Encyclopedic Liberty and Industry

This illustrated essay explores some images of "liberty" and "industry" from Diderot’s Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (Encyclopaedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts) (1751-1772). They have been taken from Liberty Fund’s anthology of articles, Encyclopedic Liberty: Political Articles in the Dictionary of Diderot and D'Alembert (2016) and the supplementary volumes of illustrations from the original 18th century edition.

|

The Encyclopédie will write the history of our century's wealth in this subject; it will do so for our own century, which is ignorant of this history, and for the centuries to come, which thus will be able to go further. Discoveries in the arts will no longer run the danger of being forgotten; facts will become known to the philosophers, and reflection will be able to simplify and enlighten blind practice. |

| [Illustration on the title page of Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (1751), volume 1.] | Editors' Introduction to vol. 3 (1753) |

Introduction

This illustrated essay explores some images of "liberty" and "industry" from Diderot's Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (Encyclopaedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts) (1751-1772). They have been taken from Liberty Fund's anthology of articles, Encyclopedic Liberty: Political Articles in the Dictionary of Diderot and D'Alembert (2016) and the supplementary volumes of illustrations from the original 18th century edition. The Liberty Fund anthology contains 82 articles about politics as well as economics (the alphabetical Table of Contents). The articles on economics (in alphabetical order) are:

- Quesnay, Cereals (Grains) with Maxims of Economic Government [Volume 7 (1757)]

- Véron de Forbonnais, Competition (Concurrence) [Volume 3 (1753)]

- Damilaville, Five Percent Tax (Vingtième) [Volume 17 (1765)]

- Turgot, Foundation (Fondation) [Volume 7 (1757)]

- Jaucourt, Industry (Industrie) [Volume 8 (1765)]

- Jaucourt, Invention [Volume 8 (1765)]

- Diderot, Masterpiece (Chef-d'Œuvre) [Volume 3 (1753)]

- Faiguet de Villeneuve, Masterships (Maîtrises) [Volume 9 (1765)]

- Deleyre, Pin (Epingle) [Volume 5 (1755)]

- Diderot, Political Arithmetic (Arithmétique Politique) [Volume 1 (1751)]

- Boulanger, Political Economy (Œconomie Politique) [Volume 11 (1765)]

- Diderot, Poorhouse (Hôpital) [Volume 8 (1765)]

- Damilaville, Population [Volume 13 (1765)]

- Anon., Property (Propriété) [Volume 13 (1765)]

- Faiguet, Savings (Epargne) [Volume 5 (1755)]

- Jaucourt, Slavery (Esclavage) [Volume 5 (1755)]

- Jaucourt, Tax (Impôt) [Volume 8 (1765)]

- Jaucourt, Trade (Négoce) [Volume 11 (1765)]

- Véron de Forbonnais, Trading Company (Compagnie de Commerce) [Volume 3 (1753)]

- Jaucourt, Traffic in Blacks (Traite des Nègres) [Volume 16 (1765)]

In Encyclopedic Liberty there are five illustrations which accompany the text which we will discuss first. They are:

- Libertas (Liberty)

- Industria (Industry)

- Res Domestica (Frugality)

- Ars Politica (Statecraft)

- Amor Patriae (Patriotism)

This section is followed by a selection of illustrations from the original edition which cover a number of economic activities and a couple of other interesting and amusing topics (in bold):

|

|

I have selected a couple of dozen images from the supplementary volumes to the Encyclopédie which contained hundreds of illustrations of industrial processes (some new, some traditional) and everyday occupations of skilled workers. The selection criteria were to show as many different occupations as possible to show the range of interests of the Encyclopedists, to find images that also contained people in order to show the social nature of economic activity, to include some classic depictions of work which economists like Adam Smith and J.B. Say would use to illustrate the possibilities opened up by the division of labour (Smith's pin making factory, J.B. Say's example of playing cards), and to show images where some political message was sometimes inserted. Many of these images are accompanied by relevant quotations from the articles.

Sources

Denis Diderot, Encyclopedic Liberty: Political Articles in the Dictionary of Diderot and D'Alembert. By Denis Diderot and Jean Le Rond d'Alembert. Edited and with an Introduction by Henry C. Clark. Translated by Henry C. Clark and Christine Dunn Henderson (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2016). </titles/2732>.

Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, par une société de gens de lettres. Mis en ordre & publié par M. Diderot,... ; & quant à la Partie Mathématique, par M. D'Alembert,... Tome premier [A-AZ]. (A Paris : chez Briasson : David l'aîné : Le Breton : Durand, 1751). Online at Gallica <http://mazarinum.bibliotheque-mazarine.fr/records/item/2111-redirection>.

The ARTFL Encyclopédie <https://encyclopedie.uchicago.edu/> and The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Translated by Malcolm Eden. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2008. <https://quod.lib.umich.edu/d/did/>.

Illustrations in the text Encyclopedic Liberty are reproduced from Cesare Ripa, Baroque and Rococo Pictorial Imagery: The 1758–60 Hertel Edition of Ripa's "Iconologia" with 200 Engraved Illustrations, ed. Edward A. Maser (New York: Dover Publications, 1971), Amor Patriae (Patriotism), 26; Libertas (Liberty), 62; Industria (Industry), 147; Res Domestica (Frugality), 148; Ars Politica (Statecraft), 199.

Related Material

See also the following illustrated essay on related topics:

- "New Playing Cards for the French Republic (1793-94)" </pages/new-playing-cards-for-the-french-republic-1793-94>.

- "Adam Smith and J.B. Say on the Division of Labour" </pages/adam-smith-and-j-b-say-on-the-division-of-labour>.

I. Illustrations in Clark's book Encyclopedic Liberty:

Libertas (Liberty)

Source:Encyclopedic Liberty, p. 580 </titles/2732#Diderot_1642_2093>. [See a larger version of this image.]

"In the foreground sits a female figure for liberty, with various symbols of liberty, victory, and peace. In the background the story of William Tell is depicted."

The image accompanies the article by Jaucourt, Switzerland (Suisse), Volume 15 (1765), pp. 579-87. Sometimes the authors would sneak in political commentary into seemingly inoccuous articles on geography, for example. Here Jaucourt discusses constitutional government, struggles for liberty, and tyrannicide using the historical example of Switzerland and the story of William Tell.

All the historians inform us that this conspiracy acquired irresistible force by an unforeseen event. Grisler, the governor of Uri, got the idea of inflicting a kind of barbarism that was at once horrible and ridiculous. He had a pole planted with his hat on it in the marketplace of Altorff, capital of the canton of Uri, and ordered everyone on pain of death to salute this hat while removing their own and to genuflect with the same respect as if the governor were there in person.

One of the conspirators, an intrepid man named William Tell who was incapable of servility, did not salute the hat. Grisler sentenced him to be hanged, and by means of a tyrannical nicety, he gave him his pardon, but only on condition that this father, who was known as a very skilled archer, hit an apple placed on his son's head with one arrow. The father fired and was lucky enough or skillful enough to hit the apple without touching his son's head. The whole populace exploded with joy and clapped their hands in general acclamation. Noticing a second arrow under Tell's clothes, Grisler asked him the reason for it and promised to pardon him, whatever intention he might have had. "It was designed for you," Tell responded, "if I had wounded my son."

Nonetheless, frightened by the risk he had run of killing his dear son, Tell waited for the governor at a place where he was to pass several days later. Spotting him, Tell aimed at him, shot him in the heart with that same arrow, and left him dead right there. He informed his friends of his exploit on the spot and kept himself in hiding until the day of their plan's implementation. [p. 583 </titles/2732#Diderot_1642_2102>]

See also the other articles explicitly about liberty:

- Anon., Natural Liberty (Liberté Naturelle) [Volume 9 (1765)], pp. 329-30

- Anon., Civil Liberty (Liberté Civile) [Volume 9 (1765)], pp. 331-32

- Jaucourt, Political Liberty (Liberté Politique) [Volume 9 (1765)], pp. 333-34

- Jaucourt, Liberty; Inscription, Medals (Liberté) [Volume 9 (1765)], pp. 335-36

- Jaucourt, Liberty; Mythology, Iconology (Liberté) [Volume 9 (1765)], pp. 337-38

As well as the important article by Diderot, Political Authority (Autorité Politique) [Volume 1 (1751)], pp. 12-20. The opening paragraphs of which state:

Political Authority. No man has received from nature the right to command others. Liberty is a gift from heaven, and each individual of the same species has the right to enjoy it as soon as he enjoys the use of reason. If nature has established any authority, it is paternal control; but paternal control has its limits, and in the state of nature, it would terminate when the children could take care of themselves. Any other authority comes from another origin than nature. If one seriously considers this matter, one will always go back to one of these two sources: either the force and violence of an individual who has seized it, or the consent of those who have submitted to it by a contract made or assumed between them and the individual on whom they have bestowed authority.

Power that is acquired by violence is only usurpation and only lasts as long as the force of the individual who commands can prevail over the force of those who obey; in such a way that if the latter become in their turn the strongest party and then shake off the yoke, they do it with as much right and justice as the other who had imposed it upon them. The same law that made authority can then destroy it; for this is the law of might. Sometimes authority that is established by violence changes its nature; this occurs when it continues and is maintained with the express consent of those who have been brought into subjection, but in this case it reverts to the second case about which I am going to speak; and the individual who had arrogated it then becomes a prince, ceasing to be a tyrant.

Power that comes from the consent of the people necessarily presupposes certain conditions that make its use legitimate, useful to society, advantageous to the republic, and that set and restrict it between limits: for man must not and cannot give himself entirely and without reserve to another man, because he has a master superior to everything, to whom he alone belongs in his entire being. It is God, whose power always has a direct bearing on each creature, a master as jealous as absolute, who never loses [14] his rights and does not transfer them.3 He permits for the common good and for the maintenance of society that men establish among themselves an order of subordination, that they obey one of them, but he wishes that it be done with reason and proportion and not by blindness and without reservation, so that the creature does not arrogate the rights of the creator. Any other submission is the veritable crime of idolatry. To bend one's knee before a man or an image is merely an external ceremony about which the true God, who demands the heart and the mind, hardly cares and which he leaves to the institution of men to do with as they please the tokens of civil and political devotion or of religious worship. Thus it is not these ceremonies in themselves, but the spirit of their establishment that makes their observance innocent or criminal. An Englishman has no scruples about serving the king on one knee; the ceremonial only signifies what people wanted it to signify. But to deliver one's heart, spirit, and conduct without any reservation to the will and caprice of a mere creature, making him the unique and final reason for one's actions, is assuredly a crime of divine lèse-majesté of the highest degree. Otherwise this power of God about which one speaks so much would only be empty noise that human politics would use out of pure fantasy and which the spirit of irreligion could play with in its turn; so that all ideas concerning power and subordination coming to the point of merging, the prince would trifle with God, and the subject with the prince. [p. 13 </titles/2732#Diderot_1642_328>]

Industria (Industry)

Source: Encyclopedic Liberty, p. 290 </titles/2732#Diderot_1642_1254>. [See a larger version of this image.]

"In foreground, woman with spur, hourglass, rooster, and beehive (all symbols of industriousness); in background, the Roman freedman C. Furius Chresimus rebuffs witchcraft charges by showing proof of his own industrious farming."

The image accompanies the article by Jaucourt, Industry (Industrie) [Volume 8 (1765)] which discusses, among other things, the extraordinary impact new technologies and machines were having on many sectors of production. Many of the illustrations in the supplementary volumes (several are included below) focus on the new techniques and machines which were transforming "industry." One of the arguments Jaucourt makes is that the introduction of new machines and industrial processes was hampered by government regulation and taxation as this passage shows:

It is a timeworn truth almost shameful to repeat, but in certain countries, there are people who evade the ways and means offered them to make the land fruitful, and who persist in sacrificing principles of this kind to the prejudices that dominate them. They are unaware that the obstacles imposed on industry completely destroy it, and that on the other hand, the efforts of industry that are encouraged make it prosper marvelously through the emulation and profit that result. Far from imposing taxes on industry, one must give incentives to those who have best cultivated their fields, and to the workers who have gone furthest in making their work meritorious. No one is unaware of how far this method has succeeded in the three realms of Great Britain. In our day, by this means alone, one of Europe's most significant cloth manufactures has been set up in Ireland. [p. 291, </titles/2732#Diderot_1642_1257>]

He also addresses the problem of vested interests (like the Thames ferrymen) who lobby the government to prevent competition and lower prices made possible by technical innovation (the construction of Westminster Bridge). Instead, he argues, France had to industrialise first and to do this it had to deregulate its economy:

Such objections are typically devoid of good sense and enlightenment. They resemble the objections that the Thames boatmen put forward against the construction of the Westminster bridge. Haven't those boatmen found something to do with themselves, while the construction of that bridge has been expanding new commodities throughout the city of London? Isn't it better to anticipate the industry of other peoples in using machines, than to wait for them to force us to adopt the use of those machines in order to preserve our competitive position in the same markets? The surest profit will always go to the nation that has been industrious first; and all things equal, the nation whose industry is the freest will be the most industrious. [p. 292, </titles/2732#Diderot_1642_1261>.]

Res Domestica (Frugality)

Source: Encyclopedic Liberty, p. 146 </titles/2732#Diderot_1642_732>. [See a larger version of this image.]

"A woman with compasses (for measuring resources) in her right hand and a wand and ship's rudder (for household leadership) in her left (alongside beehive). In the background, a rich dissolute household is depicted on the left, a modest and frugal household on the right."

The image accompanies the article by Faiguet, Savings (Epargne) [Volume 5 (1755)] which discusses both individual saving or "economising" as well as how the state and the state church might save the taxpayers from profligate spending. An example of the former:

Nonetheless, by a lack of justice that is only too ordinary, the sober, attentive, and hardworking man who, by his work and savings, lifts himself imperceptibly above his fellows is commonly labeled a miser; but would to heaven that we had more misers of that kind. Society would find itself much better off that way, and we would not suffer as many injustices on men's part. In general these men—repressed, if you will, but more economizers than misers—are almost always good company; sometimes, they even become compassionate. And if they are not found to be generous, they are at least found to be quite fair-minded. Finally, one almost never loses anything with them, whereas one loses more often than not with the spendthrifts. These economizers, in a word, function within the framework of honest saving, on which we wrongly lavish the word avarice. [p. 149, </titles/2732#Diderot_1642_742>.]

An example of the latter:

In following the same taste for saving, how many cutbacks, how many useful and practicable establishments of so many different kinds! What savings are possible in the dispensing of justice, in administration and in finance, since it would be easy, by simplifying the collection of taxes and other matters, to employ many fewer people in all those things than at present! This item is important enough to merit specific treatises; we have many on this subject that one may very fruitfully read.

What savings are possible in the discipline of our troops, and what advantages could be drawn from it for king and state, if we devoted ourselves as the ancients did to occupying them usefully! I will talk about it on some other occasion.

What savings are possible in the administration of the arts and commerce, by lifting the obstacles found at every turn to the transport and sale of merchandise and commodities—but especially by restoring little by little the general liberty of the crafts and trades, such as it existed in the past in France, and such as it still exists today in many neighboring states; for that reason abolishing the onerous formalities of masterships, initiations, [154] notarized letters of apprenticeship, and other such practices that stop the activity of workers, often alienating them completely from useful occupations and then consigning them to miserable extremities; practices, finally, that the spirit of monopoly introduced into Europe and that are only maintained in these enlightened times by the inattentiveness of legislators. All of us have only too much aversion to arduous work; we must not increase its difficulty, nor generate occasions or pretexts for our laziness. [pp. 153-54, </titles/2732#Diderot_1642_768>]

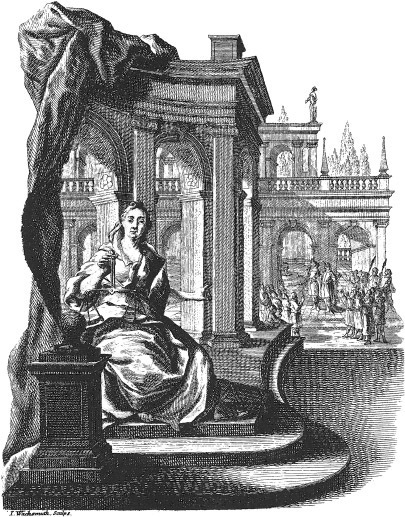

Ars Politica (Statecraft)

Source:Encyclopedic Liberty, p. 306 </titles/2732#Diderot_1642_1308> . [See a larger version of this image.]

"Female symbol of statecraft in foreground, with scales (for justice and prudence) in her right hand and lictors' rods (for enforcement) at her feet; in background, Spartan citizens swear oath to Lycurgus to follow laws that he, as the foundational lawgiver of the community, had laid down."

The image accompanies the article by Saint-Lambert, Legislator (Législateur) [Volume 9 (1765)], pp. 307-27. As the editor noted about this article, "Long thought to be the work of Diderot, the present article is now known to have been written by the Marquis de Saint-Lambert. Either way, the essay is widely agreed to be one of the most important and richly textured political articles in the Encyclopédie. The author's wide-ranging approach to government, with its emphasis on climate, religion, manners, and liberty, evokes Montesquieu and Hume. His distinction between the esprit de communauté and the esprit de propriété is an original formulation, as is his precise way of drawing a relationship between commerce and constitutions, with its particular emphasis upon Europe's constitutional diversity." Among many interesting passages this one discusses the influence commerce has and the need for the Legislator to avoid wars which disrupt trade:

All men from all countries have become necessary for the exchange of the fruits of industry and the products of their earth; commerce is a new bond for men; it is in the interest of every nation that another nation conserves its wealth, industry, banks, luxury, and agriculture; the ruin of Leipzig, Lisbon, and Lima caused bankruptcy to spread throughout Europe and had an effect on the fortunes of millions of citizens.

Commerce, as enlightenment, diminishes the ferocious part of man, but just as enlightenment removes the enthusiasm of narrow esteem, commerce also removes perhaps the enthusiasm for virtue; it slowly extinguishes the spirit of disinterestedness, which is replaced with that of justice; it softens the customs and morals that are refined by enlightenment, but by directing men to what is useful more than to what is beautiful, to the prudent rather than to the grand, it diminishes perhaps the generosity, power, and greatness of morality.

Given the commercial outlook and the knowledge that men today have of the true interests of all nations, it follows that legislators must be less preoccupied with defense and conquest than they previously were; it follows that they must favor the cultivation of the land and the arts and encourage the consumption and the manufacture of their products; but they must take care at the same time that refined customs and morals do not lose their force and that the high regard of martial virtues are maintained. [p. 326 </titles/2732#Diderot_1642_1379>]

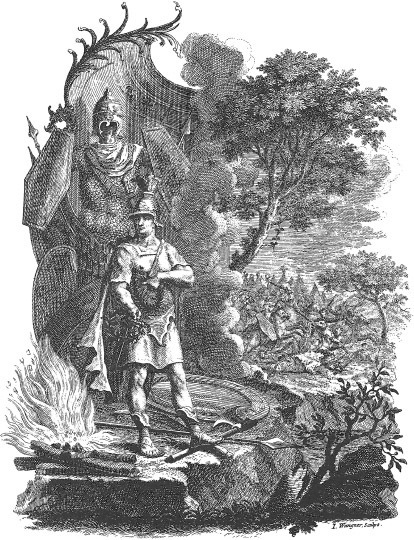

Amor Patriae (Patriotism)

Source: Encyclopedic Liberty, p. 472 </titles/2732#Diderot_1642_1797>. [See a larger version of this image.]

"In foreground, a patriot with trophy, brazier, wreaths, weapons, and other symbols of civic spirit and patriotic achievement; in background, the Roman dictator Camillus, who broke his oath to the Gauls to save Rome."

The image accompanies the article by Jaucourt, Patriot (Patriote) [Volume 12 (1765)], pp. 473-76. Some of his ideas and examples of patriots were taken from Joseph Addison's 1713 play Cato (online here) concerning the opposition by true patriots to tyrants like Julius Caesar:

Serving one's Country is not a chimerical duty but a real obligation. Any man who agrees that there are duties derived from nature's constitution and from the moral good and evil of things will recognize the duty that obliges us to do good for our Country, or else he will be reduced to the most absurd inconsistency. Once he has acknowledged this duty, it is not difficult to prove to him that this duty is proportioned to the means and occasions that he has to fulfill it, and that nothing can exempt us from what we owe to Country as far as it needs us and as far as we can serve it.

Ambitious slaves will say that it is very hard to renounce the pleasures of society in order to dedicate one's days to the service of one's Country. Base souls, you have no idea then of noble and solid pleasures! Believe me, there are truer and more delicious ones in a life occupied with procuring the good of one's Country than Caesar ever knew in destroying the liberty of his own; or Descartes in building new worlds; or Burnet in creating a world before the flood. In discovering the true laws of nature, Newton himself knew no greater intellectual pleasure than is tasted by a true patriot who extends all the force of his understanding and who guides all his thoughts and actions toward the good of his Country. [p. 474 </titles/2732#Diderot_1642_1802>]

II. Images from the Encyclopédie

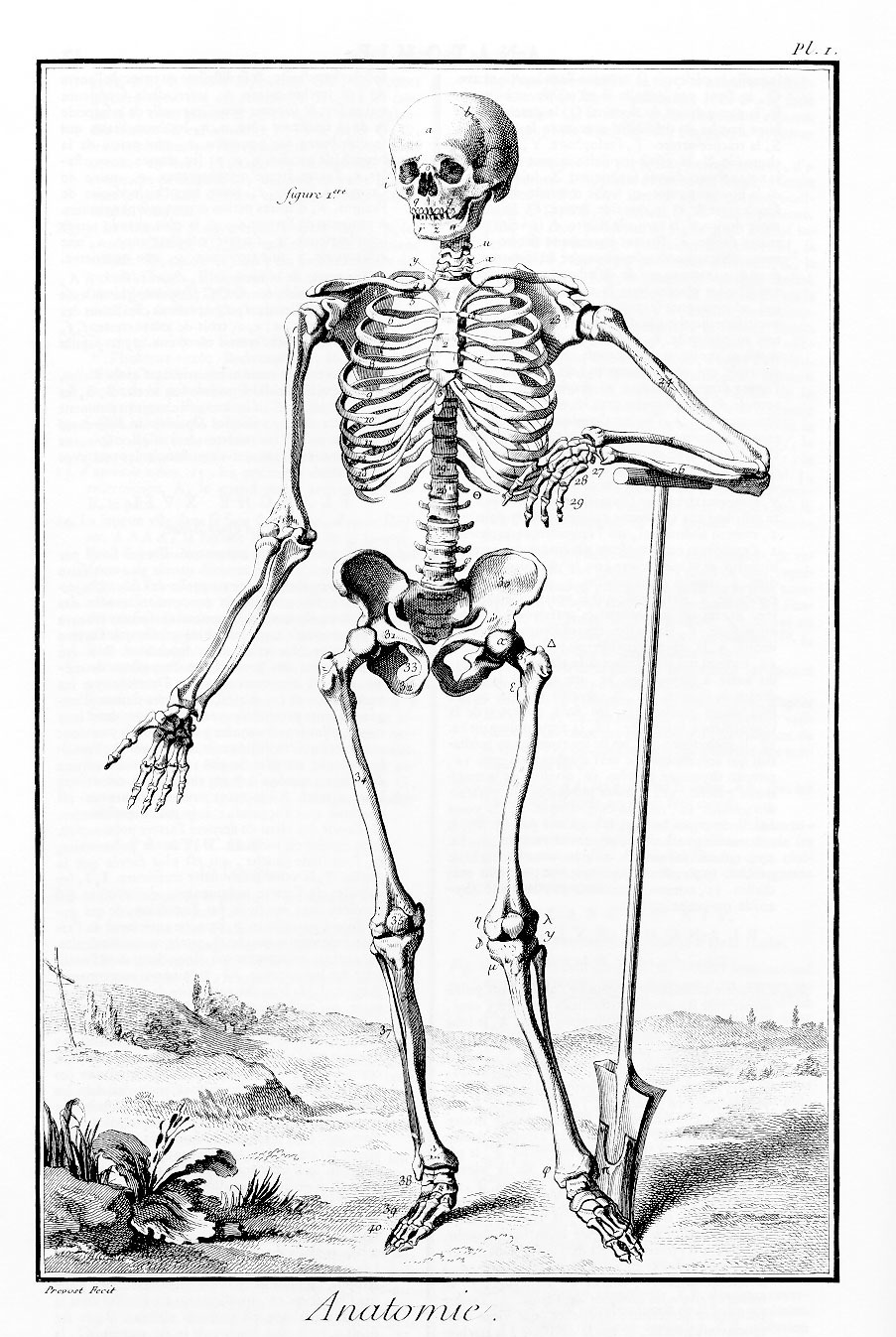

- Anatomy

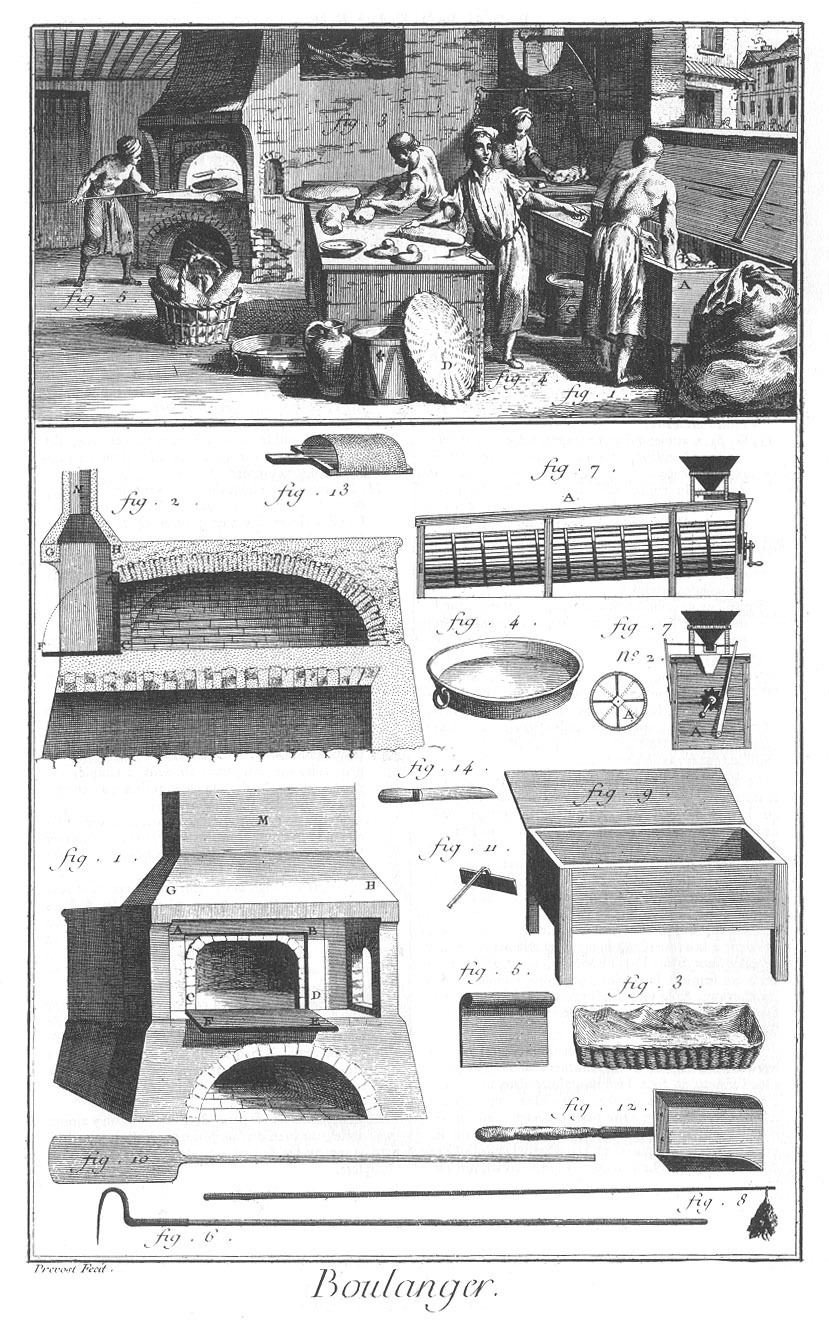

- Baking Bread

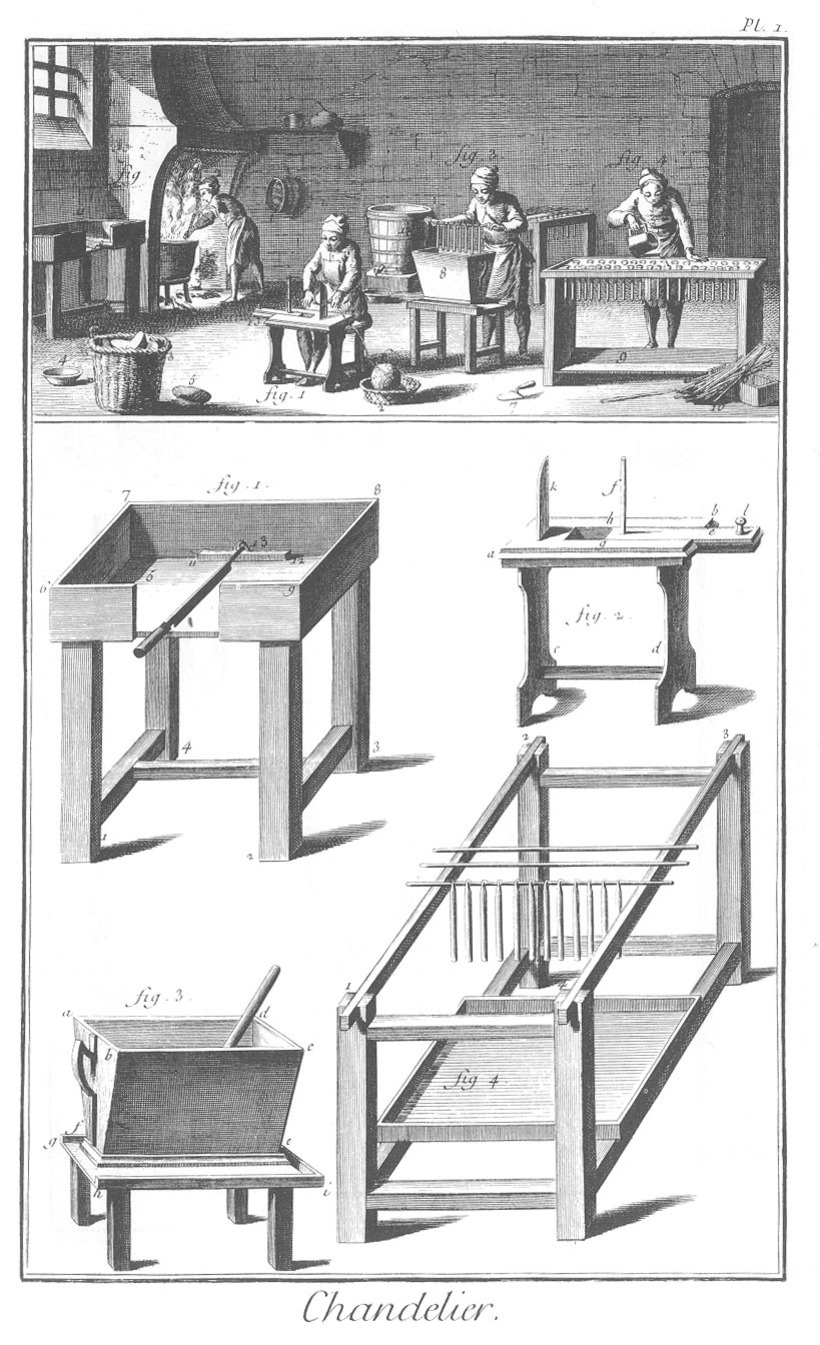

- Candle making

- Charcoal

- Clock making

- Coin minting

- Cotton growing and spinning

- Cutler

- Iron forge

- Lace making

- Nail making

- Pin making

- Playing Cards

- Plowing

- Printing

- Shoe making

- Sugar plantation

- Sword making and Armor

- Wheelwright

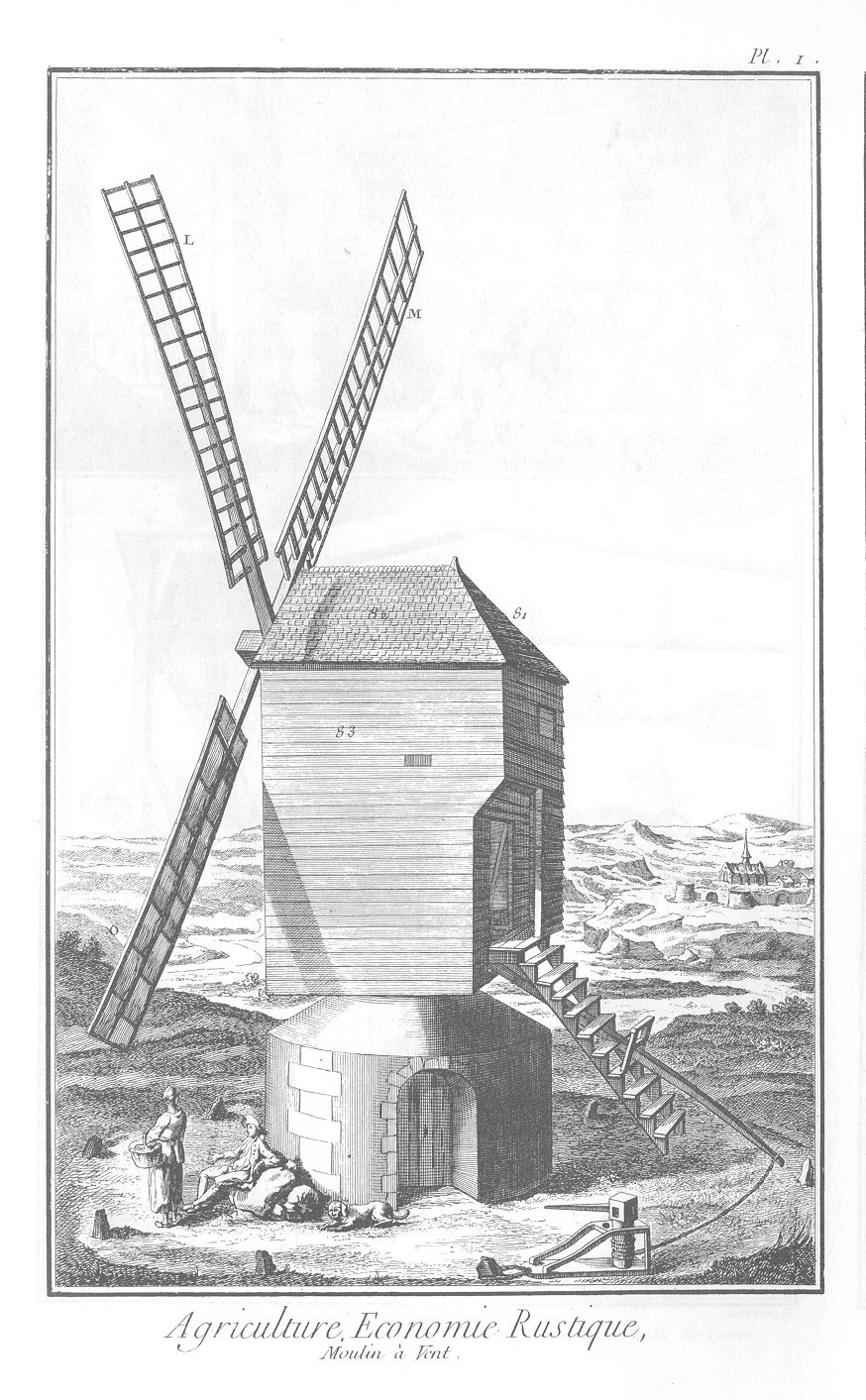

- Windmill

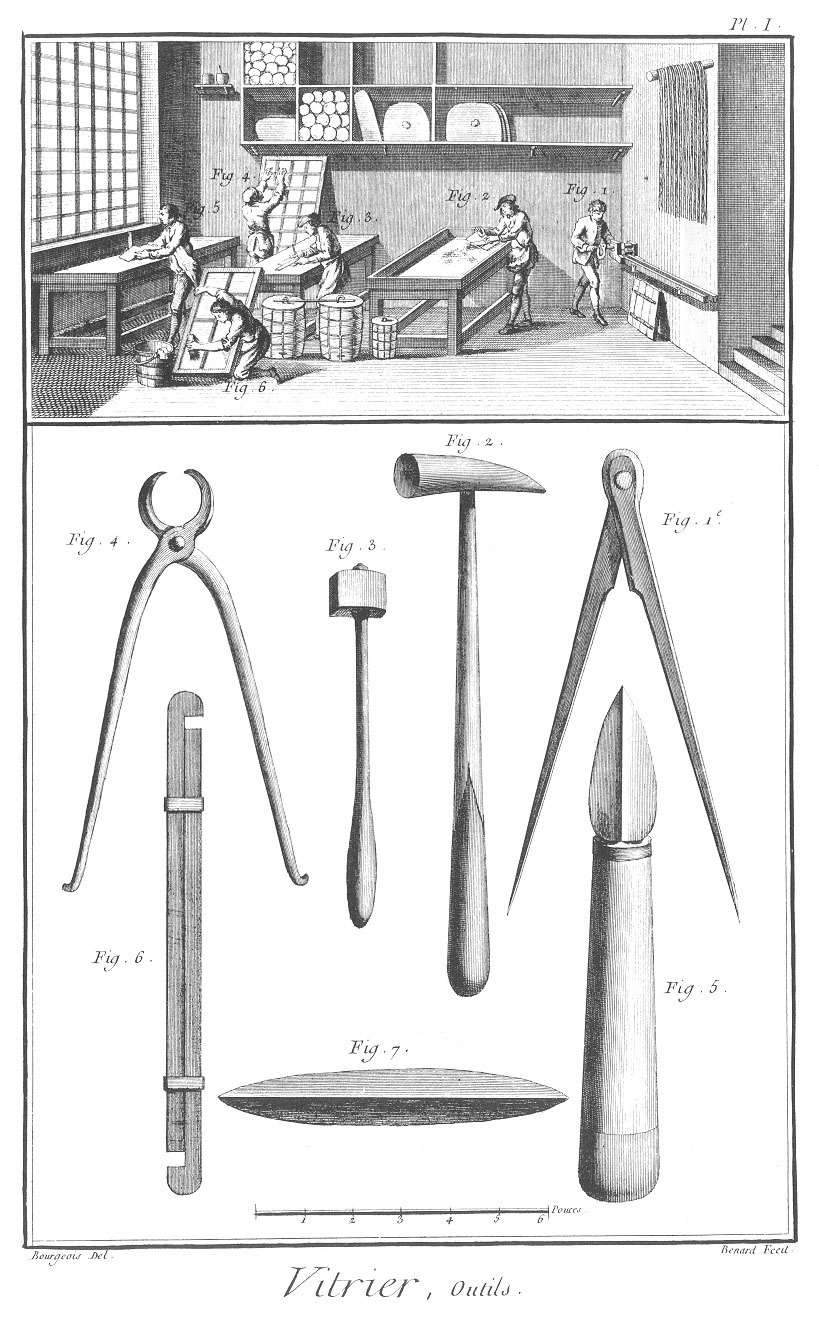

- Window making

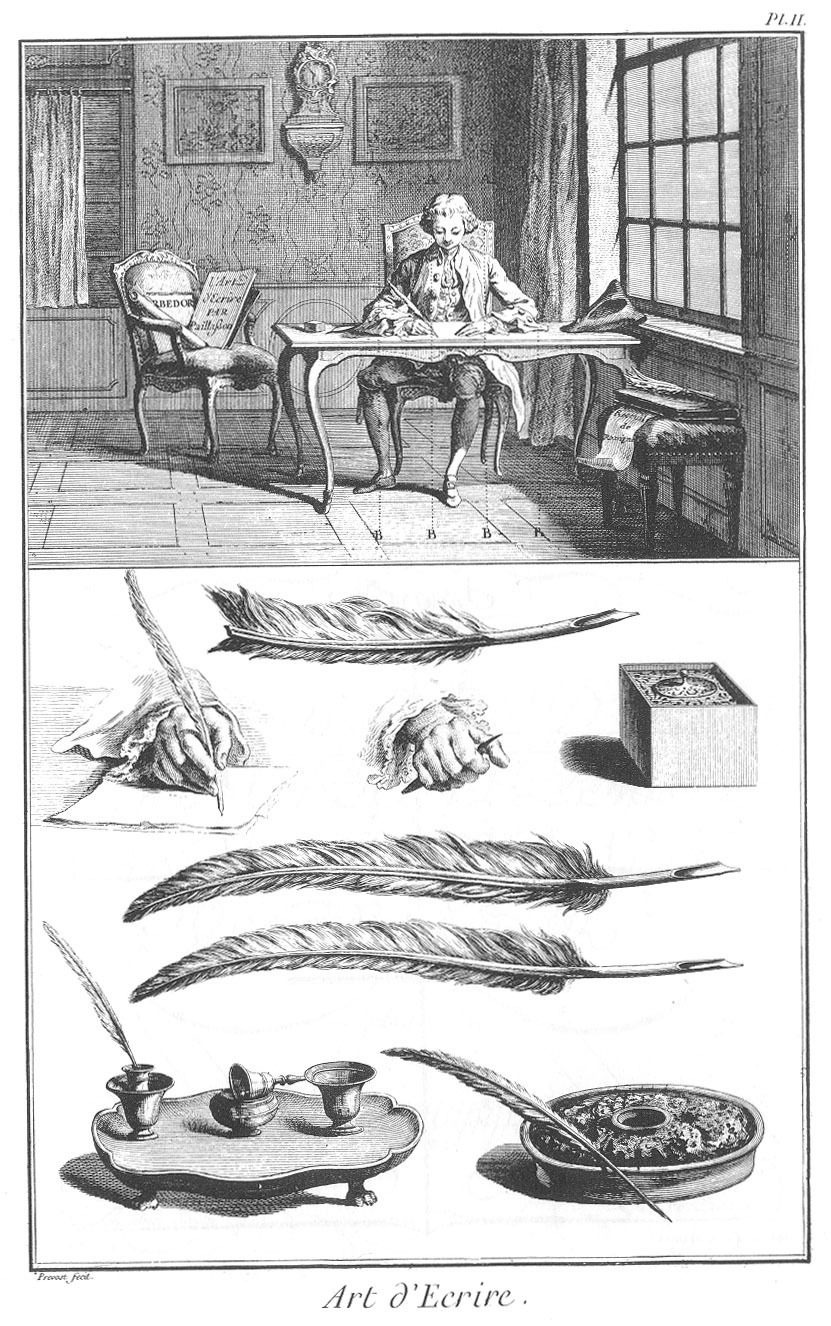

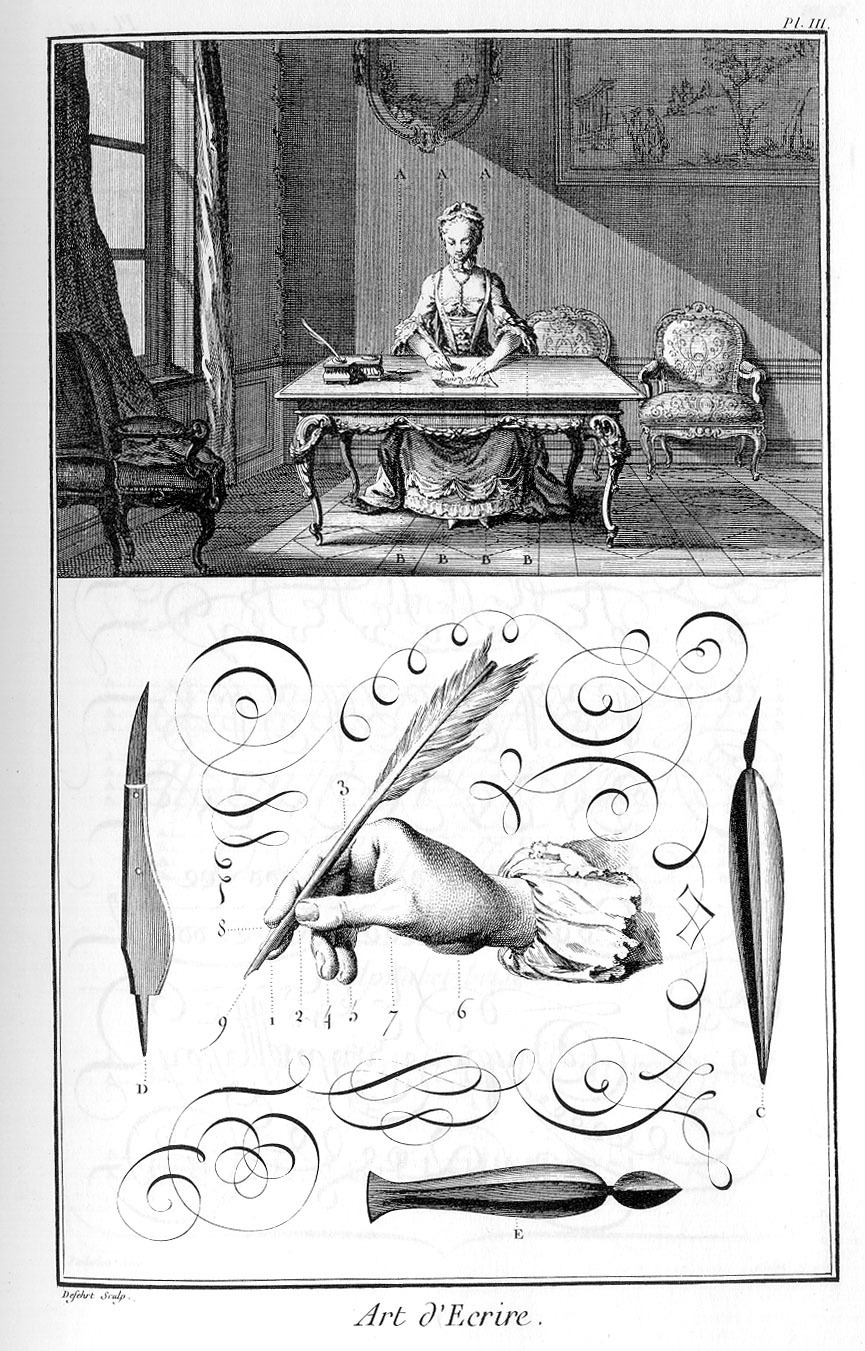

- The Art of Writing

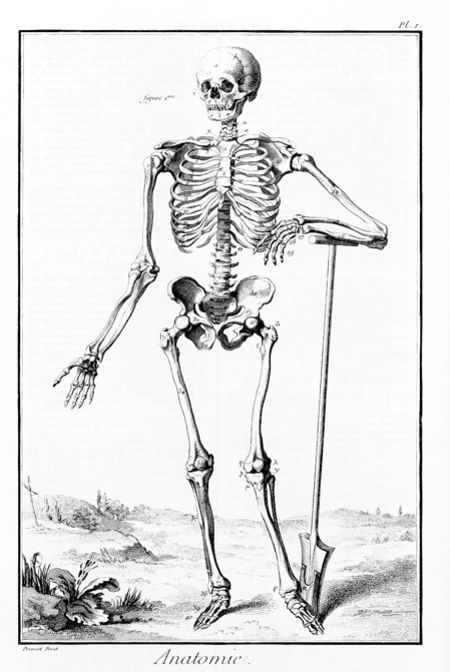

Human Anatomy

Plate I: Anatomy

Source: "Anatomy." The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2010. Web. <http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0001.359>. Trans. of "Anatomie," Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 1 (plates). Paris, 1762.

Note: Let us begin with an amusing example. The Encyclopedists managed to politicise everything, including their study of human anatomy. The poses adopted by the skeletons reveal this clearly. Here we have an "industrious" skeleton leaning against a shovel. To its left we can see a cross and possibly the grave he has just dug for him or herself, or perhaps dug themself out of? The suggestion is that man is mortal but knowledge will live forever.

Quote from Encyclopedic Liberty:

There are only two true sources of wealth: man and the land. Man is worth nothing without the land, and land yields nothing without man. The true worth of man lies in numbers; the more numerous a society is, the more powerful it will be in times of peace and the more formidable in times of war. This is why a sovereign should give serious attention to increasing the number of his subjects. The greater their number, the more merchants, workers, and soldiers he will have. …

It is not sufficient, however, for a state to have many men; they must be industrious and healthy. Men will be healthy if their standards of morality are high and if they can easily become and remain affluent. Men will be industrious if they are free. The lack of commercial freedom can result, in a given province, in affluence that can become an evil as terrible as poverty. In such a case the nation is being subjected to the worst possible government. Our children will be our men; a country, therefore, must take care of its children. …

We could add a great many more items to these clear and simple principles. A sovereign could find them himself if he had the courage and good will needed to put them into practice. [Article by Diderot, "Man," vol.8 (1765 ).]

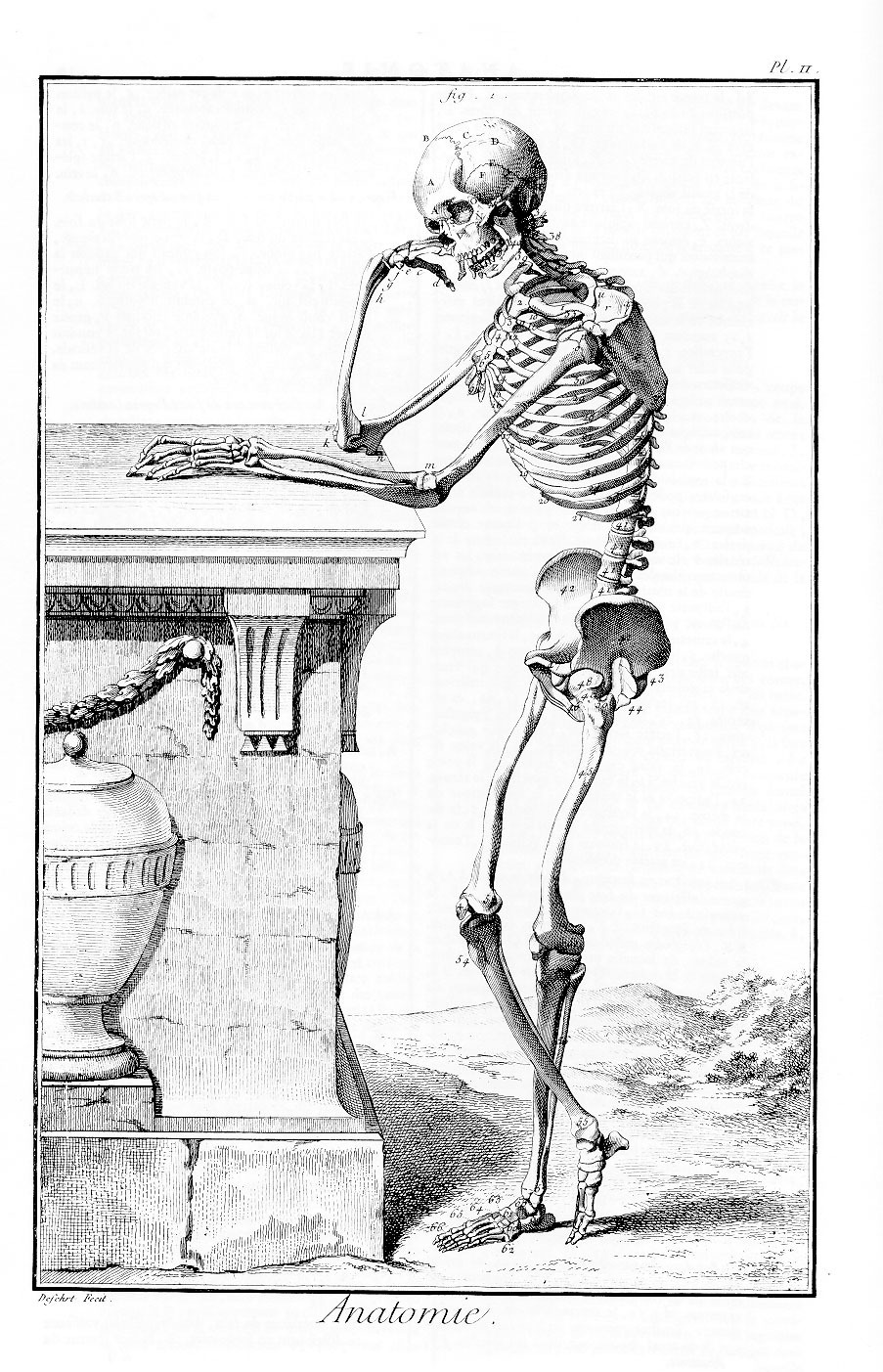

Plate II: Anatomy

Note: Here we have a thoughtful, philosophical skeleton, leaning against a tomb (perhaps his or her own?) contemplating the meaning of life or perhaps the folly of undertaking a project as large, as difficult, and as fraught with danger as the Encyclopédie. It reminds me of Rodin's statue of "Le Penseur" (The Thinker) (1880) who is sitting rather than standing.

Quote from Encyclopedic Liberty:

Natural Rights. These words are used so frequently that almost everyone is convinced that they are clearly understood. This feeling is common to the philosopher and to the man who does not think, with the only difference that in regard to the question "What are rights?" the latter, in that moment lacking both terms and ideas, refers you to the tribunal of conscience and remains silent, while the first is only reduced to silence and to more profound reflections after having turned in a vicious circle that brings him back to the very point from which he departed or draws him to some other question that is not less difficult to resolve than the one he thought he was rid of by its definition.

The philosopher under question says: "Rights are the foundation or the primary object of justice." But what is justice? "It is the obligation to render to each person what belongs to him." But what belongs to one rather than to another in a state of things where everything belongs to everyone and where perhaps the distinct idea of obligation would not yet exist? And what would an individual owe to others if he were to allow them everything and ask nothing of them? It is here that the philosopher begins to feel that of all the notions of morality, that of natural rights is one of the most important and most difficult to determine. Therefore we believe we will have accomplished a great deal in this article if we have succeeded in clearly establishing a few principles that might assist someone to resolve the most considerable difficulties customarily proposed against the notion of natural rights. For this purpose it is necessary to discuss the question thoroughly and to advance nothing that is not clear and evident, with at least the kind of evidence that moral questions permit and that satisfy every sensible man. [Diderot, "Natural Right," vol. 5 (1755).]

Baking Bread

Source: Diderot, Denis. "Baker." The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Translated by Malcolm Eden. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2008. Web. <http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0000.845>. Trans. of "Boulanger," Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 2. Paris, 1752.

Note: The top panel shows the interior of a bakers's shop where workers are making the dough and putting it in the oven to bake. The number of bakers in Paris was strictly limited by the government and the supply of grain was heavily regulated in order to prevent shortages and high prices in time of scarcity (this of course was impossible to do). The Encyclopedistes were early supporters of a policy of free trade, especially in grain, within France.

Quote from Encyclopedic Liberty:

This competition is either external or internal. ... This external competition is not obtained by force; it is the value of the efforts that human industry makes to grasp the tastes of the consumer, even to predict them and stimulate them. ...

The other type of internal competition is that of work among subjects: it consists in the fact that each of them has the capacity to be employed in the manner that he believes most lucrative, or that is most agreeable to him.

This is the principal basis of the freedom of trade: it alone contributes more than any other means to bringing to a nation that external competition which enriches it and makes it powerful. The reason is very simple. I won't, perhaps, say that every man is so unfortunate as to be naturally inclined to work, but he is naturally inclined to procure his ease; and this ease, the wages of his labor, then makes his occupation agreeable to him. Thus, as long as no internal vice in the state's administration sets obstacles to human industry, this industry enters by itself into the lists. The more substantial the number of its products, the more moderate is their price; and this price moderation obtains the preference of foreigners. ...

Such are the prodigious effects of this principle of competition—so simple at first sight, as are virtually all the principles of commerce. This one in particular seems to me to have a very rare advantage, namely to be subject to no exceptions. [Article on "Competititon," vol. 3 (1753).]

Candlemaker

Plate I: Candle Maker

Source: "Candlemaker." The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2010. Web. <http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0001.411>. Trans. of "Chandelier," Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 2 (plates). Paris, 1763.

Note: The workshop of a candle maker. Note that there are only women workers here.

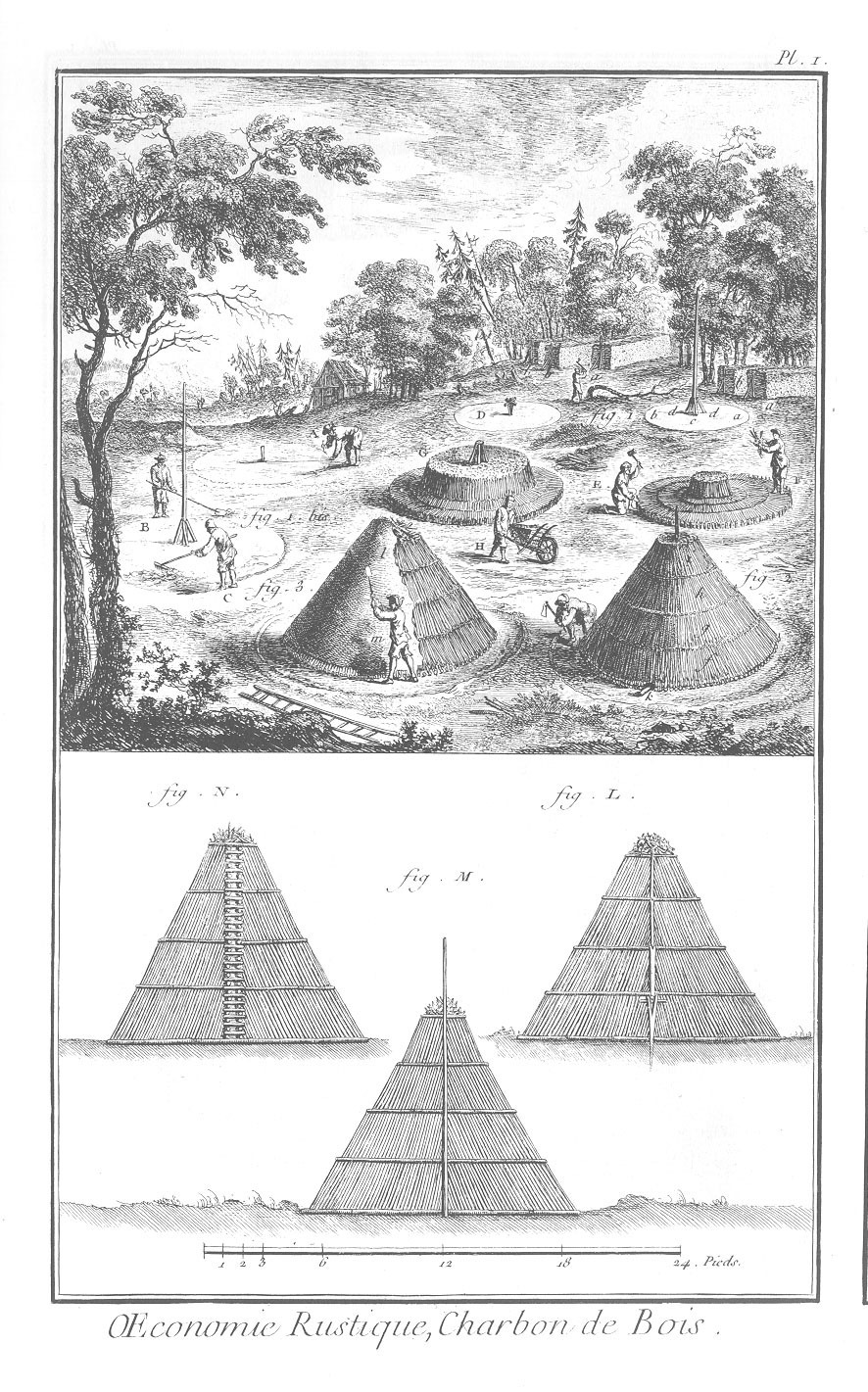

Agriculture and the Rural Economy – Charcoal

Source: "Agriculture and the Rural economy – Charcoal." The Encyclopedia Collaborative Translation Project. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2010. Web. <http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0001.346>. Trans. of "Agriculture et économie rustique – Charbon de bois," Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 1 (plates). Paris, 1762.

Note: Workers are building ovens in a clearing near a wood in order to begin making charcoal. We see various stages in their construction. In the 1820s charcoal makers had a reputation for having radical republican and liberal political views which were repressed by the conservative restored monarchs of France. They were know as the "Carbonari."

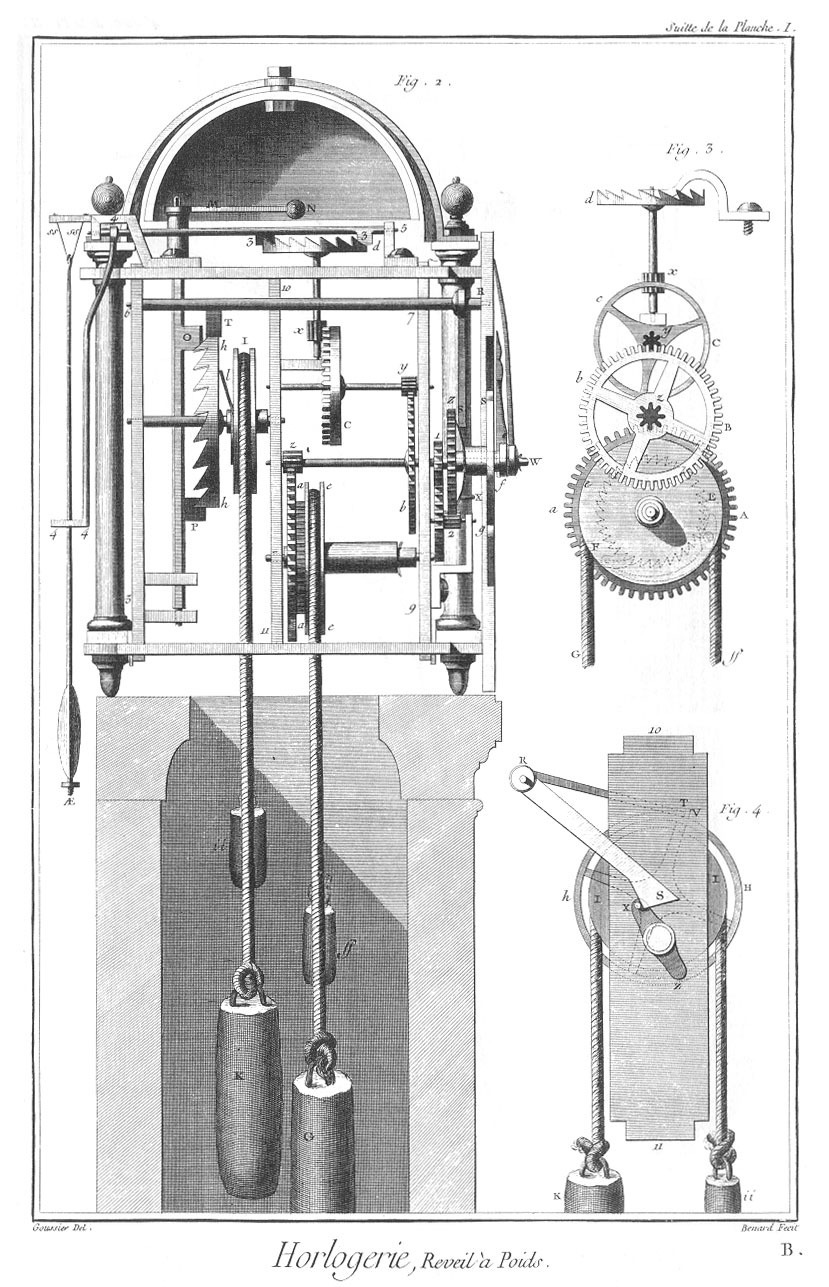

Clock Making

Plate I Continued: Clock Making, Weight-Woven Clock

Source: "Clock making – [1] First section." The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Translated by Charles Ferguson. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2010. Web. <http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0001.465>. Trans. of "Horlogerie – [1] Première section," Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 4 (plates). Paris, 1765.

Note: Clocks and clockwork fascinated many 18th and 19th century thinkers. Many of them conceived the universe itself to be arranged like a clock designed and built by some universal clockmaker who, once the clock started ticking, could be left alone to function on its own without any further intervention (such as William Paley). The inspiration for this came from mathematicians and astronomers like Newton whom Philosophes like Voltaire much admired. In the mid-19th century the economist Frédéric Bastiat had a theory of society which was a "mechanism" like a clock with its own cog wheels, springs, and source of movement. Once his "social mechanism" began working the best policy for a government to follow was that of "laissez-faire" or leaving it completely alone.

Quote from Encyclopedic Liberty:

Invention (Arts and Sciences). A general term which can be applied to everything that is found, invented, or discovered, and which is of use or interest in the arts, sciences, and crafts. To some extent this term is synonymous with "discovery," though less striking ...

We owe inventions to time, pure chance, to lucky and unforeseen speculations, mechanical instincts, as well as to the patience and resourcefulness of those who work.

The useful inventions of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries did not at all result from the researches of those who are known as wits in polite society, nor did they come from speculative philosophers. They were the fruit of that mechanical instinct with which nature has endowed some men, independent from philosophy. ...

... the most interesting and useful things that we possess today in the arts were not found in the state in which we see them now. Everything was discovered in rough form or in parts and has been gradually brought to greater perfection. At least this seems to be the case for those inventions of which we have spoken, and it can be proven for the invention of glass, the compass, printing, clocks, mills, telescopes, and many others.

... that a shorter or longer time lapse was needed to perfect the inventions which originally, in uncivilized centuries, were the products of chance or mechanical genius. ...

The invention of windmills (perhaps originating in Asia) became successful only when geometry perfected the machine, which is based entirely upon the theory of compound movement.

How many centuries have elapsed between the moment when Ctesibius made the first watch run by a movement, probably around 613 in Rome, and the most recent pendulum clock made in England by Graham or in France by Julien Le Roi. Did not Huygens or Leibniz and many others contribute to their perfection? ...

... all those who, thanks to their astuteness, their labors, their talents, and their diligence, will be able to combine research and observation, profound theory and experimentation, will continually enrich existing inventions and discoveries and will have the glory of paving the way for new ones. ...

For the success of this enterprise, however, it is necessary that an enlightened government be willing to grant it a powerful and constant protection against injustice, persecution, and the calumny of enemies. [jaucourt, "Invention ," vol. 8 *1765).]

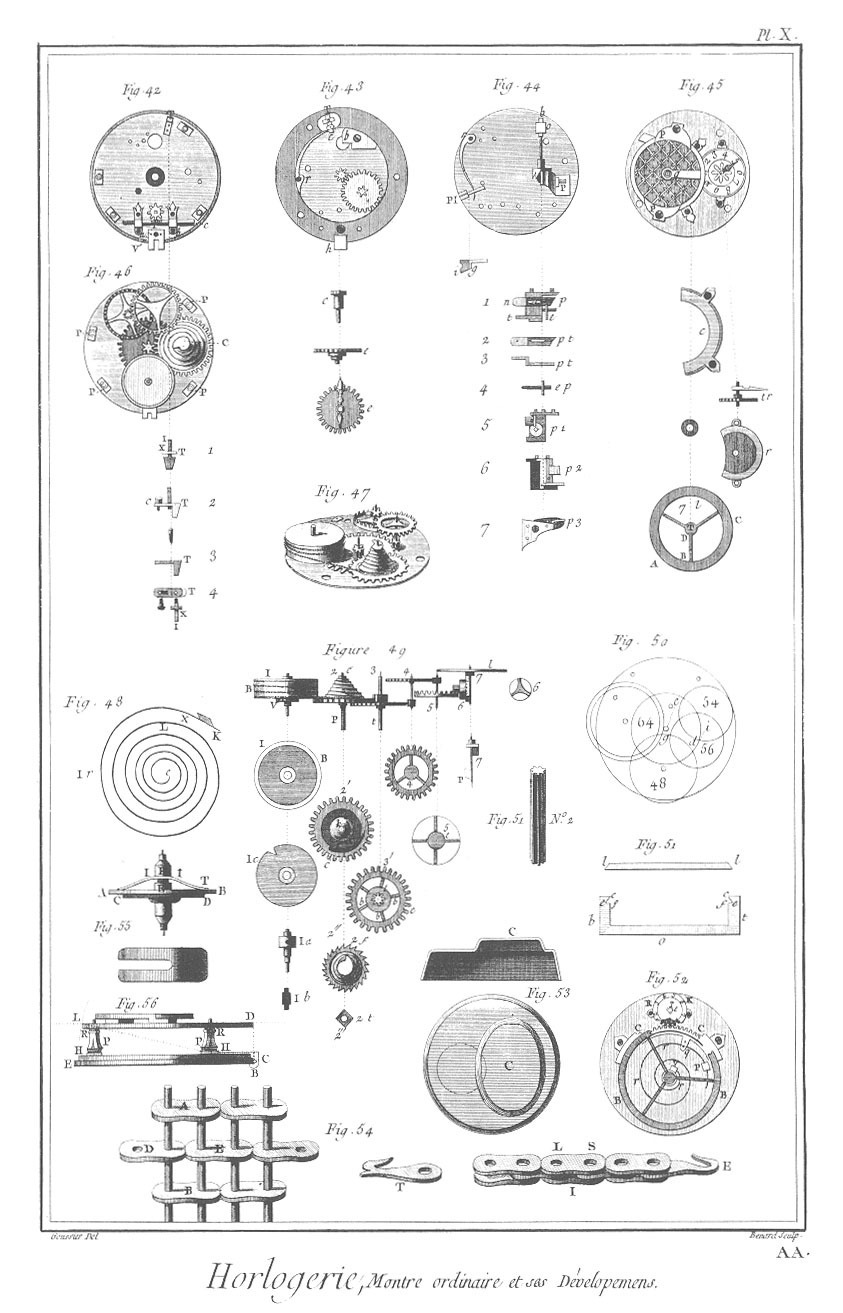

Plate X: Clock Making, Simple Watch and its Developments

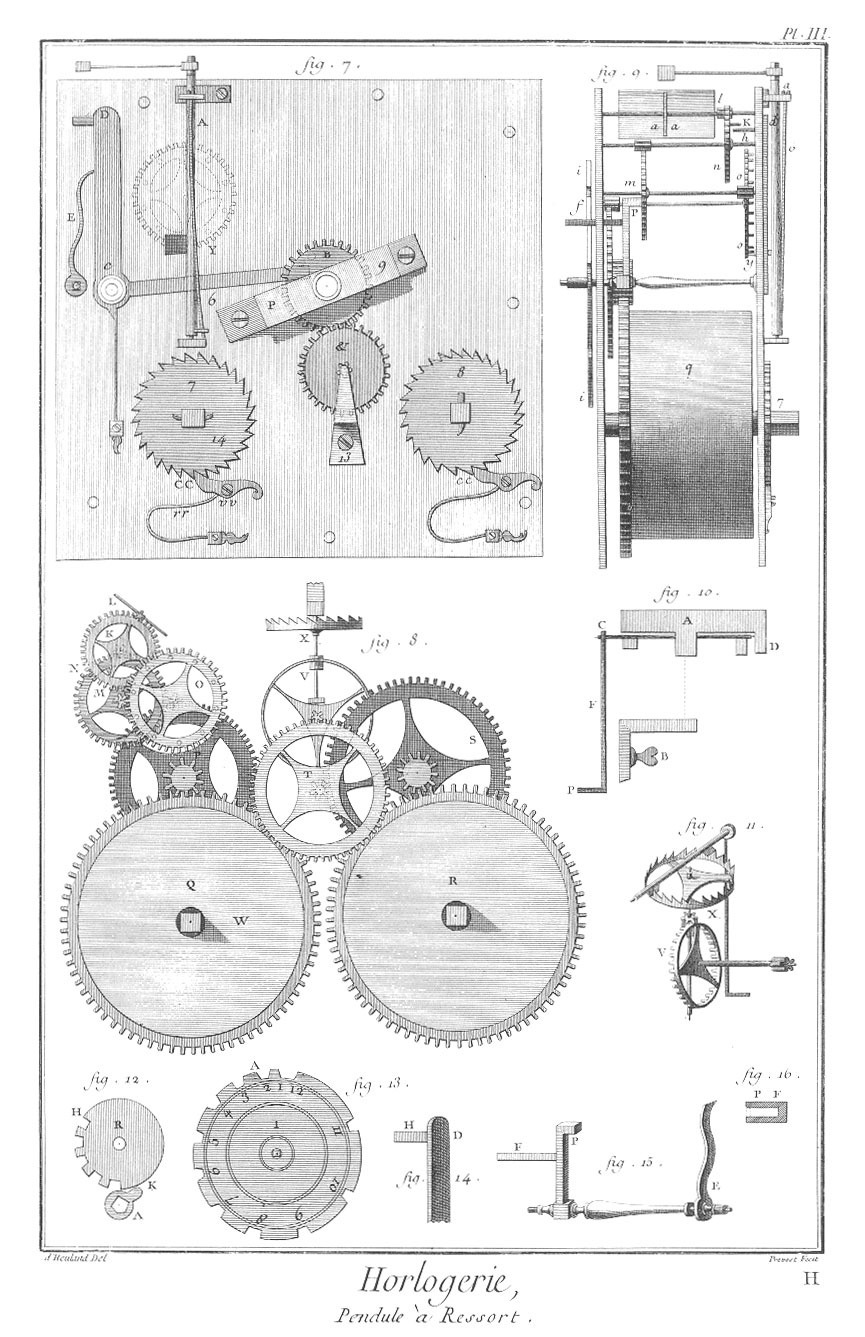

Plate III: Clock Making, Spring-Driven Clocks

Coin minting

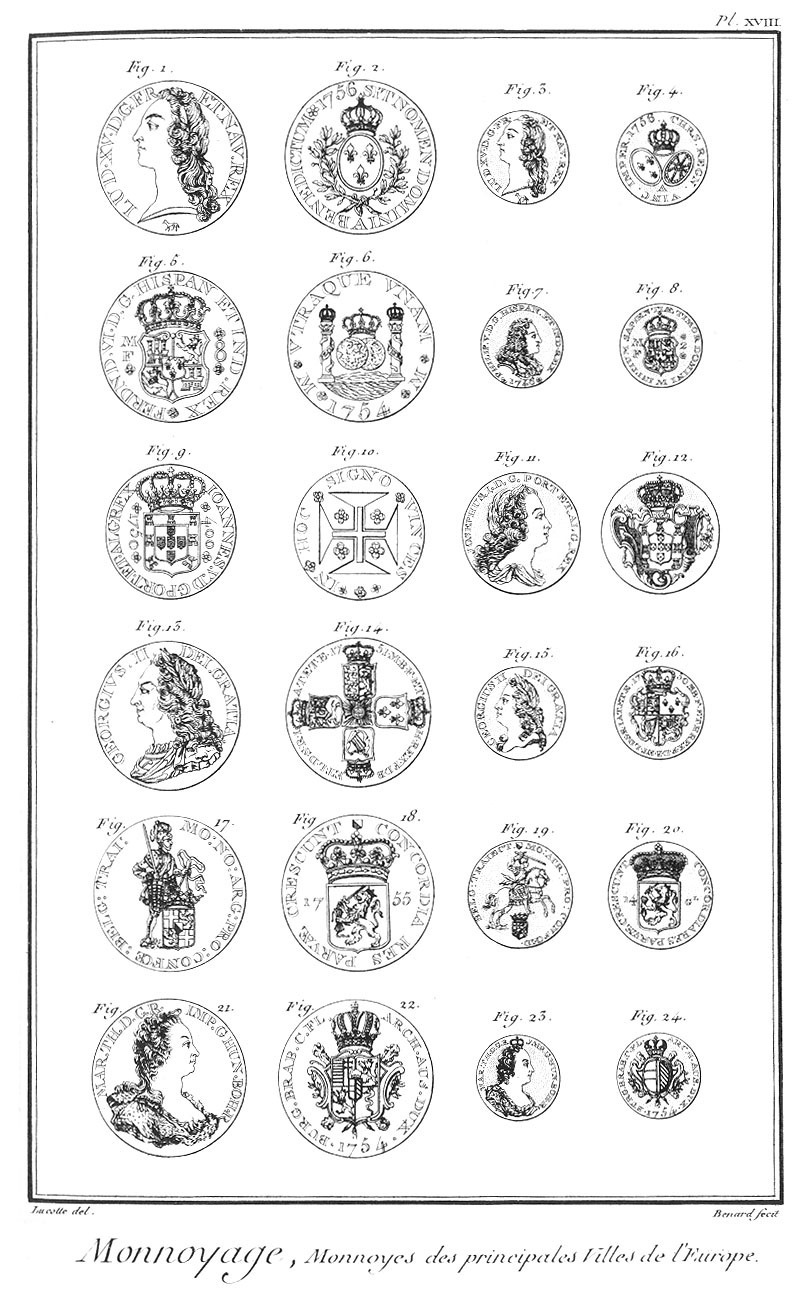

Plate XV: Minting, Coining Press

Source: "Minting." The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2010. Web. <http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0001.577>. Trans. of "Monnoyage," Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 8 (plates). Paris, 1771

Note: In the Encyclopedia there were many images relating to the production of money (coins) which suggests it was very important to them because it was a very complex procedure of mining, refining, smelting, and pouring the metal, and then stamping the coins. Also, money was the cornerstone of the rapidly developing new commercial and industrial society which was taking shape around them. Money in the 18th century was primarily coins which were made of gold, silver, and copper which were stamped with the image of the ruling monarch. The issuing of money was largely in the hands of the state (hence the image of the king) although there were some experiments with free banking (private banks issuing their own currency) in places like Scotland, and metal coins were widely accepted all over Europe and the Americas as they were freely convertible. The coin press was operated by hand. Note the muscular, even classical pose of the men on the left.

Quote from Encyclopedic Liberty:

Aside from the general convenience of free and easy loans for the people, I regard it as one of the advantages of these establishments (savings banks for the people) that they would be so many known offices where one could with confidence deposit sums that one is not always in a position to place usefully, and that one sometimes finds awkward. How many misers are there who, fearing for the future, don't dare part with their money, and who, despite their precautions, always have to fear theft, fire, pillage, &c.? How many workers, how many domestics and other isolated people are there who, having saved a small sum—ten pistoles (a hundred crowns, more or less)—do not in fact know what to do, and are with reason apprehensive about dissipating or losing it? I thus find it advantageous in all these cases to be able to deposit any sum whatsoever with certainty, and to be free to withdraw it at will. Countless sums, small and large, that today remain inactive would thereby be made to circulate throughout the public. On the other hand, the individual depositors would avoid many anxieties and swindles; moreover, they would be less liable to lend their money unsuitably or spend it foolishly. Thus, each person would recover his funds or his savings if his business was in order, and most workers and domestics would become more orderly and economizing. [Article by Faiguet, "Savings," vol. 5 (1755).]

Plate XVIII: Minting, Coins of the Main Cities of Europe

.

Note: We see the images stamped on the coins of France, Spain, Portugal, England, Holland. Figues 1-2 is a silver écu from France; figures 3-4 is a gold "Louis" from France. We can see the head of George II on the English coins 13-16.

The Cotton Industry

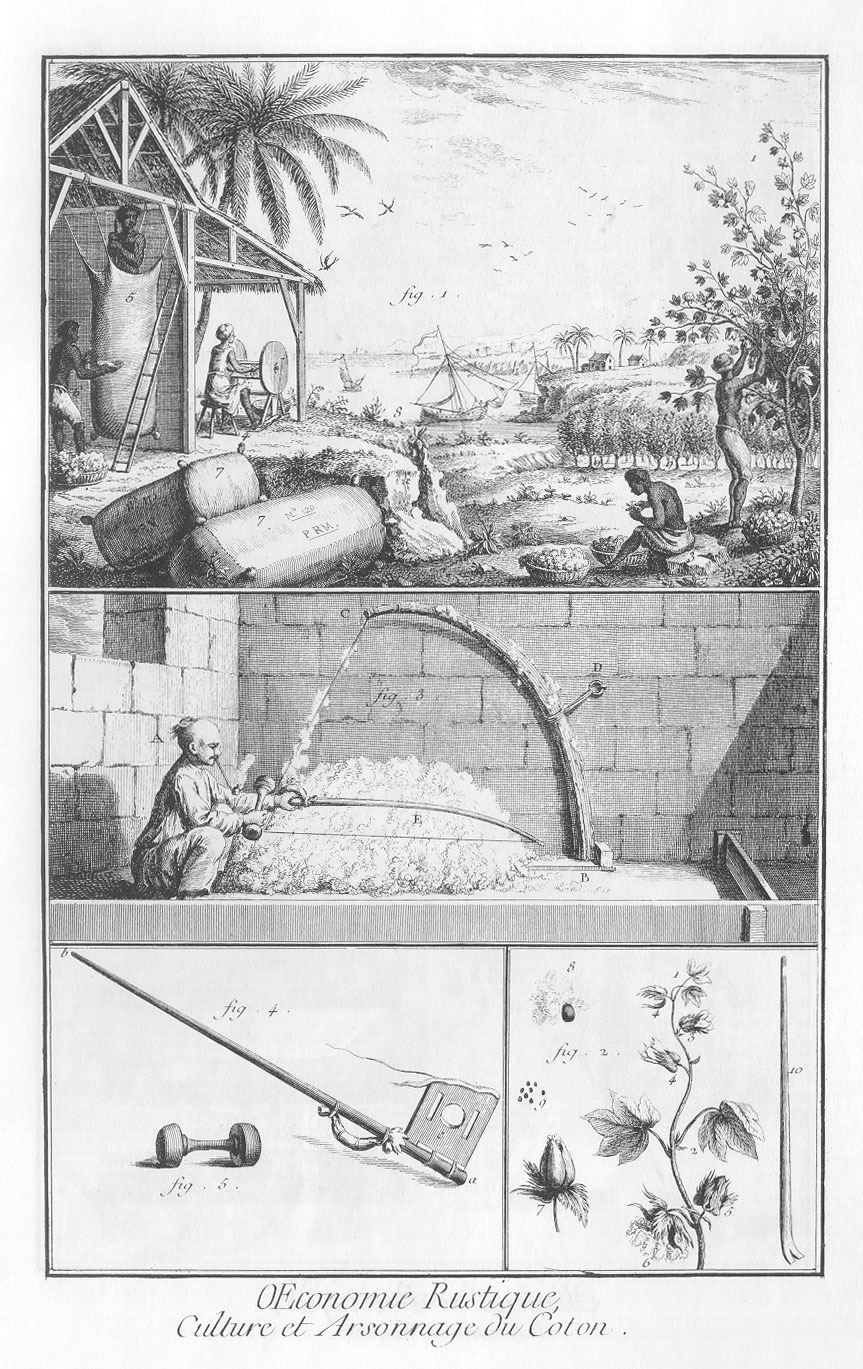

Agriculture and the Rural Economy – Cotton growing and cleaning

Source: "Agriculture and rural economy – Cotton culture and cleaning." The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2010. Web. <http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0001.338>. Trans. of "Agriculture et économie rustique – Culture et arsonnage du coton," Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 1 (plates). Paris, 1762.

Note: Note in the top panel the African slaves picking and baling the cotton on an unnamed "American Island"; in the middle panel a Chinese man is cleaning the cotton and smoking a pipe (possibly filled with opium). The Philosophes opposed slavery and created some of the first organizations to lobby for its abolition, such as "La Société des Amis des Noirs" (The Society of the Friends of the Blacks) (founded 1788).

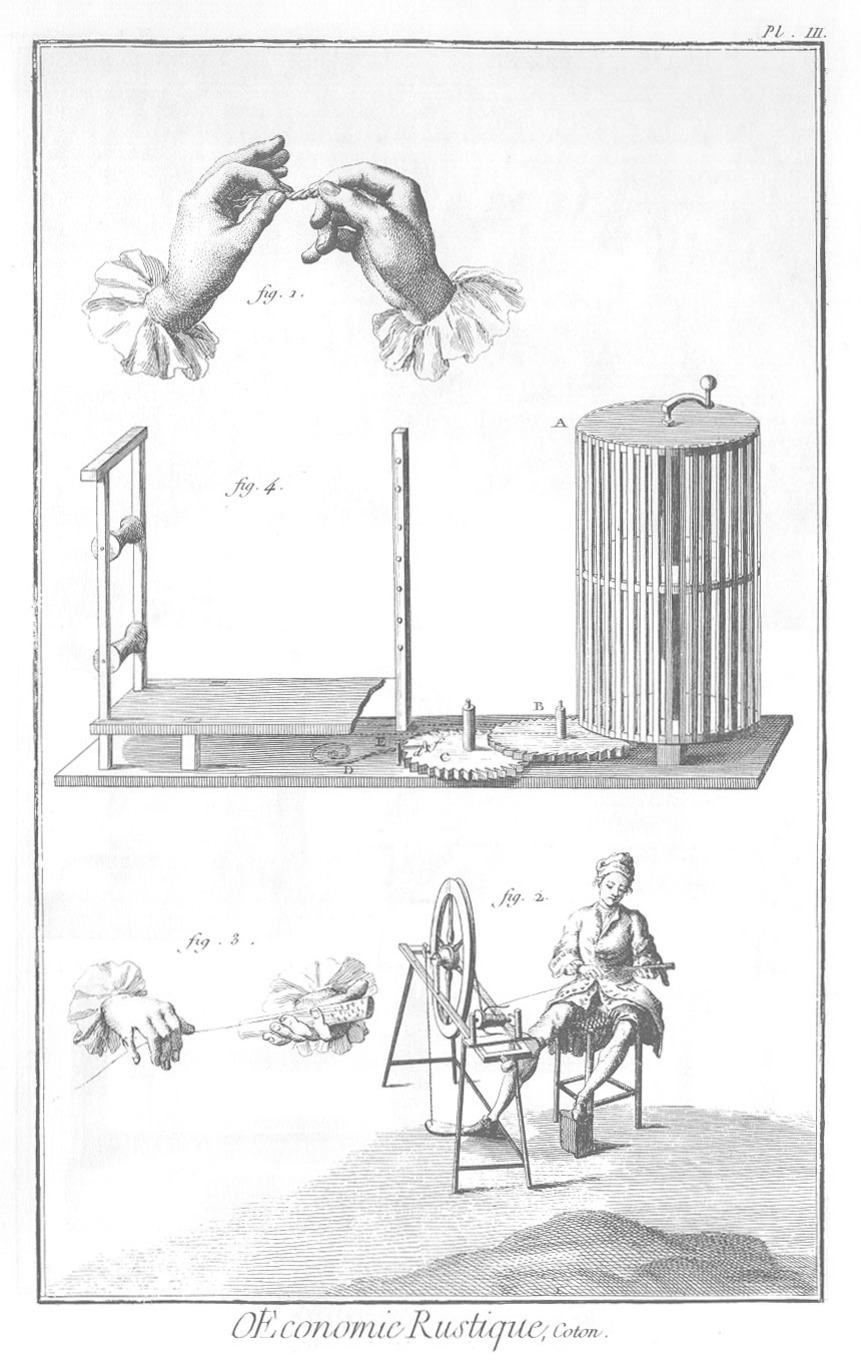

Plate III: Rural Economy, Cotton - Lustering and Spinning the Cotton

Source: "Agriculture and rural economy – Processing and uses of cotton." The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2010. Web. <http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0001.339>. Trans. of "Agriculture et économie rustique – Travail et emploi du coton," Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 1 (plates). Paris, 1762.

Note: This is work done by women. The detail of the hands shows frilly cuffs which may not be appropriate clothing to wear for this kind of work.

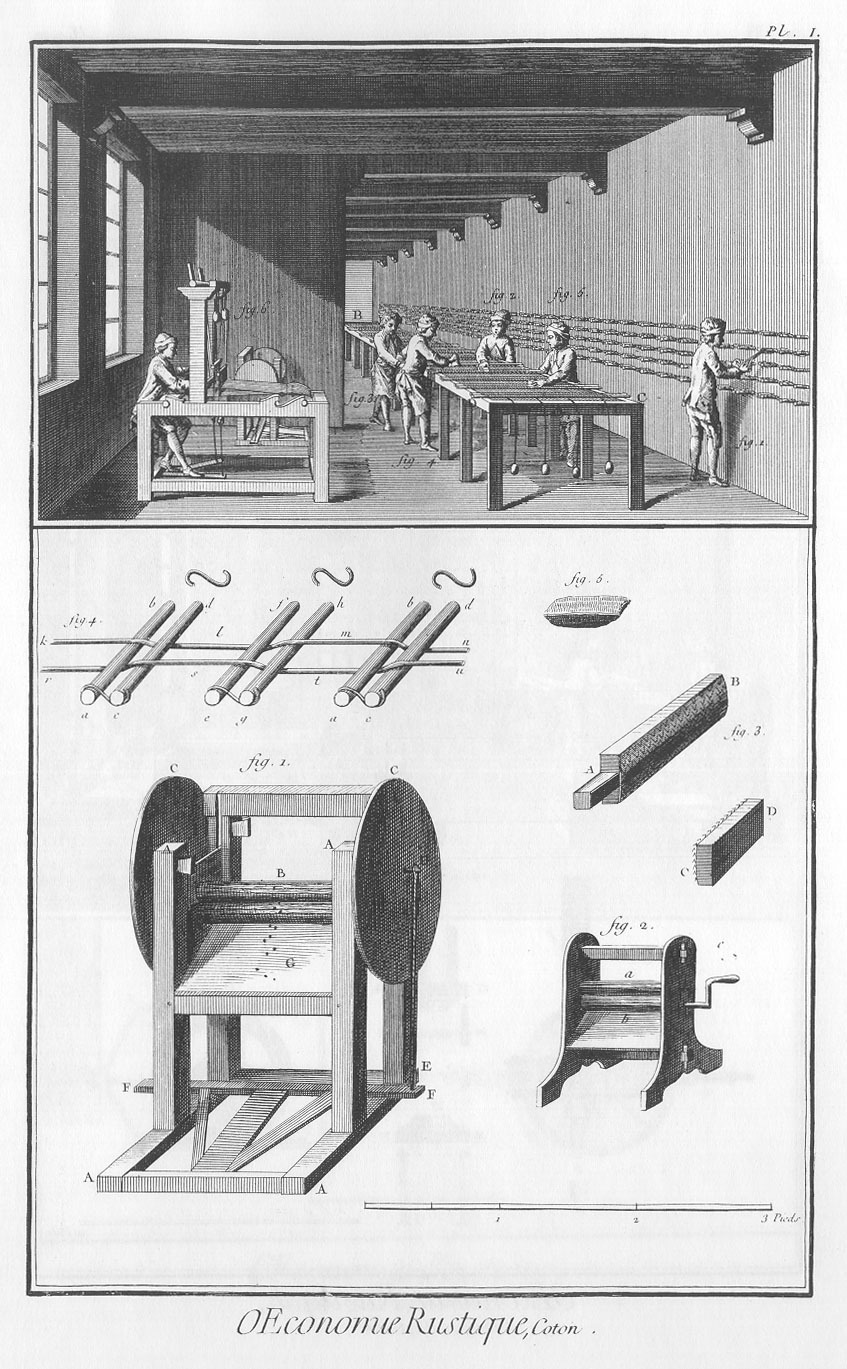

Plate I: Rural Economy, Cotton - the interior of a cotton factory

Source: "Agriculture and rural economy – Processing and uses of cotton." The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2010. Web. <http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0001.339>. Trans. of "Agriculture et économie rustique – Travail et emploi du coton," Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 1 (plates). Paris, 1762.

Note: This work is still done by hand as it predates the introduction of the water and steam powered machinery which would transform cotton manufacturing in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

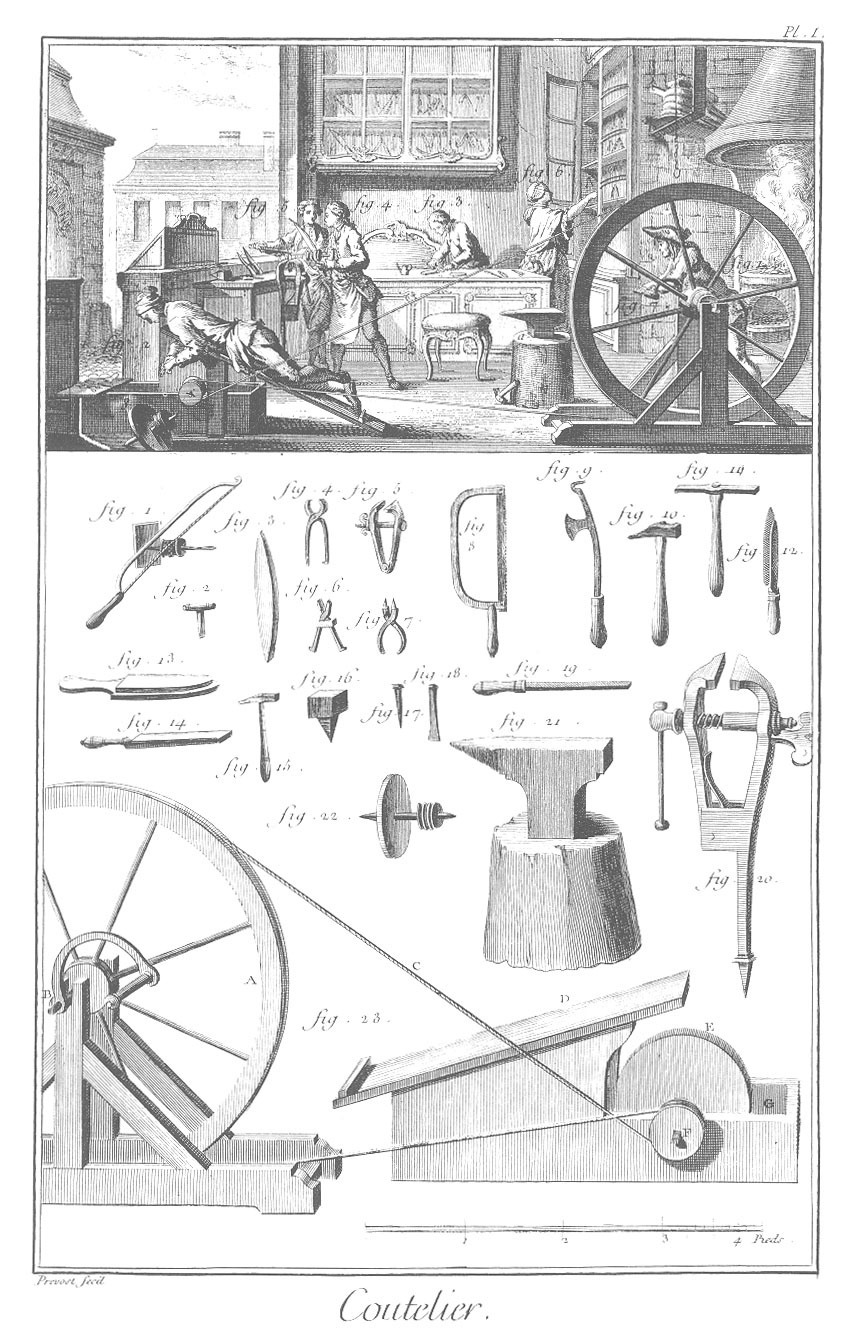

Cutler

Plate I: Cutlery

Source: "Cutlery." The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2010. Web. <http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0001.433>. Trans. of "Coutelier," Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 3 (plates). Paris, 1763.

Note: The workshop of a cutler in Paris. The worker on the left who is lying on a board is polishing a knife. We have included this image because Diderot was the son of a cutler and may well have worked in his father's shop when he was young. I imagine he might have had to create a "masterpiece" to show he was qualified to enter the highly restricted guild of master cutlers.

Quote from Encyclopedic Liberty:

[On restrictive entry requirements to enter into a Guild.] Masterpiece , one of the most difficult works in a profession, executed by candidates wishing to join a guild or corporation, after completing a period as an apprentice and journeyman, according to the rules of the guild. Each corporation has its own masterpiece, which is carried out in the presence of doyens, syndics, senior members, and other officers and dignitaries of the corporation. It is presented to the guild's members, who examine it before it is registered. Some corporations allow the aspiring master craftsman to choose between several different masterpieces, while others ask for more than one. See the rules of these corporations concerning the prevailing norm for the reception of master craftsmen. The masterpiece in architecture is a classic exercise, such as designing a slanting arch, the top and sides of which hold up a cylindrical ceiling; the carpenters' masterpiece is a curved stair stringer; silk weavers, whether to be received as companions or as masters, must restore a loom to its working order, after the masters and syndics have brought about whatever changes to it they see fit, as, for example, untying the strings or breaking the threads of the chain at irregular intervals. It is hard to see the utility of the masterpiece. If the candidate can do his job well, then it is a waste of time examining him. If he cannot do his job well, then it should not stop him from joining a corporation, since he will only be harming himself. A reputation as a bad worker will soon force him to give up a job in which he will inevitably face ruin if he finds no work. To be convinced of the truth of these remarks, one needs only know a little of what happens at examinations. Nobody can be a candidate who has not passed through the preliminaries, and it is impossible for anyone not to have learned something of the trade in the four or five years that the preliminaries last. If the candidate is the master's son, he is generally exempted from doing a masterpiece. Everyone else, even the town's most skillful workers, will find it hard to produce a masterpiece that is acceptable to the guild, if ever they are disliked by the guild. If they are liked, on the other hand, or if they have money, even if they know nothing whatsoever about the job, then they can either bribe the people supervising them during the execution of the masterpiece, carry out a poor piece of work that will be received as a masterpiece or present an excellent piece of work done by someone else. It is clear that such practices do away with any advantages that can be claimed for the masterpiece or for guilds, and yet guilds and corporate bodies for manufacturing continue to exist all the same. [Diderot, "Masterpiece (Chef-d'Œuvre)," vol. 3 (1753).]

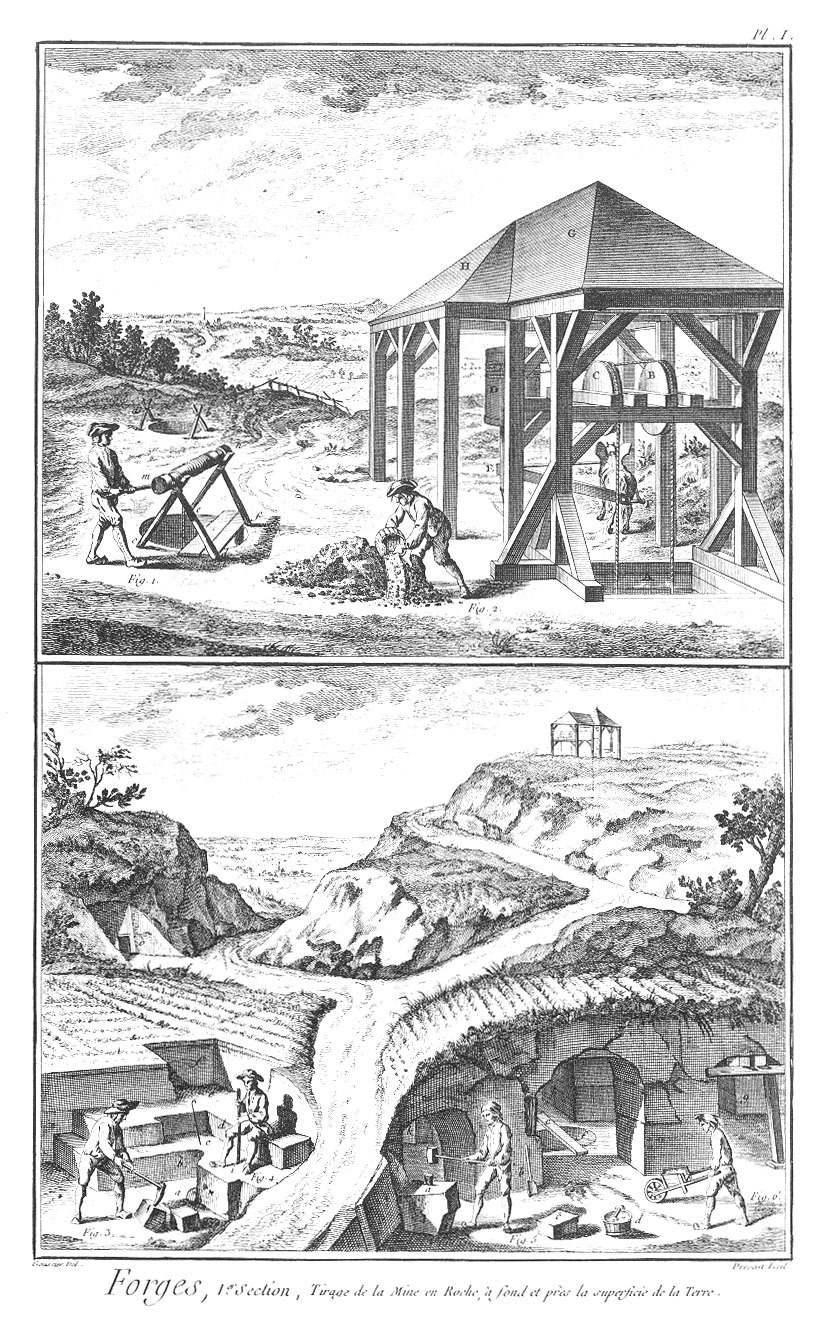

Mining, Transporting and Refining Iron Ore

Plate I: Forges, First Section, Ore Extraction from Underground Mine and Surface Mine

Source: "Forges or the art of making iron – [1] First section." The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Translated by Jeremy Platt. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2010. Web. <http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0001.452>. Trans. of "Forges ou art du fer – [1] Première section," Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 4 (plates). Paris, 1765.

Note: The top panel shows two men at the top of the hill winching ore to the surface in buckets and sorting the ore. To the right we can see a mule or donkey which is used for heavy lifting. The bottom panel shows a cutaway view of the side of a hill or mountain which is being mined for iron ore.

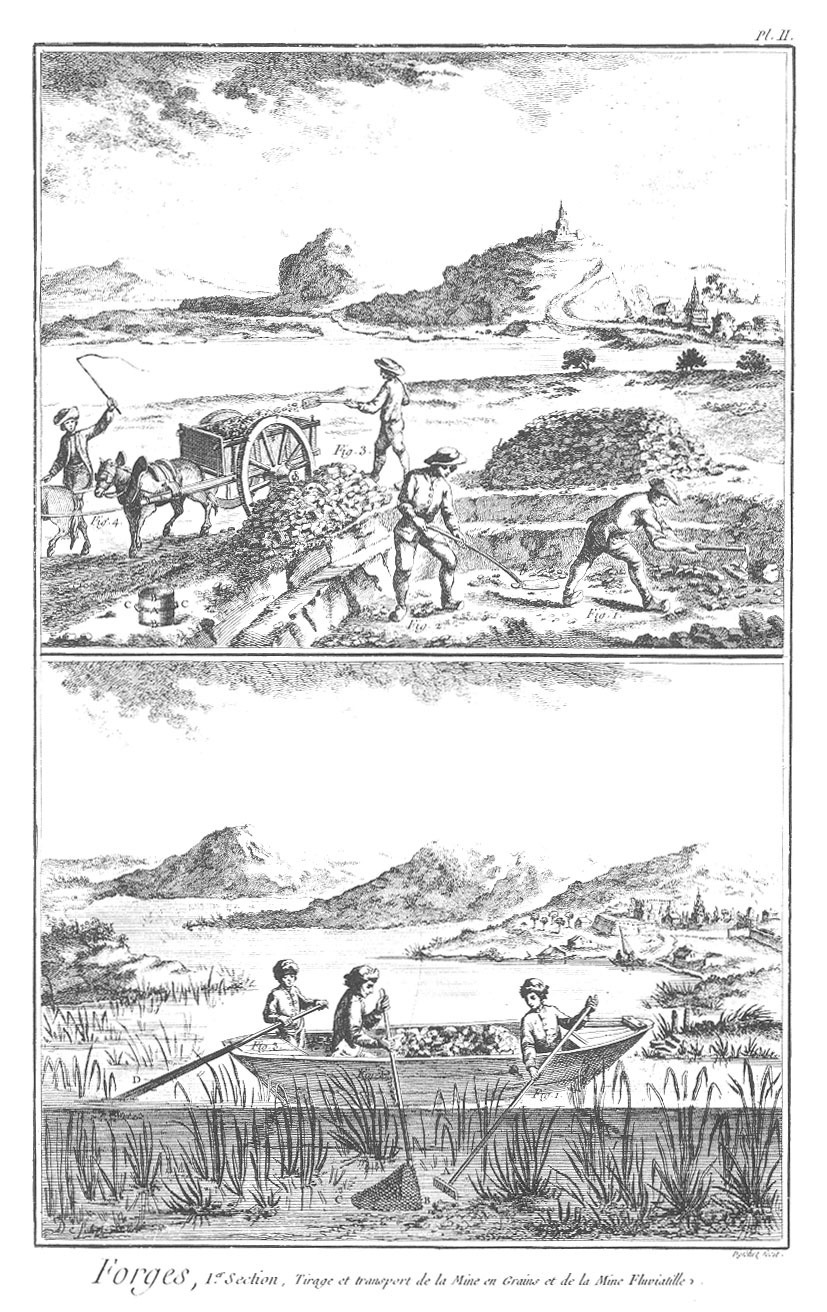

Plate II: Forges, First Section, Extraction and Shipping of Surface Bed Ore and River Ore

Note: Before the introduction of steam engines and the railway in the late 18th and early 19th centuries heavy iron ore had to be carted by horse (top panel) or by boat. The bottom panel shows an unusual way of "mining" on a river or lake. Two women are searching for ore on the bed of a lake and pushing any they find into a net or scoop. It is interesting to note that men do the shovelling and carting by horse, while women and possibly a child do the "fishing" for ore.

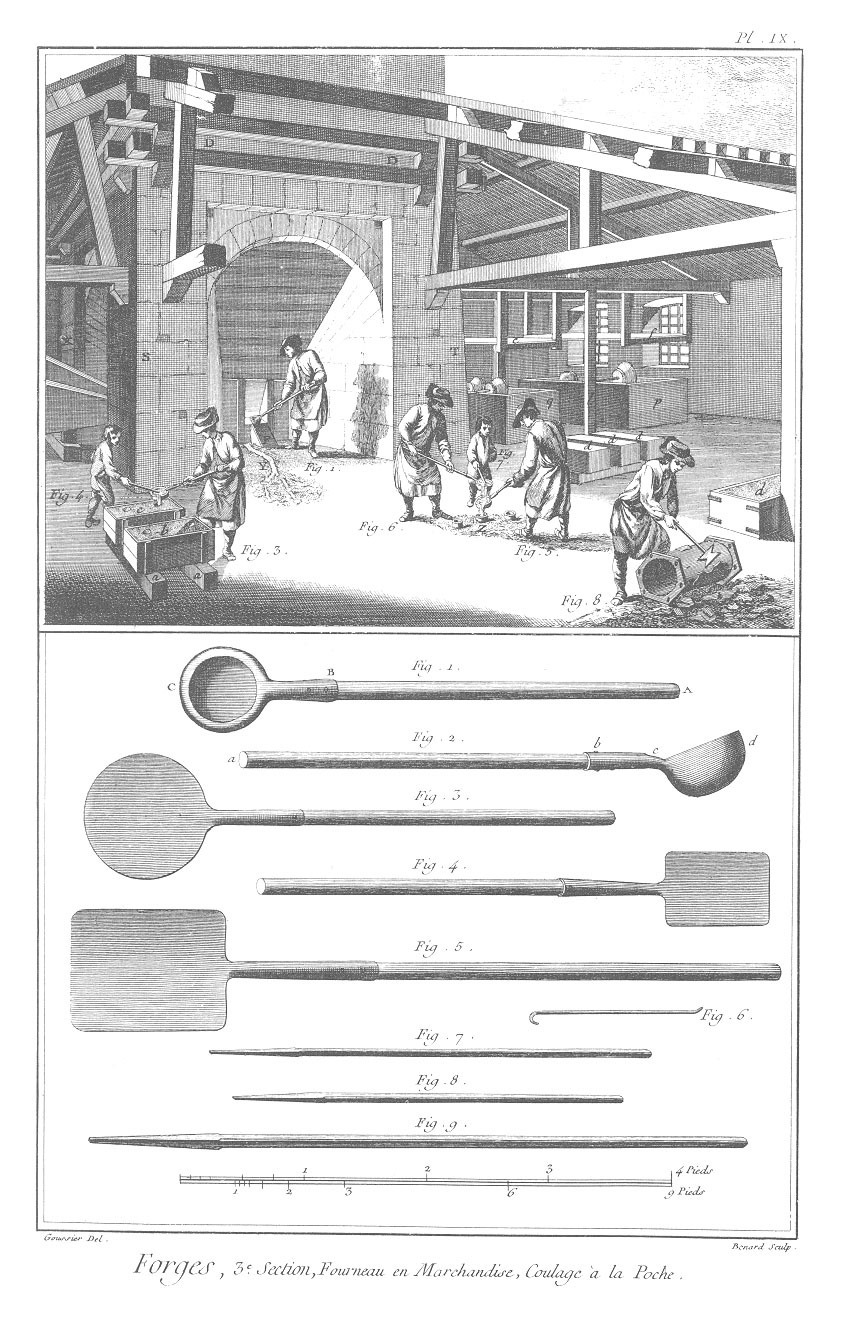

Plate IX: Forges, Third Section, Pouring with Ladles

Source: "Forges or the art of making iron – [3] Third section." The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Translated by Jeremy Platt. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2010. Web. <http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0001.454>. Trans. of "Forges ou art du fer – [3] Troisème section," Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 4 (plates). Paris, 1765.

Note: A group of workers, 5 men and 2 children (boys) in a forge are ladling molten iron from the furnace into molds made out of sand. The man at the bottom right is breaking the mold which was used to cast a piece of pipe. Note the use of children in this process.

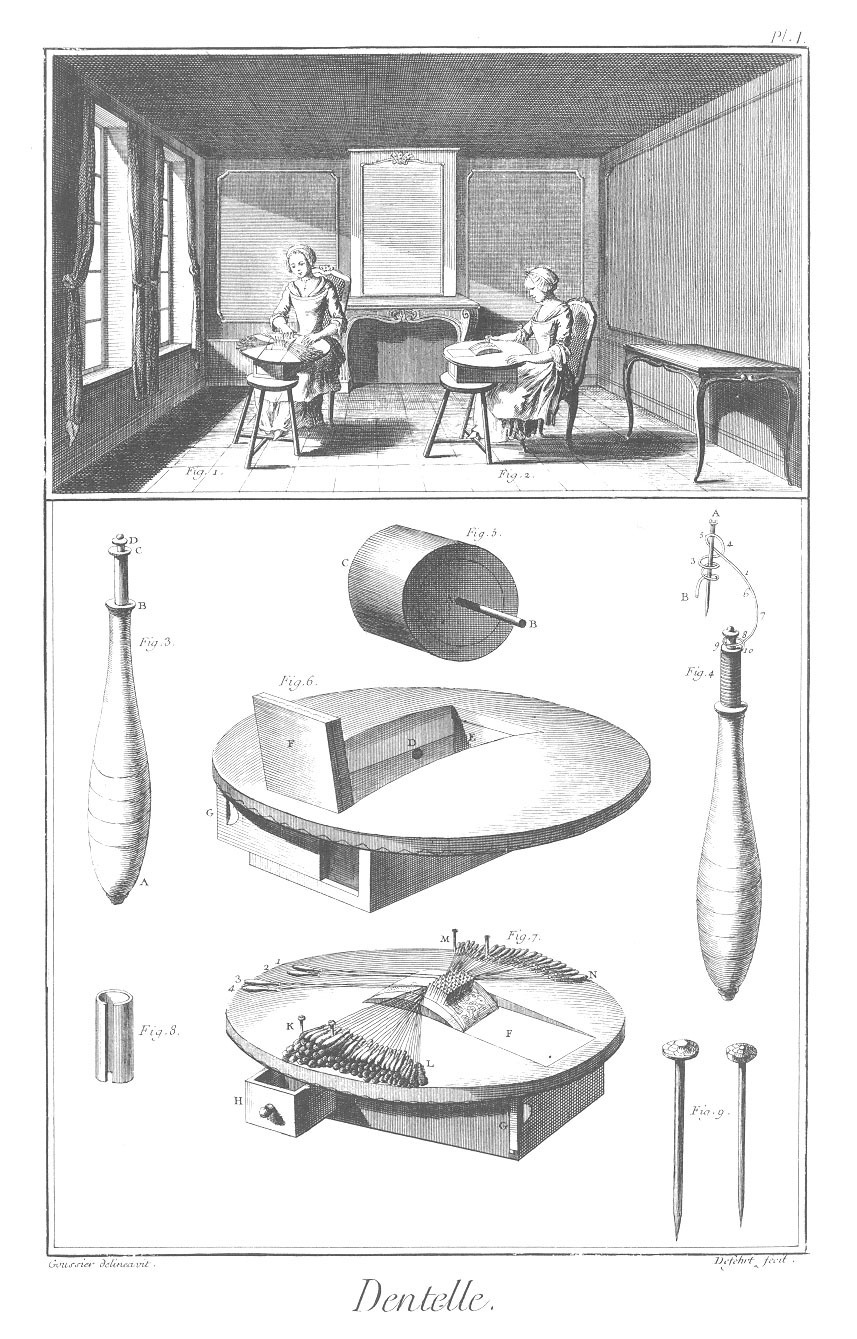

Lace making

Source: "Lace making and stitch work." The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2010. Web. <http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0001.435>. Trans. of "Dentelle et façon du point," Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 3 (plates). Paris, 1763.

Note: Two women are working in what looks like a private home (with home furnishings) making lace. The bottom panel shows the tools of their trade.

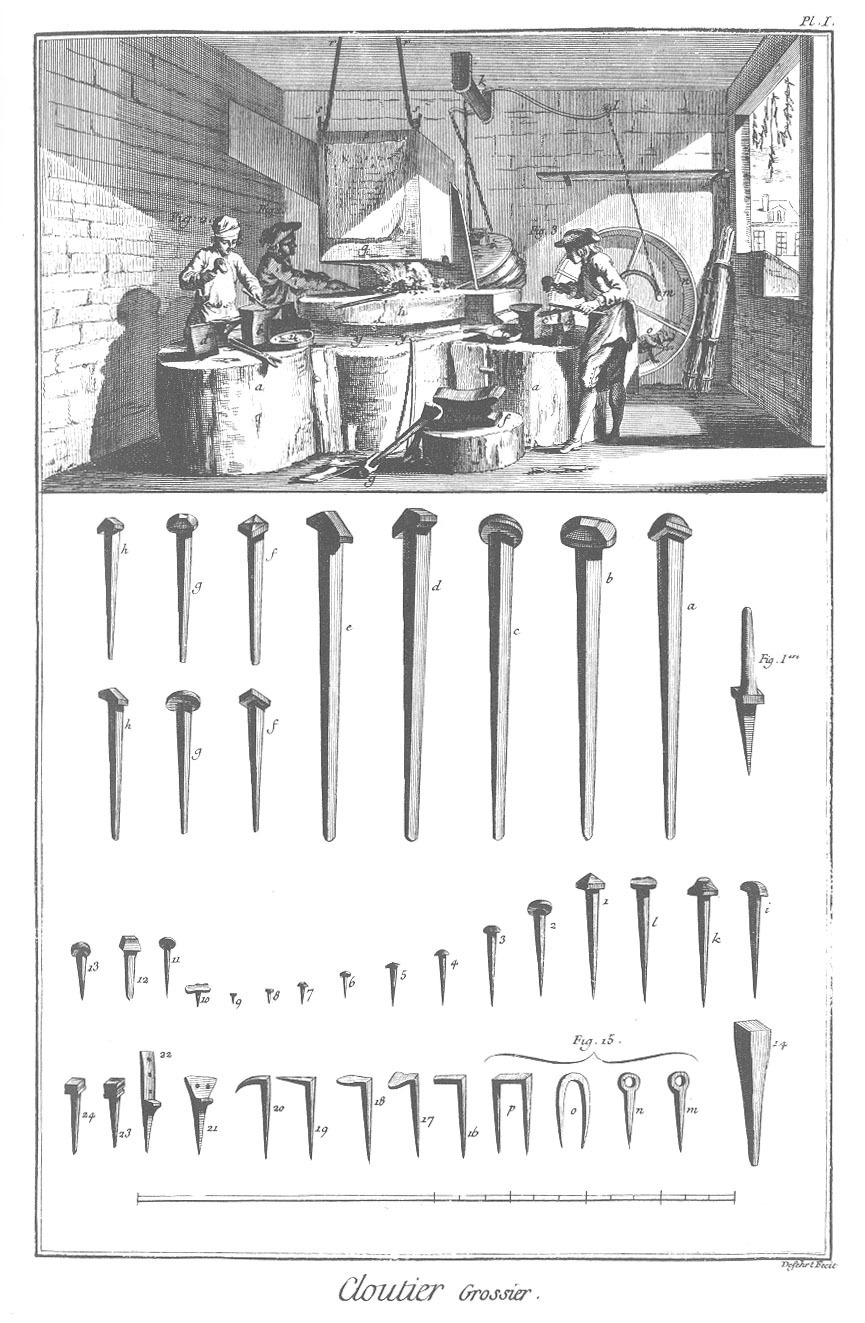

Nail making

Source: "Heavy nail making." The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2010. Web. <http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0001.426>. Trans. of "Cloutier Grossier," Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 3 (plates). Paris, 1763.

Note: This image is a complement to the ones on pin making. See below for details. Note the small size of the nail maker's workshop which is contrasted with the striking variety of nails which they make.

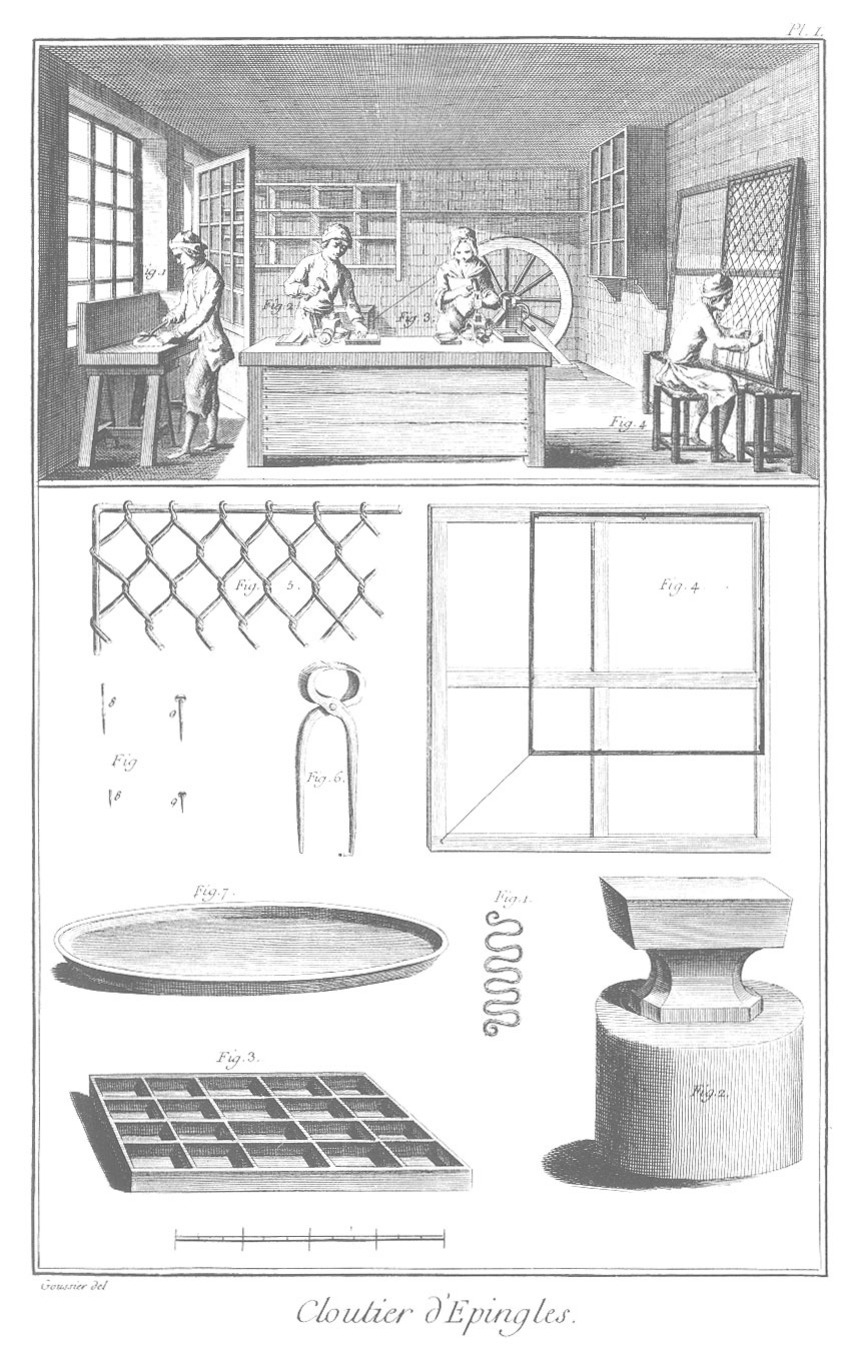

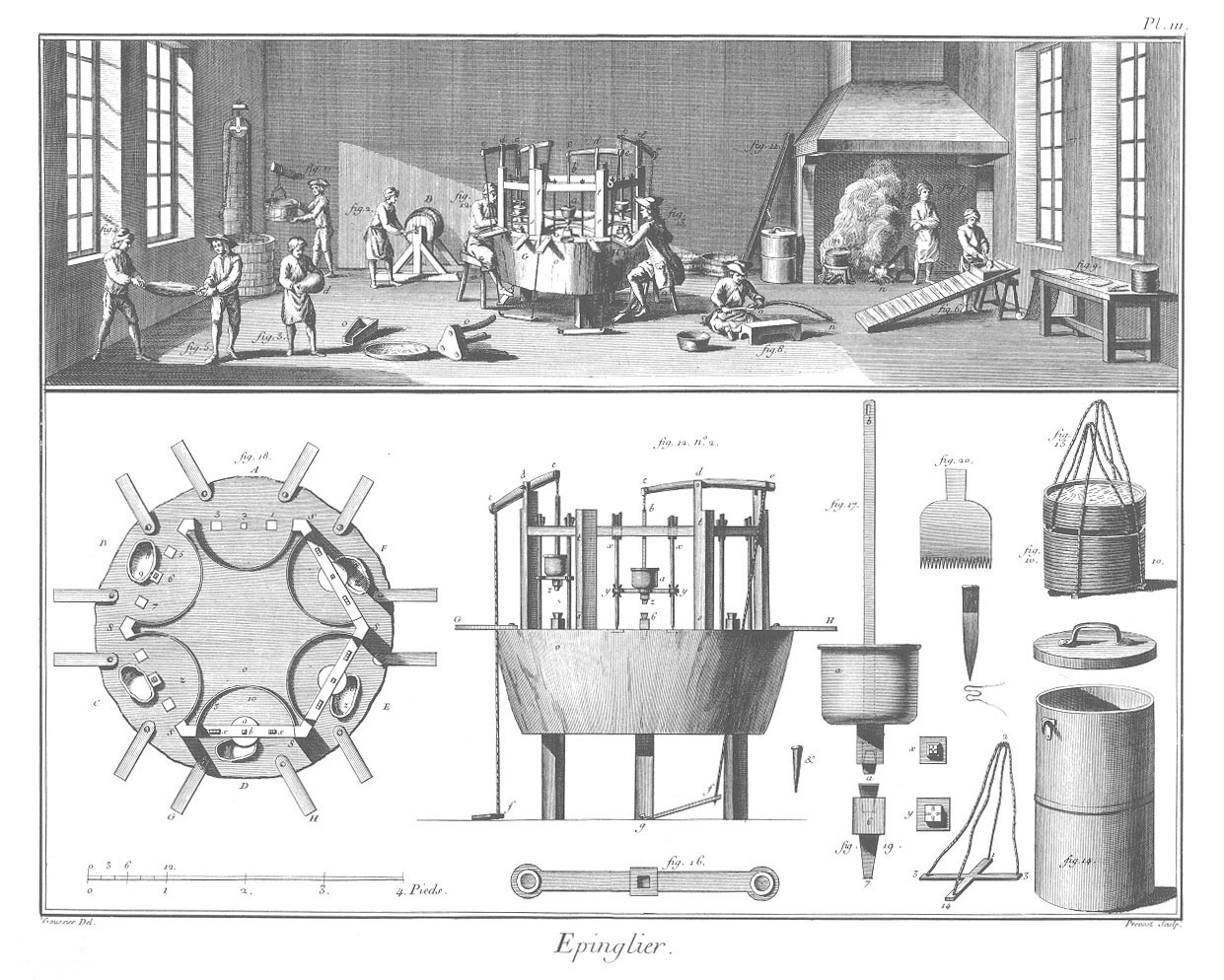

Pin Making

Plate I: Pin Making

Source: "Pin making." The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2010. Web. <http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0001.427>. Trans. of "Cloutier d'épingles," Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 3 (plates). Paris, 1763.

Note: A small workshop where four people are making pins. The tasks include making a mesh of long wires which create a uniform sized piece of wire for cutting, cutting the wire, sharpening the ends, making the heads by flattening some metal with a hammer.

Quote from Encyclopedic Liberty:

[The author Deleyre]: Of all mechanical works, the pin is the thinnest, commonest, and cheapest. And yet, it is one of those that demand perhaps the most combinations.Thus it happens that art as well as nature displays its prodigies in small objects, and that industry is as limited in its focus as it is wondrous in its resourcefulness. For a pin undergoes eighteen operations before becoming an item of trade.

[Diderot's editorial comment]: This article is by M. Delaire, who was describing the manufacture of the pin in the workers' actual workshops, based on our designs, at the same time that he was publishing in Paris his analysis of Chancellor Bacon's sublime and profound philosophy. Bacon's work, combined with the foregoing description, will prove that a good mind can sometimes enjoy the same success rising to the highest contemplations of philosophy as it does descending to the most minutely detailed mechanics. Moreover, whoever has some acquaintance with the views the English philosopher held as he was composing his works will not be surprised to see his disciple pass without disdain from his research on the general laws of nature to the least important use of nature's productions. [Article "Pin", vol. 5 (1755)]

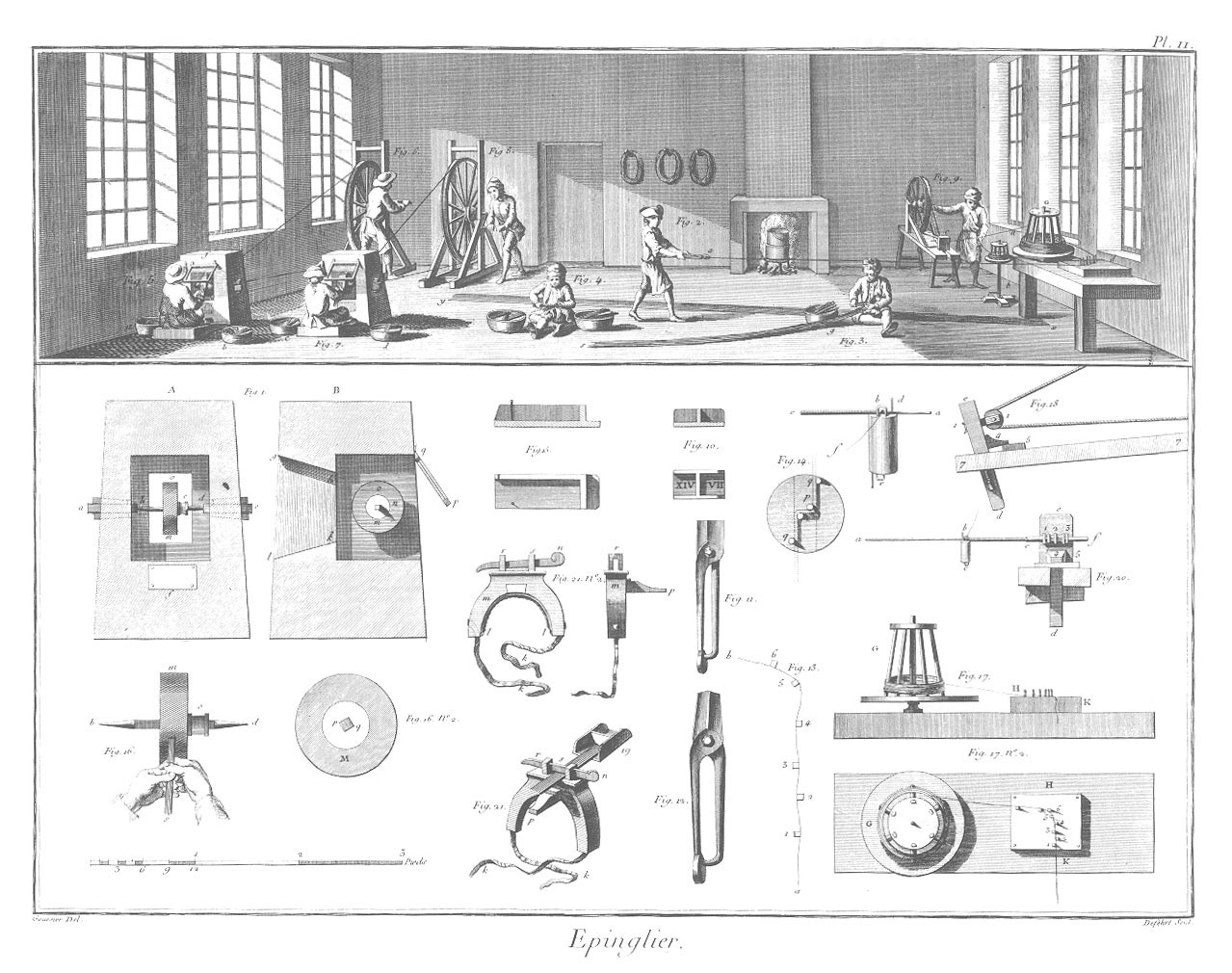

Plate II: Pinmaker

Source: "Pinmaker." The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2010. Web. <http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0001.445>. Trans. of "Epinglier," Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 4 (plates). Paris, 1765.

Note: This and the plate below show much larger pin factories. Above, there are only four workers. Here there are 8 and below there are 10. We have included these images because of the use made of this example by Adam Smith (and others) to explain how the specialisation and division of labour within the pin factory could dramatically increase output. See also the illustrated essay "Adam Smith and J.B. Say on the Division of Labour" </pages/adam-smith-and-j-b-say-on-the-division-of-labour>. The relevant passage from Smith follows:

To take an example, therefore, from a very trifling manufacture; but one in which the division of labour has been very often taken notice of, the trade of the pin–maker; a workman not educated to this business (which the division of labour has rendered a distinct trade), nor acquainted with the use of the machinery employed in it (to the invention of which the same division of labour has probably given occasion), could scarce, perhaps, with his utmost industry, make one pin in a day, and certainly could not make twenty. But in the way in which this business is now carried on, not only the whole work is a peculiar trade, but it is divided into a number of branches, of which the greater part are likewise peculiar trades. One man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head; to make the head requires two or three distinct operations; to put it on, is a peculiar business, to whiten the pins is another; it is even a trade by itself to put them into the paper; and the important business of making a pin is, in this manner, divided into about eighteen distinct operations, which, in some manufactories, are all performed by distinct hands, though in others the same man will sometimes perform two or three of them. I have seen a small manufactory of this kind where ten men only were employed, and where some of them consequently performed two or three distinct operations. But though they were very poor, and therefore but indifferently accommodated with the necessary machinery, they could, when they exerted themselves, make among them about twelve pounds of pins in a day. There are in a pound upwards of four thousand pins of a middling size. Those ten persons, therefore, could make among them upwards of forty–eight thousand pins in a day. Each person, therefore, making a tenth part of forty–eight thousand pins, might be considered as making four thousand eight hundred pins in a day. But if they had all wrought separately and independently, and without any of them having been educated to this peculiar business, they certainly could not each of them have made twenty, perhaps not one pin in a day; that is, certainly, not the two hundred and fortieth, perhaps not the four thousand eight hundredth part of what they are at present capable of performing, in consequence of a proper division and combination of their different operations. [Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith, edited with an Introduction, Notes, Marginal Summary and an Enlarged Index by Edwin Cannan (London: Methuen, 1904). Vol. 1. </titles/237#Smith_0206-01_237>]

Plate III: Pinmaker

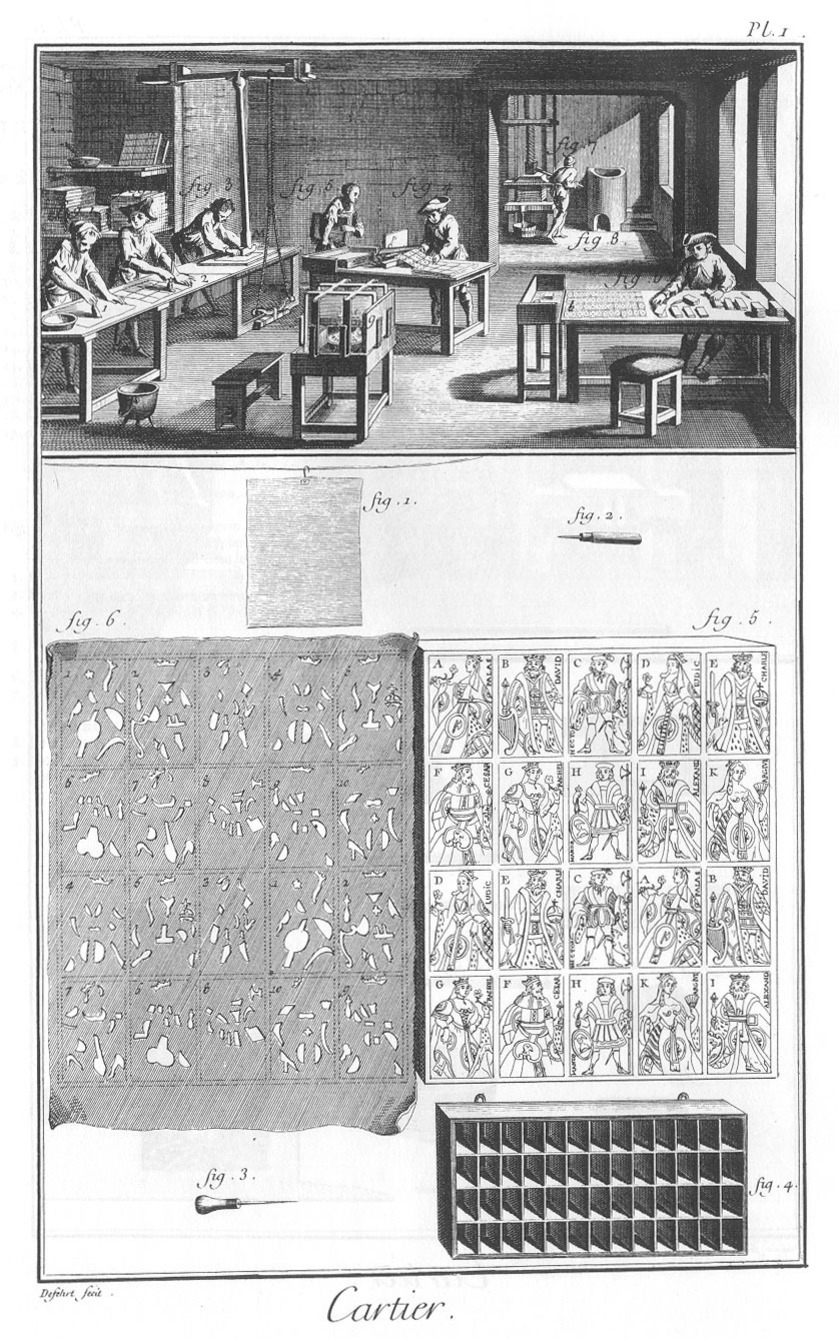

Playing Cards

Plate I: Card Maker

Source: "Card maker." The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2010. Web. <http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0001.405>. Trans. of "Cartier," Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 2 (plates). Paris, 1763.

Note: The interior of a playing card workshop. Note that the cards are printed using stencils which have to be cut out. During the French Revolution some card makers decided to redesign the faces used on the cards since they believed the traditional "Kings," "Queens", and "Knaves" were too monarchical. See our illustrated essay on "New Playing Cards for the French Republic (1793-94)" </pages/new-playing-cards-for-the-french-republic-1793-94>.

Quote from Encyclopedic Liberty:

[Showing the Puritanical side of some of the Encyclopedists.] There you have many means of saving that political men have already lighted upon. But here is another one of which they have not yet scratched the surface, though it is among the most interesting: I am talking about gambling casinos,12 which are manifestly contrary to the national good. But I am talking especially about the taverns which have so multiplied and are so harmful among us that they are the most common cause of the poverty and disorder of the people.

The taverns, properly understood, are a constant occasion for excess and waste, and it would be very useful, from a religious and a political perspective, to abolish the greater portion of them as they come to be vacant. It would be no less important to forbid all settled and recognized persons in each parish to frequent them during work days; to close them with strict precision at nine o'clock in the evening in every season, and finally, to subject all violators to a stiff fine, half of which would go to the informers and half to the inspectors.

It will be said that these regulations, although useful and reasonable, would diminish the yield on the excise taxes. But firstly, the realm is not made for excise taxes, excise taxes are made for the realm; they are properly speaking a resource for meeting its needs. If, however, by whatever cause it may be, they become harmful to the state, there is no doubt they must be rectified or other less ruinous measures sought—somewhat as we change or discontinue a remedy when it becomes harmful to the sick person.

Moreover, the proposed regulations should not alarm royal budget officials for the very good reason that what is not consumed in the taverns will be consumed even more—and more universally—in private homes, though ordinarily without excess and without waste of time; whereas the taverns, always open, disrupt our workers so much that one cannot usually count on them or see the end of a work once begun. We complain constantly about the harshness of the weather; why don't we rather complain about our imprudence, which leads us to make and to tolerate countless expenses and waste? [Faiguet, "Savings," vol. 5 (1755).]

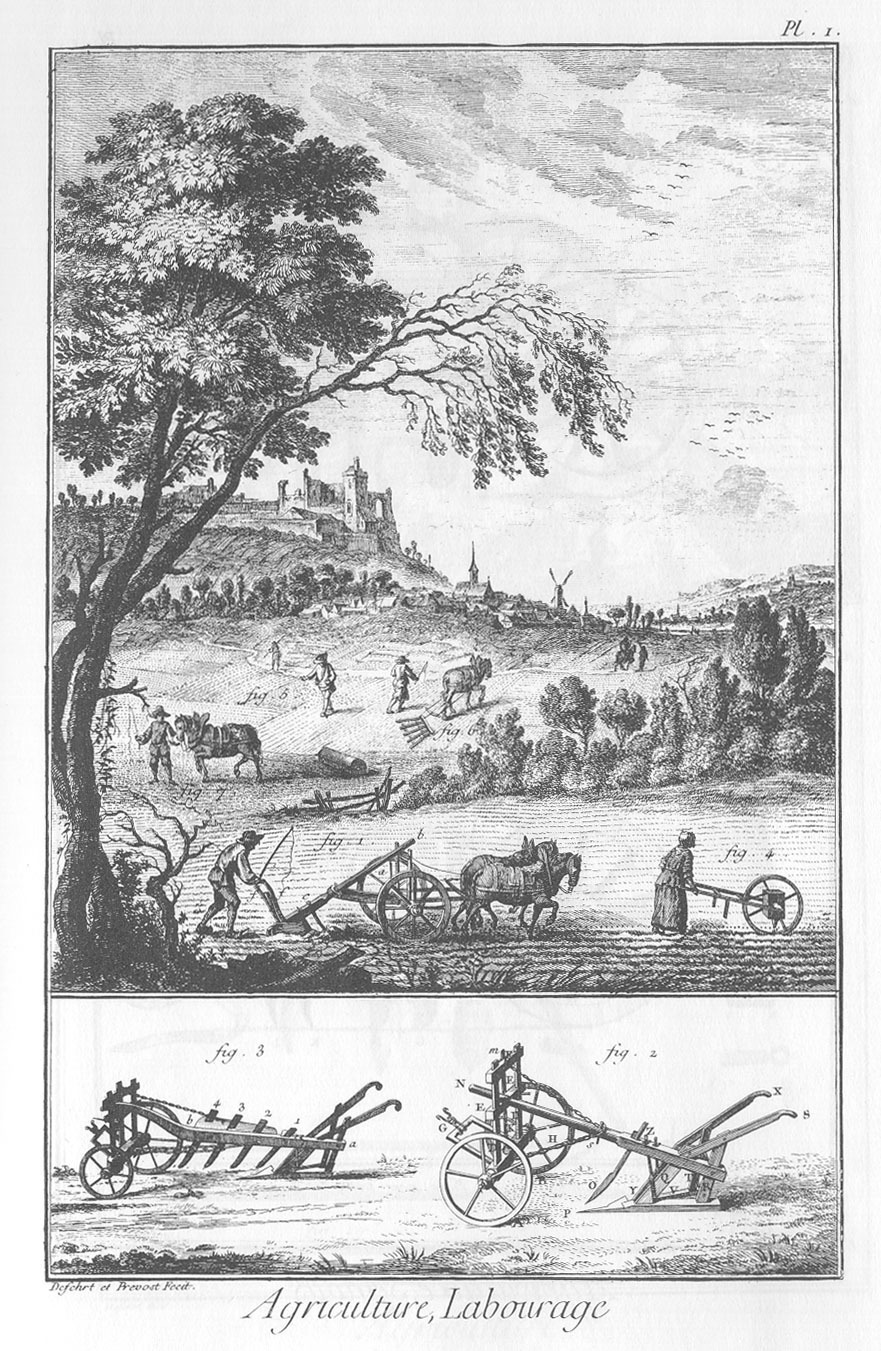

Agriculture and the Rural Economy – Plowing

Source: "Agriculture and rural economy – Plowing." The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2010. Web. <http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0001.329>. Trans. of "Agriculture et économie rustique – Labourage," Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 1 (plates). Paris, 1762.

Note: The top panel shows several people working in the fields, sowing (one is a woman), harrowing, and ploughing. Note the castle on the hill overlooking the fields, and a town with a church and windmill to grind the corn in the background. A man on horseback may be supervising their activities. In the bottom panel there is the "Tull" plough (left) and an ordinary plough (right).

Quote from Encyclopedic Liberty:

If trade were free, France could produce an abundance of foodstuffs of first necessity that would suffice for a high level of consumption and a brisk external commerce, and that could support a large trade in manual-labor works within the realm. ...

... all commerce should be free, because it is in the merchants' interest to apply themselves to the most certain and profitable branches of external trade. It is enough for the government: to attend to the increase in property income in the realm, to not obstruct human industry, and to leave citizens with the facility and choice of expenses. To reinvigorate agriculture by the activity of commerce in the provinces where foodstuffs go unsold. To abolish prohibitions and impediments detrimental to internal trade and to reciprocal external trade. To abolish or moderate excessive river and transit tolls, which destroy the income of distant provinces, where foodstuffs can be traded only after long transport. Those who own these tolls will be sufficiently compensated by their part in the general increase in the propertied income of the realm. It is no less necessary to extinguish the privileges usurped by provinces, cities, or communities for their particular advantage. It is also important everywhere to facilitate the communication and transportation of merchandise by the repair of roads and the navigation of rivers. Again, it is essential not to subject the commerce of provincial foodstuffs to prohibitions and transitory or arbitrary permissions, which ruin the countryside on the captious pretext of assuring abundance in the cities. The cities survive on the expenditures of the proprietors who inhabit them. Thus, destroying real-estate income neither encourages the cities nor procures the good of the State. [Article by Quesnay, "Cereals," vol. 7 (1757).]

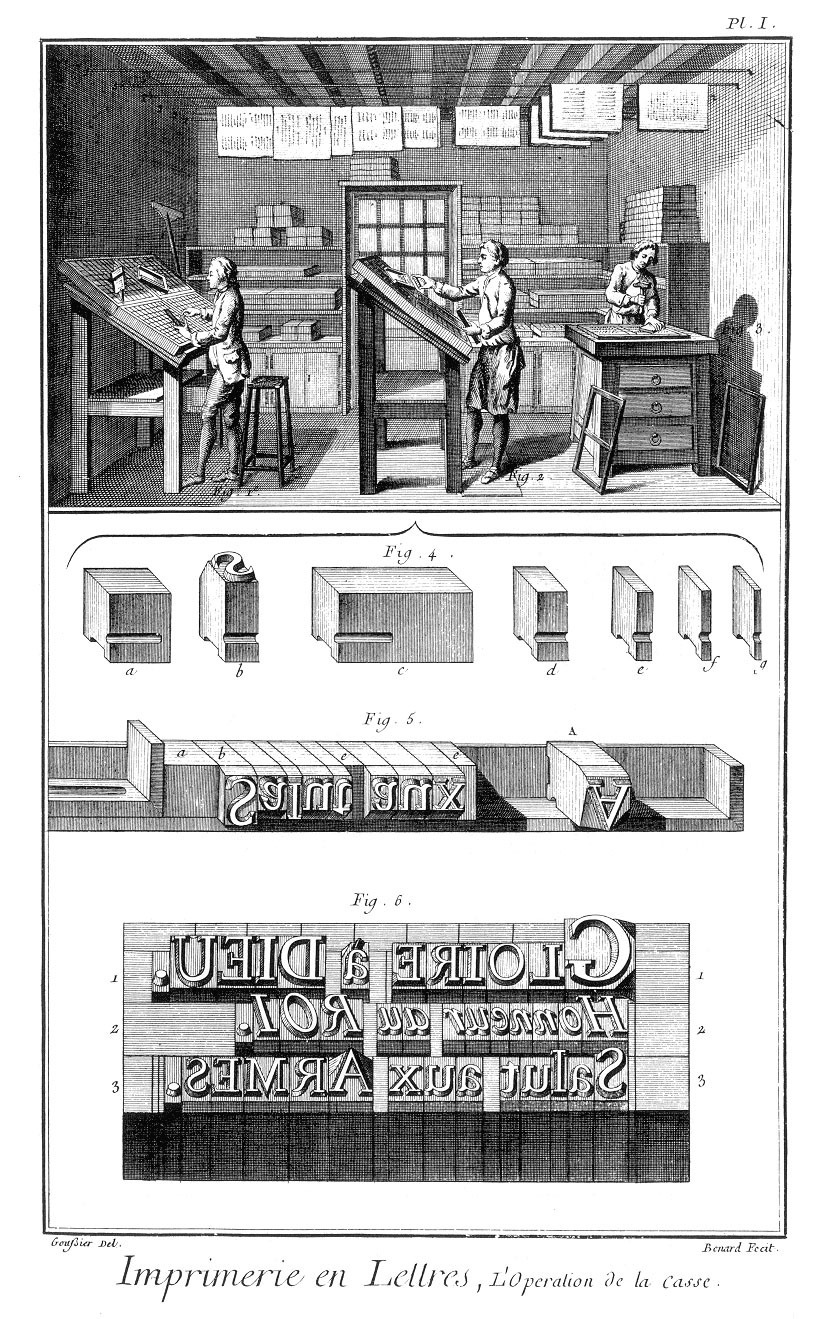

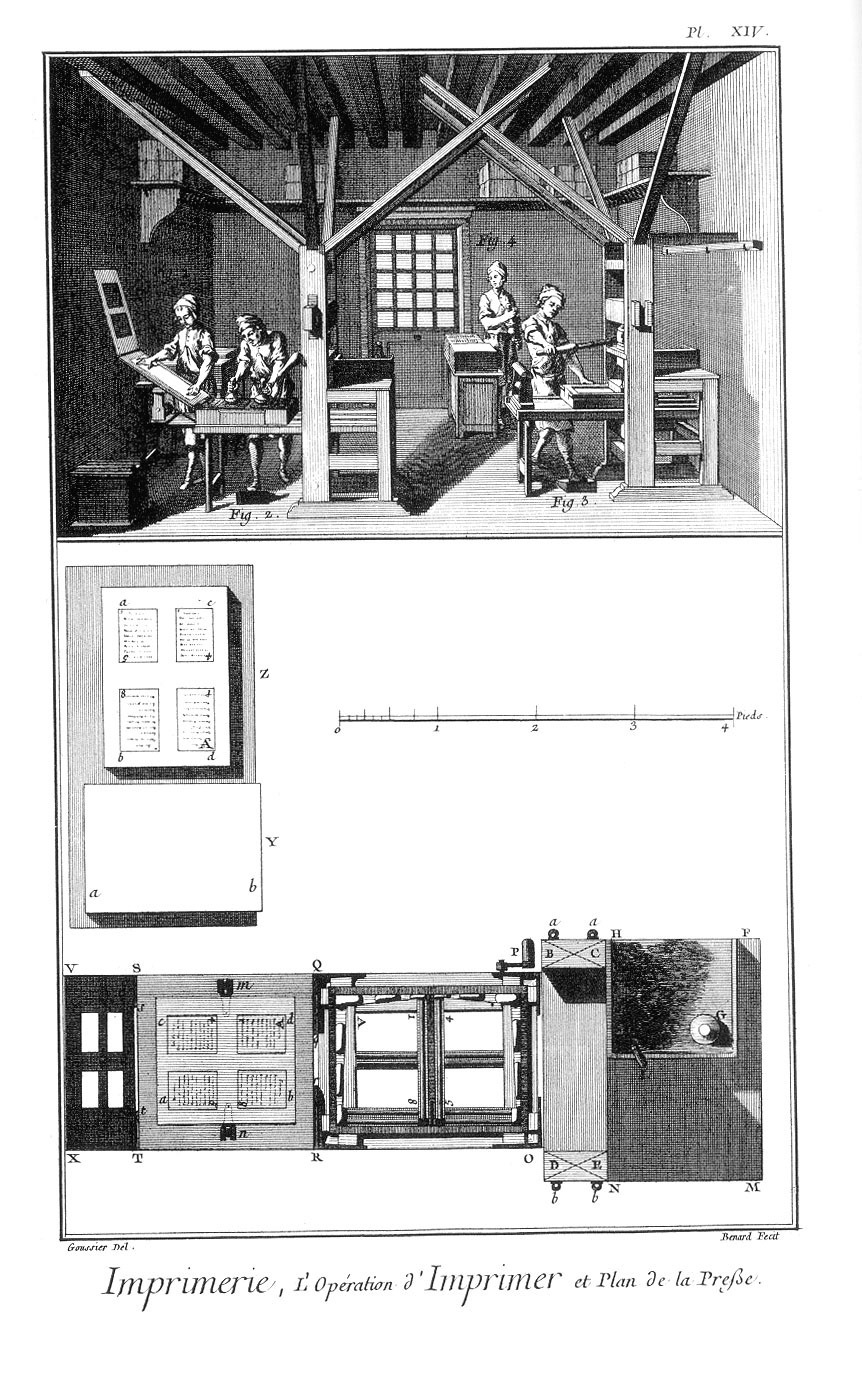

Printing

Source: "Letterpress printing." The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Translated by IML Donaldson. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2011. Web. <http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0001.562>. Trans. of "Imprimerie en caractères," Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 7 (plates). Paris, 1769.

Note: It seemed appropriate to include an illustration of printers at work since the Encyclopedia project was one of the great printing efforts of the 18th century, consisting of 17 volumes of text and 11 volumes of plates which were published between 1751 and 1772. This image show compositors setting type, the boxes containing all the pieces of type they needed to print the pages, and the wet printed pages hanging up to dry above their heads. The bottom panel shows some type which has been set (in reverse). It says "Gloire à dieu. Honneur au roi. Salut aux armes." (Glory to God. Honour to the King. Safety for the Armed Forces.)

Quote from Encyclopedic Liberty:

It is asked whether liberty of the press is advantageous or detrimental to a state. The response is not difficult. It is of the greatest importance to preserve this practice in all states founded on liberty. I say more: the drawbacks of this liberty are so trivial compared with its advantages that it ought to be the common right of the world, and that it is proper to authorize it under all governments.

We should not be apprehensive that freedom of the press will cause the harmful consequences that followed the harangues of the Athenians or the tribunes of Rome. A man reads a book or a satire in his office all alone and very coolly. It is not to be feared that he will contract the passions and the enthusiasm of another, or that he will be drawn outside himself by vehement ranting. Even if he were to take on a disposition to revolt, he never has occasions at hand to make his sentiments burst forth. Whatever abuses may be made of it, liberty of the press cannot excite popular tumults. As for the murmurs and secret discontents it may generate, isn't it better that, bursting forth only in words, it warns the magistrates in time to remedy them? It must be admitted that the public everywhere has a great disposition to believe whatever is reported that is unfavorable toward those who govern. But this disposition is the same in countries of liberty and countries of servitude. Word of mouth can spread as fast and produce as big effects as a pamphlet can. This word of mouth itself can be equally pernicious in countries where people are not accustomed to think out loud and to distinguish the true from the false, and yet one should not be troubled by such speech.

Finally, nothing can so multiply sedition and defamation in a country in which the government exists in an independent condition as the prohibition of unauthorized printing, or the grant of unlimited powers to someone to punish everything he doesn't like. In a free country, such concessions of power would become an attack against liberty, so that one can be assured that this liberty would be lost in Great Britain, for example, the instant that the attempts to impede the press succeeded. Thus, they wouldn't think of establishing that kind of inquisition. [Jaucourt, "Press," vol. 13 (1765).]

Plate XIV: Letterpress Printing, Operation of Printing and Printing Press

Note: The interior of the press room. Top left, one worker is laying a piece of white paper in a frame while a second inks the plate. To the right, another worker is using the press to ink the paper. Braces above the machine hold it in place and prevent it moving so the printed letters are as clear as possible. Below is a bird's eye view of the press machine.

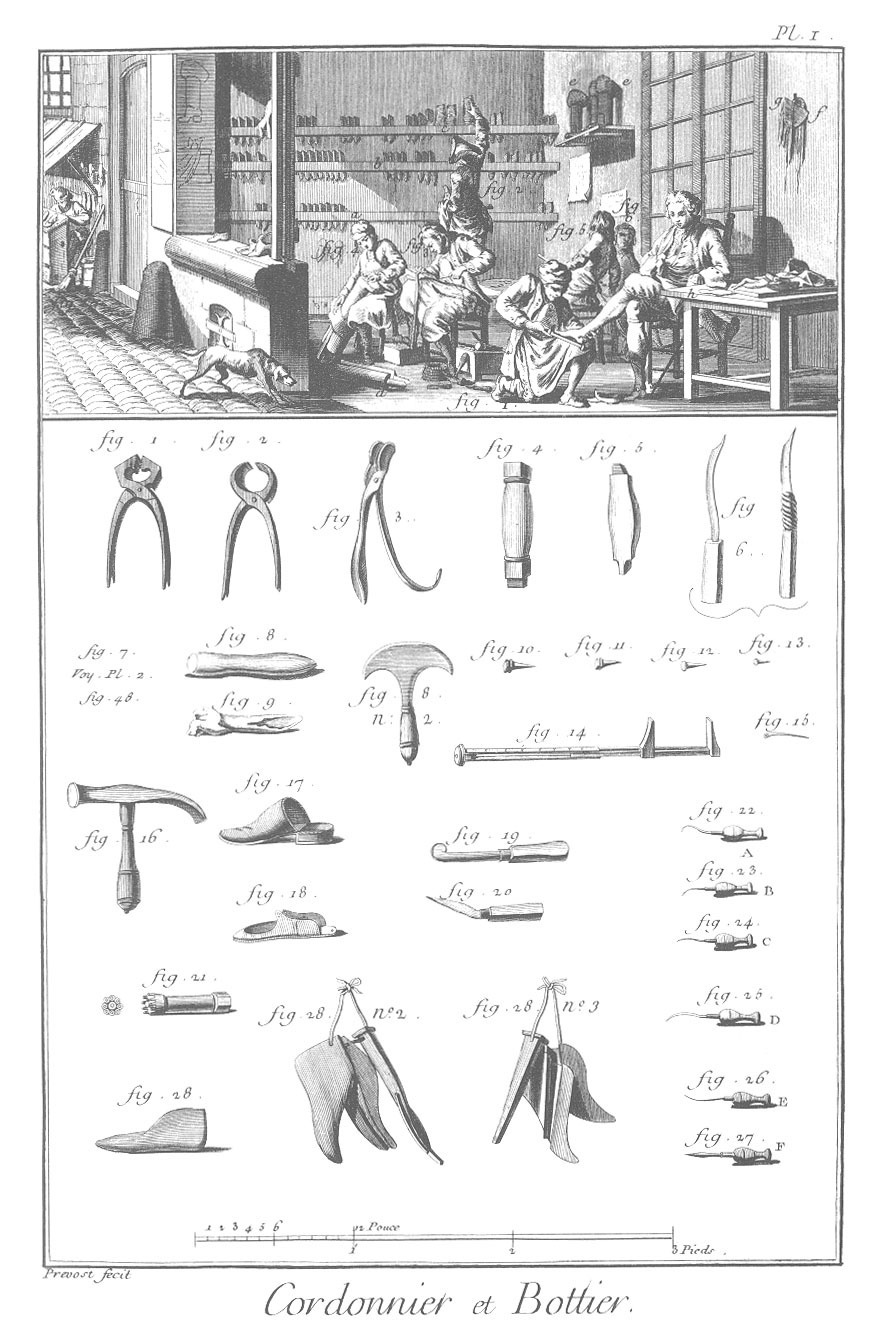

Shoe and Boot making

Source: "Shoe and boot making." The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Translated by D. A. Saguto. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2010. Web. <http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0001.431>. Trans. of "Cordonnier et cordonnier-bottier," Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 3 (plates). Paris, 1763.

Note: A cobbler's shop with several men at work making shoes and arranging them for display. What is unusual in this image is the presence of a customer being fitted for a new pair of shoes. Note also the presence of another dog sniffing about the entrance to the shop. Perhaps it can smell the animal leather.

Quote from Encyclopedic Liberty:

[On taxes on consumer goods (like shoes).] Thus, the endless multiplication of taxes on all persons and all things has done nothing but uselessly multiply the tax farms, the collections, and all the instruments of the ruin, desolation, and slavery of the people.

What, then, has made the best minds think that the duties on consumption, from which this disastrous diversity infallibly arises, are the least onerous for the subjects and the most suitable to mild and moderate government?

Wherever these duties exist, there is a constant civil war against them: a hundred thousand citizens, armed for the preservation of these duties and for the prevention of fraud on their account, constantly threaten the liberty, security, honor, and fortune of the rest.

A nobleman living in the provinces has retreated to his home; he thinks he is at peace in the midst of his family. Thirty men, with bayonet at rifle's end, surround his house, violate its asylum, scour it from top to bottom, and forcibly penetrate the most secret interior. The tearful children ask their father what crime he is guilty of; he has committed none. This attack on rights respected by the most barbarous nations is committed by these disturbers of the public peace to ensure that the home of this citizen holds no merchandise of a kind whose exclusive sale the tax farmer has reserved for himself—in order to resell it at a profit of seventeen or eighteen times its value.

This is not rhetoric, this is fact. If this is enjoying civil liberty, I would like someone to tell me what servitude is. If this is how persons and property have security, what does it mean not to have it?

It will be only a matter of luck if these police hunters, who have an interest in finding guilty parties, do not themselves create some, bringing into your home what they came to look for. For then your ruin is assured, and it is in their hands. Unique procedures, convictions, fines, and all the methods that the cruelest vexations can muster are authorized against you.

I would prefer to dissimulate the even greater and more shameful evils of which these taxes are the source. The enormous disparity between a thing's price and the duty on it renders fraud highly lucrative and invites men to engage in it. People who could not possibly be regarded as criminals lose their lives for attempting to preserve their lives. But the tax farmer, whose interest repulses all remorse, pursues from the comfort of his murderous opulence all the rigor of punishments inflicted by the law upon the wicked against those whom his own illegitimate gains have often reduced to the cruel necessity of exposing themselves to such punishments. I do not like it, said Cicero, that a people dominating the world should at the same time be its agent. There is something more distressing than what displeased Cicero.

I know that not all duties on consumption expose citizens to such terrible dangers. But all are equally contrary to their liberty, their security, and all natural and civil rights, because of the surveillances, the inquisitions, and the searches—as oppressive as they are ridiculous—that they occasion. They even bring the misfortune of constricting the sentiments of humanity itself. [Damilaville (Diderot), "Five Percent Tax (Vingtième)," vol. 17 (1765).]

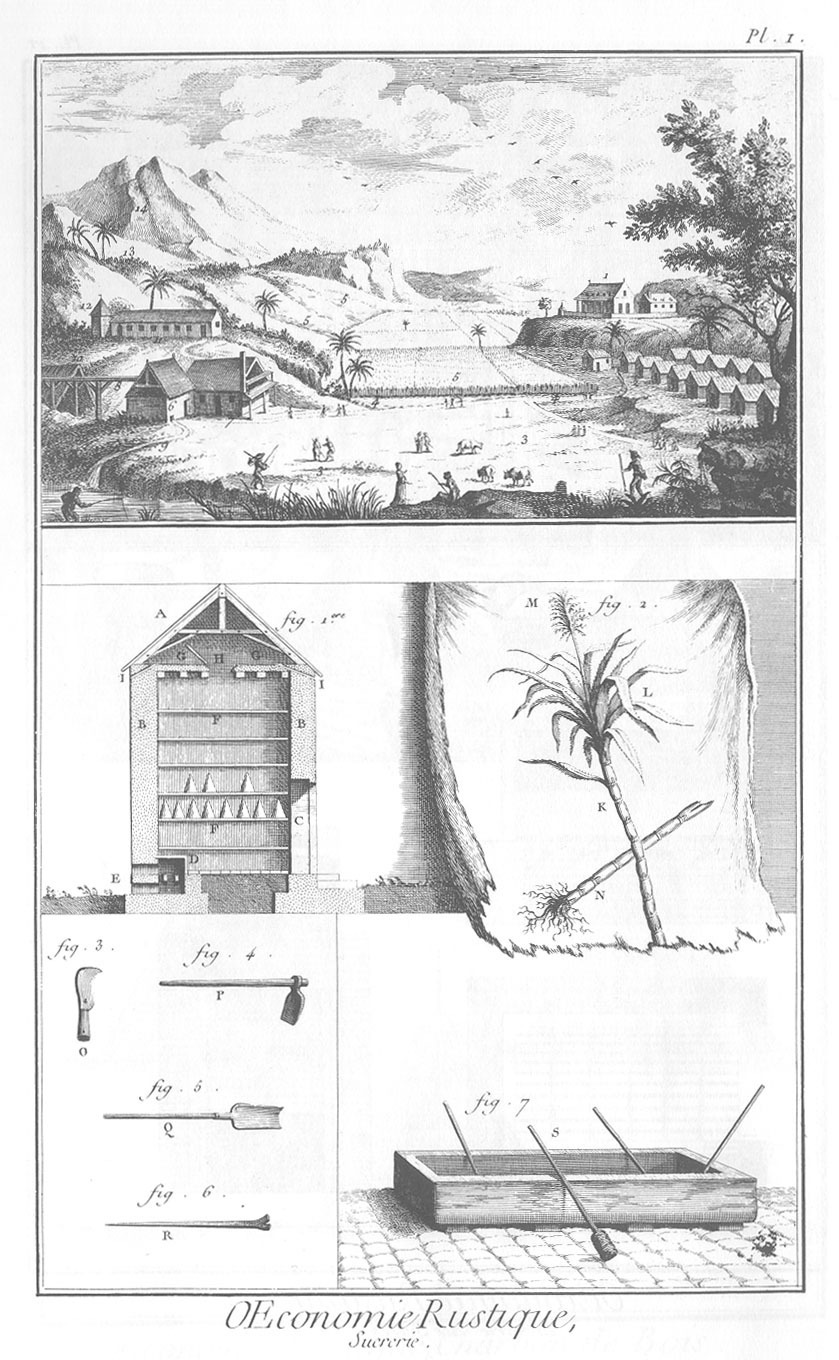

Sugar Plantation and Refining

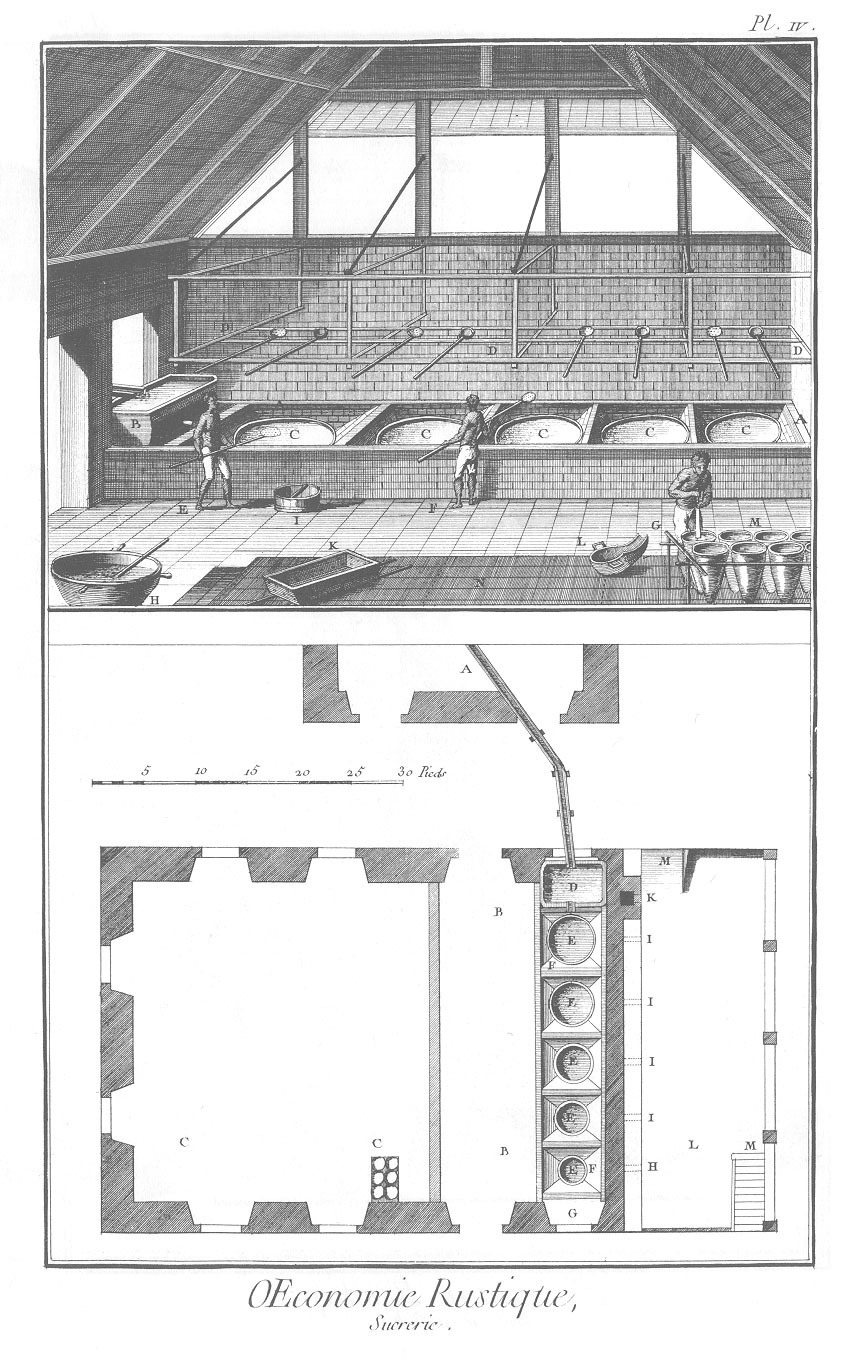

Plate I: Rural Economy, Sugar Plantation

Source: "Agriculture and rural economy – Sugar plantation and refining." The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2010. Web. <http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0001.344>. Trans. of "Agriculture et économie rustique – Sucrerie et affinage des sucres," Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 1 (plates). Paris, 1762.

Note: The top panel shows a sugar plantation of the French colony of the Antilles. To the right on the hill is the mansion of the slave owner, below which are rows of slave quarters. In the foreground are slaves going about their business in the fields. At the lower left there is a water mill. Note the figures along the bottom of the panel. They seem to be Europeans who are engaged in various leisure activities such as fishing, sitting and talking (one is a women), or walking, i.e. not working.

Quote from Encyclopedic Liberty:

Slavery is the establishment of a right founded on force. This right makes a man belong to another man so much that the latter is the absolute master of his life, his goods, and his liberty. …

The law of the strongest, the right of war harmful to nature, ambition, the thirst for conquest, the love of domination and of indolence—these introduced slavery, which, to the shame of humanity, has been accepted by virtually all the world's peoples. In fact, we cannot cast our eyes over sacred history without discovering the horrors of servitude. Profane history—the history of the Greeks, the Romans, and all other peoples that pass for the most civilized—are so many monuments to that ancient injustice engaged in with more or less violence over the whole face of the earth, varying with the times, places, and nations. …

But when they had aggrandized themselves by their conquests and their plunder, when their slaves were no longer the companions of their labor but were employed to become the instruments of their luxury and their pride, the slaves' condition totally changed its face. They came to be regarded as the basest part of the nation, and consequently no one had any scruples about treating them inhumanely. By reason of the fact that mores were gone, men had recourse to the law. And indeed, some terrible ones were needed to establish the security of these cruel masters, who lived amidst their slaves as if amidst their enemies. …

After surveying the history of slavery from its origins to our day, we are going to prove that it wounds the liberty of man, that it is contrary to natural and civil right, that it is offensive to the best forms of government, and finally, that it is useless in itself. …

Moreover, in every government and in every country, however arduous the work that society requires, one can do anything with free men—by encouraging them with rewards and privileges, by adjusting the work to their strength, or by replacing it with machines invented and applied by art, depending on location and need. …

Thus, it goes directly against nature and the law of nations to believe that the Christian religion gives those who profess it a right to reduce to servitude those who do not profess it, in order to work more easily toward its propagation. It was this way of thinking, however, that encouraged the destroyers of America in their crimes, and this is not the only time that men have used the religion against its own maxims, which teach us that the status of (loving thy) neighbor extends throughout the world. …

Let us conclude that slavery—founded by force, by violence, and in certain climates by an excess of servitude—can perpetuate itself in the world only by the same means. [Jaucourt, "Slavery," vol. 5 (1755).]

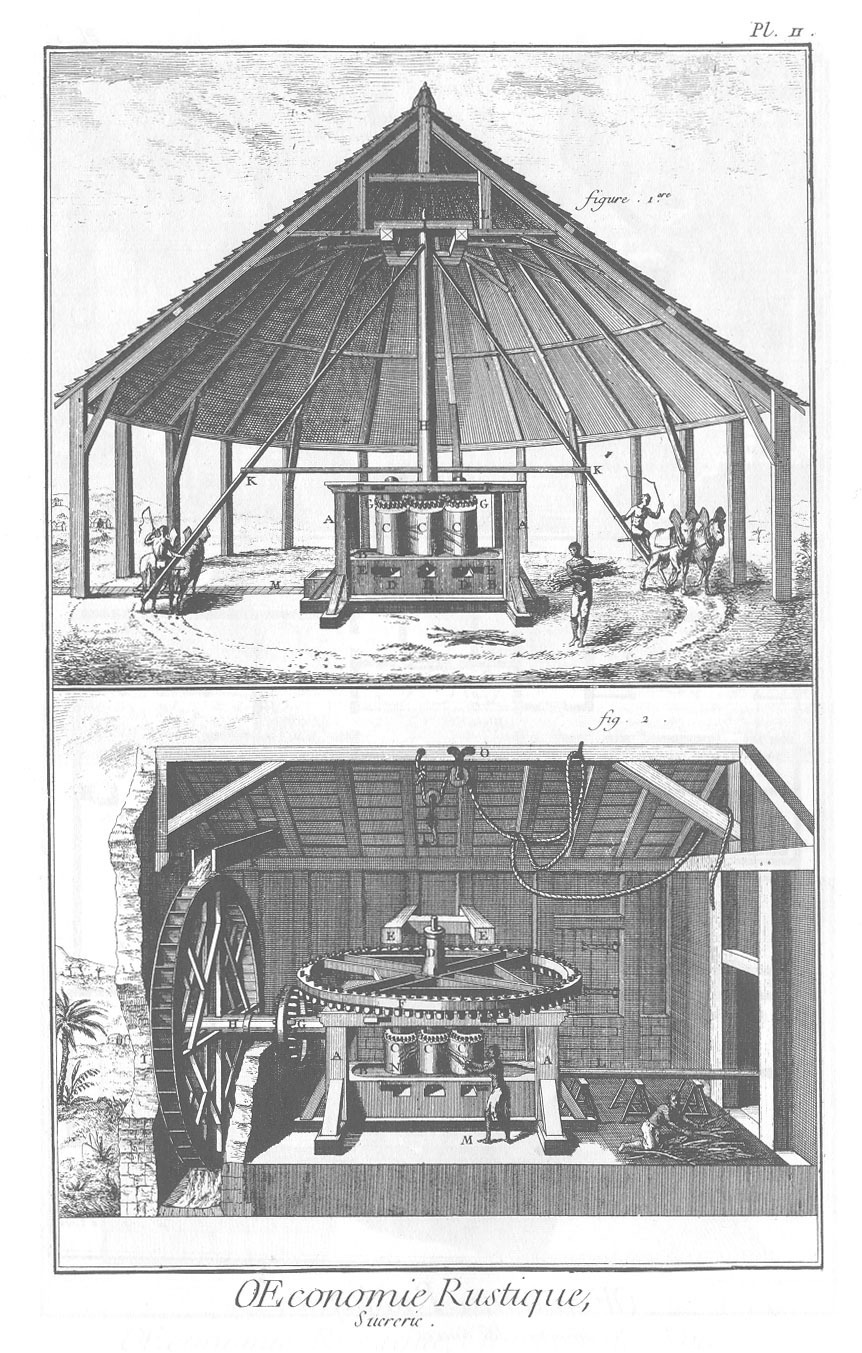

Plate II: Rural Economy, Sugar Plantation

Note: These panels show two different types of mills used to crush the juice out of the sugar cane. The top one is driven by horses, the bottom one by water power. In both cases, slaves are feeding the raw sugar cane into the presses. This was dangerous work as they could get their hands caught in the machinery.

Plate IV: Rural Economy, Sugar Plantation

Note: A sugar refinery where large cauldrons of sweet syrup are heated to evaporate the water and make the concentrate. Near naked slaves are working in a very hot and dangerous environment. We cannot see the fires below which gave out a great deal of heat and smoke.

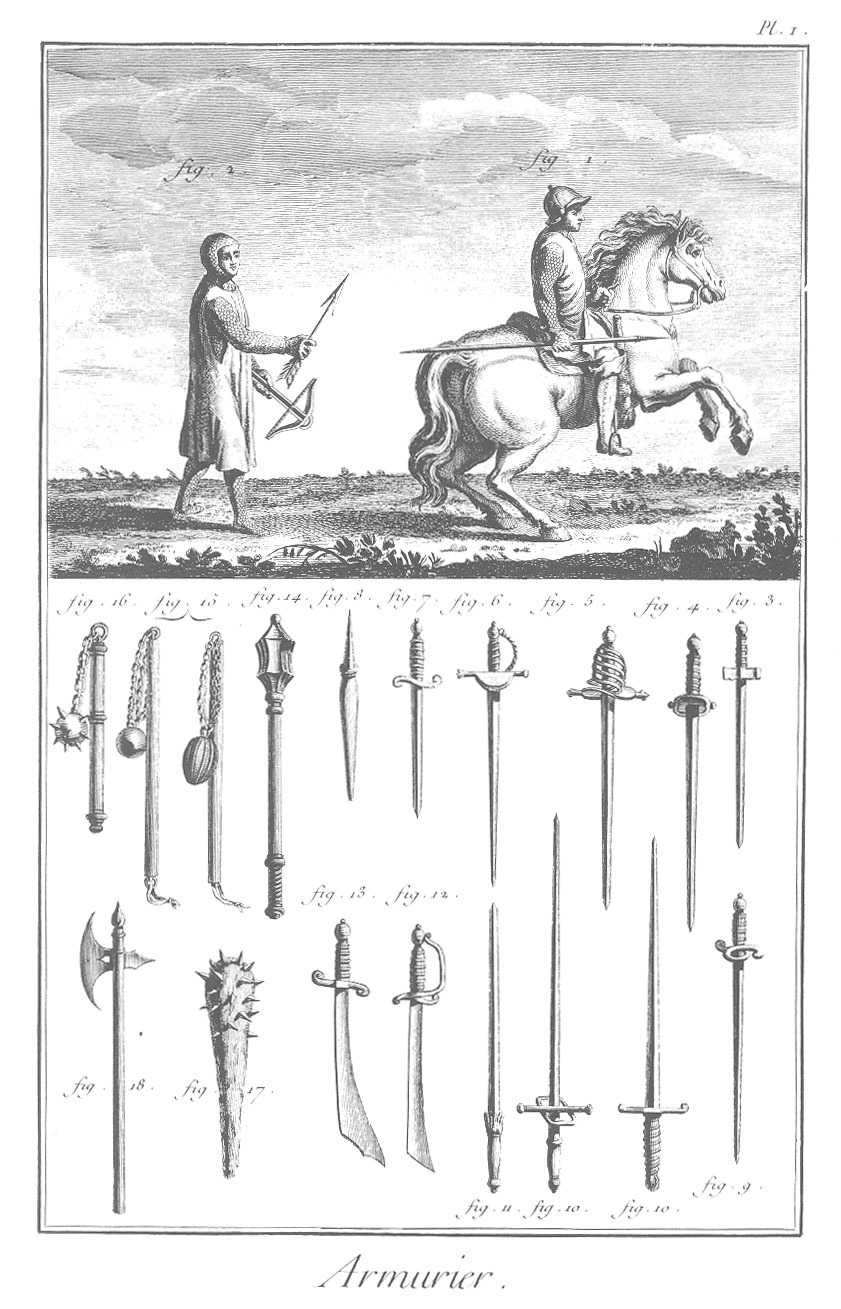

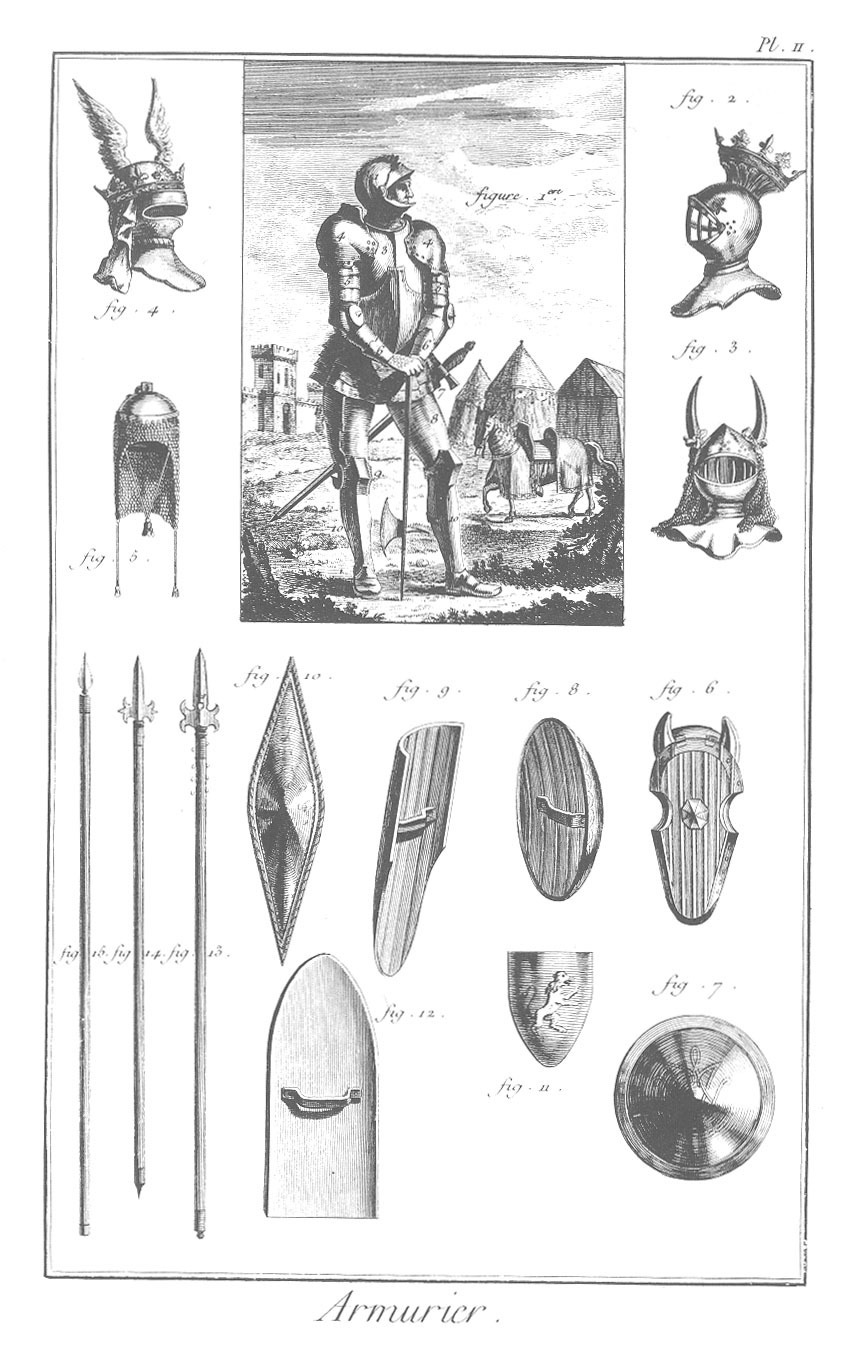

Armeror: Sword making and Armour

Plate I: Gunsmith - Arms of the Ancient French

Source: "Gunsmith." The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2010. Web. <http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0001.377>. Trans. of "Armurier," Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 1 (plates). Paris, 1762.

Note: The title is given as "The armour of the ancient French" which means here medieval. There are references to King Louis XI, and the warriors Roland and Olivier who fought when Charlemagne ruled France. Since so much of the Encyclopedia was devoted to explaining modern science and technology to have images like this one would have shocked the reader because it would remind them of the world the Encyclopedists wanted to leave behind.

Quote from Encyclopedic Liberty:

Those armies were composed of citizens who cost the state nothing, or very little. They were married; they had assets in the republic and returned home after the war. Our armies are standing armies, even in peacetime; their maintenance incurs surcharge taxes, which reduce the people who support them to a state of wretchedness, and thus remove them from conditions that favor propagation. They are composed of mercenaries, whose only asset is their soldier's pay; they are prevented from marrying, and that is reasonable. Who would feed their wives and children? Their pay is not enough for their own survival; they are a multitude of bachelors that perpetually exist, that do not reproduce, that must continually be renewed with more bachelors that are removed from the reproducing population; it is a monstrous form of anthropophagy that devours a portion of the human species in each generation. We must agree that we have some strange opinions and contradictions; we think it is barbarous to mutilate men in order to make singers of them, and that is right; however, we do not think it so to castrate men in order to make homicides of them.

It is the desire to dominate; it is ostentation, luxury, and vanity, more than the security of states, that caused the introduction into Europe of the custom of preserving even in peacetime these multitudes of armed men who are useless, who ruin peoples, and who also exhaust the powers that maintain them of their men and wealth. The more people there are to command, the more titles there are; the more titles there are, the more dependents and courtiers there are to obtain them. No power has made gains in its security through the increase in costs that it has caused for itself. All of them have increased their troops in proportion to the troops their neighbors have kept on active duty. The armed forces are all at the same level, as they were before; the state that was protected with fifty thousand men is not better protected with 200,000 today, because the forces against which they sought to protect themselves were increased to the same level. The advantages of greater security, which were the excuse for this increased expenditure, are thus reduced to zero; only the expenditure and the depopulation remain.

Nothing compensates society for these expenditures; while Europe is quiet, the troops are held in a state of inaction that is deadly for them once war erupts. Being unused to working, they become enervated, and the least fatigue to which they are later subjected destroys them. [Article by Damilaville, "Population," vol. 13 (1765).]

Plate II: Gunsmith

Note: See the note above. The notes says this suit of armor comes from the 15th century and that some of the images of faces were taken from medallions which showed Charles VII and Philippe the Good. In the background we can see a castle, some tents, and a knight's horse.

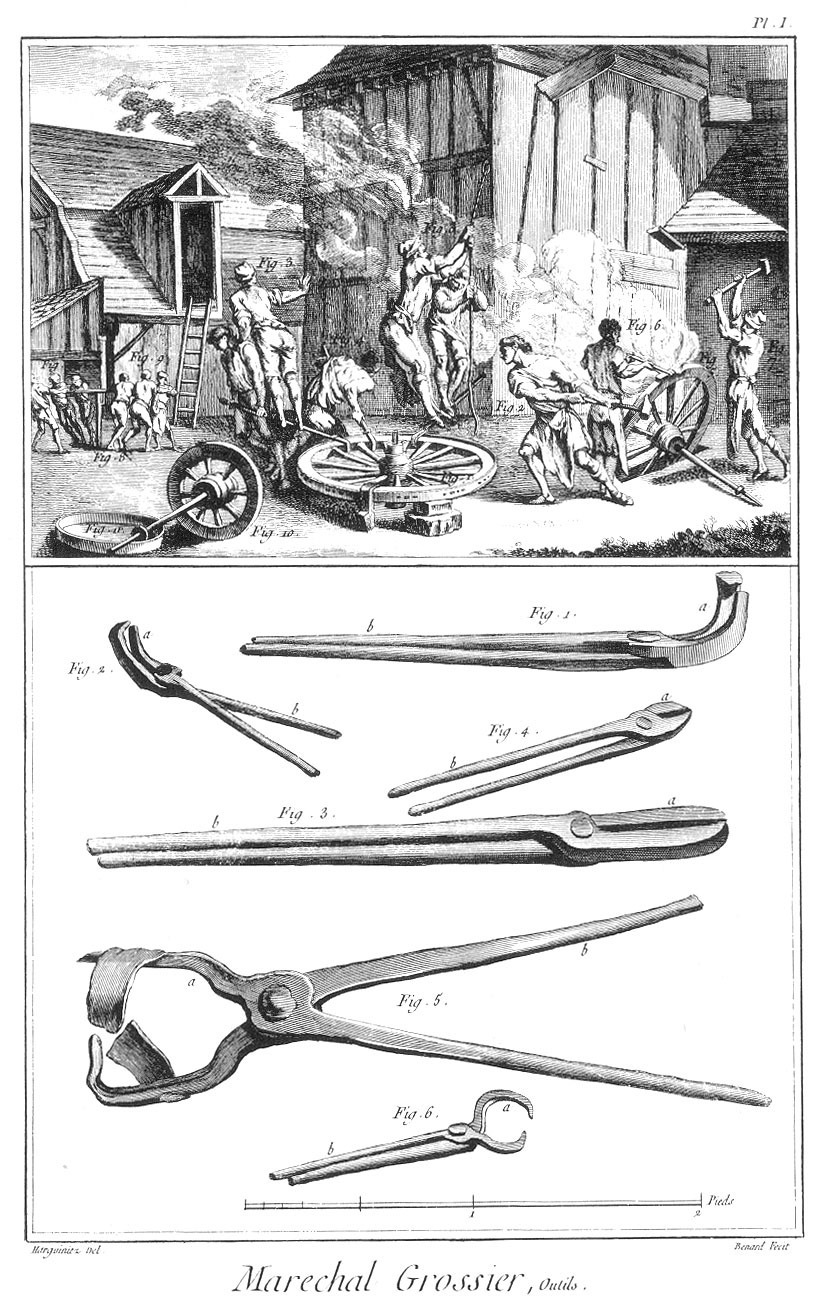

Wheelwright

Plate I: Wheelwright, Tools

Source: "Wheelwright." The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Translated by E. Clair Guy. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2010. Web. <http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0001.566>. Trans. of "Maréchal grossier," Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 7 (plates). Paris, 1769.

Note: Wheelwrights at work attaching metal rims to wagon wheels. On the left we see men straining to remove a wheel nut. In the centre men are standing on levers in order to force the metal rim over the wooden wheel as a colleague to the right hits the rim with a hammer. On the right a worker is holding a rim with a pair of pliers while another hits it with a hammer perhaps shaping the metal while it was still hot. This rim seems to be very hot as smoke or steam is being emitted.

Quote from Encyclopedic Liberty:

[On deregulating the guilds or corporations which controlled craftsmen and their trades.] People think that masterships and preferential initiations were established to certify the competence required in those who practice commerce and the arts, and even more to foster emulation, order, and equity among them. But in truth, they are merely refinements on monopoly that are truly harmful to the national interest—besides which, they have no necessary connection with the wise arrangements that ought to guide the commerce of a great people. We will even show that nothing contributes more to fortify ignorance, bad faith, and laziness in the various occupations. …

No one is unaware that the masterships have degenerated considerably since their original establishment. In the beginning, they consisted more in maintaining good order among the workers and merchants than in taking substantial sums from them. But since they have been turned into a tax, "they are nothing more," says Furetiere, "than cabal, drunkenness and monopoly." The richest or most powerful usually manage to exclude the weakest, and thereby draw everything to themselves—a persistent abuse that can never be eradicated except by introducing competition and liberty into each occupation. …