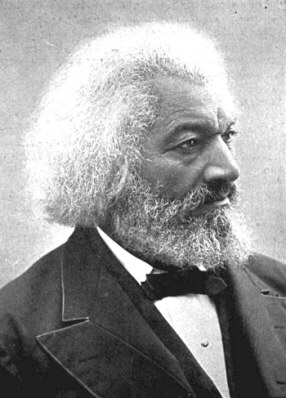

Frederick Douglass on Women’s Right to Vote

Found in: The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass: From 1817-1882

Frederick Douglass, best known as a strong advocate of the abolition of slavery, was also an early and outspoken supporter for women’s rights in general and especially women’s right to vote.

Women’s Rights

Observing woman’s agency, devotion, and efficiency in pleading the cause of the slave, gratitude for this high service early moved me to give favourable attention to the subject of what is called “Woman’s Rights,” and caused me to be denominated a woman’s-rights-man. I am glad to say I have never been ashamed to be thus designated. Recognising not sex, nor physical strength, but moral intelligence and the ability to discern right from wrong, good from evil, and the power to choose between them, as the true basis of Republican Government, to which all are alike subject, and bound alike to obey, I was not long in reaching the conclusion that there was no foundation in reason or justice for woman’s exclusion from the right of choice in the selection of the persons who should frame the laws, and thus shape the destiny of all the people, irrespective of sex.