Cobden on the complicity of the British people in supporting war (1852)

Found in: The Political Writings of Richard Cobden, vol. 2

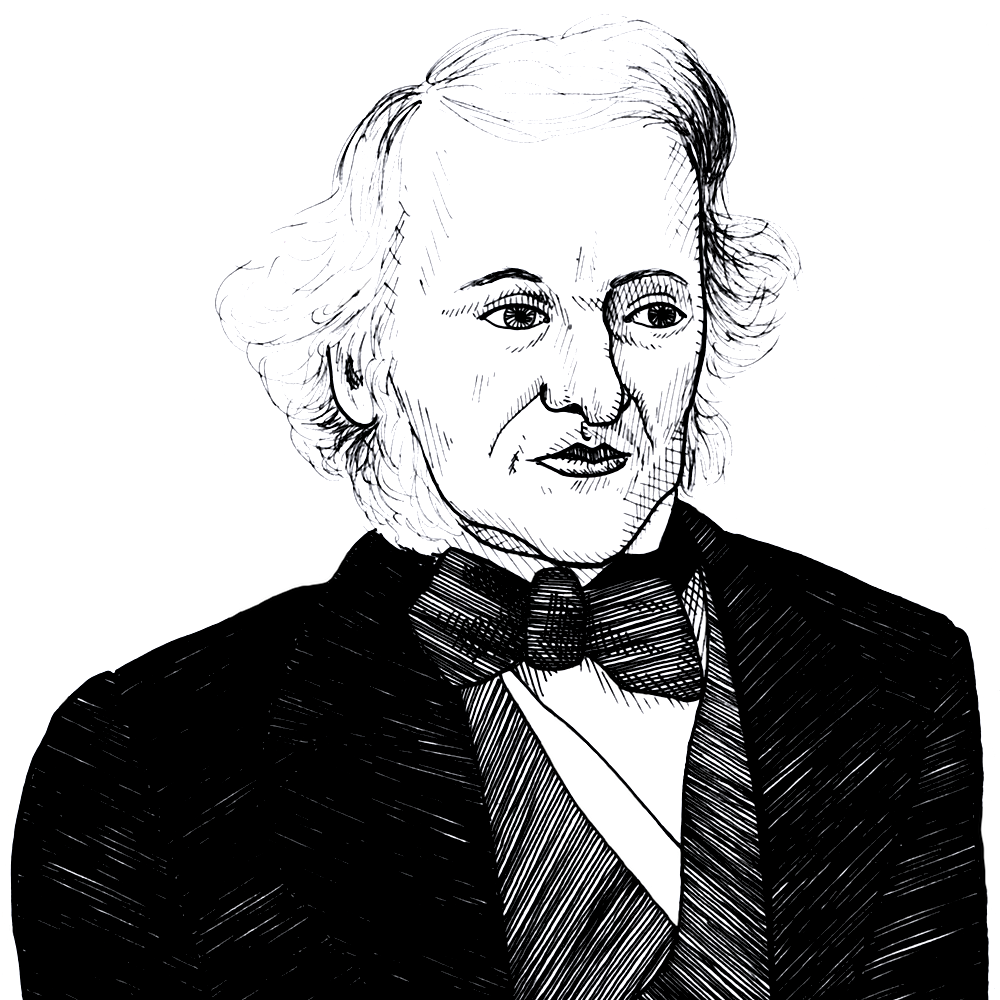

The peace and free trade advocate Richard Cobden (1804-1865) believed that before the “peace party” in Britain could be successful it had to overcome the popular misconception the British people had that they were a “peace-loving nation”:

War & Peace

But to rouse the conscience of the people in favour of peace, the whole truth must be told them of the part they have played in past wars. In every pursuit in which we embark, our energies carry us generally in advance of all competitors… It must be even so in the agitation of the peace party. They will never rouse the conscience of the people, so long as they allow them to indulge the comforting delusion that they have been a peace-loving nation. We have been the most combative and aggressive community that has existed since the days of the Roman dominion. Since the revolution of 1688 we have expended more than fifteen hundred millions of money upon wars, not one of which has been upon our own shores, or in defence of our hearths and homes. “For so it is,” says a not unfriendly foreign critic,∗ “other nations fight at or near their own territory: the English everywhere.” From the time of old Froissart, who, when he found himself on the English coast, exclaimed that he was among a people who “loved war better than peace, and where strangers were well received,” down to the day of our amiable and admiring visitor, the author of the Sketch Book, who, in his pleasant description of John Bull, has portrayed him as always fumbling for his cudgel whenever a quarrel arose among his neighbours, this pugnacious propensity has been invariably recognised by those who have studied our national character. It reveals itself in our historical favourites, in the popularity of the madcap Richard, Henry of Agincourt, the belligerent Chatham, and those monarchs and statesmen who have been most famous for their warlike achievements. It is displayed in our fondness for erecting monuments to warriors, even at the doors of our marts of commerce; in the frequent memorials of our battles, in the names of bridges, streets, and omnibuses; but above all in the display which public opinion tolerates in our metropolitan cathedral, whose walls are decorated with bas-reliefs of battle scenes, of storming of towns, and charges of bayonets, where horses and riders, ships, cannon and musketry, realise by turns, in a Christian temple, the fierce struggle of the siege and the battle-field.