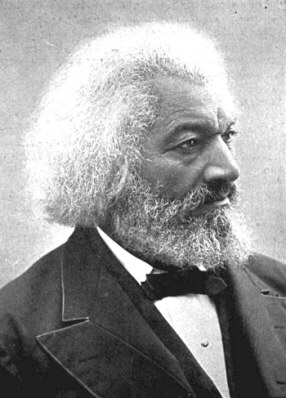

Frederick Douglass on Abraham Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation

Found in: The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass: From 1817-1882

On January 1, 1863, Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. Its limited scope, freeing slaves only in those states “in rebellion against the United States,” did not satisfy abolitionists but did infuriate many in the North who were pro-Union but not anti-slavery.

Colonies, Slavery & Abolition

The Proclamation itself was like Mr. Lincoln throughout. It was framed with a view to the least harm and the most good possible in the circumstances, and with especial consideration of the latter. It was thoughtful, cautious, and well guarded at all points. While he hated slavery, and really desired its destruction, he always proceeded against it in a manner the least likely to shock or drive from him any who were truly in sympathy with the preservation of the Union, but who were not friendly to emancipation. For this he kept up the distinction between loyal and disloyal slaveholders, and discriminated in favour of the one, as against the other. In a word, in all that he did, or attempted, he made it manifest that the one great and all commanding object with him, was the peace and preservation of the Union, and that this was the motive and main spring of all his measures. (FROM CHAPTER XII.: HOPE FOR THE NATION) - Frederick Douglass