

Articles in Jacques Bonhomme (11-20 June)

- T.211 (1848.06.11) "Freedom" (JB, June 1848)

- T.212 (1848.06.11) "The State" (JB, June 1848)

- T.213 (1848.06.11) "The National Assembly" (JB, June 1848)

- T.214 (1848.06.11) "Laissez-Faire" (JB, June 1848)

- T.216 [1848.06.15] "A Hoax" (15 June 1848, JB) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.217 [1848.06.15] "Taking Five and Returning (giving back) Four is not Giving" (15 June 1848, JB) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.218 [1848.06.20] "A Dreadful Escalation" (20 June 1848, JB) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.219 (1848.06.20) "To Citizens Lamartine and Ledru-Rollin" (JB, June 1848)

- T.215 (1848.06.15) "Justice and Fraternity" (JDE, June 1848)

- T.220 (1848.07.24) "Property and Plunder" (JDD, July 1848)

- T.304 [1848.07.26] "Speaks in a Discussion on the Decree concerning the Regulation of the Political Clubs" (26 July 1848) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.203 [1848.07.28] "A Complaint made by M. Considerant and F. Bastiat's Reply." [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.305[1848.08.09] "Report to the Assembly from the Finance Committee concerning a Grant to assist needy citizens in the Department of la Seine" (9 August 1848) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.306 [1848.08.10] "Additional Comments in the Assembly on the Report from the Finance Committee concerning a Grant to assist needy citizens in the Department of la Seine" (10 August 1848) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.221 (1848.08.13) "Letter on the Referendum for the Election of the President of the Republic" (JDL, Aug. 1848)

- T.307 [1848.08.24] "Speech in the Assembly on Postal Reform" (24 August 1848) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.222 (1848.09.25) "The State" (JDD, Sept. 1848)

- T.223 [1848.09.01] "Economic Harmonies: I, II, and III. The Needs of Man" (1 Sept., 1848, JDE) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.224 [1848.10] Bastiat's Letter to Garnier on the Right to a Job (Oct, 1848) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.273 [1848.10.10] "Comments at a Meeting of the Political Economy Society on Income Tax" (10 Oct., 1848) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.308 [1848.10.27] "Speaks in a Discussion in the Assembly on the Election of the President of the Republic" (27 Oct. 1848) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.274 [1848.12.10] "Comments at a Meeting of the Political Economy Society on the Emancipation of the Colonies" (10 Dec. 1848) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.225 [1848.12.15] "Economic Harmonies IV" (JDE, 15 Dec. 1848) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

Bastiat's Writings in 1849

- T.226 (1849.??) "On the Separation of the Temporal and Spiritual Domains"

- T.227 (1849.??) "Report Presented to the 1849 Session of the General Council of the Landes, on the Question of Common Land"

- T.228 (1849.??) "Statement of Electoral Principles in 1849"

- T.229 (1849.??) "Concerning Religion"

- T.294 [1849.??] "On the Value of Services" (c.1849-50) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.316 [1849.??] "Money and the Mutuality of Services" (c. 1849) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.231 (1849.01) Protectionism and Communism

- T.232 [1849.01.01] "The Consequences of the Reduction in the Salt Tax" (JDD, 1 Jan. 1849) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.309 [1849.01.11] "Speaks in a Discussion in the Assembly on a Proposal to change the Tariff on imported Salt" (11 Jan. 1849) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.233 (1849.01.15) "Letter from Bastiat to Mr. G. Wilson, 15 Jan. 1849" [CW6 -to come]

- T.234 [1849.02] Capital and Rent (Feb. 1849) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.235 (1849.02) Peace and Freedom or the Republican Budget

- T.275 [1849.02.10] "Comments at a Meeting of the Political Economy Society on Financial Reform" (10 Feb. 1849) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.310 [1849.02.22] "Speaks in a Discussion in the Assembly on Amending the Electoral Law" (26 Feb. 1849) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.236 (1849.03) Parliamentary Conflicts of Interest

- T.311 [1849.03.10] "Speech in the Assembly on Amending the Electoral Law (Third Reading)" (10 and 13 March 1849) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.237 (1849.03.15) Bastiat's remarks from a discussion on "Parliamentary Conflicts of Interest" (JDE, March 1849)

- T.238 (1849.04) "Statement of Electoral Principles in April 1849"

- T.239 [1849.04.15] Damned Money! (15April 1849, JDE) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.276 [1849.05.10] "Comments at a Meeting of the Political Economy Society on the Peace Congress and State support for an Experimental Socialist Community" (10 May 1849) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.230 [1849.06??] "Capital" (mid-1849, Almanac rép.) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.290 [1849.06] "When extremes meet" (June 1849) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.240 and T. 283 [1849.08.22] Speech on "Disarmament, Taxes, and the Influence of Political Economy on the Peace Movement." (22 Aug. 1849) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.312 [1849.10.06] "Speaks in a Discussion in the Assembly on changing the Law on the Appropriation of Private Property for Public Use" (6 Oct. 1849) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.277 [1849.10.10] "Comments at a Meeting of the Political Economy Society on the Limits to the Functions of the State (Part 1) and Molinari's Book" (10 Oct. 1849) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

-

T.241 [1849.10.22] Free Credit (Oct. 1849 - March 1850, Voix du peuple) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- Letter No. 1: F. C. Chevé to F. Bastiat (22 October 1849)

- Proudhon's Preface to Bastiat's First Letter

- Letter No. 2: F. Bastiat to the Editor (12 November 1849)

- Letter No. 3: P. J. Proudhon to F. Bastiat (19 November 1849)

- Letter No. 4: F. Bastiat to P. J. Proudhon (26 November 1849)

- Letter No. 5: P. J. Proudhon to F. Bastiat (3 December 1849)

- Letter No. 6: F. Bastiat to P. J. Proudhon (10 December 1849)

- Letter No. 7: P. J. Proudhon to F. Bastiat (17 December 1849)

- Letter No. 8 : F. Bastiat to P. J. Proudhon (24 December 1849)

- Long footnote from Letter 8

- Letter No. 9: P. J. Proudhon to F. Bastiat (31 December 1849)

- Letter No. 10: F. Bastiat to P. J. Proudhon (6 January 1850)

- Letter No. 11: P. J. Proudhon to F. Bastiat (21 January 1850)

- Letter No. 12: F. Bastiat to P. J. Proudhon (4 February 1850)

- Letter No. 13: P. J. Proudhon to F. Bastiat (11 February 1850)

- Letter No. 14: F. Bastiat to P. J. Proudhon (7 March 1850)

- T.242 [1849.11.10] "Comments at a Meeting of the Political Economy Society on Disarmament and the English Peace Movement" (10 Nov. 1849) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.319 [1849.11.16] "Speaks in the Assembly on the Right to Form Unions" (16 Nov. 1849) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.243 (1849.11.17) "Speech on The Repression of Industrial Unions"

- T.245 [1849.12.10] "Comments at a Meeting of the Political Economy Society on State Support for popularising Political Economy, his idea of Land Rent in Economic Harmonies, the Tax on Alcohol, and Socialism" (10 Dec. 1849) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017

- T.244 (1849.12.12) "Speech on the Tax on Wines and Spirits"

- T.245 (1849.12.15) Bastiat's comments from a discussion of Economic Harmonies and the tax on alcohol (JDE, Dec. 1849) [CW4 - to come]

Bastiat's Writings in 1850

- T.246 (1850.??) "The Three Pieces of Advice"

- T.247 (1850.??) Baccalaureate and Socialism

- T.168 [1850.??] "Liberty, Equality" (c. 1850) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.168 [1850.??] "Liberty, Equality" (c. 1850) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.301 [1850.??] "On coerced Charity" (c. 1850) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.315 [1850.??] "The Consequences of an Action" (c. 1850) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.182 [1850.??] "Our Abilities vs. Our Needs" (c. 1850) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.284 [1850.??] "A Note on Economic and Social Harmonies" (c. early 1850) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.249 (1850.01) Economic Harmonies. 1st ed. [CW5 -to come]

- T.250 [1850.01.10] "Comments at a Meeting of the Political Economy Society on the Limit to the Functions of the State" (Part 2)" (10 Jan. 1850) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.313 [1850.02.06] "Speaks in a Discussion in the Assembly on Public Education" (6 Feb. 1850) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.314 [1850.02.09] "Speaks in a Discussion in the Assembly on a Plan to give money to Workers Associations" (9 Feb. 1850) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.251 [1850.02.10] "Comments at a Meeting of the Political Economy Society on the Limits to the Functions of the State (Part 3)" (10 Feb. 1850) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.253 [1850.03.29] "The Balance of Trade" (29 March 1850) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.254 (1850.04.01) "Reflections on the Amendment of M. Mortimer-Ternaux"

- T.255 [1850.04.15] "England's New Colonial Policy. Lord John Russell's Plan" (JDE, 15 Apr. 1850) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.256 [1850.04.10] "Comments at a Meeting of the Political Economy Society on Land Credit" (10 Apr. 1850) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.257 (1850.05.15) "Plunder and Law" (JDE, May 1850)

- T.248 [1850.06??] "Abundance" (summer 1850, DEP) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.258 (1850.06) The Law [revised translation (February, 2018)]

- T.259 (1850.07) What is Seen and What is Not Seen [CW3 - final draft]

- T.278 [1850.09.10] "The Society's farewell to Bastiat at a Meeting of the PES" (10 Sept. 1850) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.292 [1850.10??] "On the Idea of Value" (late 1850) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

- T.279 [1851.01.15] "The announcements of Bastiat's death at a Meeting of the PES and in the JDE" (10, 15 Jan. 1851) [CW4 - draft 19 June 2017]

Posthumous Material

- T.260 (1851.07) Economic Harmonies (2nd ed.) [CW5 -to come]

- T.261 (1852.??) "Abundance"; "The State"; "The Law" (DEP, 1852-53) [CW4 - draft 29 Jan. 2016 version]

- T.262 (1854-55) Oeuvres complète (1st ed.)

- T.263 (1862-64) Oeuvres complète (2nd ed.)

- T.264 (1863) Oeuvres choisies, 3 vols.

- T.265 (1877.??) Lettres d’un habitant des Landes

- What is Seen and What is Not Seen (July 1850) [CW3 - final draft]

Introduction to Part 3: The “Paris” Writings II: Bastiat the Politician, Anti-Socialist, and Economist (Feb. 1848 - Dec. 1850)↩

Large armaments necessarily entail heavy taxes : heavy taxes force governments to have recourse to indirect taxation. Indirect taxation cannot possibly be proportionate, and the want of proportion in taxation is a crying injustice inflicted upon the poor to the advantage of the rich. This question, then, alone remains to be considered : Are not injustice and misery, combined together, an always imminent cause of revolutions?

(Speech to the Friends of Peace Conference, Paris, 22 Aug., 1849. CW3)

Key works from this period:

- his revolutionary street journalism in La République française (Feb.-March 1848) and Jacques Bonhomme (June 1848):

- his statement of Republican and liberal principles in T.186 “A Few Words about the Title of our Journal” (26 Feb. 1848)

- his classic essay on “the great fiction”, T.212 “The State” (June 1848) and T.222 (Sept. 1848)

- T.214 "Laissez-Faire" (June 1848)

- T.219 “To Citizens Lamartine and Ledru-Rollin” (June 1848)

- his T.238 “Statement of Electoral Principles” (April, 1849)

- the 12 anti-socialist pamphlets or “Petits Pamphlets”, such as The State (June, Sept. 1848)

- his plans for cutting taxes and the size of the military:

- T.235 Peace and Freedom or the Republican Budget (February 1849) and

- T.240 “Disarmament, Taxes, and the Influence of Political Economy on the Peace Movement” (Aug. 1849)

- his writings on money and interest:

- T.239 Damn Money! (April 1849) and

- T.241 Free Credit (October 1849 - February 1850)

- his important last works:

- T.258 The Law (June 1850) and

- T.259 What is Seen and What is not Seen (July 1850)

Beginning the day after the Revolution, Bastiat and some younger friends started a small daily newspaper, La République française, which they distributed on the streets of Paris for an entire month.[49] On the first page of the first issue Bastiat and his friends declared their fervent republican ideals and a long list of liberal reforms they wanted to see introduced in the new Republic: the complete freedom of working, an end to state funded religion and education, an end to all taxes on food, an end to conscription into the army, and the “inviolable respect for property” (especially that form of property which was one’s own labour).[50]

This began a new phase in Bastiat’s life which was focussed on national politics (he was elected to the Constituent Assembly in April 1848 and to the Legislative Assembly in May 1849 representing his home district of Les Landes), reforming the taxation and expenditure policies of the new government (via his position as VP of the Finance Committee of the Chamber), and countering the socialist movement which had become a powerful force during the revolution.

Concerning Bastiat’s more formal political activities, we have several examples of the material Bastiat circulated to the electors in his home town and electoral district of Mugron in his efforts to get elected, firstly unsuccessfully in July 1846 with “To the Electors of the Arrondissement of Saint-Sever”[51], and then successfully to the Constituent and then the National Assembly in a “Statement of Electoral Principles” (March, 1848),[52] “Letter on the Referendum for the Election of the President of the Republic” (Aug. 1848),[53] and “Statement of Electoral Principles” (April, 1849).[54] These provide some clues to his political ideas and his program for reform. In his address “To the Electors of the Arrondissement of Saint-Sever” (July 1846) he gave a clear statement of his belief in a very limited role for government, seeing it as a dangerous living power which was constantly trying to grow in size. It was up to informed voters to make sure that it stuck to doing its proper job of “administering justice, of repressing crime, of paving roads, of repelling foreign aggression.” He also has an impassioned denunciation of French colonial policy in Algeria, calling the colonial system, whether British or French, “the most disastrous illusion ever to have led nations astray.”

In his campaign to get re-elected to the Legislative Assembly in April 1849 he reminded the Landais voters that he had served with some distinction on the Finance Committee and had opposed the socialist policies of the new government which he described as “theft regularized by law and executed through taxes.” One of his arguments to counter criticism of his voting behaviour in the Assembly was that he sometimes supported the right (on cutting taxes) and sometimes the left (on the right to form unions) depending on who best supported the principle of individual liberty at any given moment. He usually sided with the right on economic issues, and with the left on civil liberties issues. We also have a couple of formal speeches which he gave in the Assembly on cutting the tax on alcohol and the right of workers to form unions.[55] Unfortunately we do not yet have a detailed account of his activities in the Chamber’s Finance Committee (of which he was repeatedly elected Vice-President) or of his full voting record in the Chamber. We do know that he voted to reduce the tax on salt and the mailing of letters, reducing the size of the military, and abolishing conscription. We also have a couple of pamphlets he wrote on matters before the Assembly which he wanted to have circulated in print because he could not make himself heard in the Chamber because of his worsening throat condition. This included pamphlets on reducing the tax on salt (Jan. 1849), ending state subsidies to education, cutting the size of the military budget, and ending conflicts of interest in the Chamber by forbidding civil servants from also being Deputies.[56]

He briefly returned to radical street journalism while an elected Deputy in June 1848 when he, Molinari, and a few other economists created another magazine directed at ordinary people called, Jacques Bonhomme,[57] which appeared for only 4 issues before the rioting and army crackdown of the June Days forced them to close for reasons of safety. In the middle of street demonstrations in favour of socialism Bastiat and his friends were handing out their newspaper with articles calling for laissez-faire economic policies and denouncing the welfare state as “that great fiction where everybody tries to live at the expence of everybody else.”[58] The earliest version of his great essay “The State” appeared as a short article in Jacques Bonhomme and it is quite likely that it was also pasted up all over the working class areas of Paris as a wall poster or placard. Bastiat also bravely wrote and circulated leaflets calling for the immediate closing down of the National Workshops which were bankrupting the French state.[59] It was the closure of the Workshops which prompted the June Days’ rioting and its brutal suppression by the Army and National Guard, when thousands were killed or arrested. In spite of opposing the demands of the rioters, Bastiat courageously intervened when he saw soldiers firing into the crowds by arranging a cease fire and helping carry the dead and wounded into the side streets where they could be attended to.[60]

Bastiat played an important part in the anti-socialist campaign undertaken by Guillaumin and the political economists. They published a large number of pamphlets and books during 1848 and 1849 to oppose the socialists’s support for the right to work (i.e. a right to a job guaranteed by the state) which they wanted to see included in the new Constitution which was being debated by the Constituent Assembly over the summer of 1848, the National Workshops unemployment relief program established by Louis Blanc, Proudhon’s plans for a Peoples’ Bank which would issue interest free credit to workers, and the greatly expanded demands on the state’s budget to provide all manner of what we would today call policies of the modern welfare state. This is the context of Bastiat’s anti-socialist pamphlet, The State (June, Sept. 1848),[61] which would become the first of a series of 12 anti-socialist pamphlets, marketed by Guillaumin as “Mister Bastiat’s Little Pamphlets” which he wrote over the next two years. These pamphlets include Property and Law (May 1848)[62] - which was a general defence of the right to property; Individualism and Fraternity (June 1848)[63] - where he defends the idea of individualism against socialist ideas of fraternity espoused by people like Louis Blanc; Property and Plunder (July 1848)[64] - where Bastiat discusses the difference between plunder, or the appropriation of other people’s justly acquired property, and non-violent trade where services are exchanged for other services to mutual advantage including rent charged for land use; two works which point out to conservative protectionists that their ideas are very similar to that of the socialists, that it was just another form of the communism, or legal plunder, Protectionism and Communism (January 1849)[65] and Plunder and Law (May 1850);[66] and Damn Money! (April 1849) in which he warns of the dangers of paper money.[67]

One of Bastiat’s major concerns as a Deputy was to cut the size of the government’s budget by eliminating programs and reducing expenditure to an absolute minimum. This would allow the abolition or cutting of most taxes and tariffs which weighed heavily on the poor and the average worker (especially on food and drink). Since expenditure on the military was the single biggest item in the budget (30%) Bastiat wanted to see it cut massively (he advocated an immediate cut of 50%). He lobbied in the Chamber but because of his failing voice he circulated his ideas by means of a printed pamphlet Peace and Freedom or the Republican Budget (February 1849). Connected to this was the idea pushed by the leading free traders in Europe, Richard Cobden in England and Bastiat in France, to reduce international tensions by cutting tariffs and putting pressure on governments to reduce the size of their military, and to create mechanisms for the arbitration of international disputes. Both Cobden and Bastiat gave important speeches at the big Friends of Peace meeting which was held in Paris in August 1849.[68] Bastiat’s was entitled “Disarmament, Taxes, and the Influence of Political Economy on the Peace Movement” and in it he denounced conscription as a form of “military taxation” of the poor and called for “absolute non-intervention” in the affairs of other nations and for “simultaneous disarmament” of both England and France. As a result of this speech and other writings, Bastiat was likely sent on a secret government mission in October or November to London to speak with Cobden about the possibilities of a disarmament treaty between Britain and France. President Louis Napoléon’s government reshuffle in December put an end to this effort.

In spite of all the political distractions he faced, Bastiat did not neglect his more theoretical economic interests completely, although these did suffer to some degree. Because of the criticisms of socialists of the very idea of the legitimacy or profit, interest, and rent, and the near bankruptcy of the French state, Bastiat turned for the first time to monetary matters and wrote a series of pamphlets and essays such as Capital and Rent (February 1849),[69] Damn Money! (April 1849),[70] and his important and very long debate with Proudhon over the legitimacy of profit, interest, and rent, Free Credit (October 1849 - February 1850),[71] in order to address these issues.

In Capital and Rent (Feb. 1847) Bastiat defended the payment of rent against the criticism of the socialists who argued that it was unjust because it was “unearned”. He also developed in more detail his own new theory of rent. He argued that there was nothing special about rent from agricultural land, compared to other returns on capital such as profits and interest, since they were all examples of the "mutual exchange of services." Maudit argent! (Damn Money) (April 1849) is Bastiat’s most extended discussion of money. It was written to counter the growing socialist demand for government measures to solve the economic crisis which followed the February Revolution. This came in the form of two demands: for banks to issue credit at very low or zero interest rates (especially from Proudhon), and to expand the money supply in order to cover the growing government debt which was used to fund unemployment measures and other government expenditures.

Some wealthy benefactors made it possible for Bastiat to spend the summer of 1849 in the seclusion of a hunting lodge in a Paris on the outskirts of Paris so he could work full-time and without distraction on completing his economic treatise. He was thus able to get together 10 chapters for the first edition of Economic Harmonies which was published in January 1850. Many of his ideas were so new and radical, especially those on population growth, exchange as the mutual exchange of services (including rent), and his ideas on subjective value, that the book was not well received by his colleagues in the PES.

As his health continued to fail, Bastiat took a leave of absence from the Chamber and in the summer of 1850, when he had completely lost the ability to speak and was suffering excruciating pain from a lump in his throat, and travelled to Mugron and a nearby spa in order to seek some relief from his affliction and probably say goodbye to his family and friends. While in Mugron and Eaux-Bonnes he managed to finish two of his best known works, The Law (June 1850)[72] and What is Seen and What is not Seen (July 1850),[73] with the famous chapter on “The Broken Window.” The Law (June 1850) is Bastiat’s clearest statement of his view of natural law as the basis for the right to life, liberty, and property; and that individuals had the right to organise themselves in such a way as to exercise a legitimate defence of these rights, and that this was the sole legitimate function of the state. As he put it, “the law (should limit) itself ”to ensuring that all persons, freedoms, and properties were respected“ and that it should be ”merely the organization of the individual Right of legitimate defense, the obstacle, brake and punishment that opposed all forms of oppression and plunder."

Unfortunately, he believed the state kept exceeding this strict limit on its power which allowed some people to plunder the property and liberty of others. This he defined as “legal plunder” and thought it was the main cause of “the disturbiong factors” which created so many of the economic problems which plagued humanity. The pamphlet “Property and Plunder” (June 1848) is Bastiat’s most extended treatment of plunder. He had planned to write another book on “The History of Plunder” once he had finished the Economic Harmonies but did not live long enough to do so. We can get some idea of what he might have written from the fragments he has left us. There is this pamphlet, several of the anti-socialist pamphlets also deal with plunder in its various forms, as well as the first two chapters of Economic Sophisms. Series II, “The Physiology of Plunder” and “Two Moralities”.[74] Bastiat believed that human history had progressed through various stages of organised plunder, such as Slavery, Theocracy, Monopoly, and Government Exploitation, and would soon move onto Communist plunder if the socialists of 1848 could have their way.

However, Bastiat may well have left his best to the very last. His French editor Paillottet tells us that Bastiat lost the first draft of What is Seen and What is Not Seen (July 1850) when moving house, rewrote it and threw it into the fire because he was not happy with it, and then wrote it a third time, in spite of his rapidly failing health. It is a collection of 12 essays which are connected by different treatments of the same theme, namely the opportunity costs of making economic decisions, or as Bastiat phrased it the “unseen” costs. This might be one of Bastiat’s most important insights, one for which he has not had due recognition.[75] As he cleverly illustrates the principle in the opening chapter on “The Broken Window”, what the poor shopkeeper Jacques Bonhomme has to spend on replacing his broken window is money he could have spent on something else. He thus loses twice because he has lost a capital good (the window) as well as being prevented from making another purchase he might have preferred to make had his window not been broken by his hooligan son.[76] Bastiat applies this important insight to such topics as dismissing large numbers of the armed forces and its impact on garrison towns, the state funding of theaters, government subsidies to colonists going to Algeria, and so on. He concluded the book, and perhaps his life since he was to die not long after this was published, that “not to know Political Economy is to let oneself be be blinded by the immediate effect of a phenomenon; to know Political Economy is to take into consideration all the effects, both immediate and future.”

A brief discussion of his unfinished magnum opus on Social and Economic Harmonies and Disharmonies will be provided in the next section.

In this final, all too brief period of Bastiat’s life, we see him move from being an almost full-time agitator for free trade to being a revolutionary street journalist, an elected politician, an expert on Government financial affairs, an anti-socialist pamphleteer, a peace campaigner, and a very determined man who wanted to finish his last work before he died.

Endnotes-

La République française. A daily journal. Signed by the editors: F. Bastiat, Hippolyte Castille, Gustave de Molinari. It appeared from 26 February to 28 March in 30 issues. ↩

-

T.186 "A Few Words about the Title of our Journal" La République française, (26 February 1848), in CW3, pp. 524–26. ↩

-

T.71 “To the Electors of the Arrondissement of Saint-Sever (Mugron, July 1, 1846)”, CW1, pp. 352–67. ↩

-

T.206 “Statement of Electoral Principles. To the Electors of Les Landes, 22 March, 1848,” CW1, p. 387. ↩

-

T.221 “Letter on the Referendum for the President of the Republic,” 13 August 1848, CW1, pp. 395–96. ↩

-

T.238 “Statement of Electoral Principles in April 1849,” CW1, pp. 390–95. ↩

-

T.243 "Speech on The Repression of Industrial Unions“ (17 November 1849), CW2, pp. 348–61; T.244 ”Speech on the Tax on Wines and Spirits" (12 December 1849), CW2, pp. 328–47. ↩

-

T.232 “The Consequences of the Reduction in the Salt Tax” (Jan. 1849), CW2, pp. 324–27; on state education, T.254 “Reflections on the Amendment of M. Mortimer-Ternaux” (1 April 1850), CW2, 362–65, and T.247 “Baccalaureate and Socialism” (early 1850), CW2, pp. 185–234; T.235 “Peace and Freedom or the Republican Budget” (February 1849), CW2, pp. 282–327; T.236 “Parliamentary Conflicts of Interest” (March 1849), CW2, pp. 366–400. ↩

-

Jacques Bonhomme. Editor J. Lobet. Founded by Bastiat with Gustave de Molinari, Charles Coquelin, Alcide Fonteyraud, and Joseph Garnier. It appeared approximately weekly with 4 issues between 11 June to 13 July; with a break between 24 June and 9 July because of the rioting during the June Days uprising. See "Bastiat’s Revolutionary Magazines," in Appendix 6, in CW3, pp. 520–22. ↩

-

T.214 "Laissez-Faire", Jacques Bonhomme, 11–15 June 1848, CW1, pp. 434–45; T.212 “The State”, Jacques Bonhomme, 11–15 juin 1848, CW2, pp. 105–6. ↩

-

T.219 “To Citizens Lamartine and Ledru-Rollin”, Jacques Bonhomme, 20–23 June 1848, CW1, pp. 444–45. ↩

-

This was the second time Bastiat got caught in the cross-fire during the 1848 Revolution. The first occasion was in February and then again in June. See, Letter 93 to Marie-Julienne Badbedat (Mme Marsan), 27 February 1848, [CW1, pp. 142–43]/titles/2393#lf1573–01_head_119); and Letter 104 to Julie Marsan (Mme Affre), Paris, 29 June 1848, CW1, pp. 156–57. ↩

-

This was an expanded version of his article from June 1848. T.222 “The State” (25 September 1848), CW2, pp. 93–104. See also, "Bastiat's Anti-Socialist Pamphlets" in Further Aspects of Bastiat's Thought, CW4 (forthcoming). ↩

-

T.208 “Property and Law,” JDE, 15 May 1848, CW2, pp. 43–59. ↩

-

T.209 “Individualism and Fraternity” (June 1848), CW2, pp. 82–92. ↩

-

T.220 “Property and Plunder,” Journal des débats, 24 July 1848, CW2, pp. 147–84. ↩

-

T.231 “Protectionism and Communism” (January 1849), CW2, pp. 235–65. ↩

-

T.257 “Plunder and Law”, Journal des Économistes, 15 May 1850, CW2, pp. 266–76. ↩

-

T.239 “Damned Money!” Journal des Économistes, 15 April 1849, in CW4 (forthcoming). ↩

-

Frédéric Bastiat’s Speech (T.240) on “Disarmament, Taxes, and the Influence of Political Economy on the Peace Movement”, pp. 49–52, in Report of the Proceedings of the Second General Peace Congress, held in Paris, on the 22nd, 23rd and 24th of August, 1849. Compiled from Authentic Documents, under the Superintendence of the Peace Congress Committee. (London: Charles Gilpin, 5, Bishopsgate Street Without, 1849), pp. 49–52; in Addendum: Additional Material by Bastiat, CW3, pp. 514–20. ↩

-

T.234 Capitale et rente (Paris: Guillaumin, 1849), in CW4 (forthcoming). ↩

-

T.239 “Damned Money”, Journal des Économistes, 15 April 1849, in CW4 (forthcoming). ↩

-

T.241 Gratuité du crédit. Discussion entre M. Fr. Bastiat et M. Proudhon (Free Credit. A Discussion between M. Fr. Bastiat and M. Proudhon) (Paris: Guillaumin, 1850) in CW4 (forthcoming). ↩

-

T.258 La Loi, par M. F. Bastiat. Membre correspondant de l'Institut. Représentant du peuple à l'Assemblée Nationale (Paris: Guillaumin, 1850). In CW2, pp. 107–46. ↩

-

T.259 Bastiat, Ce qu’on voit et ce qu’on ne voit pas, ou l’Économie politique en une leçon. Par M. F. Bastiat, Représentant du peuple à l’Assemblée nationale, Membre correspondant de l’Institut (Paris: Guillaumin, 1850), in CW3, pp. 401–52. FEE ed.](/titles/bastiat-selected-essays-on-political-economy#lf0181_label_033) ↩

-

T.161 ES2.1 "Physiologie de la Spoliation" (The Physiology of Plunder) and ES2.2 "Deux morales" (Two Moral Philosophies) in CW3 (in production). FEE ed. ↩

-

Anthony de Jasay believes this insight is original to Bastiat and is his main contribution to the development of economic science. Jasay wrote a two part article called “The Seen and the Unseen” which appeared on the Econlib website in December 2004 and January 2005 where he applies Bastiat’s idea and borrows the name for his own title. See https://www.econlib.org/library/Columns/y2004/Jasayunseen.html. He makes explicit reference to the greatness of Bastiat as an economist in the second article he wrote for Econlib, “Thirty-five Hours” (July 15, 2002) https://www.econlib.org/library/Columns/Jasaywork.html and credits him for inventing the idea of “opportunity cost”: “he anticipated the concept of opportunity cost and was, to my knowledge, the first economist ever to use and explain it.” See David M. Hart, "Negative Railways, Turtle Soup, talking Pencils, and House owning Dogs: "The French Connection" and the Popularization of Economics from Say to Jasay," (Sept. 2014) . A shortened version of this paper was published in the "Symposium on Anthony de Jasay" in The Independent Review, vol. 20, no. 1, Summer 2015, "Broken Windows and House-Owning Dogs: The French Connection and the Popularization of Economics from Bastiat to Jasay," pp. 61–84. ↩

-

See, T.259 WSWNS 1 “The Broken Window,” in CW3, pp. 405–7; and T.128 ES3 4 “One Profit versus Two Losses” (LE, 9 May, 1847), in CW3, pp. 271–76, in which Bastiat discusses what he termed “the double incidence of loss.” ↩

Correspondence↩

Letter 91. Paris, 25 Feb. 1848. To Richard Cobden↩

SourceLetter 91. Paris, 25 Feb. 1848. To Richard Cobden (OC1, pp. 168-70) [CW1, pp. 139-41].

TextMy dear Cobden, you already know our news. Yesterday we were a monarchy and today we are a republic.201

[140]I have not the time to tell you about it, I simply want to put before you a point of view of the utmost importance.

France wants and needs peace. Her expenses are going to increase, her income to decrease, and her budget is already in deficit. She therefore needs peace and a reduction in her military undertakings.

Without this reduction no serious savings are possible, and therefore no financial reform and no abolition of odious taxes. And without these, the revolution will fall out of favor.

But France, as you will understand, cannot take the initiative of disarming. It would be absurd to ask her to do so.

You see the consequences. Because she does not disarm, she cannot reform anything; and because she does not reform anything, she will be killed by her finances.

The sole fact that foreigners are retaining their forces is obliging us to perish. But we do not wish to perish. Therefore, if foreign nations do not put us in a position to disarm by disarming themselves, if we have to keep three or four hundred thousand men in a state of readiness, we will be drawn into a war of words. This is inevitable. For in this case, the only means of being able to draw breath here would be to create embarrassment for all the kings of Europe.

If, therefore, foreigners understand our situation and its dangers, they will not hesitate to give us this proof of confidence by disarming significantly. In this way, they will put us in a position to do likewise, rebuild our finances, relieve the people, and accomplish the work which has been thrust upon us.

If, on the other hand, foreigners consider it prudent to remain armed, I do not hesitate to say that this so-called prudence is the greatest imprudence, since it will reduce us to the extremity which I have already mentioned.

Please heaven that England understands this and makes it understood. It would save the future of Europe. If she follows the traditions of old-style politics, I challenge you to tell me how we can escape the consequences.

Think carefully about this letter, dear Cobden, and weigh all its statements. See for yourself whether everything I have said to you is not inevitable.

If you remain armed, we will remain armed with no evil intentions. But because we remain armed, we will be overcome by the weight of unpopular taxes. No government could survive this. Governments can change as much as they like. Each will encounter the same problem and the day will come [141] when it will be said, “Since we cannot send the soldiers back to their homes, we will have to dispatch them to arouse the people.”

If you disarm to a significant extent and if you unite closely with us to advise Prussia to follow the same policy, under these conditions a new era may and will spring into being on 24 February.

Letter 92. Paris, 26 Feb. 1848. To Richard Cobden↩

SourceLetter 92. Paris, 26 Feb. 1848. To Richard Cobden (OC1, pp. 170-71) [CW1, pp. 141-42].

TextMy dear Cobden, I would give a great deal of money (if I had it) to have M. de Lamartine as our minister of foreign affairs for a moment. But I cannot reach him.

I wanted to go to London, but not without having seen him, since I need to submit to him the ideas I have to communicate to you.

England can do an immense amount of good without damaging herself in the slightest. She can replace France’s disastrous prejudices with a sincere affection. She has only to will this. For example, why does she not quite freely abandon her veiled opposition to our sad conquest of Algeria? Why does she not quite freely abandon the dangers arising from the right of inspection?202 Why does she allow the idea that she wishes to humiliate us to take root here? Why wait for events to poison these matters? What a magnificent spectacle it would be if England said: “When France has chosen a government, England will make haste to recognize it, and as proof of her friendship she will also recognize Algeria as French and renounce the right of inspection, of which she moreover acknowledges the ineffectualness and drawbacks!”

Tell me, my dear Cobden, what would such acts cost your country if they were freely carried out as I describe?

Over here, we cannot divest ourselves of the idea held by the French that the English covet Algeria. This is absurd, but this is how it appears.

We cannot efface from people’s minds that the right to inspect is part of your policy. This is also absurd, but this is how it appears.

In the name of peace and humanity, bring about these great measures! Let us carry out popular diplomatic policies and let us do it in good time.

[142]Write to me. Tell me frankly if a journey to London with this in mind, under the auspices of M. de Lamartine, would have any chance of bringing about a result. I will show him your letter.

Letter 93. Paris, 27 Feb. 1848. To Madame Marsan↩

SourceLetter 93. Paris, 27 Feb. 1848. To Madame Marsan (Marie-Julienne Badbedat) (JCPD) [CW1, pp. 141-42].

TextYou must be anxious. I would like to reassure you. My cold has almost disappeared and in this respect I am in my normal state, with which you are familiar. On the other hand, the revolution has left me safe and sound.

As you will see in the newspapers, on the 23rd everything seemed to be over. Paris had a festive air; everything was illuminated. A huge gathering moved along the boulevards singing. Flags were adorned with flowers and ribbons. When they reached the Hôtel des Capucines, the soldiers blocked their path and fired a round of musket fire at point-blank range into the crowd. I leave you to imagine the sight offered by a crowd of thirty thousand men, women, and children fleeing from the bullets, the shots, and those who fell.203

An instinctive feeling prevented me from fleeing as well, and when it was all over I was on the site of a massacre with five or six workmen, facing about sixty dead and dying people. The soldiers appeared stupefied. I begged the officer to have the corpses and wounded moved in order to have the latter cared for and to avoid having the former used as flags by the people when they returned, but he had lost his head.

The workers and I then began to move the unfortunate victims onto the pavement, as doors refused to open. At last, seeing the fruitlessness of our efforts, I withdrew. But the people returned and carried the corpses to the outlying districts, and a hue and cry was heard all through the night. The following morning, as though by magic, two thousand barricades made the insurrection fearsome. Fortunately, as the troop did not wish to fire on the National Guard, the day was not as bloody as might have been expected.

All is now over. The Republic has been proclaimed. You know that this is good news for me. The people will govern themselves. I am convinced that for a long time they will govern themselves badly, but they will learn from [143] experience. Right now, ideas I do not share have the upper hand. It is fashionable to expand the functions of the state considerably, and I think they should be restricted. For this reason, I am outside the movement, although several of my friends are very powerful in it. Two friends and I produced a leaflet to inject some of our ideas into the intellectual to and fro.204

Do not worry about the sequel. My age and health have extinguished in me any taste for street campaigning. As for a situation, I will not be seeking one, and will wait until I am considered useful.

I am writing you just a hasty note. I still have repose in view, since age and duties are piling up.

Julie is not giving me as good news as I would like.

Please ask her to write to me from time to time. I embrace both her and her children warmly.

Letter 94. Paris, 29 Feb. 1848. To Félix Coudroy↩

SourceLetter 94. Paris, 29 Feb. 1848. To Félix Coudroy (OC1, pp. 80-82) [CW1, pp. 143-45].

TextMy dear Félix, in spite of the shabby and ridiculous conditions you have been given, I will wholeheartedly congratulate you if you reach a settlement. We are getting old; a little peace and tranquillity in our later years is the happy condition to which we should lay claim.

Since, dear friend, I cannot give you either consolation or advice on this sad outcome, you will not be surprised if I immediately tell you about the major events which have just occurred.

The February revolution has certainly been more heroic than that of July.205 There is nothing so admirable as the courage, order, calm, and moderation of the people of Paris. But what will the results be? For the last ten years, false doctrines that were much in fashion nurtured the illusions of the working classes. They are now convinced that the state is obliged to provide bread, work, and education to all. The provisional government has made a solemn promise to do so; it will therefore be obliged to increase taxes to endeavor to keep this promise, and in spite of this it will not keep it. I have no need to tell you what kind of future lies ahead of us.

[144]There is one possible recourse, which is to combat the error itself, but this task is so unpopular that it cannot be carried out safely; I am, nevertheless, determined to devote myself to this if the country sends me to the National Assembly.

It is clear that all these promises will succeed in ruining the provinces to satisfy the population of Paris, since the government will never undertake to feed all the sharecroppers, workers, and craftsmen in the départements and, above all, in the countryside. If our country understands the situation, I say frankly that she will elect me; if not, I will carry out my duty with greater safety as a simple writer.

The scramble for office has started, and several of my friends are very powerfully placed. Some of them ought to understand that my special studies may be useful, but I do not hear them mentioned. As for me, I will set foot in the town hall only as an interested spectator; I will gaze on the greasy pole but not climb it. Poor people! How much disillusionment is in store for them! It would have been so simple and so just to ease their burden by decreasing taxes; they want to achieve this through the plentiful bounty of the state and they cannot see that the whole mechanism consists in taking away ten to give it back eight, not to mention the true freedom that will be destroyed in the operation!

I have tried to get these ideas out into the street through a short-lived journal206 which was produced in response to the situation; would you believe that the printing workers themselves discuss and disapprove of the enterprise? They call it counterrevolutionary.

How, oh how can we combat a school which has strength on its side and which promises perfect happiness to everyone?

My friend, if someone said to me, “You will have your idea accepted today but tomorrow you will die in obscurity,” I would agree to it without hesitation, but striving without good fortune and without even being listened to is a thankless task!

What is more, as order and confidence are the supreme aims at present, so we must refrain from any criticism and support the provisional government at all cost, making allowances even for its errors. This is a duty that obliges me to make an infinite number of allowances.

Farewell, the elections will take place shortly, and we will see what happens [145] then. In the meantime, let me know if you come across any attitudes favorable to me.

Letter 95. Paris, 4 March 1848. To M. Domenger, in Mugron↩

SourceLetter 95. Paris, 4 March 1848. To M. Domenger, in Mugron (OC7, pp. 385-86) [CW1, pp. 145-46].

TextYou are quite right to remain calm. Apart from the fact that we will all need it, the tempest would need to howl furiously before it was felt in Mugron. Up to now, Paris is enjoying the most perfect peace, and this spectacle is in my view just as imposing in its way as courage in battle. We have just witnessed the funeral ceremony.207 I think that the entire universe was out in the street. I have never seen so many people. I have to say that the population appeared to be friendly but cold. Nothing can bring it to utter cries of enthusiasm. This is perhaps all to the good and appears to prove that time and experience have matured us. Are not unbridled demonstrations something of an obstacle to the proper management of affairs?

The political aspect of the future is not being given much attention. It seems that universal suffrage and other rights of the people are so unanimously agreed upon that they are given no further thought. But what is darkening our prospects are economic matters. In this respect, ignorance is so profound and widespread that severe experiences are to be feared. The idea that there is a scheme yet unknown but easy to find, which is bound to ensure the well-being of all by reducing work, is the dominant theme. As it is adorned with such fine terms as fraternity, generosity, etc., no one dares attack these wild illusions. Besides, no one would know how to do so. People instinctively fear the consequences which may arise from the exaggerated hopes of the working classes, but between this and being in a position to determine the truth there is a wide gap. For my part, I continue to think that the fate of the workers depends on the speed with which capital is built up. Anything that can, directly or indirectly, damage property, undermine confidence, or weaken security is an obstacle to the accumulation of capital and has an unfavorable effect on the working classes. This is also true for all taxes and irritating governmental interference. What should we therefore [146] think of the systems in fashion today which have all these disadvantages at once? As a writer, or in another capacity, if my fellow citizens call upon me, I will defend my principles to the last. The current revolution is not changing them any more than it is changing my behavior.

Let us say no more about the statements attributed to F——. This is far behind us. Frankly this meretricious program could not be sustained. I hope that people will be satisfied with the choices made in our département. Lefranc is a courageous and honest Republican who is incapable of making life difficult for anyone without serious and just reasons.

Letter 96. Mugron, 5 Apr. 1848. To Richard Cobden↩

SourceLetter 96. Mugron, 5 Apr. 1848. To Richard Cobden (OC1, pp. 171-731) [CW1, pp. 146-47].

TextMy dear friend, here I am, all alone. Why can I not bury myself here forever and work peacefully on the economic synthesis208 I have in my head and which will never leave it! For, unless there is a change in public opinion, I am going to be sent to Paris with the responsibility of the awe-inspiring mandate of a representative of the people. If I had health and strength, I would accept this mission with enthusiasm. But what can my weak voice and my sickly and nervous constitution do in the midst of the revolutionary whirlwind? How much wiser it would have been to devote my final days to examining in silence the great problem of society and what the future holds in store for it, especially since something tells me that I would have found the answer. Poor village, the humble dwelling of my fathers, I am about to bid you an eternal farewell; I am going to leave you with the foreboding that my name and life, lost in the midst of storms, will not have even the modest usefulness for which you prepared me!

My friend, I am too far from the theater of events to tell you about them. You will learn about them before I do, and at the time I am writing to you, it may be that the facts on which I might base my reasoning are past history. If the overthrown government had left us finances in good order, I would have total faith in the future of the Republic. Unfortunately the treasury has been destroyed and I know enough about the history of our first revolution to realize the influence of financial chaos on events. An urgent measure leads to an arbitrary one, and it is above all in this situation that fate [147] exercises its power. At present, the people are behaving admirably, and you would be surprised to see how well universal suffrage is working right from the start. But what will happen when taxes, instead of decreasing, increase, when there is a shortage of jobs, and when bitter reality succeeds brilliant hopes? I had perceived a lifeline, on which it is true I scarcely placed much hope, since it presupposed wisdom and prudence in kings; this was the simultaneous disarmament of Europe. If this happened, finances would have been restructured everywhere, nations relieved and restored to order, industry would have developed, the number of jobs increased, and peoples would have waited calmly for the gradual development of administrative institutions. Monarchs, however, have preferred to stake their all or rather they were unable to assess present or future situations. They are pressing against a spring, without understanding that as their strength weakens that of the spring increases proportionately.

Imagine that they had disarmed everywhere and reduced taxes accordingly, and had, also, given to their nations institutions that are, moreover, not to be gainsaid. France, burdened with debt, would make haste to do likewise, only too happy to be able to found the Republic on the solid basis of a genuine relief of the burden on the people. Peace and progress would go hand in hand. However, the opposite has happened. People are arming everywhere, public expenditure (and taxes and hindrances) is increasing everywhere, when the taxes that exist are precisely what is causing revolutions. Will not all of this end in a terrible explosion?

What is wrong? Is justice so difficult to exercise and prudence so difficult to understand?

Since my arrival here, I have not seen an English newspaper. I do not know what is happening in your Parliament. I would have hoped that England would take the initiative in rational politics and would take it with the energetic boldness which she has shown so often in the past. I would have hoped that she would want to teach mankind how to live,209 by disarming, abandoning expensive colonies, ceasing threatening behavior, protecting herself from any possibility of being threatened, removing unpopular taxes, and presenting the world with a fine spectacle of union, strength, wisdom, justice, and security. But, alas! Political economy has not yet sufficiently pervaded the masses, even in your country.

Letter 97. Mugron, 12 Apr. 1848. To Horace Say↩

SourceLetter 97. Mugron, 12 Apr. 1848. To Horace Say (OC7, pp. 381-82) [CW1, pp. 148-49].

TextMy dear friend, I constantly look for your name in the newspapers, but they are not yet discussing the elections. They are probably too busy reporting on the political clubs. This is the only explanation I can give of the silence of the Paris press. Perhaps Paris is too stormy a theater, given your character and the life you are used to. I now regret that you have not considered moving to one of the départements. Socialist folly has whipped up such terror that because of your well-known antecedents you would have had wonderful opportunities there. Your candidature has the advantage of giving you the opportunity of putting about sane ideas. This is a great deal but not enough for our cause. For this reason, make a supreme effort, abandon your customary reserve for a few days, start something of a campaign, and leave no stone unturned to enter the Constituent Assembly. I sincerely believe that the salvation of the country depends on our principles gaining a majority.

If there is no change in public opinion here, my election is assured. I even think that I will gain all the votes except for those of a few traders in resin who are terrified of free trade.

All the committees210 in the cantons support me.

Next Sunday, we will be having a general central meeting. I would have to make a huge mess of things to change the attitudes of electors toward me.

A very strange fact is the ignorance of socialist doctrines of the people in this country. There is a horror of communism. But communism is seen only as the sharing out of land. Last Sunday, during a large public meeting, a general murmur arose when I said that communism was not a threat in this respect. People seemed to deduce from these words that I was only very tepidly opposed to this form of communism. The rest of my speech removed this impression. It is really very dangerous to speak before an audience that is so little informed. You risk not being understood. . . .

I must admit to you that I am very worried about the future. How can industry revive when it is accepted in principle that the scope for regulation [149] is unlimited? When every minute a decree on earnings, working hours, the cost of things, etc., can upset all economic decision making?

Farewell, my dear M. Say. Please remember me to Mme Say and M. Léon.

P.S. The central meeting of delegates took place yesterday; I do not know why it was brought forward. After answering questions, I withdrew and this morning learned that I have all of the votes except two. Having forgotten to post my letter before leaving, I have opened it to tell you this result which may please you. Try to make a supreme effort, my dear friend, to ensure that political economy, which is lifeless in the Collège de France,211 is represented in the Chamber by M. Say. Shame to the country, if it excludes a name of this eminence that is so nobly borne!

Letter 98. Paris, 11 May 1848. To Richard Cobden↩

SourceLetter 98. Paris, 11 May 1848. To Richard Cobden (OC1, pp. 173-74) [CW1, pp. 149-50].

TextIn the meantime, I will go straight to the subject of my letter.

You know that a workers’ commission used to meet at the Luxembourg Palace under the chairmanship of M. Louis Blanc. The presence of the National Assembly dispersed it, but it was quick to set up a commission responsible for carrying out an inquiry on the situation of industrial and agricultural workers and suggest ways of improving their lot.

This is a huge task, which the current illusions are making very hazardous.

I have been called upon to take part in this commission. I was fairly nominated, [150] after I set out my doctrines frankly, but above all from the point of view of property rights. I am having printed what I said, which succeeded in having me nominated, in an article entitled Property and Law, which will be appearing in the next issue of Le Journal des économistes. Please read it.212

I now want to use this inquiry to bring truth out into the open. Whether I am right or wrong, we need the truth. In France, we do not have much experience of the machinery known as a parliamentary inquiry. Do you know of any work which describes the art of organizing these inquiries so as to reveal the truth? If you know of one, please let me know, or better still send it to me.

Anti-British prejudices are still far from being extinguished here. People think that the English are devoting themselves on the continent to countering the republican policy of France and I would not put this past your aristocracy. For this reason, I will be following with great interest your new campaign in favor of political and economic reform, which may reduce the foreign influence of the squirearchy.213

Letter 99. abc↩

SourceLetter 99. Paris, 17 May 1848. To Madame Schwabe (OC7, pp. 421-23) [CW1, pp. 150-51].

TextYou must think me a very badly brought up Frenchman to have taken so long to thank you and your husband for the many gestures of affection you both showered on me during your stay in Paris. I certainly have not forgotten them. The memory of them will never be effaced from my heart, but you know that I made a journey to the Pyrenees I hold so dear. What is more, I did not know where to address my letters; this one will be sent in the hope it will be lucky.

The National Assembly has met. What will come out of this blazing furnace? Peace or war? Fortune or misfortune for the human race? Up to now, it has been like a child who stutters before speaking. Can you imagine a hall as big as the Place de la Concorde? In it, there are nine hundred members debating and three thousand onlookers. To have the opportunity of making yourself heard and understood, you have to utter high-pitched shouts accompanied by very emphatic hand movements, which rapidly result in an outburst of unreasonable fury in whoever is speaking. That is how we are conducting our internal proceedings. This takes up a lot of time and [151] the general public does not have the common sense to understand that this waste of time is inevitable.

You will have learned from the newspapers of the events of the 15th. The Assembly was invaded by a horde of the populace. The pretext was a demonstration in favor of Poland. For four hours, these people endeavored to wrest from us the most subversive votes. The Assembly bore this tempest calmly, and to do justice to our population and our century I have to say that we cannot complain of any personal violence. The result of this outrage has been to make known the wishes of the entire country. It enables the executive power to take prudent measures to which it cannot have recourse if there is no provocation. It is very fortunate that things were taken so far. Without this, the aims of the seditionists would never have been so clearly seen. Their hypocrisy brought them followers. They no longer have any; they have been unmasked, and once again the finger of Providence has been seen. There were ten thousand chances that things would not turn out so well.

I assume you are calling on Mrs. Cobden. Please convey to her the admiration I feel for her, following all you have said about her.

Farewell, dear lady. Can you not give me some hope of seeing you again? Your children do not know enough French and one of your daughters is a citizen of the Republic.214 She must be made to breathe the air of her fatherland.

I shake the hand of Mr. Schwabe with great affection.

Letter 100. Paris, 27 May 1848. To Richard Cobden↩

SourceLetter 100. Paris, 27 May 1848. To Richard Cobden (OC1, pp. 175-76) [CW1, pp. 151-52].

TextMy dear Cobden, thank you for having given me the opportunity of making the acquaintance of Mr. Baines.215 I regret only having had just an instant to talk to such a distinguished man.