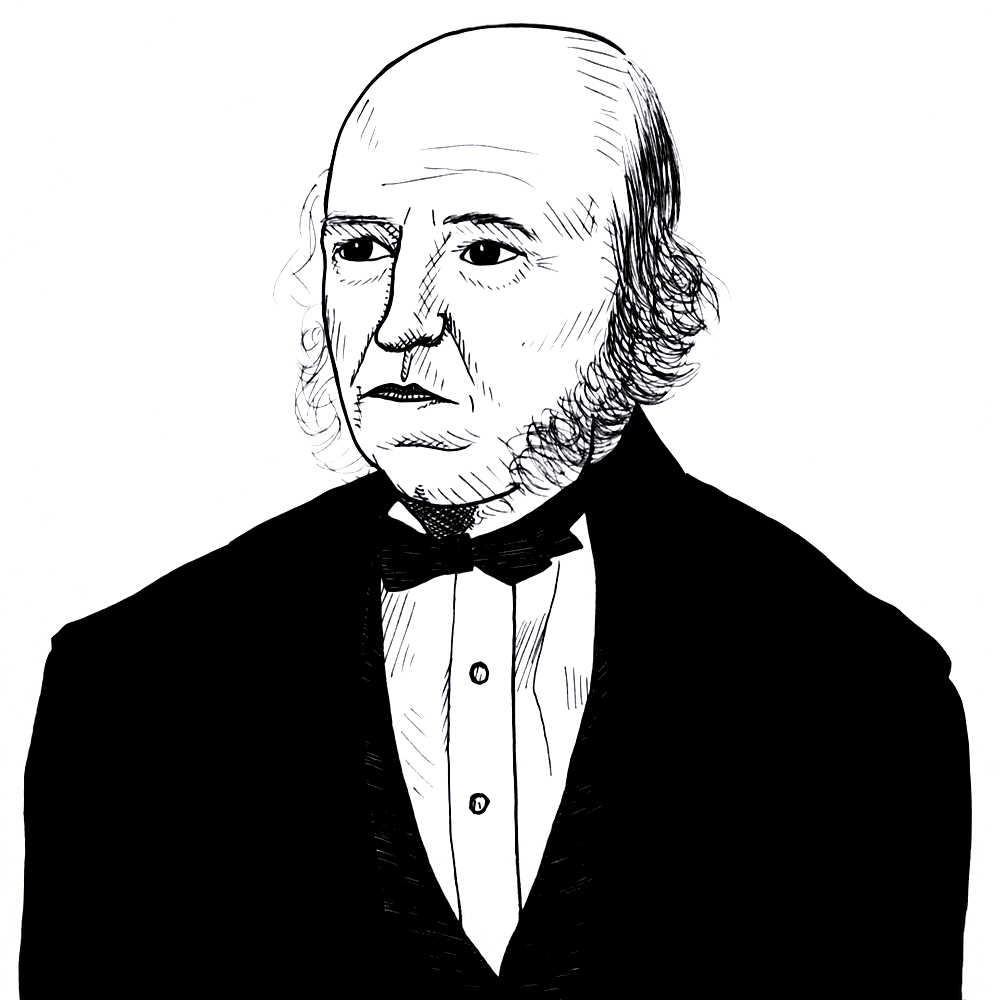

Herbert Spencer on the prospects for liberty (1882)

Found in: Political Institutions, being Part V of the Principles of Sociology

The English radical individualist Herbert Spencer (1820-1903) thought that the prospects for liberty in late 19th century England and America were not good if people continued to believe that the general welfare could be improved by legislation and “wirepulling politicians”:

Liberty

The days when “paper constitutions” were believed in have gone by—if not with all, still with instructed people. The general truth that the characters of the units determine the character of the aggregate, though not admitted overtly and fully, is yet admitted to some extent—to the extent that most politically-educated persons do not expect forthwith completely to change the state of a society by this or that kind of legislation. But when fully admitted, this truth carries with it the conclusion that political institutions cannot be effectually modified faster than the characters of citizens are modified; and that if greater modifications are by any accident produced, the excess of change is sure to be undone by some counter-change. …

When, as in the United States, republican institutions, instead of being slowly evolved, are all at once created, there grows up within them an agency of wirepulling politicians, exercising a real rule which overrides the nominal rule of the people at large. When, as at home, an extended franchise, very soon re-extended, vastly augments the mass of those who, having before been controlled are made controllers, they presently fall under the rule of an organized body that chooses their candidates and arranges for them a political programme, which they must either accept or be powerless. So that in the absence of a duly-adapted character, liberty given in one direction is lost in another.