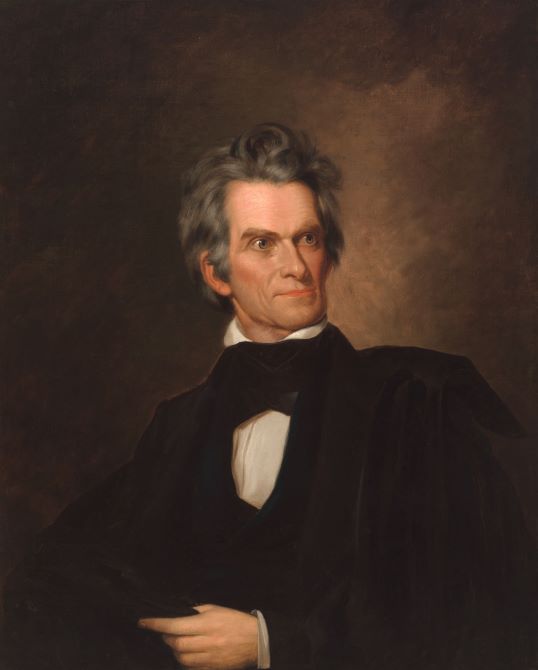

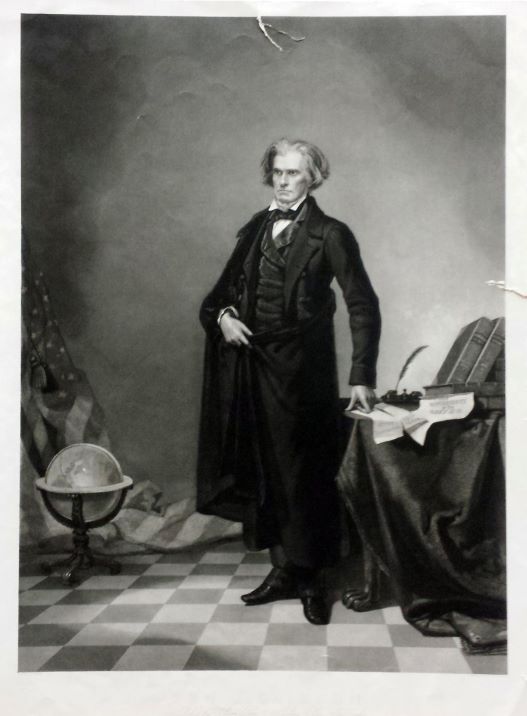

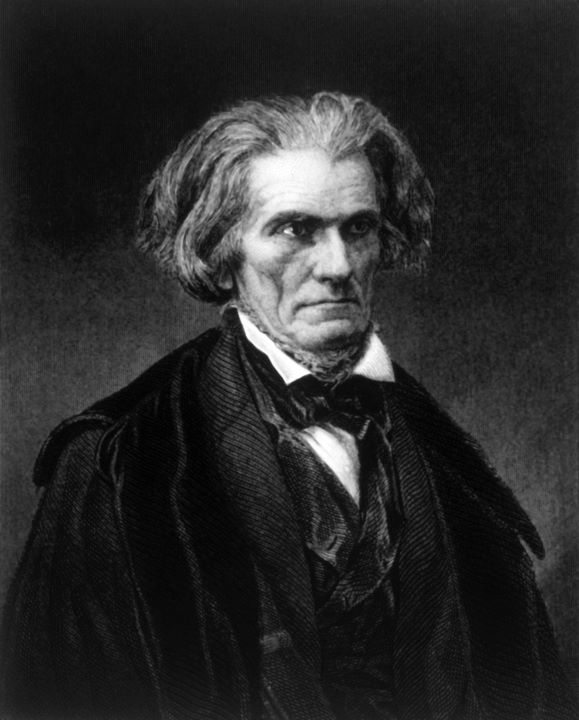

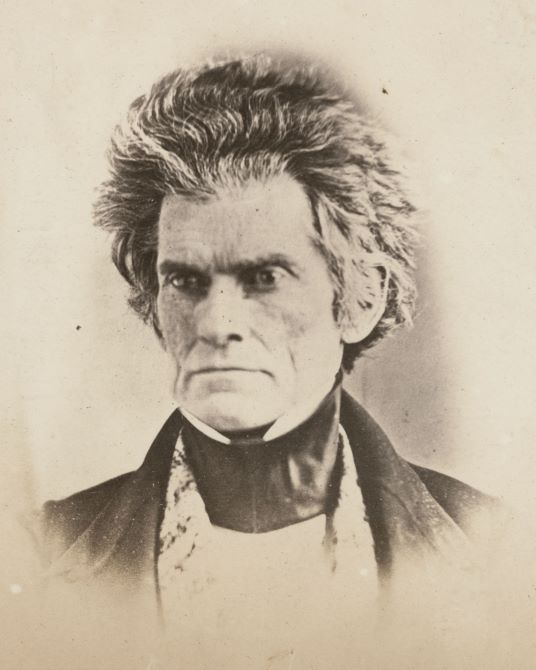

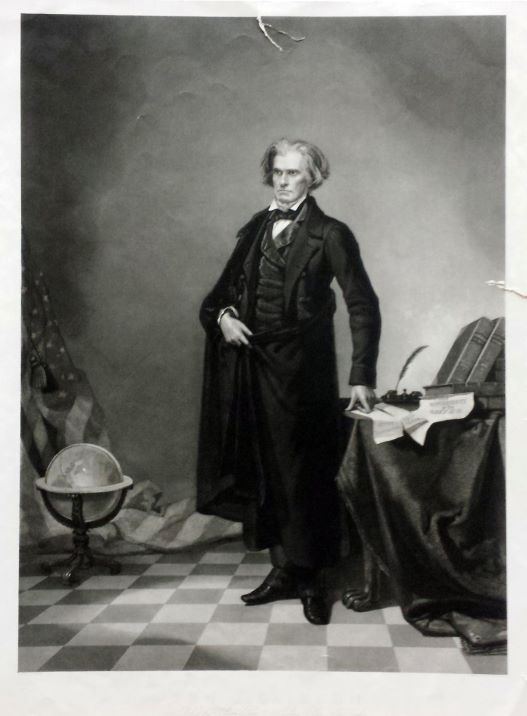

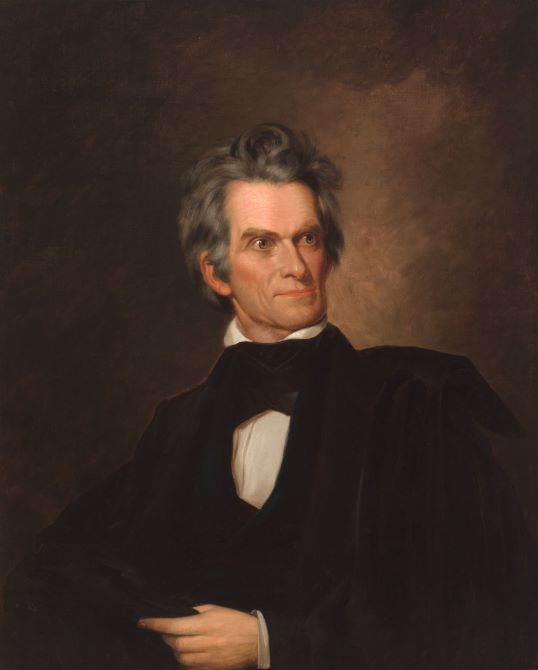

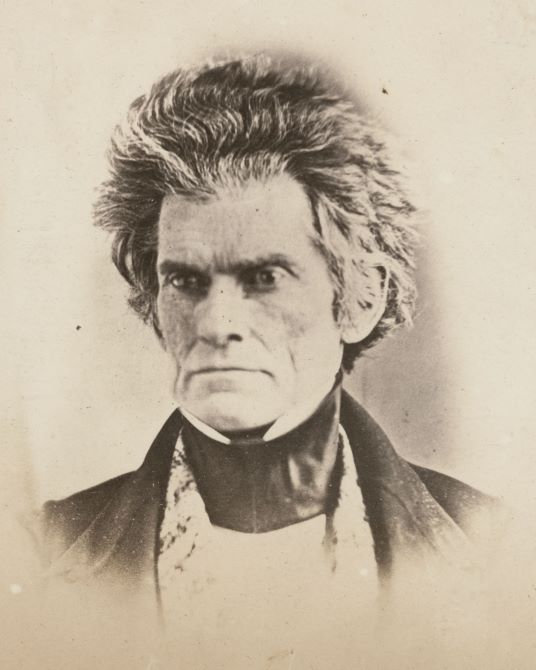

Welcome to our March 2021 edition of Liberty Matters. This month Keith Whittington has written our lead essay on John C. Calhoun. Calhoun was one of the most formidable political thinkers of his era as well as a former Vice President, a member of the House and Senate, and a Secretary of State and War during the first half of the 19th century. He was also a Southerner and a defender of the institution of slavery. As Professor Whittington notes in his essay, Calhoun is fascinating because his writings address many of the issues we are facing about the nature of our Constitutional order today. Much like America during Calhoun’s lifetime, we are deeply divided along regional lines in America today, and Calhoun’s writings on state “nullification” and concurrent majorities speak to many of the discussions we have had about our divisive political landscape. However his defense of slavery was and is so deeply at odds with America’s contemporary culture and values that re-examining Calhoun today helps us confront the question of whether or not we can still learn from the contributions of some historical figures even if we find some of their views repugnant and offensive.

Response Essay John C. Calhoun and the Merits of Minority Rights

I want to thank Liberty Fund for inviting me to participate in this forum on John C. Calhoun. I agree with Keith Whittington’s observation at the beginning of his thoughtful essay: that Calhoun is a figure of “enduring interest and controversy” because he “exemplified the contradictions of his age and in some ways of the American experience.”

I believe the contradictions Calhoun exemplified are still with us, despite the transformations wrought by the Civil War. Calhoun’s thought merits attention not only for what is perceptive in it, but also for its blind spots. Both his acuity and his blindness are relevant to our deeply polarized age.

Because I agree with most of Keith’s essay, my response is not a counterpoint, but instead extends some lines of thought initiated in the essay, and expands on some themes it treated briefly. I share Keith’s judgment that Calhoun’s analysis of the way in which democratic politics can degenerate into the selfish pursuit of narrowly partisan or sectional interests holds up better than his prescribed remedy: state nullification of federal law, and more generally, arming each “portion” or “interest” of the society with veto rights over decisions affecting all.

I also agree that it is possible, to a degree, to separate “Calhoun’s analysis of democratic constitutional politics” from “his motivation for developing such an analysis” – which was principally to defend the interests of slaveholders. Calhoun’s analysis of how a self-interested majority consolidates its power at the expense of a minority with distinctly different interests can illuminate the political dynamics of societies where slavery is not practiced at all, and where entrenched majorities and minorities, unlikely ever to alternate in power, are divided by religion, language, ethnicity, or something else other than slavery. In transplanting Calhoun’s political science to these other contexts, however, we should also ask why, for him, white slaveholders counted as a minority whose rights and interests merited protection, and black slaves did not.

Though I agree with Keith, both about the perceptiveness of Calhoun’s analysis of democratic politics, and about the unworkability of his proposed remedy, I believe it is important to ask why Calhoun believed a system of constitutionally-guaranteed mutual vetoes would lead to “compromise and consensus-building around genuine shared interests,” as Keith phrases it, rather than to gridlock, paralysis, and disunion. If an ill person persists in demanding treatments that worsen the disease, it is not enough to inform the patient that those treatments are ineffective. We might also ask why this particular disease disposes patients, including those who are intelligent and well-informed, to place their faith in counterproductive remedies.

Calhoun spoke and acted within a deeply polarized United States. It did not appear this way at the beginning of his career, when he trusted statesmen from all sections of the United States to comprehend and work for the good of the whole country. He believed that he himself, as a political leader, had done so. But increasingly divergent sectional interests, first over trade policy (pitting the protectionist interests of northern manufacturers against the free trade interests of southern planters), then even more sharply over slavery, combined with the readiness of politicians to exploit sectional divisions, led Calhoun to conclude that such gulfs could not be bridged through any decision process that left the final decision to majority vote – even if all of the regular constitutional rules were followed.

Citizens living in one region of the country, with their own regional economic interests and distinct way of life, would have little understanding of the interests and lives of fellow citizens residing thousands of miles away. (Plantation slavery in Calhoun’s view exemplified a very different mode of production than northern capitalism, a distinct way of resolving “the inevitable and revolutionary conflict between labor and capital,” as Keith notes.) If one section enjoyed a numerical majority, it would not hesitate to use the machinery of government to promote its own sectional interests even if this deeply harmed the interests of another section. Each would increasingly view the other as foreign to itself, even as enemies.

Calhoun did not believe such deep divisions could be bridged at the popular level. He did, however, believe they could be overcome by negotiation and compromise among the elected leaders of each section – but only with the right kind of decision process. Under any system that allowed a numerical majority to make the final decision, Calhoun maintained, elected representatives would simply mirror the selfish demands of their constituents, and majority tyranny in the society would be reproduced within the legislative process. Statesmen from different sections could converge on a true common good only under the constraint of a very different decision rule.

Here is where Calhoun’s constitutional doctrine of nullification enters the picture, and more generally, his theory of the concurrent majority, whereby every significant “portion” or “interest” of the society is armed with veto rights to employ at its own discretion. Calhoun believed that the urgent need for common action, combined with the fact that nothing could be accomplished unless leaders from every section consented, would produce an accommodation acceptable to all. “When something must be done – and when it can be done only by the united consent of all – the necessity of the case will force to a compromise – be the cause of that necessity what it may.”[1]

It was this genuine, but in practice deeply flawed, vision of how to realize a common good transcending all sections and interests that distinguished Calhoun from most other defenders of states’ rights and slavery. Keith observes that “Calhoun was not alone in embracing a theory of state nullification”; what distinguished him was the detail he provided about “how it would work and why it was justified.” Calhoun did not view himself as opposing protective tariffs and defending slavery simply because these were the special interests of his state and section. He saw both free trade, and the perpetuation of slavery, as good for the entire United States. His theory thus gave slaveholders a good conscience about their uncompromising defense of slavery.

Calhoun insisted that states had an unquestionable right of secession. Yet he viewed the prospect of secession with dread. He believed that nullification, and the threat of secession, by forcing Northerners to recognize the error of their ways, would make actual resort to secession unnecessary and thereby preserve the Union to the benefit of all.

This was one of his blindnesses. But I not believe this particular blind spot was limited to Calhoun, or to the issue of slavery. Instead I would suggest that deep and long-lasting political polarization (which we also experience today) generates the fear that, if the party or group to which one belongs loses even one political contest, all is lost forever. In this frame of mind, one may resort to extreme measures to forestall any loss of power. Nullification is one such extreme measure. There are others.

Calhoun’s greatest blindness was slavery, which he insisted was a positive good. This placed him “at odds with core American tenets,” as Keith observes, and led him to renounce “the principles that Americans had long taken as commonplace and that Abraham Lincoln took as those upon which the nation was conceived and dedicated.”

But a “commonplace” can refer to something voiced without active thought. Calhoun knew that the signers of the Declaration, and many though not all who signed the Constitution, spoke of slavery as wrong in principle. But he suspected that many did not deeply believe this; actions spoke louder than words. Calhoun argued that delegates to the Federal Convention of 1787, including Northerners, by affirming the final document had accepted “the most solemn obligations, moral and religious” to protect and defend the institution of slavery.[2]

Moreover, Calhoun judged that his fellow slaveholders were mouthing empty platitudes. When Calhoun proclaimed in the Senate in 1837 that slavery was not an evil at all but “a good – a great good,” Senator William Cabell Rives of Virginia, a slaveholder, reaffirmed the commonplace that slavery was “a misfortune and an evil in all circumstances, though in some, it might be the lesser evil.” Calhoun replied that if Rives considered slavery an evil, then “as a wise and virtuous man” he “was bound to exert himself to put it down.”[3] In short: you don’t believe your own words.

What we today, echoing Lincoln, regard as America’s settled principles were in 1850, when Calhoun died, anything but settled. It was not predetermined that Lincoln’s republican vision would triumph over Calhoun’s. Nor do I believe that Lincoln’s version is beyond reversal today -- though if reversed, what would take its place would horrify Calhoun as well as Lincoln.

Endnotes

[1] Calhoun, A Disquisition on Government, in Ross M. Lence, ed., Union and Liberty: The Political Philosophy of John C. Calhoun (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1992), 49. [2] Calhoun, “Resolutions on Abolition and the Union,” December 27, 1837. In Clyde N, Wilson, ed., The Papers of John C. Calhoun, Vol. XIV (Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press, 1981), 32.

[3] Calhoun, “Speech on the Reception of Abolition Petitions,” February 6, 1837. Lence, ed., Union and Liberty, 467-468.

[3] Calhoun, “Speech on the Reception of Abolition Petitions,” February 6, 1837. Lence, ed., Union and Liberty, 467-468.