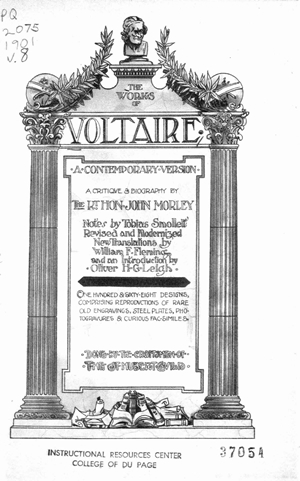

Part of: The Works of Voltaire. A Contemporary Version, in 21 vols. The Works of Voltaire, Vol. VIII The Dramatic Works Part 1

- William F. Fleming (translator)

- Voltaire (author)

Volume 8 of the 21 volume 1901 edition of the Complete Works. It contains 9 plays: Mérope, Olympia, The Orphan of China, Brutus, Mahomet, Amelia, Oedipus, Mariamne, Socrates.