Bentham on the liberty of contracts and lending money at interest (1787)

Found in: Defence of Usury

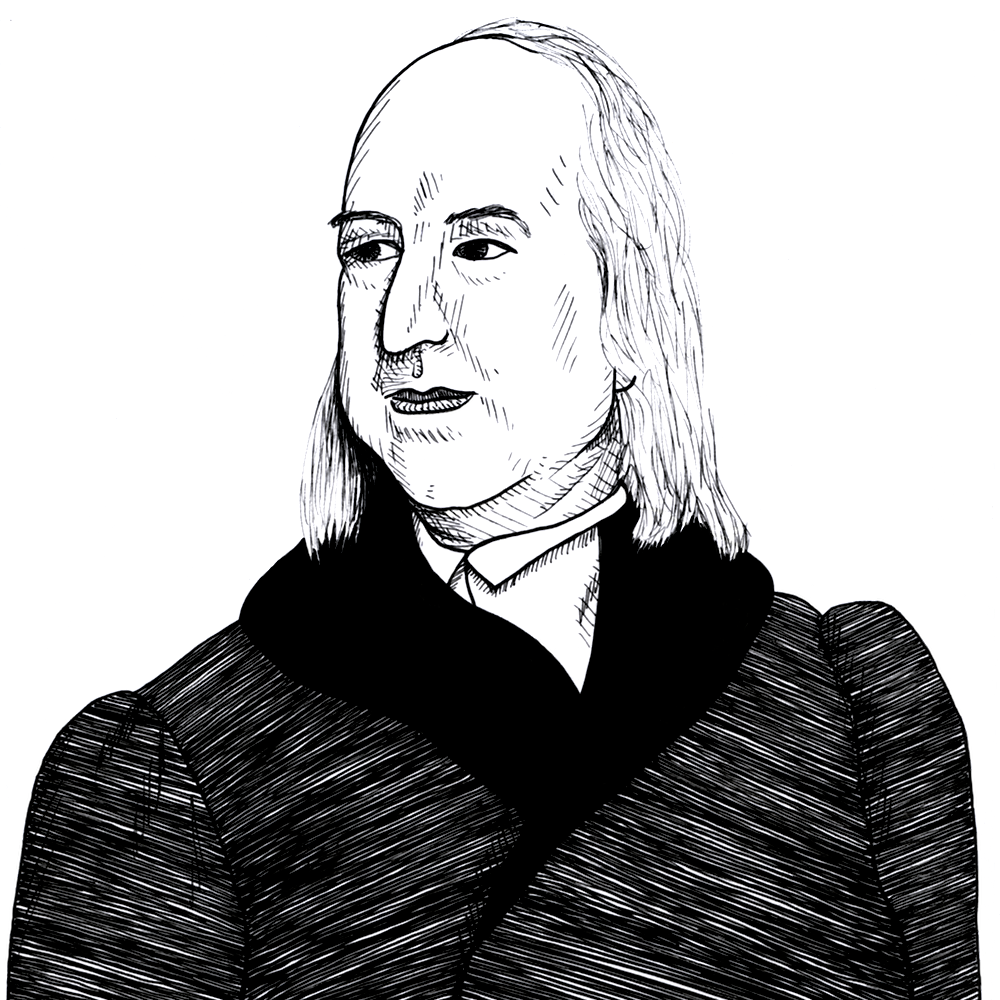

The English utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) defends the practice of lending money at interest (“usury”) as just another example of consenting adults engaging in their legal right to make contracts with each other:

Economics

Among the various species or modifications of liberty, of which on different occasions we have heard so much in England, I do not recollect ever seeing any thing yet offered in behalf of the liberty of making one’s own terms in money-bargains. From so general and universal a neglect, it is an old notion of mine, as you well know, that this meek and unassuming species of liberty has been suffering much injustice….

In a word, the proposition I have been accustomed to lay down to myself on this subject is the following one, viz. that no man of ripe years and of sound mind, acting freely, and with his eyes open, ought to be hindered, with a view to his advantage, from making such bargain, in the way of obtaining money, as he thinks fit: nor, (what is a necessary consequence) any body hindered from supplying him, upon any terms he thinks proper to accede to.