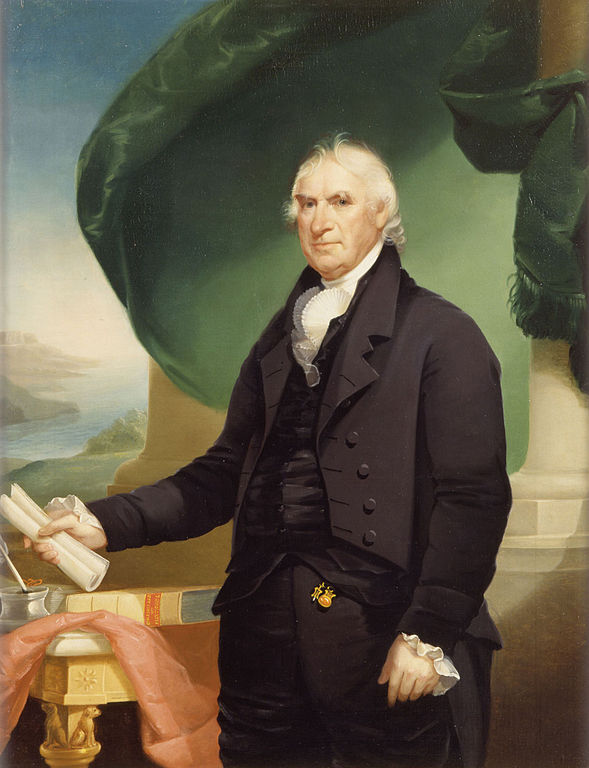

Clinton, George (1739–1812)

Source: This biographical essay was written by Quentin Taylor, Resident Scholar (2008-2009), Liberty Fund, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana.

Copyright: The copyright is held by Liberty Fund, Inc.

Fair Use: This material is put online to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. Unless otherwise stated in the Copyright Information section above, this material may be used freely for educational and academic purposes. It may not be used in any way for profit.

Clinton, George (July 26 1739 – April 20, 1812)

Clinton, George (July 26 1739 – April 20, 1812) military leader, governor of New York, and vice president of the United States, was born at Little Britain, Ulster County, New York, the son of Scots-Irish immigrants. Clinton received the rudiments of an education from a tutor before serving on a privateer during the French and Indian War. He later joined his brother’s militia company and participated in the capture of Montreal in 1760. Upon his return Clinton studied law in New York City, was admitted to the bar in 1764, and held a few minor posts in Ulster. In addition to practicing law, he worked as a surveyor and engaged in farming.

When new elections for the provincial assembly were held in 1768, the twenty-eight year old Clinton was chosen to represent Ulster. By this time tensions between the colonies and Parliament had erupted in violence and British troops were quartered in New York. Clinton was among the radicals who opposed the pro-British faction in the assembly and championed the colonial cause. Shortly before hostilities at Lexington and Concord, he moved that Parliament had no right to tax the colonies whatsoever. His efforts were rewarded with a seat in the extra-legal provincial assembly, which selected him to represent New York in the Second Continental Congress in May 1775. In Philadelphia he met George Washington and other leaders of the revolutionary movement. With Washington Clinton developed a warm friendship that survived both the war and post-war politics.

Before independence was declared, Clinton returned to New York to assume command of a militia brigade. In addition to pacifying loyalists and recruiting solders, his principal task was defending the Hudson valley from British attack. A capable and assertive leader, Clinton won the praise of the New York Convention and in March 1777 was commissioned a brigadier general in the Continental Army. In early October a superior British force assaulted Fort Montgomery, where Clinton led a stubborn, but futile defense. The heroic stand did frustrate the enemy’s designs and contributed to the surrender of General Burgoyne’s army at Saratoga later that month.

As he worked to buttress military defenses and quell mutinies in the army, Clinton simultaneously served as the Empire State’s first governor under its new constitution. Elected in 1777, he would serve six successive three-year terms and an additional term from 1801 to 1804. Energetic and patriotic, if not as brilliant as some of his counterparts, Clinton was the most popular man in the state, and ranks with John Hancock and Patrick Henry as the most notable governors of the early republic. The strong executive created by the New York Constitution made him among the most powerful as well. He was not, however, without political opposition or grave challenges in the post-war era. Vermont seceded from New York, former loyalists clamored for compensation, British soldiers occupied forts on the frontier, taxpayers demanded paper money, and a tariff proposed by Congress threatened to cut off a key source of revenue. While not always successful, Clinton invariably had popular support for his policies and managed to steer a moderate course in troubled times. He particularly appealed to the yeomanry of the rural counties, but was also attentive to the interests of the upper gentry and urban commercial classes.

Prior to peace with Great Britain in late 1783, Clinton had called for strengthening the powers of Congress in order to successfully prosecute the war. In 1781 he had approved a measure to create a federal impost or tariff that would give Congress an independent source of revenue. With the war coming to a close and its own revenues stretched, the New York legislature rescinded its approval and enacted a new state impost to supply its needs. Additional attempts to gain New York’s unconditional assent to a federal impost proved unsuccessful. Clinton supported the tariff in principle, but opposed entrusting collections and enforcement to national authorities.

The failure of the impost and related problems under the Articles of Confederation led to demands for general reform that culminated in the Philadelphia Convention of May 1787. Although suspicious of nationalists such as Alexander Hamilton, Clinton did not oppose sending delegates, confident that any plan which threatened New York’s interests would be rejected. His criticism of the Convention while it was still deliberating set off a war of words in the press, anticipating the partisan struggle over ratification that followed. The Constitution itself was assailed in a series of newspaper essays under the name of “Cato” that were widely attributed to Clinton. In addition to stressing the difficulty of maintaining a republic across an extensive territory, “Cato” faulted the Constitution for its vague grants of power and insufficient safeguards for liberty. He also identified specific deficiencies, including the federal regulation of elections, the continuance of the slave trade, and an unlimited power to tax. The popularity of “Cato” and his ilk led Hamilton to counter with The Federalist papers. When the New York ratifying convention finally met in Poughkeepsie on June 17, 1788, opponents of the Constitution, led by Clinton, made up a large majority. Within a week, news arrived that New Hampshire had become the ninth state to ratify, thus securing its adoption. Virginia’s ratification shortly thereafter prompted Clinton and others Antifederalists to work for conditional adoption that would have allowed New York to withdraw from the union if certain amendments were not added to the Constitution. In the end, this condition was dropped in lieu of a resolution calling for a second federal convention. With Clinton abstaining, the Constitution was adopted by the narrow margin of 30-27.

Thwarted in his attempt to become the nation’s first vice-president, Clinton did secure election to a fifth term as governor. Weakened by his opposition to the Constitution and restrained by a Federalist legislature, Clinton’s popularity declined to the point of political vulnerability. His narrow election to a sixth term was marred by irregularities, and in 1795, after eighteen years as governor, he stepped down. During his last term, the legislature wrested away the governor’s exclusive power to make nominations to key offices, significantly restricting his use of patronage. Around the same time, Clinton’s daughter, Cornelia, married the controversial French envoy “Citizen” Genêt.

In retirement Clinton pursued various private interests, particularly business matters. Like his friend Washington, he preferred to invest in real estate, and in time amassed a modest fortune. His business partners included the German entrepreneur, John Jacob Astor, who purchased part of Clinton’s Greenwich Village estate in 1805. After the death of his wife of thirty years in 1800, he reentered public life and was elected to a seventh and final term as governor. Jeffersonian in his approach to economics, Clinton opposed new taxes, state banks, and public debt. He did, however, support legislation for internal improvements and public education.

In 1804 Clinton was elected as Jefferson’s vice president, replacing fellow New Yorker Aaron Burr, whose fatal duel with Hamilton resulted in political exile. He silently opposed Jefferson’s embargo policy and lamented his neglect of the nation’s defenses. In 1808 Clinton sought the presidency, but lost the nomination to Jefferson’s secretary of state, James Madison. He agreed to serve as Madison’s vice president, but was even more critical of his policies than his predecessor’s. Clinton had little influence over either, but did defeat the re-chartering of the national bank with his tie-breaking vote in the Senate. Plagued by poor health in his last years, he was the first vice president to die in office.

Often remembered as a self-interested opponent of the Constitution, Clinton was among the most capable and accomplished leaders of the revolutionary era. Along with his honesty and patriotism, his ability to successfully lead New York through the perils of war and the uncertainties of peace entitle him to an esteemed place in America’s founding.