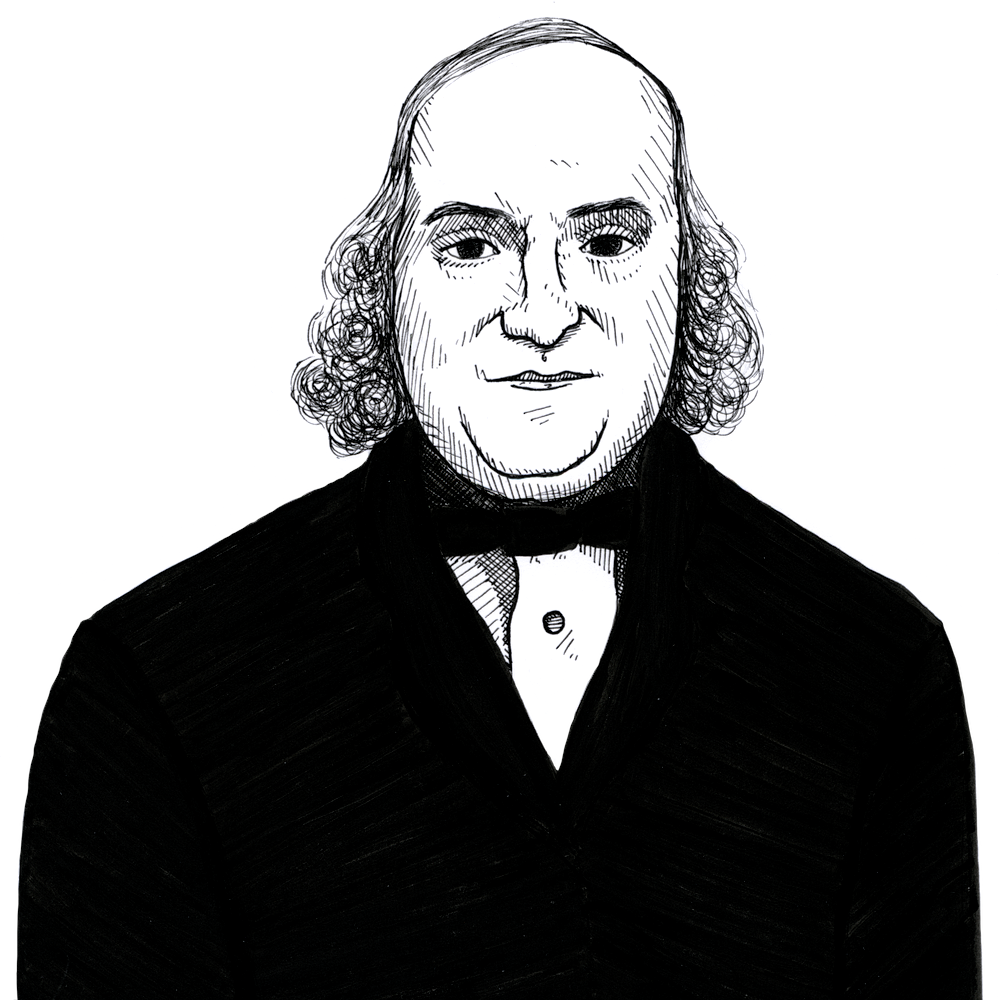

Thomas Hodgskin argues for a Lockean notion of the right to property (“natural”) and against the Benthamite notion that property rights are created by the state (“artificial”) (1832)

Found in: The Natural and Artificial Right of Property Contrasted

Thomas Hodgskin sends a series of letters to one of the most influential Benthamite reformers of the period informing him that his theory of property is incorrect and dangerous to liberty and that he should adopt a more Lockean notion of property rights

Property Rights

I look on a right of property—on the right of individuals, to have and to own, for their own separate and selfish use and enjoyment, the produce of their own industry, with power freely to dispose of the whole of that in the manner most agreeable to themselves, as essential to the welfare and even to the continued existence of society. If, therefore, I did not suppose, with Mr. Locke, that nature establishes such a right—if I were not prepared to shew that she not merely establishes, but also protects and preserves it, so far as never to suffer it to be violated with impunity—I should at once take refuge in Mr. Bentham’s impious theory, and admit that the legislator who established and preserved a right of property, deserved little less adoration than the Divinity himself. Believing, however, that nature establishes such a right, I can neither join those who vituperate it as the source of all our social misery, nor those who claim for the legislator the high honour of being “the author of the finest triumph of humanity over itself.”