John Hobson argues that sport plays an important part in British imperialism for all classes and that the “spirit of adventure” is now played out in the colonies (1902)

Found in: Imperialism: A Study

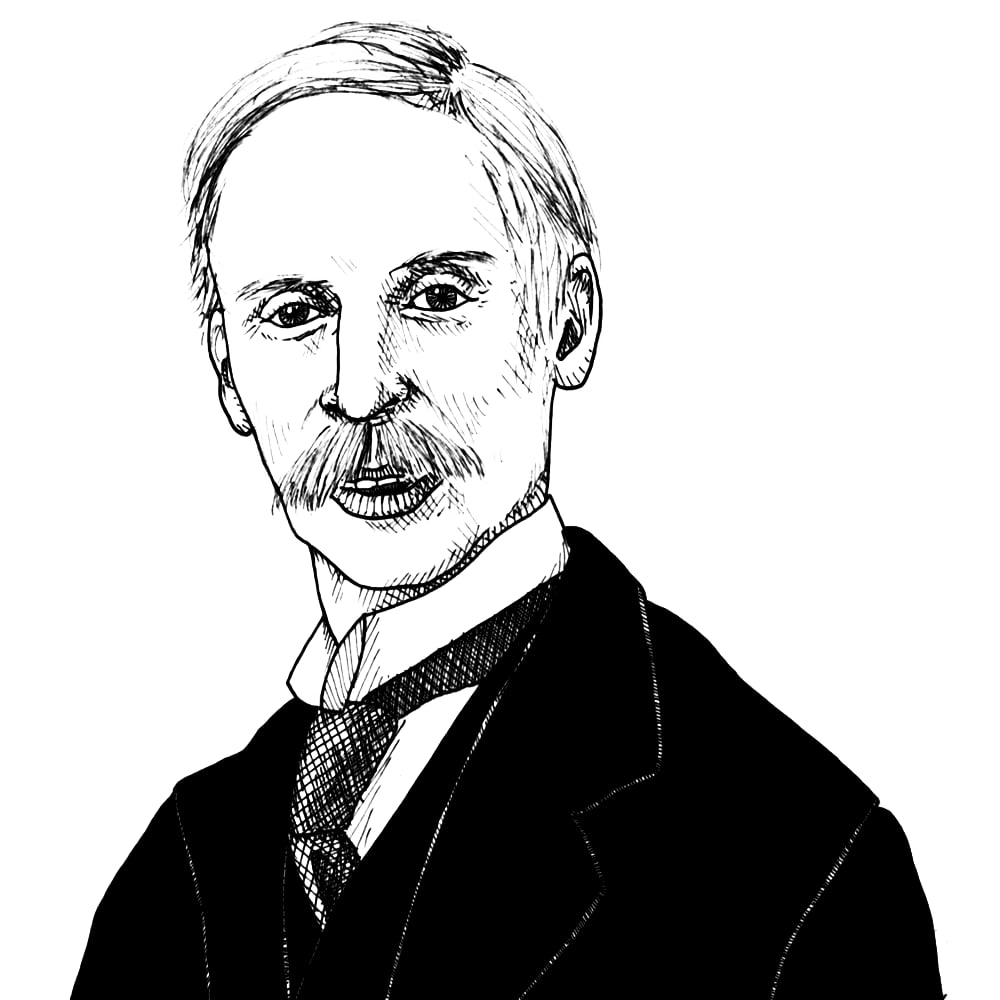

John A. Hobson (1858-1940) was a supporter of the free trade and anti-imperialist ideas of Richard Cobden (1804-1865) and bitterly opposed the Boer War in South Africa (1899-1902). He argued that there was a strong connection between sport and empire in England:

Sport and Liberty

This “spirit of adventure,” especially in the Anglo-Saxon, has taken the shape of “sport,” which in its stronger or “more adventurous” forms involves a direct appeal to the lust of slaughter and the crude struggle for life involved in pursuit. The animal lust of struggle, once a necessity, survives in the blood, and just in proportion as a nation or a class has a margin of energy and leisure from the activities of peaceful industry, it craves satisfaction through “sport,” in which hunting and the physical satisfaction of striking a blow are vital ingredients. The leisured classes in Great Britain, having most of their energy liberated from the necessity of work, naturally specialise on “sport,” the hygienic necessity of a substitute for work helping to support or coalescing with the survival of a savage instinct. As the milder expressions of this passion are alone permissible in the sham or artificial encounters of domestic sports, where wild game disappears and human conflicts more mortal than football are prohibited, there is an ever stronger pressure to the frontiers of civilisation in order that the thwarted “spirit of adventure” may have strong, free play.