Last week we visited the Liberty Fund rare book room to take a look at a beautiful early edition of one of the most canonical, and canonizing, books in the English language, Johnson's Dictionary. This week, I thought it might be fun to look at a very different book, a 1906 copy of the key Taoist text, T'ai Shang Kan-Ying P'ien, owned by Liberty Fund's founder, Pierre Goodrich.

The Reading Room

Tai Shang Kan-Ying Pien: From the Liberty Fund Rare Book Room

Written by Lao Tzu (also spelled Lao Tse and Laozi) Tai Shang Kan-Ying Pien famously contains a statement of the moral rule best known in the West as "The Golden Rule" stated here as ""Regard your neighbor's gain as your own gain, and your neighbor's loss as your own loss." Goodrich's copy, which contains the full Chinese text, may seem an unusual book to find in the personal library of a mid-century midwestern businessman, but Goodrich was an unusual individual.All through the 1950s and into the 1960s, Goodrich was a trustee for an organization called the China Institute. The China Institute sought to increase academic and cultural exchange between the US and China and also worked to find appropriate employment for Chinese scholars and students stranded in the US because of political turmoil. The combination of educational and humanitarian goals must have suited Goodrich's personal priorities. Perhaps his interest in Tai Shang Kan-Ying Pien was spurred by his work with the China Institute. Perhaps his interest in China began with the book and with the many other Chinese texts in his collection.

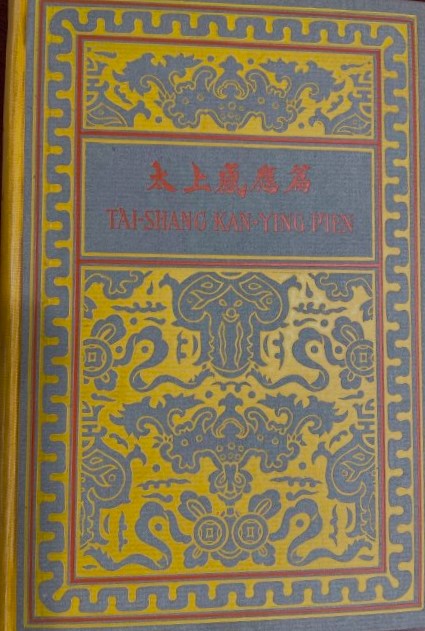

Whichever way the influence went, the book--in both paperback and the hardcover copy seen here--landed in Goodrich's library. And it is a charming edition. The cover is ornately decorated and sized appropriately for sliding into a pocket or bag.

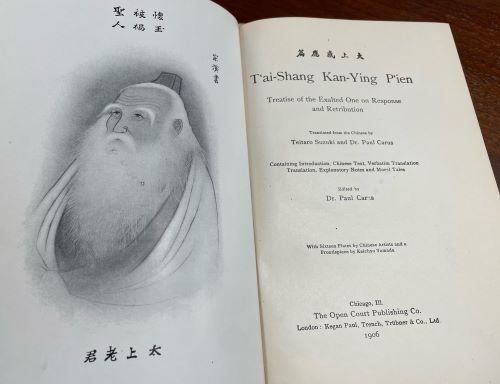

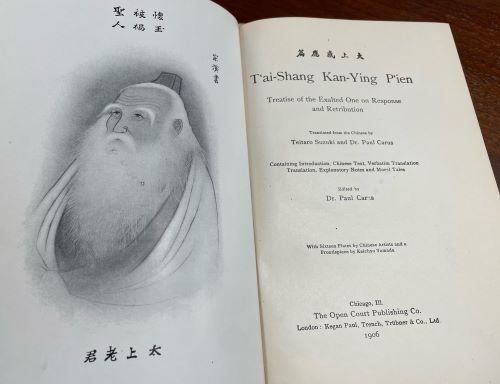

Inside the cover, the reader is presented with a frontispiece portrait of Lao Tzu, and a title page that lets us know that the book contains the full Chinese text, a translation, and a verbatim translation.

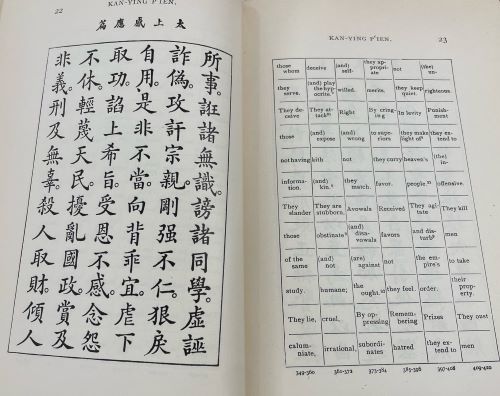

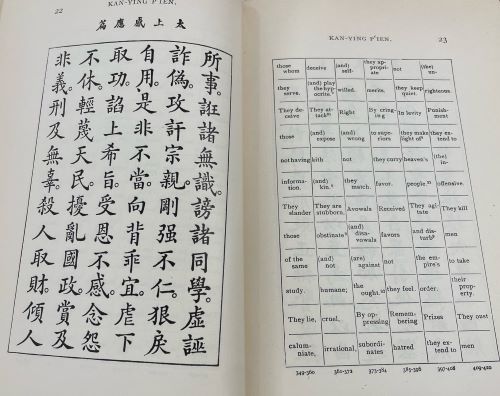

I was intrigued to see how the verbatim translation was done. The translator has put a box on the right hand page corresponding to each Chinese character on the left hand page. Inside the box goes the translation of the character. This allows those who don't read Chinese (like me!) to have a much better sense of how much meaning is conveyed by each individual character--much more than a single letter or syllable, or (often) even a single English word. It's an effective way to translate while still preserving the differences between the languages. And I think the verbatim translation can also serve as an invitation to create one's own interpretive translation, or at least to consider and assess the translator's choices.

As we continue visiting Liberty Fund's rare book room every Friday, we'll be looking at a lot more books from Goodrich's library and from the Liberty Fund collection. I hope they will convey, as these first two posts do, the wide-ranging interests of our founder, and the way we work to share them today.

Whichever way the influence went, the book--in both paperback and the hardcover copy seen here--landed in Goodrich's library. And it is a charming edition. The cover is ornately decorated and sized appropriately for sliding into a pocket or bag.

Inside the cover, the reader is presented with a frontispiece portrait of Lao Tzu, and a title page that lets us know that the book contains the full Chinese text, a translation, and a verbatim translation.

I was intrigued to see how the verbatim translation was done. The translator has put a box on the right hand page corresponding to each Chinese character on the left hand page. Inside the box goes the translation of the character. This allows those who don't read Chinese (like me!) to have a much better sense of how much meaning is conveyed by each individual character--much more than a single letter or syllable, or (often) even a single English word. It's an effective way to translate while still preserving the differences between the languages. And I think the verbatim translation can also serve as an invitation to create one's own interpretive translation, or at least to consider and assess the translator's choices.

As we continue visiting Liberty Fund's rare book room every Friday, we'll be looking at a lot more books from Goodrich's library and from the Liberty Fund collection. I hope they will convey, as these first two posts do, the wide-ranging interests of our founder, and the way we work to share them today.