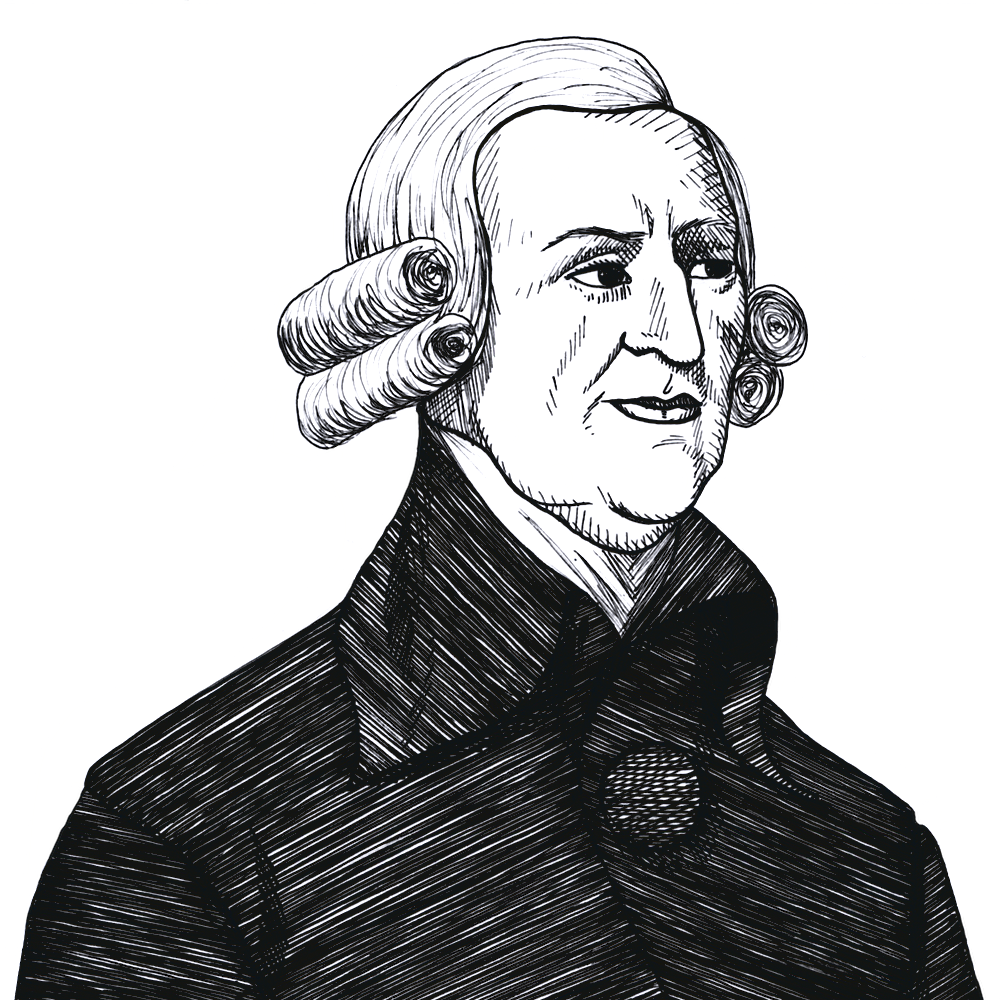

Adam Smith on why people obey and defer to their rulers (1759)

Found in: Theory of Moral Sentiments and Essays on Philosophical Subjects (1869)

In the Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) Adam Smith (1723-1790) reflects on why so many people defer to authority, especially to monarchs and the nobility:

Class

Even when the order of society seems to require that we should oppose them, we can hardly bring ourselves to do it. That kings are servants of the people, to be obeyed, resisted, deposed, or punished, as the public conveniency may require, is the doctrine of reason and philosophy; but it is not the doctrine of nature. Nature would teach us to submit to them for their own sake, to tremble and bow down before their exalted station, to regard their smile as a reward sufficient to compensate any services, and to dread their displeasure, though no other evil were to follow from it, as the severest of all mortifications. To treat them in any respect as men, to reason and dispute with them upon ordinary occasions, requires such resolution, that there are few men whose magnanimity can support them in it, unless they are likewise assisted by similarity and acquaintance.