1776: Declaration of Independence (various drafts)

Source:A chapter in Becker's The Declaration of Independence: A Study on the History of Political Ideas (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co., 1922).

CHAPTER IV. DRAFTING THE DECLARATION

The committee appointed June 11, 1776, to prepare a declaration of independence consisted of Jefferson, Adams, Franklin, Sherman, and Robert R. Livingston. In his Autobiography,1 written in 1805, and again in a letter to Pickering, written in 1822, Adams says that the Committee of Five decided upon “the articles of which the declaration was to consist,” and it then appointed Jefferson and himself a subcommittee to “draw them up in form.” When the sub-committee met, he says,

Jefferson proposed to me to make the draught, I said I will not; You shall do it. Oh no! Why will you not? You ought to do it. I will not. Why? Reasons enough. What can be your reasons? Reason 1st. You are a Virginian and a Virginian ought to appear at the head of this business. Reason 2nd. I am obnoxious, suspected and unpopular; you are very much otherwise. Reason 3rd. You can write ten times better than I can. ‘Well,’ said Jefferson, ‘if you are decided I will do as well as I can.’ Very well, when you have drawn it up we will have a meeting.2

Jefferson’s account is different. Writing to Madison in 1823, he says:

Mr. Adams memory has led him into unquestionable error. At the age of 88 and 47 years after the transactions,….this is not wonderful. Nor should I….venture to oppose my memory to his, were it not supported by written notes, taken by myself at the moment and on the spot…. The Committee of 5 met, no such thing as a sub-committee was proposed, but they unanimously pressed on myself alone to undertake the draught. I consented; I drew it; but before I reported it to the committee I communicated it separately to Dr. Franklin and Mr. Adams requesting their corrections;….and you have seen the original paper now in my hands, with the corrections of Dr. Franklin and Mr. Adams interlined in their own handwriting. Their alterations were two or three only, and merely verbal. I then wrote a fair copy, reported it to the committee, and from them, unaltered to the Congress.1

This ‘original paper’ of which Jefferson speaks, ‘with the corrections of Dr. Franklin and Mr. Adams interlined in their own handwriting,’ is commonly known as the Rough Draft. It has been preserved, and may now be seen in the Library of Congress in Washington, or, in excellent facsimile, in Mr. Hazelton’s indispensable work on the Declaration of Independence.1 A more interesting paper, for those who are curious about such things, is scarcely to be found in the literature of American history. But the inquiring student, coming to it for the first time, would be astonished, perhaps disappointed, if he expected to find in it nothing more than the ‘original paper….with the corrections of Dr. Franklin and Mr. Adams interlined in their own handwriting.’ He would find, for example, on the first page alone nineteen corrections, additions, or erasures besides those in the handwriting of Adams and Franklin. It would probably seem to him at first sight a bewildering document, with many phrases crossed out, numerous interlineations, and whole paragraphs enclosed in brackets. Can this be the ‘original paper’ which Jefferson refers to? Can this be the Rough Draft which Jefferson submitted to Franklin and Adams?

Yes and no. Jefferson seemed not to be aware that future students of history would wish to see the ‘original paper’ just as he wrote it; on the contrary, this precious sheet was to him a rough draft indeed, upon which he could conveniently indicate whatever changes might be made in the process of getting the Declaration through the Committee of Five, and afterward through Congress. The Rough Draft in its present form is thus the ‘original paper,’ together with all, or nearly all, the corrections, additions, and erasures made between the day on which Jefferson submitted it to Franklin and Adams and the 4 of July when Congress adopted the Declaration in its final form. The inquiring student, if he has the right kind of curiosity, will not after all be disappointed to learn this; on the contrary, he will be delighted at the prospect of reading, in this single document, with some difficulty it is true, the whole history of the drafting of the Declaration of Independence.

In this history there are obviously three stages of importance: the Declaration as originally written by Jefferson; the Declaration as submitted by the Committee of Five to Congress; the Declaration as finally adopted. The Declaration as finally adopted is to be found in the Journals of Congress; but that ‘fair copy’ which Jefferson speaks of as the report of the Committee of Five has not been preserved;1 while the original Rough Draft, as we have seen, seems to have been used by Jefferson as a memorandum upon which to note the later changes. How then can we reconstruct the text of the Declaration as it read when Jefferson first submitted it to Franklin and Adams? For example, Jefferson first wrote “we hold these truths to be sacred &undeniable.” In the Rough Draft as it now reads, the words “sacred &undeniable” are crossed out, and “self-evident” is written in above the line. Was this correction made by Jefferson in process of composition? Or by the Committee of Five? Or by Congress? There is nothing in the Rough Draft itself to tell us. As it happens, John Adams made a copy of the Declaration which still exists.1 Comparing this copy with the corrected Rough Draft, we find that it incorporates only a very few of the corrections: one of the two corrections which Adams himself wrote into the Rough Draft; one, or possibly two, of the five corrections which Franklin wrote in; and eight verbal changes apparently in Jefferson’s hand. This indicates that Adams must have made his copy from the Rough Draft when it was first submitted to him; and we may assume that the eight verbal changes, if in Jefferson’s hand, which we find incorporated in Adams’ copy, were there when Jefferson first submitted the Draft to Adams — that is, they were corrections which Jefferson made in process of composing the Rough Draft in the first instance. With Adams’ copy in hand it is therefore possible to reconstruct the Rough Draft as it probably read when first submitted to Franklin.

THE ROUGH DRAFT

(as it probably read when Jefferson first submitted it to Franklin.)1

A Declaration by the Representatives of the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, in General Congress Assembled.

When in the course of human events it becomes necessary for a people to advance from that subordination in which they have hitherto remained, & to assume among the powers of the earth the equal & independent station to which the laws of nature & of nature’s god entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the change.

We hold these truths to be self-evident;1 that all men are created equal & independent; that from that equal creation they derive rights inherent & inalienable,1 among which are the preservation of life, & liberty, & the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these ends, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed; that whenever any form of government shall become destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or to abolish it, & to institute new government, laying it’s foundation on such principles & organizing it’s powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety & happiness. prudence indeed will dictate that governments long established should not be changed for light & transient causes:1 and accordingly all experience hath shewn that mankind are more disposed to suffer while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. but when a long train of abuses & usurpations, begun at a distinguished period, & pursuing invariably the same object, evinces a design to reduce them to arbitrary power, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such government & to provide new guards for their future security. such has been the patient sufferance of these colonies; & such is now the necessity which constrains them to expunge their former systems of government. the history of his present majesty is a history of unremitting injuries and usurpations, among which no one fact stands single or solitary to contradict the uniform tenor of the rest, all of which have in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over these states. to prove this, let facts be submitted to a candid world, for the truth of which we pledge a faith yet unsullied1 by falsehood.

he has refused his assent to laws the most wholesome and necessary for the public good:

he has forbidden his governors to pass laws of immediate1 & pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has neglected utterly to attend to them.

he has refused to pass other laws for the accomodation of large districts of people unless those people would relinquish the right of representation in the legislature, a right inestimable to them & formidable to tyrants only:

he has dissolved Representative houses repeatedly & continually, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people:

he has refused for a long space of time to cause others to be elected, whereby the legislative powers, incapable of annihilation, have returned to the people at large for their exercise, the state remaining in the meantime exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, & convulsions within:

he has endeavored to prevent the population of these states; for that purpose obstructing the laws for naturalization of foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither; & raising the conditions of new appropriations of lands:

he has suffered the administration of justice totally to cease in some of these colonies, refusing his assent to laws for establishing judiciary powers:

he has made our judges dependent on his will alone, for the tenure of their offices, and amount of their salaries:

he has erected a multitude of new offices by a self-assumed power, & sent hither swarms of officers to harrass our people & eat out their substance:

he has kept among us in times of peace standing armies & ships of war:

he has affected to render the military, independent of & superior to the civil power:

he has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitutions1 and unacknoleged by our laws; giving his assent to their pretended acts of legislation, for quartering large bodies of armed troops among us;

for protecting them by a mock-trial from punishment for any murders which they should commit on the inhabitants of these states;

for cutting off our trade with all parts of the world;

for imposing taxes on us without our consent;

for depriving us of the benefits of trial by jury;

for transporting us beyond seas to be tried for pretended offenses;

for taking away our charters, & altering fundamentally the forms of our governments;

for suspending our own legislatures & declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever:

he has abdicated government here, withdrawing his governors, & declaring us out of his allegiance & protection:

he has plundered our seas, ravaged our coasts, burnt our towns & destroyed the lives of our people:

he is at this time transporting large armies of foreign mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation & tyranny, already begun with circumstances of cruelty & perfidy unworthy the head of a civilized nation:

he has endeavored to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers the merciless Indian savages, whose known rule of warfare is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes, & conditions of existence:

he has incited treasonable insurrections of our fellow citizens, with the allurements1 of forfeiture & confiscation of our property:

he has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating it’s most sacred rights2 of life & liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither. this piratical warfare, the opprobrium of infidel powers, is the warfare of the Christian king of Great Britain. [determined to keep open a market where MEN should be bought & sold,] he has prostituted his negative for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or to restrain this execrable commerce determining to keep open a market where MEN should be bought & sold:3 : and that this assemblage of horrors might want no fact of distinguished die, he is now exciting those very people to rise in arms among us, and to purchase that liberty of which he has deprived them, by murdering the people upon whom he also obtruded them: thus paying off former crimes committed against the liberties of one people, with crimes which he urges them to commit against the lives of another.

in every stage of these oppressions we have petitioned for redress in the most humble terms; our repeated petitions have been answered by repeated injury.1 a prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a people who mean to be free. future ages will scarce believe that the hardiness of one man, adventured within the short compass of twelve years only, on so many acts of tyranny without a mask, over a people fostered & fixed in principles2 of liberty.

Nor have we been wanting in attentions to our British brethren. we have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend a jurisdiction over these our states. we have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration & settlement here, no one of which could warrant so strange a pretension: that these were effected at the expence of our own blood & treasure, unassisted by the wealth or the strength of Great Britain: that in constituting indeed our several forms of government, we had adopted one common king, thereby laying a foundation for perpetual league & amity with them: but that submission to their parliament was no part of our constitution, nor ever in idea, if history may be credited: and we appealed to their native justice & magnanimity, as well as to the ties of our common kindred to disavow these usurpations which were likely to interrupt our correspondence & connection. they too have been deaf to the voice of justice & of consanguinity, & when occasions have been given them, by the regular course of their laws, of removing from their councils the disturbers of our harmony, they have by their free election re-established them in power. at this very time too they are permitting their chief magistrate to send over not only soldiers of our common blood, but Scotch & foreign mercenaries to invade & deluge us in blood. these facts have given the last stab to agonizing affection, and manly spirit bids us to renounce forever these unfeeling brethren. we must endeavor to forget our former love for them, and to hold them as we hold the rest of mankind, enemies in war, in peace friends. we might have been a free & a great people together; but a communication of grandeur & of freedom it seems is below their dignity. be it so, since they will have it: the road to happiness & to glory is open to us too; we will climb it apart from them, and acquiesce in the necessity which denounces our eternal separation!

We therefore the representatives of the United States of America in General Congress assembled do, in the name & by authority1 of the good people of these states, reject and renounce all allegiance & subjection to the kings of Great Britain & all others who may hereafter claim by, through, or under them; we utterly dissolve and break off all political connection which may have heretofore subsisted between us & the people or parliament of Great Britain; and finally we do assert and declare these colonies to be free and independent states, and that as free & independent states they shall hereafter have full power to levy war, conclude peace, contract alliances, establish commerce, & to do all other acts and things which independent states may of right do. And for the support of this declaration we mutually pledge to each other our lives, our fortunes, &our sacred honour.

Such, substantially, must have been the form of the Rough Draft when Jefferson first submitted it to Franklin. Between that day, whenever it was, and the 28 of June when the report of the Committee of Five was presented to Congress (it will presently appear how the report of the Committee can be approximately reconstructed), a total of twenty-six alterations were made in the Rough Draft. Twenty-three of these were changes in phraseology — two in Adams’ hand, five in Franklin’s, and sixteen apparently in Jefferson’s. Besides these verbal changes, three entirely new paragraphs were added. If this be true, what are we to make of Jefferson’s account of the matter in his letter to Madison? In this letter, quoted above, Jefferson says that having prepared the Draft he submitted it to “Dr. Franklin and Mr. Adams requesting their corrections;….their alterations were two or three only, and merely verbal. I then wrote a fair copy, reported it to the committee, and from them, unaltered to the Congress.” Jefferson here asserts that no changes were made in the Committee, and he implies that none except those in the handwriting of Franklin and Adams were made before the ‘fair copy’ was presented to the Committee. Either in the assertion or in the implication Jefferson’s statement must be inaccurate.

Jefferson was probably right in the assertion that no changes were made in the Committee. He tells us that he submitted the Draft to Franklin and Adams first because they were the men whose corrections he most wished to have the benefit of. Jefferson, Franklin, and Adams were themselves a majority of the Committee; and if the draft was satisfactory to them it is quite likely that it would pass the Committee without change. Besides, there is no evidence to contradict Jefferson’s statement on this point. What I suppose then is that the twenty-six alterations were all made before the ‘fair copy’ (or the Rough Draft, if Jefferson was mistaken in thinking there was a ‘fair copy’) was submitted to the Committee, and that these changes were the result of at least two, perhaps more, consultations between Jefferson and Franklin, and between Jefferson and Adams. Jefferson must have submitted the Draft to both Franklin and Adams at least twice, because the copy which Adams took contains only two of the five corrections which Franklin wrote into the Draft, and only one of the two which Adams himself wrote in. It was after Adams made his copy that he wrote in the second of his own corrections, that Franklin wrote in three of his corrections, and that Jefferson wrote in the three new paragraphs and sixteen verbal changes. Now there is nothing to show whether the corrections in Jefferson’s hand were made before or after the later corrections by Franklin and Adams. I think we may assume that Jefferson, having written in three new paragraphs and sixteen verbal changes, would scarcely venture to make a ‘fair copy’ for the Committee, or, if there was no fair copy, would he be likely to present the Rough Draft thus corrected to the Committee, without having first submitted the Draft thus amended to Franklin and Adams for their final approval. Is it not then likely that it was on the occasion of this final submission of the corrected Draft to Franklin and Adams that they wrote in the corrections which appear in their hands but are not in the copy which Adams made?

The order of events in correcting the Rough Draft cannot in most respects be known; but I should guess that it was somewhat as follows. Having prepared the Draft, in which were eight slight verbal corrections made in process of composition, Jefferson first submitted it to Franklin. Franklin then wrote in one, and probably two, of the five corrections that appear in his hand. Where the Draft read, “and amount of their salaries,” Franklin changed it to read, “and the amount & payment of their salaries.” A second correction by Franklin was probably made at this time also. Jefferson originally wrote “reduce them to arbitrary power.” Franklin’s correction reads “reduce them under absolute Despotism.” But Adams’ copy reads “reduce them under absolute power,” which is neither the original nor the corrected reading, but a combination of both. Adams may of course have made a mistake in copying (he made a number of slight errors in copying); or it may be that at this time Franklin wrote in “under absolute” in place of “to arbitrary,” and that not until later, after Adams made his copy, was “power” crossed out and “Despotism” written in. In the original manuscript, “Despotism” appears to have been written with a different pen, or with heavier ink, than “under Absolute,” as if written at a different time. At all events, not more than two of Franklin’s five corrections had been made when Jefferson submitted the Draft to Adams. Adams then wrote in one of his two corrections: where Jefferson had written “for a long space of time,” Adams added “after such dissolutions.” Having made this correction, Adams made his copy of the Draft as it then read, and, we may suppose, returned the Draft to Jefferson.

After receiving the Draft from Adams, Jefferson wrote in, at least the greater part of the sixteen verbal changes, and three new paragraphs. The verbal changes he probably made on his own initiative; they were mere improvements in phraseology, such as would be likely to occur to him upon rereading. He may likewise have added the three new paragraphs on his own initiative; but I think it extremely likely that Adams suggested the addition of the paragraph about calling legislative bodies at places remote from their public records. This had actually occurred in Massachusetts, and who more likely than Adams to remember it, or to wish to have it included in the list of grievances? This at least we know, that Jefferson wrote out on a slip of paper the following paragraph:

he has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, & distant from the depository of their public records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures.

The slip was then pasted at one end to the Rough Draft at the place where occurs the paragraph beginning, “he has dissolved Representative houses repeatedly and continually.”1 The two other paragraphs which Jefferson added after Adams returned the Draft are the one beginning, “for abolishing the free system of English laws,”2 and the one beginning, “he has constrained others taken captives on the high seas.”3

In whatever order these changes were made, and whether after only one or after several conferences with Franklin or Adams, it may I think be assumed that Jefferson would submit the Rough Draft, after these changes were incorporated, to Franklin and Adams for their final approval before presenting the ‘fair copy’ (or the Rough Draft, if it was the Rough Draft) to the Committee. Now it may well have been at the time of this last inspection, after all other changes had been made, that Adams wrote in the second, and Franklin the last three of the corrections that appear in their handwriting. If this was in fact the order of events, it is not difficult to understand that Jefferson should have recalled the affair as he related it to Madison in 1823: “their alterations were two or three only, and merely verbal. I then wrote a fair copy, reported it to the Committee, & from them, unaltered to the Congress.”

So far we have assumed that the three new paragraphs and the sixteen verbal changes in Jefferson’s hand were written into the Rough Draft before it was submitted to the Committee of Five. But how do we know this, since Jefferson’s ‘fair copy’ has not been preserved? How do we know these changes were not made by Congress? Fortunately, it is possible to reconstruct the report of the Committee of Five substantially as it must have read. We have a copy of the Declaration which Jefferson made and sent to Richard H. Lee on the 8 of July, 1776, and which, in a letter to Lee of that date, he says is the Declaration “as originally framed.”1 This copy, now possessed by the American Philosophical Society, and printed in facsimile in the Proceedings of the society,2 is quite obviously not the Declaration ‘as originally framed’ — that is, as Jefferson framed it before submitting it to Franklin and Adams for the first time — because it differs strikingly from the copy which Adams made. It was probably made from the Rough Draft at about the time that the Committee of Five submitted its report to Congress; and if that report was made, as Jefferson says, in the form of a ‘fair copy,’ it is safe to assume that it was intended to be a duplicate of the fair copy.3 What Jefferson meant by the phrase “as originally framed” was “as originally reported.” This is confirmed by the fact that Jefferson described another copy of the Declaration, and practically identical with the Lee copy, by saying that it is the Declaration “as originally reported.” This latter copy is the one which he wrote into his “Notes,” later printed as part of his Autobiography.1 Finally, during the debates in Congress or afterward, Jefferson indicated on the Rough Draft the changes made by Congress by bracketing the parts omitted. Thus the Lee copy, the copy in Jefferson’s “Notes,” and the Rough Draft exclusive of the corrections made in connection with the bracketed parts, furnish us with three texts which were intended to conform to the report of the Committee of Five. The most reliable of these texts is probably the Lee copy. The text given below is made by reproducing the Rough Draft exclusive of all corrections that do not appear in the Lee copy; that is, it is the Rough Draft as it must have read when Jefferson made the Lee copy, assuming that he made the Lee copy from the Rough Draft, and made no errors in copying. If Jefferson made a ‘fair copy’ for the Committee, he may of course have made the Lee copy from that fair copy instead of from the Rough Draft. In either case it can hardly be supposed that he made any changes deliberately; and if he made any errors (he apparently made at least one),2 they were probably slight. The corrections printed in roman are those which, being incorporated in Adams’ copy, I have assumed were made by Jefferson in the process of composition before he first submitted the Draft to Franklin. All other corrections and additions are printed in italics. Where the reading of the Lee copy differs from that of the copy in the “Notes,” excepting differences in punctuation and capitalization, I have noted the difference in footnotes.

THE ROUGH DRAFT

as it probably read when Jefferson made the ‘fair copy’ which was presented to Congress as the report of the Committee of Five.

A Declaration by the Representatives of the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, in General Congress Assembled.

When in the course of human events it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political hands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth the separate and equal station to which the laws of nature & of nature’s god entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men are created equal that they are endowed by their creator with inherent & inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, & the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed; that whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or to abolish it, & to institute new government, laying it’s foundation on such principles & organizing it’s powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety & happiness. prudence indeed will dictate that governments long established should not be changed for light & transient causes: and accordingly all experience hath shewn that mankind are more disposed to suffer while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. but when a long train of abuses & usurpations, begun at a distinguished period, & pursuing invariably the same object, evinces a design to reduce them*under absolute Despotism it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such government & to provide new guards for their future security. such has been the patient sufferance of these colonies; & such is now the necessity which constrains them to expunge their former systems of government. the history of*the present king of Great Britain is a history of unremitting injuries and usurpations, among which appears no solitary fact to contradict the uniform tenor of the rest, but all have in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over these states. to prove this, let facts be submitted to a candid world, for the truth of which we pledge a faith yet unsullied by falsehood.

he has refused his assent to laws the most wholesome and necessary for the public good:

he has forbidden his governors to pass laws of immediate & pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has neglected utterly1 to6 attend to them.

he has refused to pass other laws for the accomodation of large districts of people unless those people would relinquish the right of representation in the legislature, a right inestimable to them & formidable to tyrants only:

he has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable distant from the depository of their public records for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures:

he has dissolved, Representative houses repeatedly & continually, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people:

he has refused for a long*time after such dissolutions to cause others to be elected, whereby the legislative powers, incapable of annihilation, have returned to the people at large for their exercise, the state remaining in the meantime exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, & convulsions within:

he has endeavored to prevent the population of these states; for that purpose obstructing the laws for naturalization of foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither; & raising the conditions of new appropriations of lands:

he has suffered the administration of justice totally to cease in some of these states refusing his assent to laws for establishing judiciary powers:

he has made our judges dependent on his will alone, for the tenure of their offices, and†the amount and payment of their salaries:

he has erected a multitude of new offices by a self-assumed power, & sent hither swarms of officers to harrass our people & eat out their substance:

he has kept among us in times of peace standing armies & ships of war without the consent. of our legislatures:

he has effected to render the military, independent of & superior to the civil power:

he has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitutions and unacknoleged by our laws; giving his assent to their acts of pretended legislation,

for quartering large bodies of armed troops among us;

for protecting them by a mock-trial from punishment for any murders which they should commit on the inhabitants of these states;

for cutting off our trade with all parts of the world;

for imposing taxes on us without our consent;

for depriving us of the benefits of trial by jury;

for transporting us beyond seas to be tried for pretended offenses;

for abolishing the free system of English laws in a neighboring province, establishing therein an arbitrary government, and enlarging it’s boundaries so as to render it at once an example fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these states;

for taking away our charters,*abolishing our most valuable laws & altering fundamentally the forms of our governments;

for suspending our own legislatures & declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever:

he has abdicated government here, withdrawing his governors, & declaring us out of his allegiance & protection:

he has plundered our seas, ravaged our coasts, burnt our towns & destroyed the lives of our people:

he is at this time transporting large armies of foreign mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation & tyranny, already begun with circumstances of cruelty & perfidy unworthy the head of a civilized nation:

he has endeavored to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers the merciless Indian savages, whose known rule of warfare is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes, & conditions of existence:

he has incited1 treasonable insurrections of our fellow-citizens, with the allurements of forfeiture & confiscation of our property:

he has constrained others2 taken captives on the high seas to bear arms against their country to become the executioners of their friends brethren, or to fall themselves by their hands.

he has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating it’s most sacred rights of life & liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither. this piratical warfare, the opprobrium of infidel powers, is the warfare of the Christian king of Great Britain. determined to keep open a market where MEN should be bought sold, he has prostituted his negative for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or to restrain this execrable commerce and that this assemblage of horrors might want no fact of distinguished die, he is now exciting those very people to rise in arms among us, and to purchase that liberty of which he has deprived them, by murdering the people upon whom he also obtruded them; thus paying off former crimes committed against the liberties of one people, with crimes which he urges them to commit against the lives of another.

The pusillanimous idea that we had friends in England worth keeping terms with, still haunted the minds of many. For this reason those passages which conveyed censures on the people of England were struck out, lest they should give them offense. The clause too, reprobating the enslaving the inhabitants of Africa, was struck out in complaisance to South Carolina and Georgia, who had never attempted to restrain the importation of slaves, and who on the contrary still wished to continue it. Our Northern brethren also I believe felt a little tender under those censures; for tho’ their people have very few slaves themselves yet they had been pretty considerable carriers of them to others.1

In a letter to Robert Walsh, December 4, 1818, Jefferson wrote as follows:

The words ’scotch and other foreign auxillaries’ excited the ire of a gentleman or two of that country. Severe strictures on the British king, in negativing our repeated repeals of the law which permitted the importation of slaves, were disapproved by some Southern gentlemen, whose reflections were not yet matured to the full abhorrence of that traffic. Although the offensive expressions were immediately yielded, these gentlemen continued their depredations on other parts of the instrument.2

The Journal of Congress gives only the form of the Declaration as finally adopted. In what is called the ‘rough Journal’ the entry for July 4 is as follows:

Mr. Harrison reported that the Committee of the Whole Congress have agreed to a Declaration which he delivered in. The Declaration being read was agreed to as follows.3

What follows in the ‘rough Journal’ is a printed copy of the Declaration — a copy printed by Dunlap by order of Congress and under the supervision of the Committee of Five. In what is known as the ‘corrected Journal’ the Declaration is written in.1 The copy in the corrected Journal should, one would suppose, be the more authoritative text. Such seems, however, not to be the case. Apart from differences in punctuation and capitalization, in which the corrected Journal follows more closely the practice of Jefferson, the only differences in the two texts are the following: where the rough Journal reads, “for quartering large bodies of armed troops among us,” the corrected Journal reads, “for quartering large bodies of troops among us”; and where the rough Journal reads, “they too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity,” the corrected Journal reads, “they too have been deaf to the voice of justice &consanguinity.” The reading of the rough Journal in these two cases is the same as that of every other text we have, including the engrossed parchment copy. It seems clear, therefore, that these changes in the corrected Journal were not ‘corrections’ but simply inadvertent omissions. The copy in the rough Journal should thus be taken as the most authoritative text. If then, as I have assumed, the copy which Jefferson sent to Richard H. Lee is the nearest we can come to the ‘fair copy’ which was the report of the Committee of Five, a comparison of the Lee copy with the copy in the rough Journal will give us the changes made by Congress as accurately as it is possible to determine them. The text given below is the Lee copy, except for one reading in the last paragraph where Jefferson probably made an error in copying, with the parts omitted by Congress crossed out and the parts added interlined in italics.

THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE

(as it reads in the Lee copy, which is probably the same as the report of the Committee of Five, with parts omitted by Congress crossed out and the parts added interlined in italics.)

In every stage of these oppressions, we have petitioned for redress in the most humble terms; our repeated petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. a prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people

Nor have we been wanting in attentions to our British brethren. we have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. we have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here, we have appealed to their native justice & magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the tyes of our common kindred, to disavow these usurpations, which would inevitably interrupt our connections & correspondence. they too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity1 ; we must therefore acquiesce in the necessity which denounces our separation and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, enemies in war, in peace friends.!

We therefore the Representatives of the United states of America in General Congress assembled, appealing to the supreme judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions do, in the name & by authority of the good people of these colonies, solemnly publish and declare, that these united colonies are and of right ought to be free and independent states; that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the state of Great Britain is ought to be totally dissolved;;1 & that as free & independent states, they have full power to levy war, conclude peace, contract alliances, establish commerce, & to do all other acts and things which independent states may of right do. And for the support of this declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine providence, we mutually pledge to each other our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor.

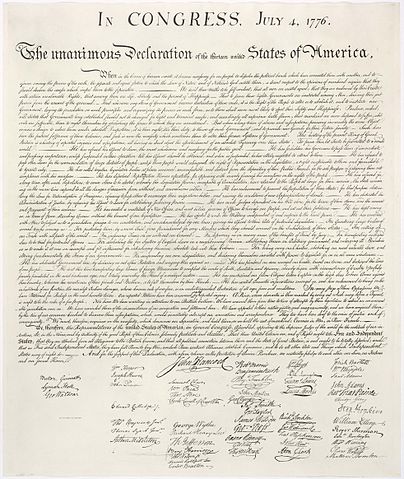

Contrary to a tradition early established and long held, the Declaration was not signed by the members of Congress on July 4. Neither the rough nor the corrected Journal shows any signatures, except that the printed copy in the rough Journal closes with these words, of course in print: “Signed by order and in behalf of the Congress, John Hancock, President.” The secret domestic Journal for July 19 contains the following entry: “Resolved that the Declaration passed on the 4th be fairly engrossed.” And in the margin there is added: “Engrossed on parchment with the title and stile of “The Unanimous Declaration of the 13 United States of America,” and that the same when engrossed be signed by every member of Congress.” On August 2 occurs the following entry: “The Declaration of Independence being engrossed and compared at the table was signed by the members.” Certain members, being absent on the 2 of August, signed the engrossed copy at a later date.1 The engrossed parchment copy, carefully preserved at Washington, is identical in phraseology with the copy in the rough Journal.1 The paragraphing, except in one instance, is indicated by dashes; the capitalization and punctuation, following neither previous copies, nor reason, nor the custom of any age known to man, is one of the irremediable evils of life to be accepted with becoming resignation. Two slight errors in engrossing have been corrected by interlineation.

THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE

(as it reads in the parchment copy.)

The Unanimous Declaration of the Thirteen United States of America.

When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands, which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation. — We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. — That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, — That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security. — Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world. — He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good. — He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them. — He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only. — He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures. — He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people. — He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the Legislative powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the meantime exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within. — He has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands. — He has obstructed the Administration of Justice, by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary powers. — He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone, for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries. — He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harrass our people, and eat out their substance. — He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures. — He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil power. — He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation. — For quartering large bodies of armed troops among us: — For protecting them, by a mock Trial, from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States: — For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world: — For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent: — For depriving us in many cases, of the benefits of Trial by Jury: — For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offenses: — For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighboring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies: — For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws, and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments: — For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever. — He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us. — He has plundered our seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people. — He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty &perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation. — He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands. — He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions. In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people. Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our Brittish brethren.We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the ties of our common kindred to disavow these usurpations, which would inevitably interrupt our connections and correspondence. They too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends. —

We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. — And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.

The signatures on the parchment copy, of which only a few are now legible, are given below.

| John Hancock. | Fran.s Lewis. |

| Samuel Chase. | Lewis Morris. |

| Wm Paca. | Rich.d. Stockton. |

| Tho.s Stone. | Jn.oWitherspoon. |

| Charles Carroll of Carrollton. | Fra.s Hopkinson. |

| George Wythe. | John Hart. |

| Richard Henry Lee. | Abra Clark. |

| Th Jefferson. | Josiah Bartlett. |

| Benja Harrison. | Wm Whipple. |

| Tho.s Nelson jr. | SamlAdams. |

| Francis Lightfoot Lee. | John Adams. |

| Carter Braxton. | Robt Treat Paine. |

| Robt Morris. | Elbridge Gerry. |

| Benjamin Rush. | Step Hopkins. |

| Benj.a Franklin. | William Ellery. |

| John Morton. | Roger Sherman. |

| Geo Clymer. | Sam1Huntington. |

| JasSmith. | WmWilliams. |

| Geo. Taylor. | Oliver Wolcott. |

| James Wilson. | Matthew Thornton. |

| Geo. Ross. | WmHooper. |

| Caesar Rodney. | Joseph Hewes. |

| Geo Read. | John Penn. |

| Tho M: Kean. | Edward Rutledge. |

| Wm Floyd. | Thos Heyward Junr. |

| Phil. Livingston. | Thomas Lynch Junr. |

| Arthur Middleton. | Lyman Hall. |

| Button Gwinnett. | Geo Walton. |

[1]Ibid., 512.

[2]Ibid., 514.

[1]Writings of Thomas Jefferson (ed. 1869), VII, 304.

[1]The Declaration of Independence: Its History. New York. 1906. Whether the Rough Draft which Jefferson refers to in his letter to Madison was the first draft which he made for the Declaration is not known. But it appears that he used, in preparing the Declaration, a manuscript now in the Library of Congress, which is in Jefferson’s hand, and is endorsed by him as follows: “Constitution of Virginia first ideas of Th: J. communicated to a member of the Convention.” The first page of this manuscript is in the form of a series of reasons why Virginia repudiates her allegiance to George III. The charges against the king which appear in the Rough Draft seem to have been copied, in many cases verbatim, from this manuscript. Cf. Fitzpatrick, J. C. “The Manuscript from which Jefferson Wrote the Declaration of Independence”; in Daughters of the American Revolution Magazine, LV, 363.

[1]It is possible that Jefferson was mistaken in thinking that he made a ‘fair copy’ for the Committee. If he made such a copy, and if it was handed in as the report of the Committee, it seems odd that it was not preserved among the papers of Congress. If there was such a copy, it was undoubtedly that copy as amended by Congress that was used by Dunlap for printing the text that was pasted into the ‘rough’ Journal; and it is at least conceivable that it was inadvertently left with the printer, and so lost. On the other hand, if there was no ‘fair copy,’ we must suppose that the corrected Rough Draft was itself the report of the Committee. I find it difficult to suppose that Jefferson would have presented, as the formal report of the Committee, a paper so filled with erasures and interlineations that in certain parts no one but the author could have read it without a reading glass. Besides, if the Rough Draft was handed in as the report of the Committee it should bear the endorsement of the Secretary of Congress, Charles Thompson. No such endorsement appears on the Rough Draft. Again, if the Rough Draft was used as the report of the Committee, one would suppose that the amendments made by Congress would be indicated on it in the hand of Charles Thompson; whereas they are in fact in the hand of Jefferson. On the whole, the reasons for supposing that Jefferson made a ‘fair copy,’ which was used as the report of the Committee and afterward lost, seem to me more convincing than the reasons for supposing that the Rough Draft itself was used as the report of the Committee.

[1]This copy is in the possession of the Massachusetts Historical Society. It is printed in Hazelton, op. cit., 306 ff; in Journals of Congress (Ford ed.), V, 491; and in Writings of Jefferson (Ford ed.), II, 42. For a brief discussion of the document, see Hazelton, 346.

[1]The text here given is identical with the Adams copy except, (1) the corrections of Franklin and Adams appearing on the Rough Draft and incorporated by Adams in his copy are omitted, (2) the spelling, capitalization, and punctuation of the Rough Draft have been followed, (3) in a number of instances where Adams obviously made slips in copying, the Rough Draft is followed. These slips, in each case, are indicated in the footnotes.

[1]It is not clear that this change was made by Jefferson. The handwriting of “self-evident” resembles Franklin’s.

[1]Adams’ copy reads “unalienable.” This is the reading of the Declaration as finally adopted; but as the change is not indicated on the Rough Draft, Adams must have deliberately or inadvertently made the change in copying. See below, p. 175, note 1.

[1]Adams’ copy reads “or transient.”

[1]Adams’ copy reads “as yet unsullied.”

[1]Adams’ copy reads “an immediate.”

[1]Adams’ copy reads “constitution.”

[1]Adams’ copy reads “allurement.”

[2]Adams’ copy reads “right.”

[3]Adams’ copy reads “an execrable.”

[1]The Rough Draft reads “injuries.” But it is clear that the original form was “injury.” The “y” has been erased and “ies” written in. All of the official texts read “injury,” and all of Jefferson’s own copies of the Declaration read “injury” except the one which he copied into his “Notes.” It seems that Jefferson must have made this change after the Declaration was adopted, since it is unlikely that it would have been rejected by Congress if it had been in the report of the Committee of Five.

[2]Adams’ copy reads “the principles.”

[1]Adams’ copy reads “the authority.”

[1]In the course of time a part of this slip was torn out and lost; but the rest of it, which is in two parts, was pasted down throughout, over, and largely concealing, the paragraph which reads: “he has dissolved Representative houses repeatedly &continually, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people:” Of this paragraph, therefore, only a few words can now be seen on the Rough Draft; and of the paragraph written on the slip, only about two thirds can be seen. At this point the Rough Draft now reads as follows:

he has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncolly for opposing t from the depository of their public records for the sole purpose of fatiguieople: nce with his measures.

The word “continually,” of which only the letters “lly” can now be seen, has the bracket because it was omitted by Congress, and Jefferson bracketed on the Rough Draft those parts omitted by Congress.

[2]This paragraph is written in at the bottom of page 2 of the Rough Draft; there was margin enough there to insert it by writing a very small hand and crowding the lines.

[3]This paragraph is written in on page 3 of the Rough Draft, between the paragraph beginning, “he has incited treasonable insurrections,” and the paragraph beginning, “he has waged cruel war.” Jefferson was able to crowd the new paragraph in because he left a pretty wide space between the lines when he wrote the Rough Draft; but the new paragraph had to be written so close and small that, even apart from the fact that this paragraph does not appear in Adams’s copy, we should know it to be a later Insertion.

[1]Writings of Thomas Jefferson (Ford ed.), II, 59.

[2]Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, XXXVII, 103–106.

[3]Hazelton, op. cit., 306, 344.

[1]Ibid., 171. Writings of Thomas Jefferson (Ford ed.), I, 29.

[2]See Page 170, Note 1.

[*]Dr. Franklin’s handwriting

[*]Mr. Adams’ handwriting

[1]The Rough Draft reads, “he has utterly neglected.” The copy in the “Notes” reads “utterly neglected.” My belief is that this was one of the corrections made by Congress which Jefferson neglected to indicate as he commonly did such corrections, by bracketing the omitted word.

[*]Mr. Adams

[dagger]Dr. Franklin

[*]Dr. Franklin

[1]The copy in the “Notes” reads “excited.”

[2]The copy in the “Notes” reads “our fellow citizens” in place of “others.” This is the reading of the text as adopted by Congress; but as the change does not appear on the Rough Draft, I have assumed that this was a change made by Congress. The paragraph is written in the Rough Draft as here shown, following the paragraph beginning, “he has incited.” Congress changed the order, placing the paragraph beginning “he has constrained” immediately following the one beginning “he is at this time transporting.” The copy in the “Notes” follows the order adopted by Congress.

[1]Writings of Thomas Jefferson (Ford ed.), 1, 28.

[2]Ibid., X, 119–120, note.

[3]Hazelton, op. cit., 170, 306.

[1]Ibid.

[1]The text in the corrected Journal reads “and consanguinity.”

[1]The reading here is not precisely that of the Lee copy. See p. 170, note 1.

[1]For a discussion of this question, see Hazelton, op. cit., Ch. 9.

[1]Ibid., 208, 306