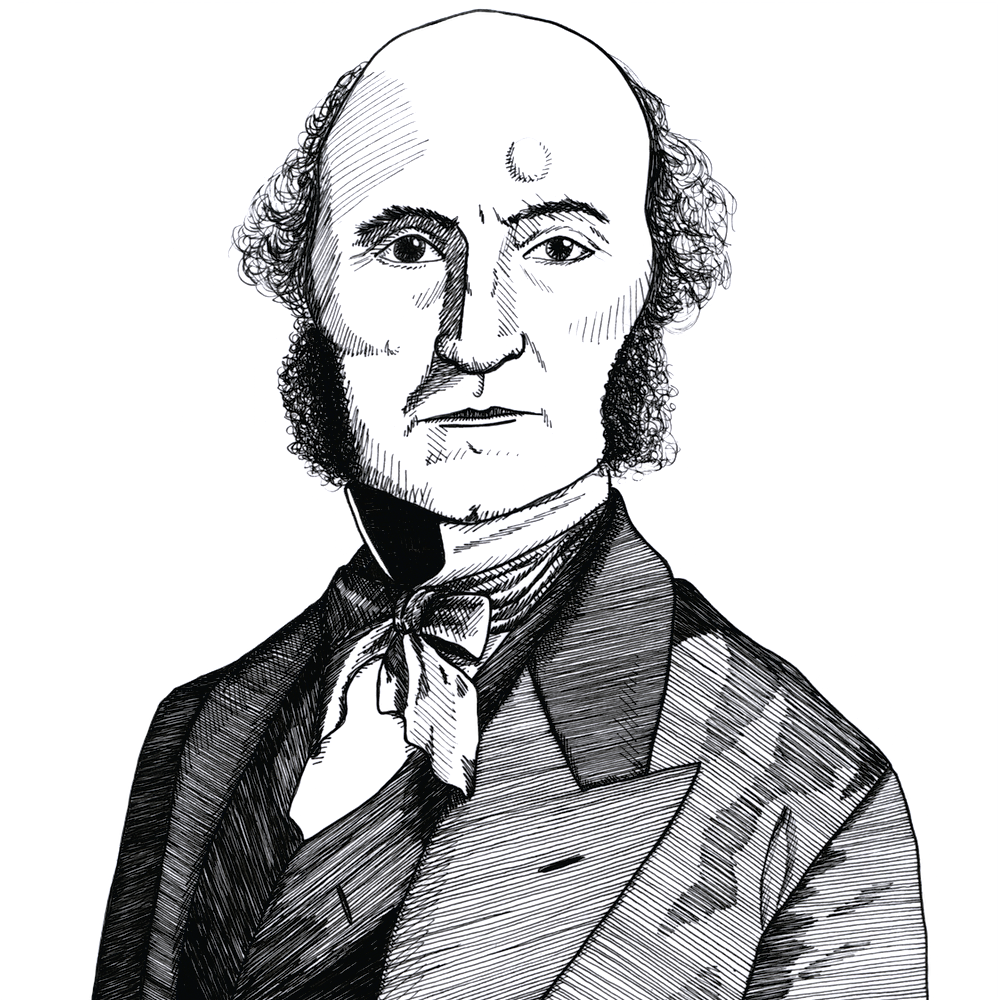

John Stuart Mill on the “atrocities” committed by Governor Eyre and his troops in putting down the Jamaica rebellion (1866)

Found in: The Collected Works of John Stuart Mill, Volume I - Autobiography and Literary Essays

In 1866 John Stuart Mill chaired a committee to look into the brutal repression of a mutiny in Jamaica by Governor Eyre. He spoke on the matter several times in the House of Commons. In his Autobiography he observed that:

Colonies, Slavery & Abolition

A disturbance in Jamaica, provoked in the first instance by injustice, and exaggerated by rage and panic into a premeditated rebellion, had been the motive or excuse for taking hundreds of innocent lives by military violence or by sentence of what were called courts martial, continuing for weeks after the brief disturbance had been put down; with many added atrocities of destruction of property, flogging women as well as men, and a great display of the brutal recklessness which generally prevails when fire and sword are let loose. The perpetrators of these deeds were defended and applauded in England by the same kind of people who had so long upheld negro slavery: and it seemed at first as if the British nation was about to incur the disgrace of letting pass without even a protest, excesses of authority as revolting as any of those for which, when perpetrated by the instruments of other governments, Englishmen can hardly find terms sufficient to express their abhorrence.