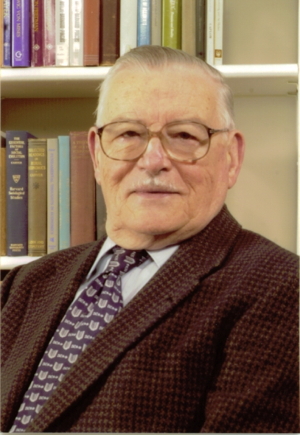

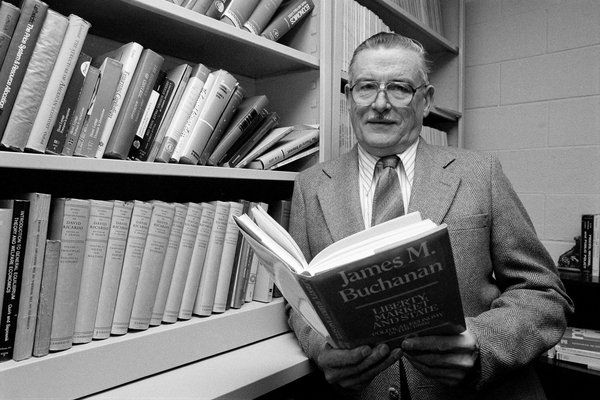

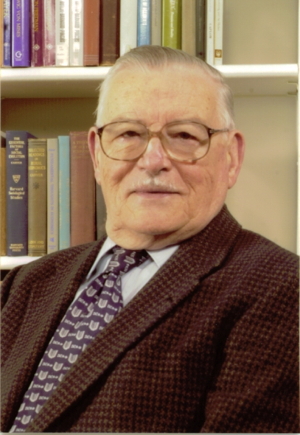

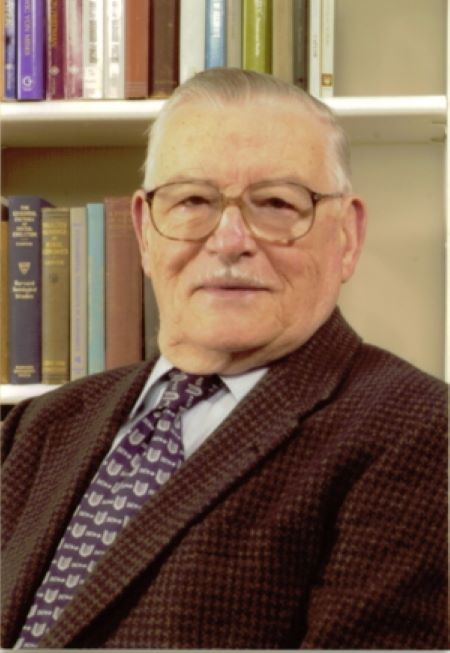

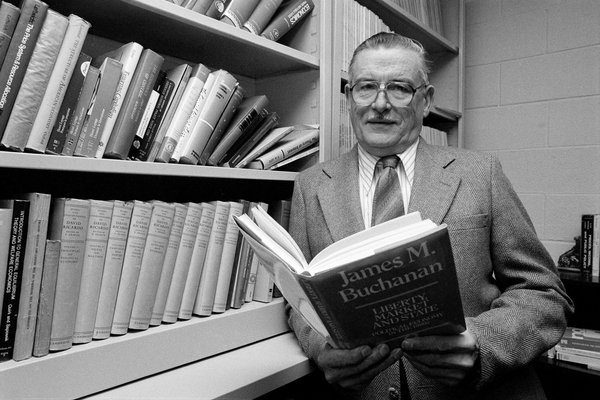

After James M. Buchanan died in 2013, a range of scholars commemorated his work in a series of essays and responses. They highlight Buchanan's Nobel Prize winning work exploring his ideas on public choice (or, theories of political failure), contractarianism, and constitutionalism as well as his personal commitment to classical liberalism. In a Buchananian spirit of fearless inquiry, they question it all - including Buchanan himself.

Lead Essay James Buchanan and the Economics of Anarchy

It is one of the features of an intellectual’s work that it has a life independent of – and possibly more extensive than -- its creator. In that sense, Jim Buchanan’s death (“after a short illness”) on January 9 is of no particular academic significance – beyond the fact that Jim himself is no longer around to correct misinterpretations of the Buchanan position (as he saw it).[1] On the other hand, it would be unseemly for the occasion to go unmarked. At the very least, Buchanan’s death provides an opportunity to restate and re-assess the “Buchanan position” (at least as I see it); and such restatement and reassessment is my purpose here.

1. a specification of the proper domains of market and political operation (which entails, in particular, limits on the domain of political decision-making). The notion that it might be left to in-period political processes to determine their own sphere of activities struck Buchanan as totally inconsistent with the constitutional logic. Limited government is the sine qua non of the constitutional approach;

2. a specification of how in-period politics is to operate. The most familiar illustration of this latter concern is, of course, the determination – in the Calculus of Consent, written with Gordon Tullock – of the “optimal decision rule” (or rules more accurately, since different kinds of decisions would predictably call for more or less inclusive majorities). Of course, the Calculus contains many other interesting arguments -- about bicameralism and the separation of powers, and fascinating suggestions about the role of institutions that are not strictly either markets or political processes, but something else – institutions of “civil society” perhaps. But the issue that most readers take away from the Calculus is that of whether simple majority rule would be the “appropriate” rule for collective decisions – with “appropriate” here taken to mean “unanimously chosen at the constitutional level.”

1. Buchanan as a Classical Liberal: Buchanan is a self-declared classical liberal. By this, I take it that he means that he places a high value on liberty (understood as something like “noncoercive social relations”) and that he is a minimalist about the appropriate role of governments. His Public Choice analysis can clearly be viewed as providing the reasoned grounds for that minimalism, as his description of Public Choice theory as the “theory of political failure” suggests. Yet he is an unusual classical liberal. For one thing, whereas most classical liberals take as their point of departure some kind of conception of the individual’s moral rights and derive their conception of liberty in terms of rights violations (or coercion), Buchanan’s normative point of departure is in the intrinsically collective exercise of jointly working out the rules of the social/economic/political game to which citizens are to be subject. In that latter exercise all individuals hold a virtually complete right of veto over what those rules will be (including the specification of the personal and property rights that the individuals will possess and be subject to). Many libertarians have thought that this collectivist point of departure is inconsistent with true liberal individualism. Buchanan was insistent that social outcomes are not chosen because they are efficient (or fair) – they are efficient (or fair) because they are chosen (in the appropriate unanimous setting). In that sense, the foundational liberal element is embodied in the fact of unanimous constitutional choice – whatever the outcome of that choice process may turn out to be.

Buchanan was an unusual classical liberal in other ways. He believed rather passionately in confiscatory estate and gift duties: He reckoned that inherited wealth (though not self-made or first-generation wealth) violates basic equality of opportunity, and his enmity towards dynasties was notable. Hence the antipathy to John F. Kennedy mentioned in footnote 12. Buchanan though Papa Joe had bought the White House for his boys, and it infuriated him. However, one might think that individual sovereignty should extend to gifts and bequests, and that totally confiscatory gift/estate duties are unlikely to emerge from unanimously approved political rules.

2. The Double Role of Exchange: A related aspect of the Buchanan construction is the double work that the notion of exchange plays. At one level, individuals behind the veil of ignorance will predictably assess alternative institutions according to the mutual gains those institutions give rise: Clearly, certain basic facts about the operation of markets and the operation of democratic politics under various specifications will predictably be taken into account by the constitutional contractors. And it is specifically the role of economics (and Public Choice analysis as part of that enterprise) to reveal those facts in relation both to markets and to democratic political process. But within Buchanan’s scheme the ultimate exercise of “exchange” occurs in and through the constitutional contract itself, and the ultimate test of markets and politics lies in the constitutional endorsement they receive. In this way, the determination of the truth of claims about markets and/or of Public Choice seems to be assigned to the judgment of actual constitutional contractors. Buchanan could sometimes make such subjectivist gestures towards truth claims; but it seems bizarre to allow claims about the exchange properties of markets (say) to be determined by constitutional contract.

3. Market Operations: In the late afternoon of his life, Buchanan became intrigued by the significance of “increasing returns” in the operation of markets. In essence, this involved a recapturing of Adam Smith’s account of the fundamental forces making for the wealth of nations and recognizing its distinctiveness (as say from Ricardo and the modern mainstream tradition). One notable feature of this work is its “objectivist” qualities, that is, the “general opulence” distributed across all classes of society that was the explanandum for Smith is an externally observable phenomenon – a brute fact about human progress and not something that exists merely in the mind of the observer/evaluator.

4. The Supply of Versus the Demand for Rules: It is one thing to establish the “reason for rules,” and even what rules agents might choose in the hypothetical constitutional setting, and another entirely to explain how those rules will be enforced at the in-period level. As Jeremy Bentham famously put it in relation to rights, the demand for rules are no more rules than hunger is bread. In the treatment in the Calculus, where the agenda is to discuss modest modifications of rules that are already in play (the size of the majority), the assumption that the modifications will be enforced can be carried perhaps by the uncontestable fact that simple majority rule seems to be pretty robust. But as the agenda is generalized to include the entire template for rules governing social and political and economic life, the problem becomes acute. It needs to be explained just why agents who know their positions and who are presumed to be predominantly self-interested will find it in their interests to enforce and/or comply with the provisions previously agreed. To the extent that we look to courts to make decisions on the rules, and to the police to enforce court decisions, do we not need a “theory of legal failure,” alongside market failure and political failure, to sustain the entire project? Buchanan seems to have had a blind spot about this issue. But without some response to the quis custodet ipsos custodes challenge, it is by no means clear that the whole elegant intellectual edifice can get off the ground. And to the extent that the necessary response involves some modification of the extreme homo economicus motivational hypothesis, may we not be required to carry that modification into the analysis of markets and in-period politics on exactly the same generality grounds that Public Choice mounts its attack on the benevolent despot?

5. Chosen versus Inherited Rules? It is a critical feature of Buchanan’s constitutional paradigm that citizens choose the rules by which they are to live: Those rules have to be products of explicit consent. That fact explains why the market is an “efficient” institution only to the extent that it is constitutionally endorsed. Many observers (including F. A. Hayek and in another sense David Hume) are inclined to respect “evolved rules” in themselves and to doubt the intellectual pretension that Buchanan’s kind of constitutional constructivism involves. Buchanan himself explicitly rejects that kind of “respect”: He thought it invokes a kind of quietism towards the institutional status quo that is ultimately servile. Middle ground is presumably available here – but one would certainly want some principled way of discerning which established rules ought to be treated with piety and which ought to be interrogated and perhaps ruthlessly overturned. There may be a tension between American vigor and European traditionalism in play here.

6. Expressive Constitutionalism? I cannot forbear to mention, by way of conclusion, an anxiety that arises out of work of my own on voting.[13] That work is an extension of the idea of rational ignorance attributable to Anthony Downs in the sense that it takes as its point of departure the asymptotic irrelevance of each individual voter in determining the electoral outcome. This means that the relation between interests and behavior has a character in markets quite different from that in the ballot box. The individual voter is subject to a veil of insignificance not unlike the Rawlsian/Buchanan veil of ignorance, in that agents are distanced from their interests by the circumstances of choice. This fact very much blunts the distinction Buchanan draws between constitutional and in-period levels of choice in two senses: first because interests are attenuated in both settings; and second because individuals are in a large-number setting in making their constitutional agreements and hence a significant element of expressive behavior is likely to enter at the constitutional level. That is, people can quite rationally “cheer” for democracy or “trial by jury” or whatever, even when such institutions would not deliver better outcomes for them. This is not just a matter of rational ignorance – though there will predictably be plenty of that. It is also a matter of giving rational assent to all kinds of nostrums that “have strong expressive appeal” even when one knows they are silly or worse. Consider for example the vast extension of “rights” that seem characteristic of most modern (popularly endorsed) constitutions.

ADDITIONAL READING

- Vol. 2.(Public Principles of Public Debt: A Defense and Restatement <oll2.libertyfund.org/titles/279>

- Vol. 3. The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy <oll2.libertyfund.org/titles/1063>

- Vol. 4. Public Finance in Democratic Process: Fiscal Institutions and Individual Choice <oll2.libertyfund.org/titles/1073>

- Vol. 5. The Demand and Supply of Public Goods <oll2.libertyfund.org/titles/1067>

- Vol. 6 Cost and Choice: An Inquiry in Economic Theory <oll2.libertyfund.org/titles/1068>

- vol. 7 The Limits of Liberty: Between Anarchy and Leviathan) <oll2.libertyfund.org/titles/1827>

- vol. 8 Democracy in Deficit: The Political Legacy of Lord Keynes <oll2.libertyfund.org/titles/1097>

- Vol. 9 The Power to Tax: Analytical Foundations of a Fiscal Constitution <oll2.libertyfund.org/titles/2114>

- Vol. 10 The Reason of Rules: Constitutional Political Economy <oll2.libertyfund.org/titles/1826>

- Part 1 <oll2.libertyfund.org/titles/1030>

- Part 2 <oll2.libertyfund.org/titles/1031>

When Geoffrey Brennan begins his assessment of James M. Buchanan’s work with remarks on the author’s authority in interpreting his own creation, he addresses a general issue that is of particular significance when the author is, as in Buchanan’s case, a paradigm-creator whose life-work centers around, as Brennan puts it, “an identifiable research program.” For those who carry such a research program because they consider it more promising than relevant alternatives, there are essentially two alternatives attitudes towards the paradigm-creator’s work. They can look at it as a contribution to what K. R. Popper calls the world of “objective knowledge” and see their own task in further solidifying and expanding the theoretical edifice for which the paradigm-creator laid the foundations, but which he may not have already worked out fully and consistently in all its ramifications. Or, alternatively, they can treat it as a definitive and authoritative doctrine proclaimed by a “master” who has left for them little more than the exercise of interpreting his work most faithfully. The first attitude promotes science as a cumulative enterprise that is advanced by – again in Popper’s terminology – “conjectures and refutations” or “trial and error-elimination.” The second attitude easily leads to sectarianism, a fate that the paradigm Ludwig von Mises created appears to have suffered in some libertarian quarters.

When Geoffrey Brennan begins his assessment of James M. Buchanan’s work with remarks on the author’s authority in interpreting his own creation, he addresses a general issue that is of particular significance when the author is, as in Buchanan’s case, a paradigm-creator whose life-work centers around, as Brennan puts it, “an identifiable research program.” For those who carry such a research program because they consider it more promising than relevant alternatives, there are essentially two alternatives attitudes towards the paradigm-creator’s work. They can look at it as a contribution to what K. R. Popper calls the world of “objective knowledge” and see their own task in further solidifying and expanding the theoretical edifice for which the paradigm-creator laid the foundations, but which he may not have already worked out fully and consistently in all its ramifications. Or, alternatively, they can treat it as a definitive and authoritative doctrine proclaimed by a “master” who has left for them little more than the exercise of interpreting his work most faithfully. The first attitude promotes science as a cumulative enterprise that is advanced by – again in Popper’s terminology – “conjectures and refutations” or “trial and error-elimination.” The second attitude easily leads to sectarianism, a fate that the paradigm Ludwig von Mises created appears to have suffered in some libertarian quarters. It is hard to imagine a more fitting person to write a tribute to James Buchanan than his longtime associate and coauthor Geoffrey Brennan. Few understand Buchanan’s subtle positions with respect to philosophy, politics, and economics as well as Brennan. And Brennan’s tribute also captures the critical attitude that Buchanan believed we must always take. From his teacher Frank Knight, Buchanan learned many things, but perhaps the most important one was to treat all ideas critically and to hold nothing as sacrosanct. The onward-and-upward call that characterizes Buchanan’s intellectual career is what we must also adopt as our own if we want to make progress in the field of political economy.

It is hard to imagine a more fitting person to write a tribute to James Buchanan than his longtime associate and coauthor Geoffrey Brennan. Few understand Buchanan’s subtle positions with respect to philosophy, politics, and economics as well as Brennan. And Brennan’s tribute also captures the critical attitude that Buchanan believed we must always take. From his teacher Frank Knight, Buchanan learned many things, but perhaps the most important one was to treat all ideas critically and to hold nothing as sacrosanct. The onward-and-upward call that characterizes Buchanan’s intellectual career is what we must also adopt as our own if we want to make progress in the field of political economy. Geoffrey Brennan has given us a very comprehensive once-over-lightly treatment of the breadth of James Buchanan’s contributions. In reading it, I was struck again by that very breadth and how Buchanan was a major figure in several fundamental areas in economics. One of the great joys of reading his work is that, perhaps more than any other 20th century economist aside from F. A. Hayek, Buchanan asked questions that penetrated to the core of economics as a discipline. He was a master at stepping back from the conversation and asking us all to consider what it all meant and whether we were even talking about the right thing. His legacy, I believe, will be the ways in which he asked the kind of questions that undermined the conventional wisdom and led economists to look at their subject matter with new eyes. Once you see economics as about exchange and the institutions that frame it, as Buchanan does, you never see it the same way again.

Geoffrey Brennan has given us a very comprehensive once-over-lightly treatment of the breadth of James Buchanan’s contributions. In reading it, I was struck again by that very breadth and how Buchanan was a major figure in several fundamental areas in economics. One of the great joys of reading his work is that, perhaps more than any other 20th century economist aside from F. A. Hayek, Buchanan asked questions that penetrated to the core of economics as a discipline. He was a master at stepping back from the conversation and asking us all to consider what it all meant and whether we were even talking about the right thing. His legacy, I believe, will be the ways in which he asked the kind of questions that undermined the conventional wisdom and led economists to look at their subject matter with new eyes. Once you see economics as about exchange and the institutions that frame it, as Buchanan does, you never see it the same way again. As the leading figure in the Virginia School of Political Economy, James Buchanan traversed several disciplines. His greatest fame, as certified by the Nobel Prize committee, is as an economist, but Buchanan saw himself as operating in a tradition that reckons philosophers Thomas Hobbes and David Hume as exemplary members. It is, then, appropriate on this occasion to ask what his work means to political philosophy.

As the leading figure in the Virginia School of Political Economy, James Buchanan traversed several disciplines. His greatest fame, as certified by the Nobel Prize committee, is as an economist, but Buchanan saw himself as operating in a tradition that reckons philosophers Thomas Hobbes and David Hume as exemplary members. It is, then, appropriate on this occasion to ask what his work means to political philosophy. "The loss of faith in the socialist dream has not, and probably will not, restore faith in laissez-faire. But what are the effective alternatives? Does anarchism deserve a hearing, and, if so, what sort of anarchism?"

"The loss of faith in the socialist dream has not, and probably will not, restore faith in laissez-faire. But what are the effective alternatives? Does anarchism deserve a hearing, and, if so, what sort of anarchism?"