Finals week is upon us, and students everywhere are reviewing notes, writing papers, sitting exams, and hoping to remember enough of what they've read to succeed. Pierre Goodrich's copy of Charles Lamb's Essays of Elia opens a window into Goodrich's own student days and to the early years of the founder of Liberty Fund.

The Reading Room

Essays of Elia: From the Liberty Fund Rare Book Room

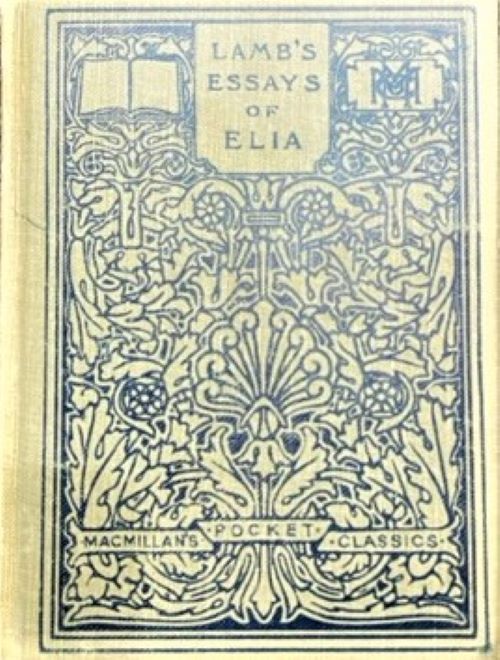

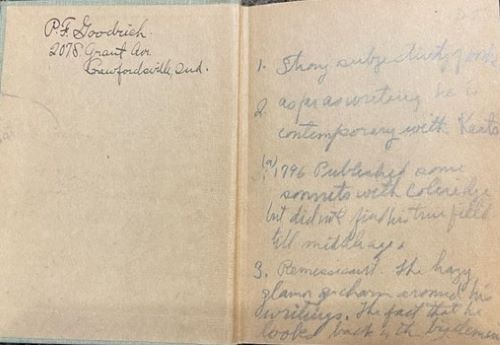

Goodrich's copy is a small pocket edition from Macmillan, with a date of 1913. It's clothbound in gray, with an ornate blue William Morris style cover design. Measuring just 4x6", it's an ideal size to slip into a pocket on the way to class.

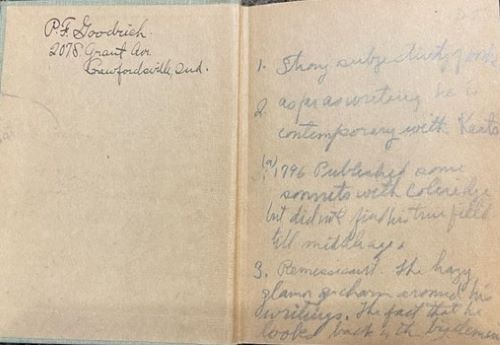

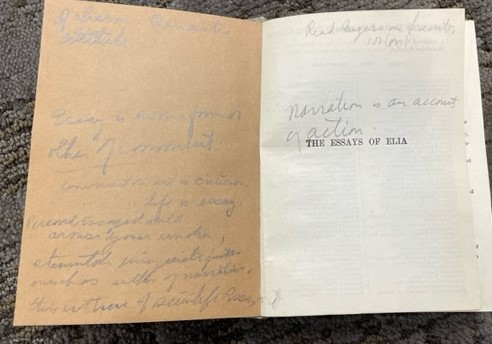

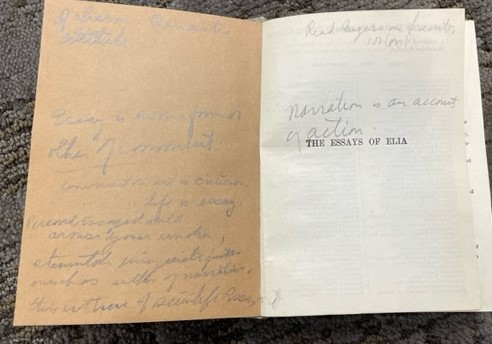

And Goodrich clearly brought it with him. The book is profusely annotated, especially in the introductory material. (This is particularly interesting for those who know that in later years, Goodrich objected strenuously to the interpretive lens provided by introductions and was said to excise them from books before giving them to people.) Goodrich has also clearly used the blank pages at the front of the book to take class notes, to remind himself of the assignments that are coming up, and to record the prompt for an assigned essay of his own.

I find this charming because it's precisely how I've treated my own books since I was an undergraduate. I always felt guilty about it, but now it seems like a potentially useful record of my past reading. Certainly, for those interested in Goodrich, his annotations provide a view into his education and the life of his mind.

It's worth recommended Essays of Elia as a text on its own, independent of any connection to Goodrich. Little read these days, it was once a standard text in college literature classes, and it contains witty, charming, and thoughtful meditations on any number of subjects. While aspects of Lamb's work, particularly some of the humor directed at non-English cultures, has not held up well over the years, much of the rest of his humor has. I was introduced to Lamb's essay "A Dissertation Upon Roast Pig" as a kid. Its pillorying of an overly strict adherence to tradition through the story of people who accidentally invent roast pork when a house burns down, and then proceed to build flimsier and flimsier houses in order to burn them down and produce more roast pork has remained with me ever since.

And Goodrich clearly brought it with him. The book is profusely annotated, especially in the introductory material. (This is particularly interesting for those who know that in later years, Goodrich objected strenuously to the interpretive lens provided by introductions and was said to excise them from books before giving them to people.) Goodrich has also clearly used the blank pages at the front of the book to take class notes, to remind himself of the assignments that are coming up, and to record the prompt for an assigned essay of his own.

I find this charming because it's precisely how I've treated my own books since I was an undergraduate. I always felt guilty about it, but now it seems like a potentially useful record of my past reading. Certainly, for those interested in Goodrich, his annotations provide a view into his education and the life of his mind.

It's worth recommended Essays of Elia as a text on its own, independent of any connection to Goodrich. Little read these days, it was once a standard text in college literature classes, and it contains witty, charming, and thoughtful meditations on any number of subjects. While aspects of Lamb's work, particularly some of the humor directed at non-English cultures, has not held up well over the years, much of the rest of his humor has. I was introduced to Lamb's essay "A Dissertation Upon Roast Pig" as a kid. Its pillorying of an overly strict adherence to tradition through the story of people who accidentally invent roast pork when a house burns down, and then proceed to build flimsier and flimsier houses in order to burn them down and produce more roast pork has remained with me ever since.