This first edition of an English translation of Lady Blennerhasset's Madame de Stael: Her Friends and Her Influence in Politics and Literature, which comes to the Liberty Fund archives through the Hamburger collection, seems a particularly appropriate book to highlight on le quatorze juillet as de Stael is best known for her writings on the French Revolution.

The Reading Room

Madame de Stael: From the Liberty Fund Rare Book Room

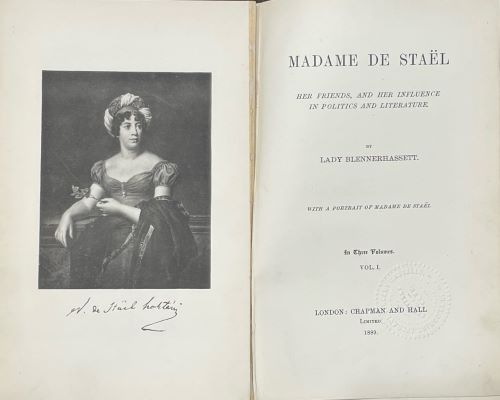

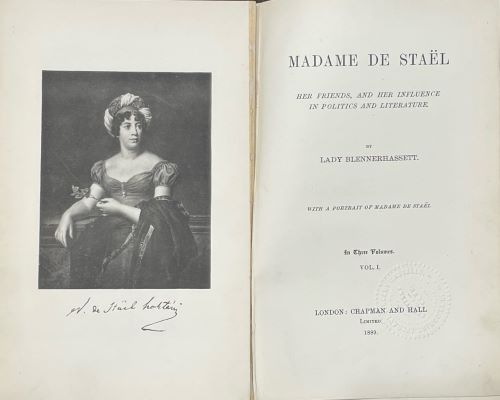

The book is carefully but not ornately bound in maroon cloth, with gilding on the spine. The Marie Eleonore Godefroid portrait of de Stael that is used for the frontispiece is the same that is used on the cover of Liberty Fund's edition of her Considerations on the French Revolution.

It's a simple book, in its presentation. But it is Blennerhassett's first significant historical work, and the figure she chose was a woman of enormous significance, whose charm, wit, and intellect are often forgotten today, but should be revisited more often.

Here is de Stael elegantly savaging Napoleon, for example:

It's a simple book, in its presentation. But it is Blennerhassett's first significant historical work, and the figure she chose was a woman of enormous significance, whose charm, wit, and intellect are often forgotten today, but should be revisited more often.

Here is de Stael elegantly savaging Napoleon, for example:

Far from recovering my confidence by seeing Bonaparte more frequently, he constantly intimidated me more and more. I had a confused feeling that no emotion of the heart could act upon him. He regards a human being as an action or a thing, not as a fellow-creature. He does not hate more than he loves; for him nothing exists but himself; all other creatures are ciphers. The force of his will consists in the impossibility of disturbing the calculations of his egoism; he is an able chess-player, and the human race is the opponent to whom he proposes to give checkmate. His successes depend as much on the qualities in which he is deficient as on the talents which he possesses. Neither pity, nor allurement, nor religion, nor attachment to any idea whatsoever could turn him aside from his principal direction. He is for his self-interest what the just man should be for virtue; if the end were good, his perseverance would be noble.

And here she is on Robespierre and the Committee of Public Safety.

This Committee was not composed of men of superior talent. The machine of terror, the springs of which had been prepared for action by events, exercised alone unbounded power. The government resembled the hideous [guillotine] employed on the scaffold; the axe was seen, rather than the hand which put it in motion. A single question was sufficient to overturn the power of these men… Their force was measured by the atrocity of their crimes and nobody dared attack them. These 12 members of the Committee of Public Safety distrusted one another, as the Convention distrusted them, and they distrusted it. The army, the people and the partisans of the revolution were all mutually filled with alarm.No name of this epoch will remain except Robespierre. He was neither more able nor more eloquent than the rest – but his political fanaticism had a character of calmness and austerity which made him feared by all his colleagues.... He [Robespierre] sent to the scaffold some as counter-revolutionists, others as ultra-revolutionists. There was something mysterious in his manner that caused an unknown terror to hover about in the midst of the visible terror that the government proclaimed. He never adopted the means of popularity then generally in use. ... Robespierre acquired the reputation of high democratic virtue and so was believed to be incapable of personal views. As soon as he was suspected of having them, his power was at an end.”

Blennerhassett's work helped ensure that de Stael's work was read and remembered by future generations. Liberty Fund's edition hopes to do the same.(It is worth, perhaps, noting that the book is also a reminder of a time when women writers were known by title--not Germaine, but Madame, de Stael. Not Charlotte, but Lady, Blennerhassett.)

Comments:

Walter Donway

A succinct, elegant introduction to this book. It now is on my list. It seems at times I have been mostly reading all my life but essentially without a plan. It would have behooved me, 50 years ago, to begin with a list of the 100 greatest/most influential/classic books (by some standard) and read two a year, whatever else I was reading. By now, I would be finished. Maybe I would be trying now to identify each year's most consequential book to read--projecting forward the spirit and standards of the 100 greatest. But exactly why does this seem important to me?