The Works of Bastiat in Chronological Order 4: The Unfinished Treatises

Part 4: The Unfinished Treatises: The Social and Economic Harmonies and The History of Plunder (1850–51)

[Updated: 22 June, 2017 of a "work in progress"]

Note: for Parts 1-3 we have added final draft versions of material which will appear in the Collected Works, vol.3 "Economic Sophisms and WSWNS" and vol. 4 "Miscellaneous Writings on Economics." The material in this Part will come from CW5 (forthcoming).

|

|

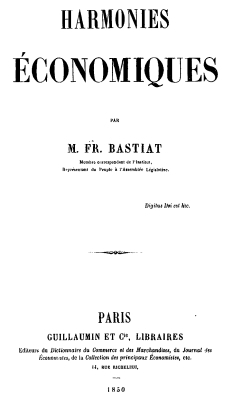

Title Page of the 1st ed. of Economic Harmonies (Jan., 1850) |

|

|

| Bastiat's tombstone in Rome | Title Page of the 2nd posthumous edition (July 1851) |

|

|

|

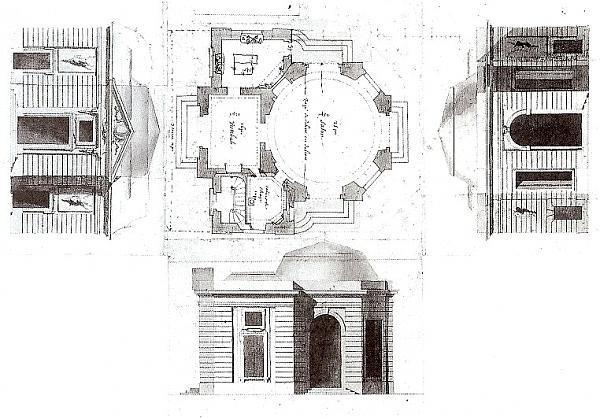

| Plan and pictures of the Butard hunting lodge where Bastiat wrote vol. 1 of Economic Harmonies over the summer of 1849 |

Introduction to the Collected Works in Chronological Order

Frédéric Bastiat’s 6 volume Collected Works published by Liberty Fund is a thematic collection.

- Vol. 1: The Man and the Statesman: The Correspondence and Articles on Politics, translated from the French by Jane and Michel Willems, with an introduction by Jacques de Guenin and Jean-Claude Paul-Dejean. Annotations and Glossaries by Jacques de Guenin, Jean-Claude Paul-Dejean, and David M. Hart. Translation editor Dennis O'Keeffe (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2011). /titles/2393.

- Vol. 2: The Law, The State, and Other Political Writings, 1843–1850, Jacques de Guenin, General Editor. Translated from the French by Jane Willems and Michel Willems, with an introduction by Pascal Salin. Annotations and Glossaries by Jacques de Guenin, Jean-Claude Paul-Dejean, and David M. Hart. Translation Editor Dennis O'Keeffe. Academic Editor, David M. Hart (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2012). /titles/2450.

- Vol. 3: Economic Sophisms and “What is Seen and What is Not Seen”. Jacques de Guenin, General Editor. Translated from the French by Jane and Michel Willems, with a foreword by Robert McTeer, and an introduction and appendices by the Academic Editor David M. Hart. Annotations and Glossaries by Jacques de Guenin, Jean-Claude Paul-Dejean, and David M. Hart. Translation Editor Dennis O'Keeffe. (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2017). (Not yet online)

- Vol. 4: Miscellaneous Works on Economics: From “Jacques-Bonhomme” to Le Journal des Économistes (forthcoming)

- Vol. 5: Economic Harmonies (forthcoming)

- Vol. 6: The Struggle Against Protectionism: The English and French Free-Trade Movements (forthcoming)

There will also be an online edition of Bastiat’s writings in chronological order. We have divided Bastiat’s works into 4 parts based upon the key periods and events in his life:

- Early Writings: The Bayonne and Mugron Years, 1819–1844

- The “Paris” Writings I: Bastiat and the Free Trade Movement (Oct. 1844 - Feb. 1848)

- The “Paris” Writings II: Bastiat the Politician, Anti-Socialist, and Economist (Feb. 1848 - Dec. 1850)

- The Unfinished Treatises: The Social and Economic Harmonies and The History of Plunder (1850–51)

For further information, see:

- the LF published edition of Bastiat’s Collected Works in 6 vols.

- the main Bastiat page in the OLL

- the Reader’s Guide to the Works of Frédéric Bastiat (1801–1850)

- the Liberty Matters discussion of Bastiat: Lead essay by Robert Leroux, "Bastiat and Political Economy" (July 1, 2013) with response essays by Donald J. Boudreaux, Michael C. Munger, and David M. Hart. </pages/bastiat-and-political-economy.

- Essays and other material about Bastiat

- Table of Contents of Bastiat’s Letters, Articles, and Books Listed in Chronological Order

The abbreviations used in this paper:

- 1847.02.14 = the work was published on Feb. 14, 1847

- ACLL = the English Anti-Corn Law League (1838-46)

- AEPS = L'Annuaire de l'économie politique et statistique (published by Guillaumin)

- ASEP = Annales de la Société d'Économie Politique. Publiées sous la direction de Alph. Courtois fils, secrétaire perpétuel, Tome premier 1846-1853 (Paris: Guillaumin,1889).

- CRANC = Compte rendu des séances de l'Assemblée Nationale Constituante

- CRANL = Compte rendu des séances de l'Assemblée Nationale Législative

- CF = Le Courrier française

- CH = Letters from Lettres d'un habitant des Landes, Frédéric Bastiat. Edited by Mme Cheuvreux. (1877)

- CW = the Collected Works of Frédéric Bastiat (Liberty Fund edition)

- CW1 = volume 1 of The Collected Works of Frédéric Bastiat

- OC = Oeuvres complètes de Frédéric Bastiat (Paillottet/Guillaumin edition)

- OC1.9 = the 9th article in vol. 1 of the Oeuvres complètes

- DEP = Dictionnaire d'économie politique

- DMH = text discovered by David M. Hart which is not in Paillottet's OC

- EH = Economic Harmonies

- EH1 = Economic Harmonies - the incomplete edtion publlished by FB during his lifetime in Jan. 1850 (11 chaps.)

- EH2 = Economic Harmonies - the expanded edtion with 22 chaps. publlished by Paillottet and Fontenay in July 1851

- Encyclopédie du dix-neuvième siècle (1846) = Encyclopédie du dix-neuvième siècle: répertoire universel des sciences, des lettres et des arts avec la biographie de tous les hommes célèbres, ed. Ange de Saint-Priest (Impr. Beaulé, Lacour, Renoud et Maulde, 1846)

- ES1 = Economic Sophisms. First Series (published Jan. 1846)

- ES1.10 = the tenth essay in ES1

- ES2 = Economic Sophisms. Second Series (published Jan. 1848)

- ES3 = Economic Sophisms. Third Series (compiled and published by LF in 2017 in CW3)

- FEE = Foundation for Economic Education

- JB = the journal Jacques Bonhomme (June 1848)

- JCPD = the original document was unpublished and is in the possession of Jean-Claude Paul-Dejean

- JDD = Journal des débats

- JDE = Journal des Économistes

- LÉ = Le Libre-Échange

- n.d. = no date of publication is known

- OC1 = Oeuvres complètes de Frédéric Bastiat, ed. Prosper Paillottet in 6 vols. (1854–55)

- OC2 = 2nd edition of Oeuvres complètes de Frédéric Bastiat, ed. Prosper Paillottet in 7 vols. (1862–64)

- PES = Political Economy Society (Société d'économie politique)

- PP = Prosper Paillottet, the editor of FB's OC

- RF = La République française Feb.-March 1848)

- Ronce = P. Ronce, Frédéric Bastiat. Sa vie, son oeuvre (Paris: Guillaumin, 1905).

- SP = La Sentinelle des Pyrénées

- PES = Political Economy Society (Société d'Économie Politique)

- T = either means "volume" (tome) or "Text" ID number (as in T.28)

- T.1 = text number one in the chronological table of contents of his writings

- WSWNS = What Is Seen and What Is Not Seen

The full method of citation for Bastiat’s writings (which is sometimes abbreviated in this article for reasons of space):

- T.102 (1847.01.17) "L'utopiste" (The Utopian) [Le Libre-Échange, 17 January 1847] [OC4.2.11, pp. 203–12] [ES2 11, CW3, pp. 187-98]

- text number in chronological ToC, date, French title, English title, place and date of original publication, location in French OC, location in ES, location in LF's CW volume.

- Letter 3. Bayonne, 18 March 1820. To Victor Calmètes [OC1, p. 3] [CW1, pp. 28-30]

- letter number in CW1, place and date letter written, recipient, location in OC, location in LF CW

Introduction to The Unfinished Treatises: The Social and Economic Harmonies and The History of Plunder (1850–51)↩

Youth of France! You will find the title of this book very ambitious. ECONOMIC HARMONIES! Have I aspired to reveal the plans of Providence in the social order and the workings of all the forces provided to the human race for the achievement of progress? Certainly not, but I would like to set you on the path to this truth: All legitimate interests are harmonious. This is the dominant idea in this book, and it is impossible not to recognize its importance.

(Dedication “To the Youth of France,” Economic Harmonies (1850).)

Key works:

- the “draft preface” (T.149) to his planned treatise from the fall of 1847, when he was giving lectures at the Taranne Hall in Paris CW1, pp. 316–20

- selected chapters from Economic Sophisms (CW3) and FEE ed.

- selected chapters from Economic Harmonies (CW5) and FEE ed.

- The proposed new chapters in the Note to Conclusion to the original Edition FEE ed.

- T.220 Property and Plunder (July 1848) CW2, pp. 147–84

Throughout this period (1848–50) the serious throat condition which would eventually kill Bastiat worsened[77] and he faced a race against time to finish his treatise on economics, the Economic Harmonies. He described the purpose of the Economic Harmonies as being the opposite to that of the Economic Sophisms - the latter was designed to “demolish” economic falsehood, while the former was designed to “build” economic truth.[78] He first began work on it in the fall of 1847 when he gave some lectures at the Taranne Hall in Paris when he also probably wrote a touching “draft preface” in the form of an ironic letter to himself.[79] In this letter he chastises himself for being too preoccupied with only one aspect of freedom, namely free trade or what he disparagingly called this “single crust of dry bread as food,” and having neglected the broader picture. To rectify this he wanted to apply the ideas of J.B. Say, Charles Comte, and Charles Dunoyer, to a study of “all forms of freedom” in a very ambitious research project in liberal social theory. In several letters[80] he refers to his project as a multi-volume study of “social harmonies” which would include a social, legal, and historical aspect, in addition to the economic. The plan was to devote one volume to the basic theory of social harmony before devoting another volume to the economic dimension, and then at least one volume to the “disturbing factors” which disrupted social harmony. The latter volume would be a study of the “disharmonies” which resulted from the upsetting of the natural harmony of voluntary and non-violent human interaction by “disturbing factors” (causes perturbatrices) such as war, slavery, and legal plunder. In other words, this volume would be “The History of Plunder” he had also planned to write.[81] Because he was so pressed for time he decided to focus on one aspect, the “economic harmonies”, and leave the others to another time.

It is possible to reconstruct the outlines of these proposed treatises from the scattered comments he made in letters, the Economic Sophisms, some essays (such as “Property and Plunder” (July 1848),[82] and unpublished drafts made available by Paillottet and Fontenay in the Oeuvres complètes.[83] Here is one format it might have taken:

- volume one on a general theory of how human society functions, to be called Social Harmonies with chapters on

- responsibility

- solidarity

- self interest or the “social motor or driving force”

- perfectibility

- public opinion

- the relationship between political economy and morality

- the relationship between political economy and politics

- the relationship between political economy and legislation

- the relationship between political economy and religion

- volume two on his economic theory, to be called Economic Harmonies with chapters on

- producers and consumers

- individualism and sociability

- the theory of Rent

- money

- credit

- wages

- savings

- population

- private services, public services

- taxation

- on machines

- free trade

- on middlemen

- raw materials and finished products

- on luxury

- volume three on disrupting factors or “disharmonies”, perhaps called The History and Theory of Plunder with chapters on

- plunder

- war

- slavery

- theocracy

- monopoly

- governmental exploitation

- false fraternity or communism

What follows is a reconstruction of Bastiat’s theory and history of plunder (using his own words) which comes from "The Physiology of Plunder" ES2 2:

There are only two ways of acquiring the things that are necessary for the preservation, enhancement, and improvement of life: PRODUCTION and Plunder.

Plunder is exercised on a vast scale in this world and is too universally woven into all the major events in the annals of humanity for any moral science, and above all Political Economy, to feel justified in disregarding it.

What separates the social order from perfection (at least from the degree of perfection it can attain) is the constant effort of its members to live and progress at the expense of one another.

When Plunder has become the means of existence of a large group of men (the class of plunderers) mutually linked by a social connection to others (the plundered), they soon contrive to pass a law that sanctions it (legal plunder) and a moral code that glorifies it.

[The stages of plunder in history]. First of all, there is WAR… SLAVERY… THEOCRACY… MONOPOLY.

The true and just law governing man is "The freely negotiated exchange of one service for another." Plunder consists in banishing by force or fraud the freedom to negotiate in order to receive a service without returning one in exchange. Plunder by force is exercised as follows: People wait for a man to produce something and then seize it from him with weapons. This is formally condemned by the Ten Commandments: Thou shalt not steal. When it takes place between individuals, it is called theft and leads to prison; when it takes place between nations, it is called conquest and leads to glory. When it takes place within a nation, between the government and its citizens, it is called legal plunder.

[In summary] Plunder consists in banishing by force or fraud the freedom to negotiate in order to receive a service without receiving another in return.

Having decided to focus his attention on finishing as much of the second volume on Economic Harmonies as he could, Bastiat returned to working on the project periodically as time permitted, publishing 4 draft chapters in the Journal des Économistes between September and December 1848 but seemed to drop the project soon after.[84]

He returned to it again during the summer of 1849 when the wealthy manufacturer and financial supporter of the economists, Casimir Cheuvreux, made a secluded hunting lodge on the outskirts of Paris available to Bastiat so he could work on his treatise in peace.[85] By the end of the year, Bastiat had enough material to publish the first part of Economic Harmonies (10 chapters) which appeared in January 1850.[86] He died on Christmas Eve, 1850 in Rome without having finished the second part of the treatise. Another 15 chapters were assembled from his papers by two of his friends, Paillottet and Fontenay, who published a second, larger edition of Economic Harmonies in June 1851.[87] A proposed list of chapters is all we have of what Bastiat intended to include in this magnum opus.

Some of his friends and colleagues didn’t know what to make of Bastiat’s treatise. They objected to his rejection of Malthusian pessimism concerning population growth - Bastiat believed Malthus had seriously underestimated the productive power of the free market once its shackles had been removed, and the ability and willingness of rational people to plan the size of their families. Others objected to his new theory of exchange as the mutually beneficial exchange of “services” which departed from the traditional view that “products were exchanged for products”, and his more general theory of rent (he saw it as just another service like any other) which denied the special nature of returns from land.[88] The American economist Henry Carey accused him of plagiarising his idea of “economic harmony”.[89] Still others could not see that behind his witty journalism, like the story of “The Broken Window” or “One Profit versus Two Losses” (May 1847),[90] or his playful but clever use of Robinson Crusoe and Friday thought experiments in Economic Harmonies, lay some profound and original insights about opportunity costs (a concept Bastiat probably invented), the multiplier effect and the mathematical calculation of economic losses, and the nature of human economic action, respectively. Even his friend and colleague, Gustave de Molinari, regarded his contribution to economics as being more like that of the popularizer Benjamin Franklin, than a true original thinker like J.B. Say.[91]

Modern economists are divided over the originality of Bastiat’s Economic Harmonies, with opinion ranging from the harshly dismissive - Schumpeter said he was no theorist at all[92] - to modern Austrian economists who see him as an Austrian economist ahead of his time,[93] and Public Choice economists who believe Bastiat had a sophisticated understanding of the economics of political decision-making.[94]

Some of Bastiat’s interesting and innovative ideas in Economic Harmonies include the following:

- an individualist methodology of the social sciences with his use of “Crusoe economics” to analyse the science of human action in the abstract,[95] and the idea that human beings make economic decisions even before they become involved in exchanging goods and services with others

- the idea that individuals are thinking, evaluating, choosing, and thus “acting” beings in the Austrian sense of the word[96]

- an early form of subjective value theory with his insight that individuals “compare, assess, and evaluate” goods and services before they engage in trade

- labour which produces physical (material) goods as well as “immaterial goods” (or services) is productive and these goods and services have value

- all human transactions are the reciprocal or mutual exchange of services (or “service for service”)[97]

- Ricardian rent theory is wrong because there is nothing special about the productivity of land, and thus charging rent for the use of the land is productive and just, and hence a “service” like any other

- the idea that in the absence of government coercion the free market produces a "harmonious order", and the opposite idea that when coercion or violence intrudes (what Bastiat called “disturbing factors” such as war, enslavement, plunder, government regulations, tariffs and monopolies) there is “disharmony”, injustice, and economic misery [98]

- a consumer-centric view of economic activity, that consumption is the goal and thus determines the economic activity of producers and entrepreneurs, or in other words, that the “wants” of people are the goal of economic activity, giving rise to “efforts” by producers and entrepreneurs to satisfy those wants, and eventually yielding “satisfactions” for consumers

- that human wants are unlimited and that the means to satisfy those needs will increasingly become available in a free economy

- that Malthusian pessimism about population growth is wrong because he underestimated the productivity of the free market once its shackles had been removed, and the ability and willingness of rational people to plan the size of their families. He also thought larger and more concentrated populations expanded the size of the market, increased the division of labour, and reduced costs for trading with others, all of which increased wealth.

- the interdependence or interconnectedness of all economic activity, with his version of Leonard Read’s “I, Pencil” story: the village cabinet maker and the student

To these should be added other economic ideas which he discussed at greater length elsewhere in his writings:

- the transmission of economic information through the economy which he likened to flows of water or electricity

- the idea of opportunity cost - the “seen” and the “unseen”

- his early use of the term ceteris paribus, which was contemporaneous with but independent of John Stuart Mill’s use[99]

- the free market "harmoniously" solves the problem of economic coordination, as in the provisioning of Paris[100]

- the idea of the ricochet effect, or the multiplier which can be both negative (tariffs) and positive (steam power) in its impact on the economy[101]

- the quantification of the impact of economic events ("double incidence of loss")

- the connection between free trade and peace

- his "Public Choice" like theory of politics (politicians and bureaucrats have interests, rent seeking)

- his theory of the "economic sociology" of the State (disturbing factors, plunder, war, legal plunder, Malthusian limits to the size of the state)

- the idea of negative factor productivity in “The Negative Railway” (c. 1845)

- his idea that political economy was also a “moral economy” since it assumed or was based upon idea of private property rights and voluntary exchange of that property

- his awareness of the danger of paper money in the hands of a state which wants to expand its activity without imposing the taxes necessary to pay for them

The circuitous and difficult progression of his unfinished treatises can be seen in the following:

- the “draft preface” to his planned treatise from the fall of 1847, when he was giving lectures at the School of Law

- his draft chapters published as articles in the JDE (late 1848)

- Economic Harmonies (1st ed. 1850). (1st 10 chapters).

- Economic Harmonies (2nd enlarged ed. 1851). (orignal 10 chapters plus 15 reconstructed from his papers).

- his sketches of the theory and history of plunder in he "Conclusion" to ES1 (dated November 1845) and the first 2 chapters of ES2, “The Physiology of Plunder” and “Two Moralities” (probably written in late 1847)

- several articles in JDE, “Theft by Subsidy” (Jan. 1846), “Property and Law” (May 1848), “Plunder and Law” (May 1850)

- the pamphlet The Law (June 1850)

Faced with the double blow of being shunned by his colleagues in the Political Economy Society and knowing that he would not live to finish his book, Bastiat wrote in July 1850 to one of his friends, Roger Fontenay, who would compile the second, enlarged edition of Economic Harmonies after his death. It is a suitable epitaph for his life:

EndnotesPerhaps you are too ardently in favor of the Harmonies in the face of opposition from Le Journal des économistes. Middle-aged men do not easily abandon well-entrenched and long-held ideas. For this reason, it is not to them but to the younger generation that I have addressed and submitted my book. People will end up acknowledging that value can never lie in materials and the forces of nature. From this can be drawn the absolutely free characteristic of gifts from God in all their forms and in all human transactions.

This leads to the mutual nature of services and the absence of any reason for men to be jealous of and hate each other. This theory should bring all the schools together on a common ground. Since I live with this conviction, I am waiting patiently, since the older I become the clearer I perceive the slowness of human evolution.

However, I do not conceal a personal wish. Yes, I would like this theory to attract enough followers in my lifetime (even if only two or three) for me to be assured before dying that it will not be abandoned if it is true. Let my book generate just one other and I will be satisfied. This is why I cannot encourage you too strongly to concentrate your thinking on capital, which is a huge subject and may well be the cornerstone of political economy. I have no more than touched upon it; you will go further than I and will correct me if need be. Do not fear that I will take offence. The economic horizons are unlimited: to see new ones makes me happy, whether it was I that discovered them or someone else that is showing them to me.[102]

-

Most historians have thought Bastiat died of tuberculosis (which killed his parents when he was a young boy) but in some of his letters he talk about a lump in his throat, which suggests something more like throat cancer. See, Letter 184 to M. Cheuvreux, Mugron 14 July 1850, CW1, p.260–62: "For some time now, I have had a very local pain in the larynx that is unbearable because it is continuous."; Letter 191 to Louise Cheuvreux, Lyons 14 Sept. 1850, CW1, pp. 270–73: "Oh, how fragile is the human frame! Here I am, the plaything of a tiny pimple (lump) growing in my larynx."; and Letter 203 to Félix Coudroy, Rome 11 Nov. 1850, CW1, pp. 288–89: "I would ask for one thing only, and that is to be relieved of this piercing pain in the larynx; this constant suffering distresses me. Meals are genuine torture for me. Speaking, drinking, eating, swallowing saliva, and coughing are all painful operations." In the Foreword to the second enlarged edition of Economic Harmonies (July 1851) Prosper Paillottet and Roger de Fontenay state that by the end of the summer of 1850 Bastiat had completely lost the use of his voice. See, "The Cause of Bastiat's Untimely Death," in Bastiat's Political Writings: Anecdotes and Reflections, in CW1, pp. 413–14. ↩

-

See Letter 65 to Mr. Richard Cobden, Mugron, 25 June 1846, CW1, pp. 105–6. ↩

-

T.149 “A Draft Preface to the Economic Harmonies” (Fall 1847), CW1, pp. 316–20. ↩

-

In a letter to Richard Cobden (Aug. 1848) he explained that his aim was “to set out the true principles of political economy as I see them, and then to show their links with all the other moral sciences”, Letter 107 to Richard Cobden, Paris, 18 August 1848, CW, pp. 160–61. In a letter to Casimir Cheuvreux (July 1850) he stated that “When I said that the laws of political economy are harmonious, I did not mean only that they harmonize with each other, but also with the laws of politics, the moral laws, and even those of religion”, Letter 184 to M. Cheuvreux, Mugron, 14 July 1850, CW1, p.260–62. See also, his Letter 39 to Félix Coudroy, Paris, 6 June 1845, CW1, pp. 62–65; and Letter 108 to Félix Coudroy, Paris, 26 August 1848, CW1, pp. 161–63. Prosper Paillottet and Roger de Fontenay’s “Foreword” to the second enlarged edition of Economic Harmonies (July 1851) quote an unpublished piece by Bastiat on this plan. ↩

-

In a note at the end of the “Conclusion” to ES1 Paillottet tells us that “The influence of plunder on the destiny of the human race preoccupied him greatly. After having covered this subject several times in the Sophisms and the Pamphlets (see in particular T.220 ”Property and Plunder“ (July 1848), CW2, pp. 147–184, and T.257 ”Plunder and Law“ (May 1850), CW2, pp. 266–76), he planned a more ample place for it in the second part of the Harmonies, among the disturbing factors. Lastly, as the final evidence of the interest he took in it, he said on the eve of his death: "A very important task to be done for political economy is to write the history of plunder. It is a long history in which, from the outset, there appeared conquests, the migrations of peoples, invasions, and all the disastrous excesses of force in conflict with justice. Living traces of all this still remain today and cause great difficulty for the solution of the questions raised in our century. We will not reach this solution as long as we have not clearly noted in what and how injustice, when making a place for itself amongst us, has gained a foothold in our customs and our laws.”“ In ES1 ”Conclusion", in CW3, p. 110. FEE ed. ↩

-

T.220 "Propriété et spoliation" (Property and Plunder). Originally published in Le Journal des débats, 24 July 1848, CW2, pp. 147–84. ↩

-

See in particular the list of planned chapters following chapter 10 Competition" in the published version of Economic Harmonies (1851). FEE ed. ↩

-

Bastiat, T.223 "Harmonie économiques. I, II, III (Des besoins de l'homme)", Journal des Économistes, T. XXI, No. 87, 15 Sept. 1848, pp. 105–20; T.225 "Harmonie économiques. IV", Journal des Économistes, T. XXII, No. 93, 15 Dec. 1848, pp. 7–18. Our edition of Economic Harmonies will be in CW5 (forthcoming). FEE ed. ↩

-

See Bastiat’s description in Letter 140 to Bernard Domenger, Paris, Tuesday, 13 … (Summer 1849), in CW1, pp. 205–6. ↩

-

The first part of Economic Harmonies published in Bastiat’s lifetime contained only the first 10 chapters and appeared in Jan. 1850 but was not reviewed by the JDE until June. See, "Harmonies économies, par M. Frédéric Bastiat. (Compte rendu par. M. A. Clément), JDE, T. 26, no. 111, 15 juin 1850, pp. 235–47. Bastiat realised that he had upset the economists with his radically new interpretations of key aspects of orthodox classical economics such as rent, Malthusian population theory, and value theory. Bastiat mentions its appearance in January 1850 in Letter 158 to Félix Coudroy, Paris, Ja. 1850, CW1, pp. 228–9. ↩

-

The second, enlarged edition of the Economic Harmonies was published posthumously by “les Amis de Bastiat” (the friends of Bastiat), or Prosper Paillottet and Roger de Fontenay, who added an additional 15 chapters which they had reconstructed from Bastiat’s notes and drafts. See, Harmonies économiques. 2me Édition augmentées des manuscrits laissés par l'auteur. Publiée par la Société des amis de Bastiat (Paris: Guillaumin, 1851). Introduction by Prosper Paillottet and Roger de Fontenay. It was reviewed by Joseph Garnier in JDE in August 1851 so it may have been published in June or July. See, Garnier, Joseph Garnier, "La deuxième édition des Harmonies économiques de Frédéric Bastiat," JDE, T. 29, no. 124, 15 août 1851, pp. 312–16. ↩

-

The Political Economy Society discussed his chapter on rent in Economic Harmonies at their Dec. 10, 1849 meeting. In a very vigorous and critical discussion they rejected his theory. See, Annales de la Société d’Économie politique. Publiés sous la direction de Alph. Courtois fils, secrétaire perpétuel. Tome premier, 1846–1853 (Paris: Guillaumin, 1889), p. 94. Also T.245 [1849.12.10] “Comments at a Meeting of the Political Economy Society on State Support for popularising Political Economy, his idea of Land Rent in Economic Harmonies, the Tax on Alcohol, and Socialism” (10 Dec. 1849), in CW4 (forthcoming). ↩

-

See the debate in the JDE in the first half of 1851: “Les Harmonies économiques. Lettre de M. Carey; Réponse de MM. Frédéric Bastiat et A. Clément,” JDE, T. 28, N° 117, 15 janvier 1851, pp. 38–54; “Observations de M. H.C. Carey sur la dernière note de FRÉDÉRIC BASTIAT,” JDE, T. 29, N° 121, 15 mai 1851, pp. 43–54; “Correspondance. Au sujet des reclamations de M. H. Carey, par M. PAILLOTTET,” JDE, T. 29, N° 122, 15 juin 1851, pp. 156–60. The end result was that it seems they had both independently come upon the same idea at the same time. ↩

-

T.128 ES3 4 "Un profit contre deux pertes" (One Profit versus Two Losses), Le Libre-Échange, 9 May 1847, no. 24, p. 192 in CW3, pp. 271–76. ↩

-

Molinari, "Nécrologie. — Frédéric Bastiat, notice sur sa vie et ses écrits," JDE, T. 28, N° 118, 15 février 1851, pp. 180–96. ↩

-

“I do not hold that Bastiat was a bad theorist. I hold that he was no theorist.” Joseph A. Schumpeter, History of Economic Analysis. Edited from Manuscript by Elizabeth Boody Schumpeter (New York: Oxford University Press, 1974). 1st ed. 1954), p. 500–1. ↩

-

James A. Dorn, “Bastiat: A Pioneer in Constitutional Political Economy” Journal des Economistes et des Etudes Humaines, vol. 11, no. 2/3 (June 2001); Caplan, Bryan; Stringham, Edward (2005). “Mises, Bastiat, Public Opinion, and Public Choice”. Review of Political Economy 17: 79–105. https://econfaculty.gmu.edu/bcaplan/pdfs/misesbastiat.pdf; Michael C. Munger, “Did Bastiat Anticipate Public Choice?” in Liberty Matters: Robert Leroux, "Bastiat and Political Economy" (July 1, 2013) /pages/bastiat-and-political-economy#conversation3. See also the Liberty Matters discussion of Bastiat: Lead essay by Robert Leroux, "Bastiat and Political Economy" (July 1, 2013) with response essays by Donald J. Boudreaux, Michael C. Munger, and David M. Hart. /pages/bastiat-and-political-economy. ↩

-

See for example essays by Murray N. Rothbard, Thomas DiLorenzo, Jörg Guido Hülsmann: Rothbard, Classical Economics: An Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought. Volume II (Auburn, Alabama: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2006), Especially chap. 14 “After Mill: Bastiat and the French laissez-faire tradition,” pp. 439–75. Thomas J. DiLorenzo, “Frédéric Bastiat: Between the French and Marginalist Revolutions,” in 15 Great Austrian Economists. Edited and with and Introduction by Randall G. Holcombe (Auburn Alabama: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 1999), pp. 59–69. Jörg Guido Hülsmann, “Bastiat’s Legacy in Economics,” The Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics, vol. 4, no. 4, (Winter 2001), pp. 55–70. ↩

-

See, "Bastiat’s Invention of 'Crusoe Economics'," in the Introduction to CW3, pp. lxiv-lxvii. ↩

-

See, "Human Action" in Further Aspects of Bastiat's Thought, in CW4 (forthcoming). ↩

-

See, "Service for Service" in Further Aspects of Bastiat's Thought, in CW4 (forthcoming). ↩

-

See, "Harmony and Disharmony" and "Disturbing and Restorative Factors" in Further Aspects of Bastiat's Thought, in CW4 (forthcoming). ↩

-

See, "Ceteris Paribus" in Further Aspects of Bastiat's Thought, in CW4 (forthcoming). ↩

-

See, "Society is One Great Market" in Further Aspects of Bastiat's Thought, in CW4 (forthcoming). ↩

-

See, "The Sophism Bastiat never wrote: The Sophism of the Ricochet Effect" in Further Aspects of Bastiat's Thought, in CW3, pp. 457–61. ↩

-

Letter 180 to M. de Fontenay, Les Eaux-Bonnes, 3 July 1850, CW1, pp. 255–56. ↩