The Works of Bastiat in Chronological Order 1: the Early Writings 1819-1844

Part 1. Early Writings: The Bayonne and Mugron Years, 1819–1844

[Updated: 22 June, 2017 of a "work in progress"]

Note: We have added final drfat versions of material which will appear in the Collected Works, vol.3 "Economic Sophisms and WSWNS"; and Collected Works, vol. 4 "Miscellaneous Writings on Economics."

Material added from CW4 is in BOLD.

|

|

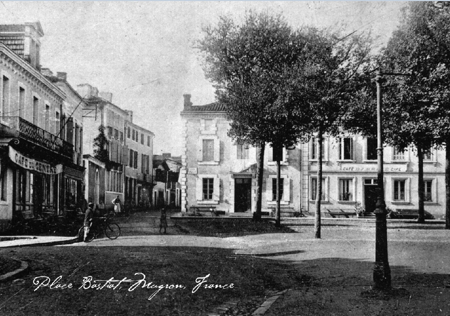

Place Bastiat, Mugron |

|

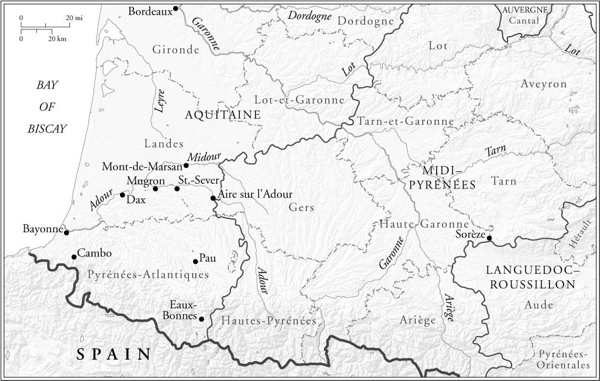

Les Landes and its main towns |

Introduction to the Collected Works in Chronological Order

The printed version of Frédéric Bastiat’s 6 volume Collected Works published by Liberty Fund is a thematic collection.

- Vol. 1: The Man and the Statesman: The Correspondence and Articles on Politics, translated from the French by Jane and Michel Willems, with an introduction by Jacques de Guenin and Jean-Claude Paul-Dejean. Annotations and Glossaries by Jacques de Guenin, Jean-Claude Paul-Dejean, and David M. Hart. Translation editor Dennis O’Keeffe (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2011). /titles/2393.

- Vol. 2: The Law, The State, and Other Political Writings, 1843–1850, Jacques de Guenin, General Editor. Translated from the French by Jane Willems and Michel Willems, with an introduction by Pascal Salin. Annotations and Glossaries by Jacques de Guenin, Jean-Claude Paul-Dejean, and David M. Hart. Translation Editor Dennis O’Keeffe. Academic Editor, David M. Hart (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2012). /titles/2450.

- Vol. 3: Economic Sophisms and “What is Seen and What is Not Seen”. Jacques de Guenin, General Editor. Translated from the French by Jane and Michel Willems, with a foreword by Robert McTeer, and an introduction and appendices by the Academic Editor David M. Hart. Annotations and Glossaries by Jacques de Guenin, Jean-Claude Paul-Dejean, and David M. Hart. Translation Editor Dennis O'Keeffe. (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2017). (Not yet online.)

- Vol. 4: Miscellaneous Works on Economics (forthcoming)

- Vol. 5: Economic Harmonies (forthcoming)

- Vol. 6: The Struggle Against Protectionism: The English and French Free-Trade Movements (forthcoming)

We are also creating a chronological version of Bastiat’s writings which only be available online. As the printed version becomes available in digital form we will add it to the chronological version. Thus, this is a work in progress. There is a complete list of all of Bastiat’s writings in order of appearance here. We have divided Bastiat’s works into 4 parts based upon the key periods and events in his life:

- Early Writings: The Bayonne and Mugron Years, 1819–1844

- The “Paris” Writings I: Bastiat and the Free Trade Movement (Oct. 1844 - Feb. 1848)

- The “Paris” Writings II: Bastiat the Politician, Anti-Socialist, and Economist (Feb. 1848 - Dec. 1850)

- The Unfinished Treatises: The Social and Economic Harmonies and The History of Plunder (1850–51)

For further information, see:

- the LF published edition of Bastiat’s Collected Works in 6 vols.

- the main Bastiat page in the OLL

- the full list of Bastiat’s Letters, Articles, and Books Listed in Chronological Order which also includes a detailed discussion of the sources used in compiling this collection

- the Reader’s Guide to the Works of Frédéric Bastiat (1801–1850)

- the Liberty Matters discussion of Bastiat: Lead essay by Robert Leroux, “Bastiat and Political Economy” (July 1, 2013) with response essays by Donald J. Boudreaux, Michael C. Munger, and David M. Hart. </pages/bastiat-and-political-economy.

- Essays and other material about Bastiat

The abbreviations used in this collection:

- 1847.02.14 = the work was published on Feb. 14, 1847

- ACLL = the English Anti-Corn Law League (1838-46)

- AEPS = L'Annuaire de l'économie politique et statistique (published by Guillaumin)

- ASEP = Annales de la Société d'Économie Politique. Publiées sous la direction de Alph. Courtois fils, secrétaire perpétuel, Tome premier 1846-1853 (Paris: Guillaumin,1889).

- CRANC = Compte rendu des séances de l'Assemblée Nationale Constituante

- CRANL = Compte rendu des séances de l'Assemblée Nationale Législative

- CF = Le Courrier française

- CH = Letters from Lettres d'un habitant des Landes, Frédéric Bastiat. Edited by Mme Cheuvreux. (1877)

- CW = the Collected Works of Frédéric Bastiat (Liberty Fund edition)

- CW1 = volume 1 of The Collected Works of Frédéric Bastiat

- OC = Oeuvres complètes de Frédéric Bastiat (Paillottet/Guillaumin edition)

- OC1.9 = the 9th article in vol. 1 of the Oeuvres complètes

- DEP = Dictionnaire d'économie politique

- DMH = text discovered by David M. Hart which is not in Paillottet's OC

- EH = Economic Harmonies

- EH1 = Economic Harmonies - the incomplete edtion publlished by FB during his lifetime in Jan. 1850 (11 chaps.)

- EH2 = Economic Harmonies - the expanded edtion with 22 chaps. publlished by Paillottet and Fontenay in July 1851

- Encyclopédie du dix-neuvième siècle (1846) = Encyclopédie du dix-neuvième siècle: répertoire universel des sciences, des lettres et des arts avec la biographie de tous les hommes célèbres, ed. Ange de Saint-Priest (Impr. Beaulé, Lacour, Renoud et Maulde, 1846)

- ES1 = Economic Sophisms. First Series (published Jan. 1846)

- ES1.10 = the tenth essay in ES1

- ES2 = Economic Sophisms. Second Series (published Jan. 1848)

- ES3 = Economic Sophisms. Third Series (compiled and published by LF in 2017 in CW3)

- FEE = Foundation for Economic Education

- JB = the journal Jacques Bonhomme (June 1848)

- JCPD = the original document was unpublished and is in the possession of Jean-Claude Paul-Dejean

- JDD = Journal des débats

- JDE = Journal des Économistes

- LÉ = Le Libre-Échange

- n.d. = no date of publication is known

- OC1 = Oeuvres complètes de Frédéric Bastiat, ed. Prosper Paillottet in 6 vols. (1854–55)

- OC2 = 2nd edition of Oeuvres complètes de Frédéric Bastiat, ed. Prosper Paillottet in 7 vols. (1862–64)

- PES = Political Economy Society (Société d'économie politique)

- PP = Prosper Paillottet, the editor of FB's OC

- RF = La République française Feb.-March 1848)

- Ronce = P. Ronce, Frédéric Bastiat. Sa vie, son oeuvre (Paris: Guillaumin, 1905).

- SP = La Sentinelle des Pyrénées

- PES = Political Economy Society (Société d'Économie Politique)

- T = either means "volume" (tome) or "Text" ID number (as in T.28)

- T.1 = text number one in the chronological table of contents of his writings

- WSWNS = What Is Seen and What Is Not Seen

The full method of citation for Bastiat’s writings (which is sometimes abbreviated in this article for reasons of space):

- T.102 (1847.01.17) "L'utopiste" (The Utopian) [Le Libre-Échange, 17 January 1847] [OC4.2.11, pp. 203–12] [ES2 11, CW3, pp. 187-98]

- text number in chronological ToC, date, French title, English title, place and date of original publication, location in French OC, location in ES, location in LF's CW volume.

- Letter 3. Bayonne, 18 March 1820. To Victor Calmètes [OC1, p. 3] [CW1, pp. 28-30]

- letter number in CW1, place and date letter written, recipient, location in OC, location in LF CW

Table of Contents

- Letter 1. Bayonne, 12 Sept. 1819. To Victor Calmètes

- Letter 2. Bayonne, 5 March 1820. To Victor Calmètes

- Letter 3. Bayonne, 18 March 1820. To Victor Calmètes

- Letter 4. Bayonne, 10 Sept. 1820. To Victor Calmètes

- Letter 5. Bayonne, Oct. 1820. To Victor Calmètes

- Letter 6. Bayonne, 29 Apr. 1821. To Victor Calmètes

- Letter 7. Bayonne, 10 Sept. 1821. To Victor Calmètes

- Letter 8. Bayonne, 8 Dec. 1821. To Victor Calmètes

- Letter 9. Bayonne, 20 Oct. 1822. To Victor Calmètes

- Letter 10. Bayonne, Dec. 1822. To Victor Calmètes

- Letter 11. Bayonne, 15 Dec. 1824. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 12. Bayonne, 8 Jan. 1825. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 13. Bordeaux, 9 Apr. 1827. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 14. Mugron, 3 Dec. 1827. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 15. Mugron, 12 March 1829. To Victor Calmètes

- Letter 16. Mugron, Jul. 1829. To Victor Calmètes

- Letter 17. Bayonne, 4 Aug. 1830. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 18. Bayonne, 5 Aug. 1830. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 19. Bayonne, 22 Apr. 1831. To Victor Calmètes

- Letter 20. Bordeaux, 2 March 1834. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 21. Bayonne, 16 June 1840. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 22. Madrid, 6 Jul. 1840. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 23. Madrid, 16 Jul. 1840. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 24. Madrid, 17 Aug. 1840. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 25. Lisbonne, 24 Oct. 1840. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 26. Lisbonne, 7 Nov. 1840. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 27. Paris, 2 Jan. 1841. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 28. Paris, 11 Jan. 1841. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 29. Bagnères, 10 Jul. 1844. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 30. Eaux-Bonnes, 26 Jul. 1844. To Félix Coudroy

- Letter 209 to M. Muiron (Eaux-Bonnes, 7 Nov. 1844) [CW4 draft]

- Letter 31. Mugron, 9 Nov. 1844. To M. Laurence

- Endnotes for the Correspondence

- T.1 (1822.01.12) "Letter to a Candidate"

- T.296 [1820s.??] "On the Romans as Plundering Villains" (before 1830) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.297 [1820s.??] "On the Romans and Self-sacrifice" (before 1830) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.289 [1830.??] "The Poetry of Civilization" (c. 1830) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T2 (1830.11) "To the Electors of the Département of the Landes"

- T.104 [1831.??] "Letter to M. Saulnier on the cost of government in the U.S. and France" (c. 1831) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.318 [1832.??] "Election Manifesto" (c. 1832) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.285 [1833.??] "On Certainty" (c. 1833) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.3 (1834.??) "On a New Secondary School to Be Founded in Bayonne"

- T.4 [1834.??] "On a Petition in Support of Polish Refugees" (c. 1834) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.5 (1834.04) "Reflections on the Petitions from Bordeaux, Le Havre, and Lyons Relating to the Customs Service"

- T.6 [1837.09.01] "A Letter to "Charles" in Support of a Polish Refugee" (Mugron, 1 Sept. 1835) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.7 [1837.06.16] Five Articles on "The Canal beside the Adour" (18 June 1837, La Chalosse) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.8 (1837.06.??) "Untitled Fragment" (On Canal shares)

- T.9 (1838.02.11) "Reflections on the Question of Dueling (Report)" (La Chalosse, Feb. 1838)

- T.10 (1838.04.01) "Two Articles on the Basque Language" (La Chalosse, Apr. 1838)

- T.11 (1840.??) "Parliamentary Reform"

- T.12 (1841.01) "The Tax Authorities and Wine"

- T.286 [1841.01.15] "Proposals for an Association of Wine Producers" (15 Jan. 1841) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.298 [1843.??] "On the Cost of Being Governed" (1843) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.13 (1843.01.22) "Memoir Presented to the Société d’agriculture, commerce, arts, et sciences du département des Landes on the Wine-Growing Question"

- T.14 (1843.03.21) "Parliamentary Conflicts of Interest" (SP, March 1843)

- T.266 (1843.05.18) "Free Trade. State of the Question in England. 1st Article" (SP, 18 May, 1843) [CW6 not yet available]

- T.267 (1843.05.25) "Free Trade. State of the Question in England. 2nd Article" (SP, 25 May 1843) [CW6 not yet available]

- T.268 (1843.06.01) "Free Trade. State of the Question in England. 3rd Article" (SP, 1 June 1843) [CW6 not yet available]

- T.269 (1843.12.02) "The Balance of Trade" (SP, 2 Dec. 1843) [CW6 not yet available]

- T.270 (1843.12.13) "To the Editor in Chief of La Presse on Navigation" (SP, 13 Dec. 1843) [CW6 not yet available]

- T.271 (1843.12.14) "Reply to La Presse" (SP, 14 Dec. 1843) [CW6 not yet available]

- T.15 (1844.??) "Freedom of Trade"

- T.16 (1844.??) "Proposition for the Creation of a School for Sons of Sharecroppers"

- T.17 [1844.07] "On the Allocation of the Land Tax in the Department of Les Landes" (July 1844) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.272 (1844.07.02) "The Sugar Question in England in England" SP, 2 July 1844) [CW6 not yet available]

- T.18 [1844.08.03] "Two Articles on Postal Reform I" (3-6 Aug. 1844, SP) [CW4 draft 16 June 2017]

- T.19 (1844.10.15) "On the Influence of French and English Tariffs on the Future of the Two People" (JDE, 10 Oct. 1844) [CW6 not yet available]

Introduction to Part 1: Early Writings: The Bayonne and Mugron Years, 1819–1844↩

[Updated: 21 June, 2017]

If this vast machine always kept itself within the limits of its responsibilities, elected representatives would be superfluous. However, the government is a living body at the center of the nation, which, like all organized entities, tends strongly to preserve its existence, to increase its well-being and power, and to expand indefinitely its sphere of action. Left to itself, it soon exceeds the limits which circumscribe its mission. It increases beyond all reason the number and wealth of its agents. It no longer administers, it exploits. It no longer judges, it persecutes or takes revenge. It no longer protects, it oppresses.

This would be the way all governments operate, the inevitable result of this law of movement with which nature has endowed all organized beings, if the people did not place obstacles in the way of governmental encroachments.

(“To the Electors of the Department of Les Landes” (November, 1830), CW1, p. 344.)

Key works from this period:

- T.2 “To the Electors of the Department of Les Landes” (November, 1830), CW1, pp. 341–52 and in Early Writings.

- T.5 “Reflections on the Petitions from Bordeaux, Le Havre, and Lyons Relating to the Customs Service” (April 1834) CW2, pp. 1–9 and Early Writings

- T.7 "The Canal beside the Adour" (June, 1837) Early Writings

- T.12 "The Tax Authorities and Wine" (January, 1841) CW2, pp. 10–23 and Early Writings

- T.266 “Free Trade. State of the Question in England” (SP, May, 1843) (CW6 forthcoming)

- T.18 "Postal Reform" (August, 1844) Early Writings

- T.17 “On the Allocation of the Land Tax in the Department of Les Landes” (July, 1844) Early Writings

- T.19 “On the Influence of French and English Tariffs on the Future of the Two People” (JDE, 10 Oct. 1844) (CW6 forthcoming)

The Early Writings were written in his home Département of Les Landes (1841 population 288,000), in particular the regional capital city of Bordeaux (it was the capital of the region of Aquitaine and had a population in 1841 of 99,000), the regional port city of Bayonne (1841 population 17,000), and the small farming town of Mugron (1841 population 2,190) where he lived for the first 44 years of his life. They are concerned with local matters but they show his growing interest in economics which he studied in a private in considerable depth.

He became a landowner in Aug. 1825 at the age of 24 when his grandfather died (his parents had died when he was young and he was raised by his aunt and grandfather) and left him 250 hectares (620 acres) of land in Mugron which included several sharecroppers.[1] They produced wine, cattle, and some general crops on reasonably good soil on the banks of the Adour river. Other agricultural activities included raising sheep, ducks, and growing vegetables. This produced an income which was sufficient to put Bastiat into the top 5% of tax payers which qualified him to vote in elections and to stand for election (which he did unsuccessfully in 1831 and 1832). During the July Monarchy (1830–1848) only about 200,000 to 240,000 of the wealthiest taxpayers were permitted for vote in elections, a group of people Bastiat referred to as “la classe électorale” (the electoral or voting class).[2] This restriction on voting was overturned after the Revolution in February 1848 when universal manhood suffrage was reintroduced. Nevertheless, the region’s economy had been hit hard (especially the export of wine and beef) because of Napoléon’s economic blockade (1806–14) of British trade and the reintroduction of high tariffs with the Restoration of the Bourbon monarchy in 1815. These policies badly affected the region as it was heavily dependent on wine and other agricultural exports for income. It appears that from the very beginning Bastiat opposed high tariffs and taxes and any government which strayed beyond very strict and defined limits to their activities.

During the July Revolution of 1830 which brought King Louis Philippe to power, Bastiat showed his liberal sympathies and sided with the revolution by persuading the officers of the Bayonne garrison to do so as well, thus tipping the balance of power in the south towards the new king. He wrote an amusing account of his actions in a letter to his friend and neighbour Félix Coudroy in which he describes how he drank wine and sang political songs with the officers as he persuaded them to support the revolution.[3] Although he was a staunch republican he believed a constitutional monarch as Louis Philippe promised to be was the best France could hope for in the circumstances. In one of his earliest political statements, written in Nov. 1830 in support of a local candidate, Bastiat warns his fellow voters that government has a tendency to always expand its sphere of action, increase the number of bureaucrats, and impose new and higher taxes.[4] Bastiat benefited from the new regime almost immediately. In May 1831 he was appointed Justice of the Peace in the canton of Mugron in spite of not having any formal legal training, perhaps as a reward for siding with the Revolution. In 1833 the new government introduced elections for the Departmental Council. In November of that year Bastiat (aged 32) was elected to the 28 member General Council of Les Landes, based in the town of Mont-de-Marsan (1841 population 4,465), which administered the affairs of the Département, such as tax collection, roads and other public works, education, and welfare relief for the poor. Bastiat brought a high level of economic expertise to the Council’s deliberations which he demonstrated in many memos and position papers which he submitted to them.

Bastiat, his close friend and neighbour Félix Coudroy, and other locals were members of a reading group or salon in Mugron, known as “The Academy”, where they discussed books, newspapers, and local politics. We know from his correspondence[5] that Bastiat was reading deeply in economics and social theory at this time, especially the works of Charles Comte (1782–1837) and Charles Dunoyer (1786–1862), who were trained as lawyers and became journalists who were active in opposing political repression in the closing years of the Napoleonic Empire and the early years of the Restoration. Their discovery of the economic ideas of Jean-Baptiste Say (1767–1832) had a profound impact on them and the new theory of liberalism known as “industrialism”[6] which they developed in many works during the 1820s and 1830s in turn had a profound impact on Bastiat during this formative period of his life.

In the second half of 1840 Bastiat tried to branch out into the insurance business. He spent 5 months or so in Madrid and Lisbon pursuing business contacts (his grandfather had done business in Spain and Bastiat spoke Spanish) and attempted to set up a business. This ultimately came to nothing, so he returned to farming in Mugron.

This local interest and political activity explains the topics of his earliest economic writings which he published in local papers, such as La Chalosse, Sentinelle des Pyrénées, Mémorial bordelais, and the Journal des Landes, and presented as memoranda he wrote for consideration by the General Council of Les Landes. These included articles on the establishment of a new secondary school in Bayonne (1834)[7] - he opposed the teaching of Latin and urged the teaching of modern languages and economically useful subjects like science; support for refugees from Poland (1834–35)[8] - he opposed the government’s severe restrictions on the movement and employment of the refugees; the financing and construction of canals (1837)[9] and railways in the region (1846)[10] - he was interested in properly assessing the economic impact of such large public works and criticised the way in which politics intruded into deciding routes; consumption taxes and tariffs on wine (1841, 1843)[11] - he believed that the unequal and heavy burden of taxes and tariffs on Les Landes’ main source of income was severely hampering its economic development; postal reform (1844, 1846)[12] - like Cobden and the Anti-Corn Law League in England, Bastiat wanted to see radical reform of the post office which would cut the cost of sending mail (the “penny post”) and open the business up to competition; the impact of the land tax on local communities (1844)[13] - Bastiat opposed the way the land tax burden was divided among the different regions of Les Landes which did not take into account changes in economic development or population growth and decline; and the general question of tariffs and custom duties (1834).

Bastiat’s interest in free trade can be seen as early as March 1829 when in a letter to his friend Victor Calmètes he expressed an interest in writing a book on “trade restrictions.”[14] The first thing he wrote on it was some “Reflections on the Petitions from Bordeaux, Le Havre, and Lyons Relating to the Customs Service” (April 1834) in which he expressed strong free trade opinions which he continued to voice for the rest of his life.[15] He became aware of Richard Cobden and the Anti-Corn Law League (which had been founded in Manchester in 1838) in May 1843 when he wrote a series of short articles for a local newspaper[16] explaining to French readers what was happening across the Channel and by mid–1844 he had become so immersed in the matter he had translated a large number of ACLL tracts and parliamentary speeches, which would become his first book on Cobden and the League (July 1845).[17] His own thoughts on how and why France should adopt a policy of free trade was written over the summer of 1844 and became his break-through essay[18] which got him admitted into the Parisian circle of political economists and launched a new career for him as a free rade activist and budding economic theorist.

His writings on economics from this early period show considerable skill in collecting and handling economic data and a growing confidence in making arguments based upon his understanding of economic theory.

This period lasted until the summer and fall of 1844 when his attention increasingly turned away from his village of Mugron towards London and Paris and he began to focus his reading and research on free trade. This resulted in him coming into personal contact with Richard Cobden in England and the free market economists in Paris who published his first article in the Journal des Économistes in October 1844 on French and English tariff policy.[19] This began the second major period in his life as the head of the French Free Trade movement.

Endnotes-

For information about Bastiat’s life see Jacques de Guenin and Jean-Claude Paul-Dejean, “General Introduction” to The Collected Works of Frédéric Bastiat, Vol. 1: The Man and the Statesman (2011); Dean Russell, Frédéric Bastiat: Ideas and Influence (Irvington-on-Hudson, N.Y.: Foundation for Economic Education, 1969); George Charles Roche, III, Frédéric Bastiat: A Man Alone (New Rochelle, N.Y.: Arlington House, 1971); Robert Leroux, Political Economy and Liberalism in France: The Contributions of Frédéric Bastiat (London: Routledge, 2011); and Gérard Minart, Frédéric Bastiat (1801–1850). Le croisé de libre-échange (Paris: L'Harmattan, 2004). ↩

-

See T.129 “The People and the Bourgeoisie”, Le Libre-Échange, 22 May 1847, in CW3, pp. 281–87. ↩

-

Letter 18 to Félix Coudroy, Bayonne 5 Aug. 1830, in CW1, pp. 28–30 and Early Writings. ↩

-

T.2 “To the Electors of the Department of Les Landes” (November, 1830), CW1, pp. 341–52 and in Early Writings. ↩

-

See in particular, Charles Dunoyer, L’Industrie et la morale considérées dans leurs rapports avec la liberté (Paris: A. Sautelet et Cie, 1825). On Comte, Dunoyer, and Say see, Leonard P. Liggio, “Charles Dunoyer and French Classical Liberalism,” Journal of Libertarian Studies, 1977, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 153–78; Mark Weinburg, "The Social Analysis of Three Early 19th Century French Liberals: Say, Comte, and Dunoyer, Journal of Libertarian Studies, 1978, vol. 2. no. 1, pp. 45–63; and David M. Hart, Class Analysis, Slavery and the Industrialist Theory of History in French Liberal Thought, 1814–1830: The Radical Liberalism of Charles Comte and Charles Dunoyer (unpublished PhD, King’s College Cambridge, 1994) Available online. ↩

-

T.3 “On Founding a New School” (1834), CW1, pp. 415–19and Early Writings. ↩

-

T.4 “On a Petition in favor of Polish Refugees) (1834) and ”Letter to an unidentified Friend in Defence of a Refugee" (Sept. 1835) in CW4 (forthcoming). ↩

-

T.7 “The Canal beside the Adour” (June-Aug. 1837) in CW4 (forthcoming). ↩

-

T.66 “On the Railway between Bordeaux and Bayonne” (19 May 1846), CW1, pp. 312–16. ↩

-

T.12 “The Tax Authorities and Wine” (January 1841), CW2, pp. 10–23 and Early Writings; and T.13 “Memoir on the Wine-Growing Question” (January 1843), CW2, pp. 25–42 and Early Writings. ↩

-

T.18 “Postal Reform” (August, 1844) and again later T. 58 (April, 1846), in CW4 (forthcoming). ↩

-

T.17 “On the Division of the Land Tax in the Department of Les Landes” (c. 1844) in CW4 (forthcoming). ↩

-

Letter 15. Mugron, 12 March 1829. To Victor Calmètes (OC1, p. 10) [CW1, p. 24]. ↩

-

T.5 “Reflections on the Petitions from Bordeaux, Le Havre, and Lyons Relating to the Customs Service” (April 1834), CW2, pp. 1–9 and Early Writings. ↩

-

T.266 (1843.05.18) “Free Trade. State of the Question in England. 1st Article”, La Sentinelle des Pyrénées, 18 May 1843. 3 articles published 18 May to 1 June 1843. [JCPD][CW6]. ↩

-

Bastiat, T.27 Cobden et la Ligue, ou l'agitation anglaise pour la liberté du commerce (Paris: Guillaumin, 1845). ↩

-

T.19 "On the Influence of French and English Tariffs on the Future of the Two People", Journal des Économistes, October 1844. (CW6 forthcoming) ↩

-

Bastiat, T.19 "De l’influence des tarifs français et anglais sur l’avenir des deux peuples" (On the Influence of French and English Tariffs on the Future of the Two People), Journal des Économistes, T. IX, Oct. 1844, pp. 244–71 in CW6 (forthcoming). ↩

Correspondence↩

Letter 1. Bayonne, 12 Sept. 1819. To Victor Calmètes↩

SourceLetter 1. Bayonne, 12 Sept. 1819. To Victor Calmètes (OC1, pp. 1-2) [CW1, pp. 11-12]

Text... My friend, we are in the same boat. Both of us are attracted to intellectual activity rather than the kind to which duty calls us, the difference being that the reflection which takes our fancy is closer to that of a lawyer than to that of a trader.

You know that I mean to go into commerce. When I entered the world of business, I conceived of business as purely mechanical and thought that six months would be enough to make me a trader. This being so, I did not think it necessary to work very hard and I concentrated in particular on the study of philosophy and politics.

I have since lost any illusions I had on this point. I now recognize that the science of commerce is not enclosed within the limits of routine. I have learned that a good trader, in addition to knowing his merchandise and where it comes from, and knowing the worth of what he can exchange, and bookkeeping, all of which experience and routine can teach in part, must also study the law and broaden his knowledge of political economy, which is not part of routine and requires constant study.

These considerations caused me considerable perplexity. Should I continue to study philosophy, which I like, or should I plunge into finance, [12] which I dread? Should I sacrifice my duty to my inclination or my inclination to my duty?

Having decided to put my duty before everything, I was about to start my studies when I thought of taking a look at the future. I weighed up the wealth I might hope to gain and balanced it against my needs and ascertained that whatever small happiness commerce might afford me, I might, while still a young man, free myself of the burden of work that would not make for my happiness. You know my tastes, you know whether, if I were able to live happily and peacefully, however little my wealth exceeded my needs, I would choose to impose the burden of a boring job on myself for three quarters of my life in order to possess a pointless surplus for the rest of my life.

... So now you know. As soon as I have acquired a certain prosperity, which I hope will be soon, I will be giving up business.

Letter 2. Bayonne, 5 March 1820. To Victor Calmètes↩

SourceLetter 2. Bayonne, 5 March 1820. To Victor Calmètes (OC1, pp. 2-3) [CW1, pp. 12-13]

Text. . . I had read the Treatise on Political Economy by J. B. Say, an excellent and highly methodical work. Everything flows from the principle that riches are assets and that assets are measured according to utility. From this fertile principle, he leads you naturally to the most far-flung consequences so that, when you read this work, you are surprised, as when reading Laromiguière,2 at the ease with which you go from one idea to the next. The entire system passes before your eyes in its various forms and gives you all the pleasure that a sense of the obvious can provide.

One day when I was in quite a large gathering, a question of political economy was discussed in conversation, and everyone was talking nonsense. I did not dare to put my opinions forward too much, since they were so diametrically opposed to the conventional wisdom. However, as each objection forced me to go up a notch to put forward my arguments, I was soon driven to the core principle. This was when M. Say made it easy for me. We started from the principle of political economy, which my adversaries admitted to be just. It was easy for us to go on to the consequences and reach that which was the subject of the conversation. This was the point at which I perceived [13] the full merit of the method and I would like it to be applied to everything. Do you not agree with me?

Letter 3. Bayonne, 18 March 1820. To Victor Calmètes↩

SourceLetter 3. Bayonne, 18 March 1820. To Victor Calmètes (OC1, p. 3) [CW1, p. 13]

TextI entered into the world one step at a time, but I did not rush into it, and, in the midst of its pleasures and pains, when others, deafened by so much noise, forget themselves, if I can put it like that, in the narrow circle of the present, my vigilant soul was always looking over its shoulder, and reflection prevented it from letting itself be dominated. What is more, my taste for study has taken up a great deal of my time. I concentrated so much on it last year that this year I was forbidden to continue with it, following the painful complaint it caused me. . . .

Letter 4. Bayonne, 10 Sept. 1820. To Victor Calmètes↩

SourceLetter 4. Bayonne, 10 Sept. 1820. To Victor Calmètes (OC1, p. 4) [CW1, p. 13]

Text. . . . . . .

One thing that occupies me more seriously is philosophy and religion. My soul is full of uncertainty and I cannot bear this state. My intellect rejects faith while my heart hankers after it. In fact, how can my intellect reconcile the great ideas about the Divine with the puerility of certain dogmas; and on the other hand, how can my heart not want to find rules of conduct in the sublime moral code of Christianity? Yes, if paganism is the mythology of the imagination, Catholicism is the mythology of sentiment. What could be more likely to interest a sensitive heart than the life of Jesus, the morality of the Gospels, and meditation on Mary? How touching all this is. . . .

Letter 5. Bayonne, Oct. 1820. To Victor Calmètes↩

SourceLetter 5. Bayonne, Oct. 1820. To Victor Calmètes (OC1, pp. 4-5) [CW1, pp. 13-14]

TextI must admit, my dear friend, that the subject of religion fills me with hesitation and uncertainty, which is beginning to become a burden. How can I not see the dogmas of our Catholicism as mythology? And in spite of it all, this mythology is so beautiful, so consoling, so sublime that error is almost preferable to truth. I have a feeling that if I had one spark of faith in my heart, it would shortly become a flame. Do not be surprised at what [14] I am saying to you here. I believe in God and the immortality of the soul, that virtue is rewarded and vice chastised. This being so, what a huge difference there is between a religious person and an unbeliever! My state is unbearable. My heart burns with love and gratitude to God and I do not know how to pay him the tribute of homage I owe Him. He occupies my thoughts only vaguely, while a religious man has before him a career that is fully marked out for him to pursue. He prays. All the religious ceremonies keep him constantly occupied with his Creator. And then this sublime reconciliation between God and man, this redemption, how sweet it must be to believe it! What an invention it is, Calmètes, if it is one!

Apart from these advantages, there is another which is no less important. The skeptic has to work out a moral code for himself and then follow it. What perfect understanding, what force of will he must have! And who is there to reassure him that tomorrow he will not have to change the ideas he holds today? A religious man, on the other hand, has his route fully mapped out before him. He takes nourishment from a moral code that is always divine.

Letter 6. Bayonne, 29 Apr. 1821. To Victor Calmètes↩

SourceLetter 6. Bayonne, 29 Apr. 1821. To Victor Calmètes (OC1, p. 5) [CW1, p. 14]

TextFor my part, I think that I am going to settle irrevocably on religion. I am tired of searches that lead and can only lead nowhere. There, I am sure of finding peace and I will not be tormented by fears, even if I make mistakes. What is more, it is such a beautiful religion that I can imagine that you can love it to such an extent that you obtain happiness in this life.

If I manage to make up my mind, I will take up my former pleasures again. Literature, English, and Italian will take up my time as in the past. My spirit has been numbed by books on controversy, theology, and philosophy. I have already reread a few tragedies by Alfieri. . . .

Letter 7. Bayonne, 10 Sept. 1821. To Victor Calmètes↩

SourceLetter 7. Bayonne, 10 Sept. 1821. To Victor Calmètes (OC1, pp. 5-6) [CW1, pp. 14-15]

TextI want to let you have a word on my health. I am changing my way of life, I have abandoned my books, my philosophy, my devotion, my melancholy, in a word my spleen, and I am all the better for it. I am getting out in the world and it is singularly amusing. I feel the need for money, which makes [15] me keen to earn some, which gives me a taste for work, which leads me to spend the day quite pleasantly in the store, which, in the last analysis, is extremely beneficial to my mood and health. However, I sometimes regret the sentimental enjoyment to which nothing can be compared, the love of poverty, the taste for a retired and peaceful life, and I think that by indulging in a little pleasure, I have wanted only to wait for the moment to abandon it. Enduring solitude in society is a misconception and I am thankful that I have understood this in good time. . . .

Letter 8. Bayonne, 8 Dec. 1821. To Victor Calmètes↩

SourceLetter 8. Bayonne, 8 Dec. 1821. To Victor Calmètes (OC1, pp. 6-8) [CW1, pp. 15-16]

TextI was away, my dear friend, when your letter arrived in Bayonne, which has made my reply somewhat late. How pleased I was to receive this dear letter! The longer the time of our separation recedes from us the more tenderly I think of you and prize having a good friend all the more. I have found no one here to replace you in my heart. How fond we were of one another! For four years, we were not parted from one another for an instant. Often the uniformity of our way of life and the perfect harmony of our feelings and thoughts did not allow us to talk much. With any other, silent walks of such length would have been unbearable; with you, however, I was never tired and they left me nothing to want for. I know people who love one another just to show off their friendship, while we loved each other unobtrusively and frankly; we realized that our friendship was remarkable only when someone brought it to our attention. Here, dear friend, everyone loves me but I have no friend. . . .

. . . So, here you are, my friend, in your robes and mortarboard. I find it difficult to know whether you have the disposition for the task you have chosen. I know that you have a great deal of justice and sound judgment, but that is the least of your requirements. You also need ease of speech, but is it pure enough? Your accent is not likely to have improved in Toulouse nor got any better in Perpignan. Mine is still dreadful and will probably never change. You love studying and quite like discussion. I therefore think that you should now concentrate on the study of law, as these are notions that can be learned only by working, like history and geography, and later on the physical aspects of your profession. Grace, and noble and easy gestures, a certain veneer, the kind of glances and gestures of the hand, that indefinable something that will attract, warn, and carry people along. That is halfway to [16] success. Read the letters by Lord Chesterfield3 to his son on this subject. It is a book whose moral code I am far from approving, attractive as it is, but a true mind like yours will easily be able to set aside what is bad and profit from what is good.

For my part, it is not Themis4 but blind fortune that I have chosen or which has been chosen for me as a lover. However, I must admit, my ideas on this goddess have changed a great deal. This base metal is no longer so base in my eyes. Doubtless, it was a fine thing to see the Fabricii and Curii5 remaining poor when the only reward of robbery and usury was wealth, and doubtless Cincinnatus did well to eat broad beans and radishes, since he would have had to sell his inheritance and honor to eat more delicate dishes. But times have changed. In Rome, wealth was the fruit of chance, birth, and conquests; today, it is the reward only of work, industry,6 and economy. In these circumstances, it is nothing if not honorable. Only a real fool taken from secondary school would scorn a man who knows how to acquire assets with honesty and use them with discernment. I do not believe that the world is wrong in this respect when it honors the rich; its error is to honor indiscriminately the honest rich man and the rich scoundrel. . . .

Letter 9. Bayonne, 20 Oct. 1822. To Victor Calmètes↩

SourceLetter 9. Bayonne, 20 Oct. 1821. To Victor Calmètes (OC1, pp. 8-9) [CW1, pp. 16-17]

TextEveryone pursues happiness, everyone situates it in a certain condition of life and aspires to it. The happiness you attach to a retired life has perhaps no other merit than to be perceived from a great distance. I have loved solitude more than you have, I have sought it with passion and have enjoyed it, but if it had lasted a few months longer, it would have led me to the grave. Men, and especially young men, cannot live alone. They grasp things with too much ardor, and if their thought is not spread over a thousand varied objects, the one that absorbs them will kill them.

I would like solitude, but I would want to have it with books, friends, a [17] family, and material interests. Yes, interests my friend, do not laugh at this word; they bind people together and generate work. You may be sure that a philosopher, even if he were interested in agriculture, would soon be bored if he had to cultivate someone else’s land free of charge. It is interest that embellishes an estate in the eyes of its owner, which puts a value on the inventory, makes Orgon happy, and makes the Optimist say:

The chateau de Plainville is the most beautiful chateau in the world.

You appreciate that when I speak of returns or of interests, I do not mean that sentiment that is close to egoism.

To be happy, I would like, therefore, to own an estate in a lively country, especially in a country where old memories and long-standing habits would have given me a link with everything there. This is when you enjoy everything, this is the via vitalis.7 I would like to have as my neighbors or even as coinhabitants friends like you, Carrière, and a few others. I would like an estate which was not so large that I would be able to neglect it, nor so small that it would give me worries and deprivations. I would like a wife. . . . I am not going to draw her portrait, I rather feel that I would be incapable of doing it and I would myself be (I have no false modesty with you) my children’s teacher. They would not be bold as in towns, nor uncouth as in lightly populated areas. It would take too much time to go into the details, but I assure you that my plan has the supreme merit, that of not being romantic. . . .

Letter 10. Bayonne, Dec. 1822. To Victor Calmètes↩

SourceLetter 10. Bayonne, Dec. 1822. To Victor Calmètes (OC1, pp. 9-10) [CW1, pp. 17-18]

Text. . . . . . .

Yesterday, I was reading a tragedy by Casimir Delavigne entitled The Pariah.8 I am no longer used to making critical analyses, so I will not discuss this poem with you. What is more, I have abandoned the general tendency of French readers to look for transgressions of the rules in what they read rather than pleasure. If I enjoy what I read, I am not very critical of the work, since the interest is the most important of its attractions. I have noticed that the weak point of all modern tragedians is dialogue. In my view, M. Casimir [18] Delavigne, who is better at this than Arnault and Jouy, is far from being perfect. His dialogues are not short enough nor sufficiently consistent, but rather tirades and speeches which do not even relate to one another, and this is a fault that readers forgive the least easily since the work thus becomes less true to life and less plausible. I seem rather to be present at a discussion between two preachers or the advocacy of two barristers than listening to a sincere, lively, and unaffected conversation between two people. Alfieri excels in dialogue, I think, and Racine’s is also very simple and natural. For the rest, carried along by a lively interest (which perhaps is not sufficiently often suspended) I rather skimmed than read The Pariah. Its versification seemed to me to be fine and rather too metaphorical if the characters were not Eastern. But the disaster was rather too easy to predict and from the beginning the reader is not in suspense.

Letter 11. Bayonne, 15 Dec. 1824. To Félix Coudroy↩

SourceLetter 11. Bayonne, 15 Dec. 1824. To Félix Coudroy (OC1, pp. 14-16) [CW1, pp. 18-19]

TextI note with pleasure that you are fervently studying English, my dear Félix. As soon as you have overcome the initial difficulties, you will find in this language a font of resources because of the great number of works it possesses. Apply yourself above all to translation and fill your storehouse with words and the rest will follow. At school I had a notebook and folded the pages in two; on one side I wrote all the English words I did not know and on the other the corresponding French ones. This method enabled me to stamp the words more effectively in my head. When you have finished Paul et Virginie,10 I will send you some other things; in the meantime I will note here a few lines of Pope to see if you can translate them. I must confess that I doubt this, since it was a long time before I reached this stage.

I am not surprised that studying is so attractive to you. I would also like it a lot if other uncertainties did not torment me. I am still like a bird on the [19] branch, since I do not want to do anything to displease my parents, but as long as this continues I will be setting aside any ambitious projects and will continue with solitary study.

- Let us (since Life can little more supply

- Than just to look about us, and to die)

- Expatiate free o’er all this scene of man.11

I should not be afraid that study will not be enough to quench my ardor, since I will stop at nothing less than acquiring knowledge of politics, history, geography, mathematics, mechanics, natural history, botany, four or five languages, etc., etc.

I must tell you that, since my grandfather became subject to attacks of fever, his mind is disturbed and consequently he does not want to see any member of his family go too far away. I know that I would worry him considerably if I went to Paris, and this being the case I can see that I will abandon the idea since the last thing in the world I wish to do is to cause him pain. I am fully aware that this sacrifice is not that of a fleeting pleasure but one affecting the usefulness of my entire life, but in the end I am determined to make it to avoid hurting my grandfather. On the other hand, I do not, just for a few business reasons, wish to continue the type of life I live here, and consequently I am going to suggest to my grandfather that I settle permanently in Mugron. There again I fear a snag, that people will want me to take over part of the administration of the estate, which means that I will find in Mugron all of the disadvantages of Bayonne. I am not at all suited to sharing administration. I want to do it all or none of it. I am too gentle to dominate and too vain to be dominated. But in the end I will lay down my conditions. If I go to Mugron, it will be to concentrate only on my studies. I will drag along as many books as I can, and I do not doubt that after a little time I will come to take a great deal of pleasure in this type of life.

Letter 12. Bayonne, 8 Jan. 1825. To Félix Coudroy↩

SourceLetter 12. Bayonne, 8 Jan. 1825. To Félix Coudroy (OC1, pp. 16-17) [CW1, pp. 19-21]

TextI am sending you the preceding pages, my dear Félix, which will be a constant proof that I am not neglecting to reply to you but merely to forward [20] the letter. I have this unfortunate fault resulting from my untidy habits which means that I believe that I have done my duty to my friends when I write to them, without thinking that the letter itself has to be sent.

You talk to me about political economy as though I knew more about it than you. If you have read Say carefully, as you appear to have done, I can assure you that you will have left me far behind, since I have read only the following four works on this subject, Smith,12 Say, Destutt, and Le Censeur. What is more, I have never studied M. Say in depth, especially the second volume, which I have just glanced through. You have given up hope that sane ideas on this subject will ever penetrate public opinion, but I do not share your despair. On the contrary, I believe that the peace that has reigned in Europe for the last ten years has spread them a great deal, and it is a good thing perhaps that this progress is slow and imperceptible. The Americans in the United States have very sound ideas on these matters, although they have set up customs stations in retaliation. England, which is always at the head of civilization in Europe, is now giving a good example by gradually giving up the system that hampers it.13 In France, commerce is enlightened but owners are less so, and manufacturers work just as hard to retain their monopolies. Unfortunately, we do not have a chamber capable of ascertaining the true state of the nation’s understanding. The seven-year period14 is also detrimental to this slow and upward drift of ideas from public opinion which partly rejuvenates the legislature. Finally, a few events and above all the incorrigible French character that enthuses about anything new and is always ready to treat itself to a few fine words will prevent the truth from triumphing for a short while. But I do not despair. The press, necessity, and financial interest will end up by achieving what reason still cannot. If you read Le Journal du commerce, you will have seen how the English government tries to enlighten itself by officially consulting the most enlightened traders and manufacturers. The conclusion then agreed is that the prosperity of Great Britain is not the product of the system it has followed but the result of many other [21] causes. It is not enough for two facts to exist at the same time to conclude that one is the cause and the other the effect. In England, trade restrictions and prosperity certainly relate to each other through coexistence and contiguity, but not through causation. England has prospered not because of, but in spite of, countless taxes. This is the reason I find the language of ministers so ridiculous when they say to us each year, “You see how rich England is, it pays a billion!”

I think that if I had more paper, I would continue this abstruse chatter. Farewell, with my fondest good wishes.

Letter 13. Bordeaux, 9 Apr. 1827. To Félix Coudroy↩

SourceLetter 13. Bordeaux, 9 Apr. 1827. To Félix Coudroy (OC1, pp. 18-20) [CW1, pp. 21-23]

TextMy dear Félix, as I have not yet decided when I will be returning to Mugron, I want to break the monotony of my absence with the pleasure of writing to you and I will begin by giving you a few items of literary news.

First of all, I will tell you that MM Lamennais and Dunoyer (whose names are not habitually linked in this way) are still at the same point, that is to say, the former at his fourth volume and the latter at his first.15

In a newspaper entitled Revue encyclopédique, I read a few articles which I found interesting, including a very short study on the work of Comte16 (a study limited to a short expression of praise), considerations on insurance and in general on the applications of the calculation of probabilities, a speech by M. Charles Dupin on the influence of public education, and lastly an article by Dunoyer entitled “A Study of Popular Opinion,” to which the name of industrialism17 has been given.18 In this article, M. Dunoyer does not go back further than MM B. Constant and J. B. Say, whom he quotes as being the first political writers to have observed that the purpose of social activity is industry. To tell you the truth, these authors have not perceived the use that might be made of this observation. The latter has considered such industry only in the light of the production, distribution, and consumption of wealth and in his introduction he even defines politics as the science of the [22] organization of society, which seems to prove that, like eighteenth-century authors, he sees politics only as concerning the forms of government and not as the basis and purpose of society. As for M. B. Constant, after being the first to have proclaimed this truth, that the aim of society’s activity is to secure industry, he is so far from having made it the basis of his doctrine that his major work19 covers only forms of government, the checks and balances of political power, etc. etc. Dunoyer then moves on to an examination of Le Censeur européen, whose authors, once they had taken over the isolated observations of their predecessors, have made from them an entire corpus of doctrine which is discussed with care in this article. I cannot analyze an article for you that is itself just an analysis. I will tell you, however, that Dunoyer seems to me to have reformed a few of the opinions that were predominant in Le Censeur. For example, I think that he is now giving the word industry a more extended meaning than before, since he includes in this word any work that tends to improve our faculties; thus any useful and legitimate work counts as industry and any man who takes part in it, from the head of the government to an artisan, is a producer.20 From this it follows that Dunoyer continues to think as before that, in the same way that hunting peoples select their most skillful hunter to be their leader, and warlike peoples the most intrepid warrior, industrious peoples should also summon to the helm of public affairs those men who have most distinguished themselves in industry. However, he thinks that he has made a mistake in individually naming the branches of production from which the choice of rulers should be made and in particular, agriculture, commerce, manufacturing, and banking, for although these four sectors doubtless cover the majority of the huge circle of industry, they are not the only ones through which men hone their faculties by means of work and several others appear even more suited to training legislators, such as those of jurist and man of letters.

I have discovered a real treasure in a slim volume containing a mixture of moral and political writings by Franklin.21 I am so keen on this that I have started to use the same means as he to become as good and happy as he. [23] However, there are some virtues that I will not even seek to acquire since they appear to be quite unattainable in my case. I will bring you this small work.

I have also come across by chance a very detailed article on beet sugar. Its authors have calculated that it would cost the manufacturer ninety centimes a pound, where cane sugar sells at one franc ten centimes. You can see that, assuming total success, it would leave not much of a margin. What is more, to devote oneself with pleasure to this type of work and perfect it, you would need a knowledge of chemistry, which unfortunately is totally foreign to me. Be that as it may, I was bold enough to write a letter to M. Clément. Lord only knows whether he will reply.

For the sum of three francs a month, I am attending a course in botany three times a week. We cannot learn much there, as you can see, but apart from passing the time, it is useful in putting me in touch with the people who are concerned with science.

This is just chatter; if it did not cost you so much to write, I would ask you to reciprocate by return.

Letter 14. Mugron, 3 Dec. 1827. To Félix Coudroy↩

SourceLetter 14. Mugron, 3 Dec. 1827. To Félix Coudroy (OC1, pp. 20-21) [CW1, p. 23]

Text. . . You are encouraging me to carry out my project, and I do not think I have ever in my life been so determined. From the start of 1828, I will use my time in removing the obstacles, the most considerable of which are pecuniary. Going to England, renovating my house, purchasing the livestock, instruments, and books I need, organizing the financing for wages and seed, all for a small sharecropping farm (because I want to start with just one), I feel will carry me a bit far. It is clear to me that in the first two or three years, my agriculture will not produce much, both because of my inexperience and because the crop rotation I propose to adopt will show its full effect only in due course. However, I am very happy with my situation since, if I did not have enough to live on and a bit more from my little property, it would be impossible to undertake such an enterprise; for as I can sacrifice the income from my property, if need be, nothing prevents me from doing what I want. I read books on agriculture and nothing equals the beauty of this working life, because it has everything, but it requires knowledge that is foreign to me, such as natural history, chemistry, mineralogy, mathematics, and many other things.

Farewell, my dear Félix, good luck and return soon.

Letter 15. Mugron, 12 March 1829. To Victor Calmètes↩

SourceLetter 15. Mugron, 12 March 1829. To Victor Calmètes (OC1, p. 10) [CW1, p. 24]

Text. . . . . . .

On this subject, do you know that I am intending to go into print in my lifetime? What, I can hear you say, Bastiat an author? What is he going to give us? A collection of ten or twelve tragedies? An epic? Or perhaps some madrigals? Will he follow in the footsteps of Walter Scott or Lord Byron? None of these things, my friend; I have limited myself to gathering together the heaviest forms of reasoning on the heaviest of questions. In a word, I am dealing with our system of trade restrictions. See if that tempts you, and if so I will send you my complete works, once, of course, they have been given the honor of being printed. I wanted to tell you more about this, but I have too much else to say to you. . . .22

Letter 16. Mugron, Jul. 1829. To Victor Calmètes↩

SourceLetter 16. Mugron, July 1829. To Victor Calmètes (OC1, pp. 10-11) [CW1, pp. 24-25]

Text. . . I am pleased to see that we have nearly the same opinion. Yes, as long as our deputies want to further their own business and not that of the general public, the public will remain just the tail end of the people in power. However, in my opinion, the evil comes from further afield. We easily surmise (since it suits our amour propre) that all evil results from power; on the contrary, I am convinced that its source is the ignorance and inertia of the masses. What use do we make of the rights given to us? The constitution tells us that we will pay what we consider appropriate and authorizes us to send our representatives to Paris to establish the amount which we wish to hand over in order to be governed; we then give our power of attorney to people who are beneficiaries of taxation. Those who complain about the prefects are themselves represented by them. Those who deplore the wars of sympathy23 we are waging in the east and the west, sometimes in favor of freedom for a people, sometimes to put another into servitude, are themselves represented by army generals. We expect prefects to vote for their own [25] elimination and men of war to become imbued with pacifist ideas!24 This is a shocking contradiction. But, men will say, we expect from our deputies dedication and self-renunciation, virtues from classical times which we would like to see resurrected in our midst. What a puerile illusion! What sort of policy can be based on a principle distasteful to human organization? At no time in history have men ever renounced themselves, and in my view it would be a great misfortune if this virtue took the place of personal interest. If you generalize self-renunciation in public opinion, you will see society destroyed. Personal interest, on the other hand, leads to individuals bettering themselves and consequently the masses, which are made up solely of individuals. It will be alleged, pointlessly, that the interest of one man is opposed to that of another; in my opinion this is a serious, antisocial error.25 And, if we may progress from general notions to their application, if taxpayers are themselves represented by men with the same interests as they, reforms will occur by themselves. There are some who fear that the government would be destroyed by a spirit of economy, as though each person did not feel that it was in his interest to pay for a force responsible for the repression of evildoers.

I embrace you warmly.

Letter 17. Bayonne, 4 Aug. 1830. To Félix Coudroy↩

SourceLetter 17. Bayonne, 4 Aug. 1830. To Félix Coudroy (OC1, pp. 21-24) [CW1, pp. 25-28]

TextMy dear Félix, I am so over the moon I can scarcely hold my pen. It is not a question here of a slave revolt, the slaves indulging in greater excesses, if that is possible, than their oppressors. It is enlightened men who are rich [26] and prudent who are sacrificing their interests and their lives to establishing order and its inseparable companion, freedom. Let people tell us after this that riches weaken courage, that enlightenment leads to disorganization, etc., etc. I wish you could see Bayonne. Young people are carrying out all forms of service in the most perfect order; they are receiving and sending out letters, mounting guard, and are acting as local, administrative, and military authorities all at once. Everyone is working together, townsmen, magistrates, lawyers, and soldiers. It is an admirable spectacle for anyone who is capable of seeing it, and if I used to be only half committed to the Scottish persuasion,27 I would be doubly so today.

A provisional government28 has been set up in Paris, made up of MM Laffitte, Audry-Puiraveau,29 Casimir Périer, Odier, Lobeau, Gérard, Schonen, Mauguin, and La Fayette as the commander of the National Guard, which is more than forty thousand men. These people could make themselves dictators; you will see that they will do nothing to enrage those who have no belief in either good sense or virtue.

I will not go into detail on the misfortunes which the terrible Praetorian guards, known as royal guards, have inflicted on Paris. Sixteen regiments of these men, greedy for power, roamed the streets, cutting the throats of men, children, and old men. It is said that two thousand students lost their lives there. Bayonne is mourning the loss of several of its sons; on the other hand, the gendarmerie, the Swiss mercenaries, and bodyguards were crushed the next day. This time, the regular infantry, far from remaining neutral, fought vigorously for the nation. However, we still have to mourn the loss of twenty thousand brothers who died to secure liberty30 and benefits for us which they will never enjoy. I heard the hope for these frightful massacres expressed in our circle;31 the person who expressed it must feel satisfied.

The nation was led by a crowd of deputies and peers of France, including [27] generals Sémélé, Gérard, La Fayette, Lobeau, etc., etc. Despotism had entrusted its cause to Marmont, who, it is said, has been killed.

The École polytechnique has suffered greatly and fought bravely.

At last, calm has been restored and there is no longer a single soldier in Paris; this great town, following three consecutive days and nights of massacres and horror, is governing itself and governing France, as if it were in the hands of statesmen. . . .

It is fair to proclaim that the regular troops supported the national will everywhere. Here, a hundred and forty-nine officers met to deliberate. One hundred and forty-eight swore that they would break their swords and tear off their epaulettes rather than massacre a people just because they do not wish to be oppressed. In Bordeaux and Rennes, their conduct was the same, which reconciles me somewhat to the law of recruitment.

The National Guard is being organized everywhere and three major advantages are expected. The first is to prevent disorder, the second to maintain what we have just acquired, and the third to show other nations that while we do not wish to conquer others, we are ourselves impregnable.

Some believe that to satisfy the desires of those who consider that France can exist only as a monarchy the crown will be offered to the duc d’Orléans.32

For my part, my dear Félix, I was pleasantly disappointed; I came looking for danger, I wanted to conquer with my fellow men or die with them, but I found only laughing faces and, instead of the roar of cannon, I heard only outbursts of joy. The population of Bayonne is admirable for its calm, energy, patriotism, and unanimity, but I think I have already told you that.

Bordeaux has not been so fortunate. There were a few excesses. M. Curzay seized the letters of office.33 On the 29th or 30th, of the four young men who were sent to claim them back as a sacred property, one was run through by his sword and he wounded another. The two others threw him to the crowd, who would have massacred him had the constitutionalists not pleaded for him.

Farewell, I am tired of writing and must be forgetting many things. It is midnight and for the last week I have not slept a wink. At least today, we can indulge ourselves in sleep.

[28]There is talk of a movement of four Spanish regiments on our border. They will be well received.

Letter 18. Bayonne, 5 Aug. 1830. To Félix Coudroy↩

SourceLetter 18. Bayonne, 5 Aug. 1830. To Félix Coudroy (OC1, pp. 24-27) [CW1, pp. 28-30]

TextMy dear Félix, I will not talk any more about Paris to you as the newspapers will inform you of all that is going on. Our cause is triumphing, the nation is admirable, and the people will be happy.

Here the future appears to be darker. Fortunately, the question will be decided this very day. I will scribble the result for you in the margin.

This is the situation. On the 3rd, many groups were gathered in the square and were discussing, with extraordinary exaltation, whether we should not immediately take the initiative of displaying the tricolor flag. I moved about without taking part in the discussions, as whatever I said would have had no effect. As always happens, when everyone talks at once, no one does anything and the flag was not displayed.

The following morning, the same question was raised. The soldiers were still well disposed to let us act, but during the hesitation, dispatches arrived for the colonels and obviously cooled down their zeal for the cause. One of them even cried out in front of me that we had a king and a charter and that we ought to be faithful to them, that the king could not do wrong, that his ministers were the only guilty ones, etc., etc. He was replied to roundly . . . but this repeated inaction gave me an idea which, by dint of my turning it over in my mind, got so ingrained there that since then I have not thought till now of anything else.

It became clear to me that we had been betrayed. The king, I said to myself, can have one hope only, that of retaining Bayonne and Perpignan; from these two points, he would raise the Midi and the west and rely on Spain and the Pyrenees. He could foment a civil war in a triangle whose base would be the Pyrenees and the summit Toulouse, with the two angles being fortresses. The country it comprises is the very home of ignorance and fanaticism; one side of it touches Spain, the second the Vendée, and the third Provence. The more I thought about it, the clearer this project became. I told my most influential friends about it but they, inexcusably, had been summoned at the citizens’ pleasure to take charge of various organizations and no longer had time to think of serious matters.

Other people had had the same idea as I, and by dint of shouting and [29] repetition it became general. But what could we do when we were unable to deliberate and agree, nor make ourselves heard? I withdrew to reflect and conceived several projects.

The first, which was already that of the entire population of Bayonne, was to display the flag and endeavor, through this movement, to win over the garrison of the chateau and the citadel. This was done yesterday at two o’clock in the afternoon, but by old people who did not attach the same significance to it as Soustra, I, and a lot of others, with the result that this coup failed.

I then took my papers of authorization to go to the army encampment to look for General Lamarque. I was relying on his reputation, his rank, his character as a deputy and his eloquence to win over the two colonels and, if need be, on his vigor to hold them up for two hours and present himself at the citadel in full military dress, followed by the National Guard with the flag at their head. I was on the point of mounting my horse when I received word that the general had left for Paris, and this caused the project, which was undoubtedly the surest and least dangerous, to fail.

I immediately had a discussion with Soustra, who unfortunately was occupied with other cares, telegraphic dispatches, the soldiers’ encampment, the National Guard, etc., etc.; we went to find the officers of the 9th, who have an excellent spirit, and suggested that they seize the citadel; and we undertook to lead six hundred resolute young men. They promised us the support of their entire regiment, after having, in the meantime, deposed their colonel.

Do not say, my dear Félix, that our conduct was imprudent or frivolous. After what has happened in Paris, what is most important is that the national flag should fly over the citadel in Bayonne. Without that, I can see civil war in the next ten years, and, although I do not doubt the success of the cause, I would willingly go so far as to sacrifice my life, an attitude shared by all my friends, to spare our poor provinces from this fearful scourge.

Yesterday evening, I drafted the attached proclamation to the 7th Light, who guard the citadel, as we intended to have it delivered to them before the action.

This morning, when I got up, I thought that it was all over; all the officers of the 9th were wearing the tricolor cockade, the soldiers could not contain their joy, and it was even being said that officers of the 7th had been seen wearing these fine colors. An adjutant had even shown me personally the positive order, given to the entire 11th division, to display our flag. However, hours went by and the banner of liberty was still not visible over the citadel. [30] It is said that the traitor J—— is advancing from Bordeaux with the 55th regulars. Four Spanish regiments are at the border, there is not a moment to lose. The citadel must be in our hands this evening or civil war will break out. We will act with vigor if necessary, but I, who am carried along by enthusiasm without being blind to the facts, can see that it will be impossible to succeed if the garrison, which is said to be imbued with a good spirit, does not abandon the government. We will perhaps have a few wins but no success. But we should not become discouraged for all that, as we must do everything to avoid civil war. I am resolved to leave straight away after the action, if it fails, to try to raise the Chalosse. I will suggest to others that they do likewise in the Landes, the Béarn, and the Basque country; and through famine, wiles, or force we will win over the garrison.

I will keep the paper remaining to me to let you know how this ends.

The 5th at midnight

I was expecting blood but it was only wine that was spilt. The citadel has displayed the tricolor flag. The military containment of the Midi and Toulouse has decided that of Bayonne; the regiments down there have displayed the flag. The traitor J—— thus saw that the plan had failed, especially as the troops were defecting on all sides; he then decided to hand over the orders he had had in his pocket for three days. Thus, it is all over. I plan to leave immediately. I will embrace you tomorrow.

This evening we fraternized with the garrison officers. Punch, wine, liqueurs, and above all, Béranger contributed largely to the festivities. Perfect cordiality reigned in this truly patriotic gathering. The officers were warmer than we were, in the same way as horses which have escaped are more joyful than those that are free.

Farewell, all has ended. The proclamation is no longer useful and is not worth the two sous it will cost you.

Letter 19. Bayonne, 22 Apr. 1831. To Victor Calmètes↩

SourceLetter 19. Bayonne, 22 Apr. 1831. To Victor Calmètes (OC1, p. 12) [CW1, pp. 30-31]

TextI am annoyed that a property qualification for eligibility34 should be an obstacle to your election or at least to your standing as a candidate. I have always thought that it was sufficient to require guarantees from electors, and [31] that that required from candidates is a disastrous duplication. It is true that deputies should be remunerated, but that is too close to the knuckle, and it is ridiculous that France, which pays everybody, should not remunerate its businessmen.

In the district in which I live, General Lamarque will be elected outright for the rest of his life. He has talent, probity, and a huge fortune. This is more than what is required. In the third district of the Landes, a few young people who share the opinions of the left have offered me the opportunity of being a candidate.35 As I have no remarkable talents, fortune, influence, or relations, it is certain beyond doubt that I would have no chance, especially as the movement is not very popular around here. However, as I have adopted the principle that the post of deputy should be neither solicited nor refused, I replied that I would not involve myself in it and that whatever the post my fellow citizens called on me to undertake, I was ready to devote my fortune and life to them. In a few days they should be holding a meeting at which they will decide on their choice of a candidate. If their choice falls on me, I admit that I would be overjoyed, not for myself, since apart from the fact that my definite nomination is impossible (if it occurred it would ruin me), but because I hanker today only for the triumph of principles, which are part of my existence, and that if I am not certain of my means, I am of my vote and my ardent patriotism. I will keep you informed. . . .

Letter 20. Bordeaux, 2 March 1834. To Félix Coudroy↩

SourceLetter 20. Bordeaux, 2 March 1834. To Félix Coudroy (OC1, pp. 27-28) [CW1, pp. 31-32]

Text. . . I have spent a little time getting to know a few people and will succeed in doing so, I hope. But here, on every face to which you are polite you see written “What is there to gain from you?” It is discouraging. It is true that a new newspaper is being founded. The prospectus does not tell you very much and the editor still less, since the first has been written with the pathos that is all the fashion and the second, assuming that I am a man of the party, limited himself to making me feel how inadequate Le Mémorial36 and L’Indicateur were for patriots. All that I was able to obtain was a great deal of insistence that I should take out a subscription.

[32]Fonfrède37 is perfectly in line with Say’s principles. He writes long articles which would be very good in a sustained work. I will take the risk of going to visit him.

I believe that a series of lectures would succeed here and I am tempted. I think that I would have the strength to do it, especially if one could start with the second session, since I admit that I could not answer at the first or even be able to read fluently, but I cannot thus abandon all my business affairs. We will see about it nevertheless this winter.

A teacher of chemistry has established himself here already. I dined with him without knowing that he gave classes. If I had known, I would have found out how many pupils he had, what the cost was, etc. I would have found out whether, with a history teacher, a teacher of mechanics, and a teacher of political economy a sort of Athenaeum could be formed. If I lived in Bordeaux, it would have been very unfortunate if I did not manage to set it up, even if I had to bear all the costs myself, since I am convinced that if a library were added, this establishment would succeed. Learn history, therefore, and we will perhaps try one day.

I will stop now; thirty drummers are practicing under my window and I cannot hear myself think.

Letter 21. Bayonne, 16 June 1840. To Félix Coudroy↩

SourceLetter 21. Bayonne, 16 June 1840. To Félix Coudroy (OC1, p. 29) [CW1, pp. 32-33]

TextMy dear Félix, I am still about to leave; we have booked our seats three times already and finally they have been booked and paid for Friday. We have been out of luck, for when we were ready, the Carlist General Balmaceda blocked the roads and it is to be feared that we will have difficulty in getting through. But you must not say anything so as not to worry my aunt, [33] who is already only too ready to fear the Spanish. For my part, I find that the business that is propelling us toward Madrid is worth taking a few risks for. Up to now, it has shown itself in a very favorable light. We would find the capital required here if we limited ourselves above all to founding just a Spanish company.39 Will we be stopped by the sluggishness of this nation? In this case, I will have to bear my traveling costs and will be compensated by the pleasure of having seen at close quarters a people whose qualities and faults distinguish it from all the others.

If I note anything of interest, I will take care to keep it in my wallet to let you know.

Letter 22. Madrid, 6 Jul. 1840. To Félix Coudroy↩

SourceLetter 22. Madrid, 6 July 1840. To Félix Coudroy (OC1, pp. 29-32) [CW1, pp. 33-35]

TextMy dear Félix, I have received your letter of the 6th. From what you tell me of my dear aunt, I see that for the moment she is in good health but she has been somewhat unwell; for me that is the reverse side of the coin. Madrid today is a theater that is perhaps unique in the world, which Spanish laziness and lack of interest are handing over to foreigners who, like me, have some knowledge of the customs and language of the country. I am certain that I could do excellent business here, but the idea of being away from my aunt at an age when her health is starting to become delicate, prevents me from thinking of announcing my exile.

Since I have set foot in this singular country, I have meant to write to you a hundred times. But you will excuse me for not having had the energy to do this when you learn that we devote the morning to business, the evening to an essential walk, and the day to sleeping and gasping under the weight of heat that is uncomfortable more because it is continuous than by reason of its intensity. I have forgotten what clouds look like, since the sky is perfectly clear and the sun fierce. You can rest assured, my dear Félix, that it is not through negligence that I have delayed writing to you, but I am really not suited to this climate and I begin to regret that we did not postpone our departure by two months. . . .