Auberon Herbert, “Mr. Spencer and the Great Machine” (1906)

|

The Ruling Class and the State: An Anthology from the OLL Collection[See the Table of Contents of this Anthology as well as the more comprehensive collection The OLL Reader] |

Auberon Herbert, "Mr. Spencer and the Great Machine" (1906)

[Created: January 17, 2018]

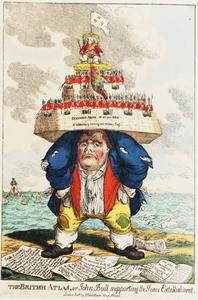

The image is James Gillray, "The British Atlas, or John Bull supporting the Peace Establishment" (1816). [See a higher resolution image and the illustrated essay on "James Gillray on War and Taxes during the War against Napoleon".

Source

Auberon Herbert, The Right and Wrong of Compulsion by the State, and Other Essays, ed. Eric Mack (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1978). </titles/591>.

- Essay Eight. Mr. Spencer and the Great Machine - Delivered as the Herbert Spencer Lecture at Oxford University on June 7, 1906, this paper was published by Oxford University Press in 1908 as part of The Voluntaryist Creed. </titles/591#lf0146_head_027>.

More about Auberon Herbert (1838-1906),

ESSAY EIGHT. MR. SPENCER AND THE GREAT MACHINE (June 7, 1906)

I began my lecture at Oxford by expressing my sense of the debt that we owed to Mr. Spencer for his splendid attempt to show us the great meanings that underlie all things—the order, the intelligibility, the coherence, that exist in this world of ours. I confessed that, on some great points of his philosophy, I differed from his teaching, parting, so to speak, at right angles from him; but that difference did not alter my view of how much he had helped us in the clear bold way in which he had traced the great principles running through the like and unlike things of our world; and in which with so skillful a hand he had grouped the facts round those principles, that he always followed—might I say—with the keen instinct of a hound that follows the scent of the prey in front of him. Time, I thought, might take away much, and might add much; but the effort to unite all parts of the great whole, to bind and connect them all together, would remain as a splendid monument of what one man, treading a path of his own, could achieve.

But today we are only concerned with his social and political teaching, where we may, I think, follow his leading with more reliance, and with but little reserve. I have often laughed and said that, as far as I myself was concerned, he spoiled my political life. I went into the House of Commons, as a young man, believing that we might do much for the people by a bolder and more unsparing use of the powers that belonged to the great lawmaking machine; and great, as it then seemed to me, were those still unexhausted resources of united national action on behalf of the common welfare. It was at that moment that I had the privilege of meeting Mr. Spencer, and the talk which we had—a talk that will always remain very memorable to me—set me busily to work to study his writings. As I read and thought over what he taught, a new window was opened in my mind. I lost my faith in the great machine; I saw that thinking and acting for others had always hindered, not helped, the real progress; that all forms of compulsion deadened the living forces in a nation; that every evil violently stamped out still persisted, almost always in a worse form, when driven out of sight, and festered under the surface. I no longer believed that the handful of us—however well-intentioned we might be—spending our nights in the House, could manufacture the life of a nation, could endow it out of hand with happiness, wisdom and prosperity, and clothe it in all the virtues. I began to see that we were only playing with an imaginary magician's wand; that the ambitious work we were trying to do lay far out of the reach of our hands, far, far, above the small measure of our strength. It was a work that could only be done in one way—not by gifts and doles of public money, not by making that most corrupting and demoralizing of all things, a common purse; not by restraints and compulsions of each other; not by seeking to move in a mass, obedient to the strongest forces of the moment, but by acting through the living energies of the free individuals left free to combine in their own way, in their own groups, finding their own experience, setting before themselves their own hopes and desires, aiming only at such ends as they truly shared in common, and ever as the foundation of it all, respecting deeply and religiously alike their own freedom, and the freedom of all others.

And if it was not in our power—we excellent and worthy people—fighting our nightly battle of words, with our half-light, our patchwork of knowledge, and our party passions, often swayed, in a great measure unconsciously, by our own interests, half autocrats, half puppets, if it was not given to us to create progress, in any true sense of the word, and to present it to the nation, ready-made, fresh from our ever-busy anvil, much in the fashion that kindhearted nurses hand out cake and jam to expectant children; if all this taking of a nation, ready-made, fresh from our ever-busy anvil, bewildered dream, a careless conceit on our part, might it not, on the other hand, be only too easily in our power to mislead and to injure, to hinder and destroy the voluntary self-helping efforts and experiments that were beyond all price, to depress the great qualities, to soften and break down the national fiber, and in the end, as we flung our gifts broadcast, to turn the whole people into two or three reckless quarreling crowds, that had lost all confidence in their own qualities and resources, that were content to remain dependent on what others did for them—ever disappointed, ever discontented, because the natural and healthy field of their own energies had been closed to them, and all that they now had to do was to clamor as loudly as possible for each new thing that their favorite speakers hung in glittering phrases before their eyes? I saw that no guiding, no limiting or moderating principle existed in the competition of politician against politician; but that almost all hearts were filled with the old corrupting desire, that had so long haunted the world for its ceaseless sorrow, to possess that evil mocking gift of power, and to use it in their own imagined interest—without question, without scruple—over their fellow-men.

From that day I gave myself to preaching, in my own small way, the saving doctrine of liberty, of self-ownership and self-guidance, and of resisting that lust for power, which had brought such countless sufferings and misfortunes on all races in the past, and which still, today, turns the men and women of the same country, who should be as friends and close allies, if the word “country” has any meaning, into two hostile armies, ever wastefully, uselessly, and to the destruction of their own happiness and prosperity, striving against each other, always dreading, often hating, those whom the fortunes of war may at any moment make their masters. Was it for this—this bitter, reckless and rather sordid warfare—I tried to ask, that we were leading this wonderful earthlife; was this the true end, the true fulfillment of all the great qualities and nobler ambitions that belonged to our nature?

Now, whether you judge that I acted rightly or wrongly in thus yielding myself to Mr. Spencer's influence, you will not, I think, quarrel very seriously with me, if I say that between Mr. Spencer's mind and the mind of the politician there lies the deepest of all gulfs; and that there is no region of human thought which is so disorderly, so confused, so lawless, so little under the rule of the great principles, as the region of political thought. It must be so, because that disorder and confusion are the inevitable consequence and penalty of the strife for power. You cannot serve two masters. You cannot devote yourself to the winning of power, and remain faithful to the great principles. The great principles, and the tactics of the political campaign, can never be made one, never be reconciled. In that region of mental and moral disorder, which we call political life, men must shape their thoughts and actions according to the circumstances of the hour, and in obedience to the tyrant necessity of defeating their rivals. When you strive for power, you may form a temporary, fleeting alliance with the great principles, if they happen to serve your purpose of the moment, but the hour soon comes, as the great conflict enters a new phase, when they will not only cease to be serviceable to you, but are likely to prove highly inconvenient and embarrassing. If you really mean to have and to hold power, you must sit lightly in your saddle, and make and remake your principles with the needs of each new day; for you are as much under the necessity of pleasing and attracting, as those who gain their livelihood in the street.

We all know that the course which our politicians of both parties will take, even in the near future, the wisest man cannot foresee. We all know that it will probably be a zigzag course; that it will have “sharp curves,” that it may be in self-evident contradiction to its own past; that although there are many honorable and high-minded men in both parties, the interest of the party, as a party, ever tends to be the supreme influence, overriding the scruples of the truer-judging, the wiser and more careful. Why must it be so, as things are today? Because this conflict for power over each other is altogether different in its nature to all other—more or less useful and stimulating—conflicts in which we engage in daily life. As soon as we place unlimited power in the hands of those who govern, the conflict which decides who is to possess the absolute sovereignty over us involves our deepest interests, involves all our rights over ourselves, all our relations to each other, all that we most deeply cherish, all that we have, all that we are in ourselves. It is a conflict of such supreme fateful importance, as we shall presently see in more detail, that once engaged in it we must win, whatever the cost; and we can hardly suffer anything, however great or good in itself, to stand between us and victory. In that conflict affecting all the supreme issues of life, neither you nor I, if we are on different sides, can afford to be beaten.

Think carefully what this conflict and what the possession of unlimited power in plainest matter of fact means. If I win, I can deal with you and yours as I please; you are my creature, my subject for experiment, my plastic material, to which I shall give any shape that I please; if you win, you in the same way can deal with me and mine, just as you please; I am your political plaything, “your chattel, your anything.” Ought we to wonder that, with so vast a stake flung down on the table, even good men forget and disregard all the restraints of their higher nature, and in the excitement of the great game become utterly unscrupulous? There are grim stories of men who have staked body and soul in the madness of their play; are we after all so much unlike them—we gamesters of the political table—staking all rights, all liberties, and the very ownership of ourselves? And what results, what must result from our consenting to enter into this reckless soul-destroying conflict for power over each other? Will there not necessarily be the ever-present the haunting, the maddening dread of how I shall deal with you if I win; and how you will deal with me if you win? That dread of each other, vague and undefined, yet very real, is perhaps the worst of all the counselors that men can admit to their hearts. A man who fears, no longer guides and controls himself; right and wrong become shadowy and indifferent to him; the grim phantom drives, and he betakes himself to the path—whatever it is—that seems to offer the best chance of safety. We see the same vague dread acting upon the nations. At times you may have an aggressive and ambitious government, planning a world policy for its own aggrandizement, that endangers the peace of all other nations; but in most cases it is the vague dread of what some other rival nation will do with its power that slowly leads up to those disastrous and desolating international conflicts. So it is with our political parties. We live dreading each other, and become the reckless slaves of that dread, losing conscience, losing guidance and definite purpose, in our desperate effort to escape from falling under the subjection of those whose thoughts and beliefs and aims are all opposed to our own. True it is that the leaders of a party may have their own higher desires, their own personal sense of right, but it is a higher desire and sense of right which they must often with a sigh—or without a sigh—put away into their pockets, bowing themselves before the ever-present necessity of winning the conflict and saving their own party from defeat. The stake is too great to allow room for scruples, or the more delicate balancings of what is right and wrong in itself.

Now let us look how that winning of the political battle has to be done. Winning means securing for our side the larger crowd; and that can only be done, as we know in our hearts, though we don't always put it into words, by clever baiting of the hook which is to catch the fish. It is of little use throwing the bare hook into the salmon pool; you must have the colors brightly and artistically blended—the colors that suit the particular pool, the state of the water, the state of the weather. Unless you are learned in the fisherman's art, it is but few fish you will carry home in your basket. So in the political pool you must skillfully combine all the glittering attractions that you have to offer, you must appeal to all the different special interests, using the well-chosen lure for each. It is true that there may be exceptional moments with all nations when the political arts lose much of their importance, when some great matter rises above special interests, and the people also rise above themselves. But that is human nature at its best; and not the human nature as we have to deal with it on most days of the week. It is also true that the best men in every party stoop unwillingly; but, as I have said, they are not their own masters; they are acting under forces which decide for them the course they must follow, and reduce to silence the voice within them. They have gone in for the winning of power, and those who play for that stake must accept the conditions of the game. You can't make resolutions—it is said—with rose water; and you can't play at politics, and at the same time listen to what your soul has to say in the matter. The soul of a high-minded man is one thing; and the great game of politics is another thing. You are now part of a machine with a purpose of its own—not the purpose of serving the fixed and supreme principles—the great game laughs at all things that stand before and above itself, and brushes them scornfully aside, but the purpose of securing victory; and to that purpose all the more scrupulous men must conform, like the weaker brethren, or—as the noblest men do occasionally—stand aside. As our system works, it is the party interests that rule and compel us to do their bidding. It must be so; for without unity in the party there is no victory, and without victory no power to be enjoyed. When once we have taken our place in the great game, all choice as regards ourselves is at an end. We must win; and we must do the things which mean winning, even if those things are not very beautiful in themselves.

And what is it that we have to do? In plain words—and plainness of thought, directness of speech, is the only wholesome course—we must buy the larger half of the nation; and buying the nation means setting up before all the various groups, of which it is composed, the supreme object, the idol of their own special interests. We must offer something that makes it worthwhile for each group to give us their support, and that something must be more than our rivals offer. “Put your own self-interests in the first place, and see that you get them,” is the watchword of all politics, though we don't often express it in those crude and unashamed terms. Political art has, like many another accomplishment, its own refinements for half veiling the real meanings. If we wish to do our work in the finer fashion, in the artist's way, we must use the light and skillful hand; we must mix in the attractive phrases, appeal to patriotic motives, borrow, a little cautiously, such assistance as we can from the great principles—a slight passing bow that does not too deeply commit us to their acquaintance as regards the future—and throw dexterously over it all, as a clever cook introduces into her dishes her choicest seasoning, a flavor of noble and disinterested purpose. It is a fine art of its own, to buy, and at the same time to gild and beautify the buying; to get the voter into the net, and at the same time to inspire him with the happy consciousness that, while he is getting what he wants, he is through it all the devoted patriot, serving the great interests of his country.

And then also you must study and understand human nature; you must play, as the skilled musician plays on his instrument, on all the strings, both the higher and lower, of that nature; you must utilize all ambitions, desires, prejudices, passions and hatreds—lightly touching, as occasion offers, on the higher notes. But in this matter, as in all other matters, underneath the fine words, business remains business; and the business of politics is to get the votes, without which the great prize of power could not by any possibility be won. Votes must be had—the votes of the crowd, both the rich and the poor crowd, whatever may be the price which the market of the day exacts from those who are determined to win.

II

So rolls the ball. We follow the inevitable course that seeking for power forces upon us. Politics, in spite of all better desires and motives, become a matter of traffic and bargaining; and in the rude process of buying, we find ourselves treading not only on the interests, but on the rights of others, and we soon learn to look on it as a quite natural and unavoidable part of the great game. Keener and keener grows the competition, more heart-and brain-absorbing grows the great conflict, and the people and the politicians cannot help mutually corrupting each other. This buying up of the groups is so distinctly recognized nowadays, that lately a Times correspondent—whose letters we read with much interest—speaking of a newly formed ministry abroad, wrote, with unconscious cynicism, that it would have to choose between leaning on the extreme right or the extreme left.

What then, you may say, are we to believe; that the whole body of those concerned with politics—in which class we almost all in our degree are included—are selfish and corrupt, utterly disregarding and despising the just claims of each other? I hope things are not quite so bad as that. Human nature is a mixed thing, and many of us contrive to think in the nobler way and the smaller way at the same time. There is at least one excuse that may be pleaded for us all. What happens here—as happens in so many other cases—is that carelessly and without reflection we place ourselves under an untrue, a demoralizing and wrong system, that fatally blinds and misleads us, lowers and blunts the better part of our nature, and almost compels us, by the force that it exerts, to follow crooked paths and do wrong things. I have not time to illustrate this simple truth of the sacrifice of character to system; but let me take one instance of the injury that results, whenever we lose our own self-guidance under a system, that is wrong in itself, and, as a wrong system so often is apt to be, despotic in its nature.

I think many of us see the existence of this injury as regards character, when we watch that part of fashionable society which makes of organized pleasure-hunting the first occupation—I might almost say the duty—of life. Here also people construct a system which overpowers their individual sense of what is right and useful and fitting; they submit themselves to the tyrannous rule of follies of different kinds, as if they had no judgment, no discriminating sense of their own, and as a consequence become as a mere race of butterflies, losing the higher sense of things, and wasting their lives.

In all such instances, where lies the remedy? I think both Mr. Spencer and Mr. Mill would have made the same answer—you can only mend matters by individualizing the individual. It is of little use preaching against any hurtful system, until you go to the heart of the matter, until you restore the individual to himself, until you awaken in him his own perceptions, his own judgment of things, his own sense of right, until you allow what Mr. Spencer called his own apparatus of motive—and not an apparatus constructed for him by others—to act freely upon him, an apparatus that tends sooner or later to work to the better things; and so detach him from his crowd, which whirls him along helplessly, wherever it goes, as the stream carries its unresisting bubbles along with it. There lies the great secret of the whole matter. We have as individuals to be above every system in which we take our place, not beneath it, not under its feet, and at its mercy; to use it, and not to be used by it; and that can only be when we cease to be bubbles, cease to leave the direction of ourselves to the crowd—whatever crowd it is, social, religious, or political—in which we so often allow our better selves to be submerged.

It was for this individualizing of the individual that both Mr. Spencer and Mr. Mill pleaded so powerfully; only in the free individual, self-restraining, self-guiding, that they saw, I think, the hope of true permanent good. They saw that nobody yet has ever been saved, in the best sense, or ever will be saved by vast systems of machinery; Mr. Mill, perhaps, especially looking from the moral point of view, and Mr. Spencer contrasting the intellectual and material consequences of the two opposed systems—self-guidance, and guidance by others.

And here, perhaps, I ought to add a few words. While we lay the heaviest share of blame upon the political system that takes possession of us, and leaves little room for self-guidance, are we to lay no direct blame upon ourselves, for being content to take our place in the system, that few, I think, in calm moments of reflection, can fully justify to their own hearts? Let us be completely frank in this great matter. Is the system of giving away power over ourselves, or seeking to possess it over others, in itself right or wrong? If it is wrong, don't let us make excuses for acquiescing in it; don't let us sigh and feebly wring our hands, confessing the faults and dangers, but pleading that we see no other way before us. Where there is a bad way, there is also a good way, if men once resolutely set themselves to find it.

But you may, perhaps, doubt if the system is wrong in itself; if it is not merely perverted and turned from its true purpose by our human weaknesses. You may be inclined to plead: “It is true that politicians must suppress a part of their own opinions; it is true that there is a sort of bargaining that goes on among the groups, that in order to gain their own special end, they have to act with other groups—groups which may differ strongly from themselves on some important points; it is true also that the leaders of a party must take all these groups into their calculations and, as our American friends say, placate the interests; but there is not necessarily anything corrupt in such action on the part of either the groups or the politicians, or their leaders, at least so long as we can fairly credit them all with desiring the common good, at the same time as they pursue their own special interests, and doing the best that the situation allows alike for these two ends; even if these ends may occasionally diverge somewhat from each other.

“Of course we admit that men may be easily tempted to overstep the just and true line, may be tempted in the rivalry of parties, in the strife for power, in the desire to seize the glittering prize, to forget for a while the common good, to push it back into the second place, to be overkeen about their own interests; no doubt the possession of power has its dangers, and tempts many men to say and do what we cannot defend; but we must trust to the general better and wiser feeling of the whole people, or of the whole party, to hold in check these aberrations of some of the fighters, and to strike the balance fairly between the two influences. We must remember that all action in common demands some sacrifices; has its disabilities, as well as its great advantages. We cannot act together, unless there is a considerable, sometimes a large, suppression of our own selves. We must accept that bit of necessary discipline; we must be prepared to keep step with the marching (or ought you to say the maneuvering) regiment, if we are to achieve anything by united action, and not to remain as separate sticks, that no bond holds together. All through life the same principle runs. In every club, society, joint-stock undertaking, we submit to guidance; we give up a part of our views and desires to gain the more important object. Yet when we do so, nobody accuses us of sacrificing our own guiding sense, or of being corrupt, or of entering into a hurtful and dangerous traffic.”

Yes, I should reply, but in all these voluntary associations you retain your own free choice; you can enter into them or leave them, as you think right; and that free choice in all these cases is the saving element. But I ought to ask pardon of our friend, the apologist, for interrupting him.

“Even if our political system” (it is our friend who is again speaking) “has its defects—grave defects if you like—still after all, it is the instrument of progress, and we know of no other to take its place. Surely it is more profitable to try to mend its faults than to quarrel with the whole thing, for which we can see no substitute.”

That, I think, is a fair representation of the way in which many of us look at political life, a way that perhaps supplies us with some momentary consolation, when our minds are troubled with what we see passing before us; but how far, if we try to see quite clearly, can we accept such reasoning, as giving any real answer to the graver doubts and hesitations? Is it not only a bit of agreeable sticking plaster, laid over the sore place, an opiate-like soothing of troubled consciences, hardly intended seriously to touch the deeper part of the matter? Let us now try to look frankly beneath the surface, and do our best to see what is the true nature of the system in which we so easily acquiesce.

What does representative government mean? It means the rule of the majority and the subjection of the minority; the rule of every three men out of five, and the subjection of every two men. It means that all rights go to the three men, no rights to the two men. The lives and fortunes, the actions, the faculties and property of the two men, in some cases their beliefs and thoughts, so far as these last can be brought within the control of machinery, are all vested in the three men, as long as they can maintain themselves in power. The three men represent the conquering race, and the two men—vae victis as of old—the conquered race. As citizens, the two men are decitizenized; they have lost all share for the time in the possession of their country, they have no recognized part in the guidance of its fortunes; as individuals they are deindividualized, and hold all their rights, if rights they have, on sufferance. The ownership of their bodies, and the ownership of their minds and souls—so far as you can transfer by machinery the ownership of mind and soul from the rightful owners to the wrongful owners—no more belongs to them, but belongs to those who hold the position of the conquering race.

Now, that is, I believe, a true and uncolored description of the system, as it is in its nakedness, as it is in its real self, under which we are content to live. It is not an exaggerated description—there is not a touch in the picture with which you can fairly quarrel. It is true that the real logic of the system does not yet prevail. It is true that a certain number of things may for a time modify and restrain the final triumphs of the majority. In some parliamentary countries, the majority tends to be more composite in its character than with us, and therefore tumbles more easily to pieces. On the other hand, with us at least, whatever it may be in some other countries that have parliaments, minorities may rend the air and reach the skies, if they can, with their cries and complaints, and so to a certain extent may raise difficulties—a method of warfare in which all minorities grow more or less skillful by practice—in the path of the majority; with us also there still exists happily a friendlier, more genial spirit between all parts of the people than prevails in other countries. Thanks to the fact that the great serpent of bureaucracy holds us as yet less closely in its folds; thanks to the still lingering traditions of self-help and voluntary work; thanks to the good humor and love of fair play, which is to some extent nursed by our fellowship in the same games that all classes love—games that I think have redeemed some part of the politician's mistakes—the rule of the majority is with us as yet more tempered, less violent and unscrupulous, than it is in some other countries; but give their full weight to all these modifying influences, which as yet restrain our system of the conquering and the conquered races from finding its full development—still they do not alter the main, the essential fact, that we are content to live under a system that vests the rights of citizenship, the share in the common country, the ownership of body, faculties, and property, and to some extent, the ownership of mind and soul, of, say, two-fifths of the nation in the hands of the three-fifths. Such is the system in which we think it right and self-respecting to acquiesce—a system which, in the case of every two men out of five, wipes out at a stroke, so far as the duties of citizenship are concerned, and even to a large extent as regards their personal relations, all the higher part of their nature, their judgment, conscience, will—treating them as degraded criminals, who, for some unrecorded offense have deserved to forfeit all the great natural rights, and to lose their true rank as men. They tell us that nowadays men are not punished for their opinions. They succeed in forgetting, I suppose, the case of every two men out five.

Plead then, if you like, on behalf of such a system all the expediencies of the moment, all the conveniences that belong to power, all the pressing things you desire to do through its machinery, plead objects of patriotism, plead objects of philanthropy; yet are you right for the sake of these things, excellent as they may be in themselves, to acquiesce in that which—when stripped bare to its real, its lowest terms, is—the words are not too harsh—the turning of one part of the nation into those who own their slaves, and the other part into the slaves who are owned?

You may say, as a friend of mine says, “I feel neither like a slave owner nor like a slave,” but his feelings, however admirable in themselves, do not alter the system, in which he consents to take part, of trying to obtain control over his fellow-men; and, if he fails, in acquiescing in their control over himself. He may never wish or mean to exercise unfairly the power in which he believes, should it fall into his hands; but can he answer for himself in the great crowd, in which he will count for such a minute fractional part, for what they will do, or where they will go?

III

My friend is quite aware, I think, that power is a rather dangerous thing to handle; but he will handle it with good sense, in the spirit of moderation and fairness, he will not suffer himself to let go of the great principles; he will not cross the boundary line that divides the rightful from the wrongful use. Well, moderation, and fairness, and good sense are excellent things, not in this matter alone, but in all matters. And so are the great principles; that is to say, if you see them in all clearness and are determined to follow them. But the saving power of the great principles depends upon how far we loyally and consistently accept them. They can be of little real help and guidance to us if we play and trifle with them, accepting them today, and leaving them on one side tomorrow, making them conform, as occasion arises, to our desires and ambitions, and then lightly finding excuses for deserting them whenever we find them inconvenient. Let us once more be quite frank. When we talk of fairness and moderation and good sense, as constituting our defense against the abuse of unlimited power, are we not living in the region of words—using convenient phrases, as we so often do, to smooth over and justify some course which we desire to take, but about which in our hearts we feel uncomfortable misgivings? Let us by all means cultivate as much fairness and moderation as possible—they will always be useful—but don't let our trust in these good things lead us away from the question that, like the Sphinx's riddle, must be answered under penalties from which there is no escape: Is unlimited power, whether with or without good sense and fairness, a right or wrong thing in itself? Can we in any way make it square with the great principles? Can we morally justify the putting of the larger part of our mind and body—in some cases almost the whole—under the rule of others; or the subjecting of others in the same way to ourselves?

If you answer that it is a right thing, then see plainly what follows. You are putting the force of the most numerous, or perhaps of the most cunning, who often lead the most numerous—which, disguise and polish the external form of it as much as you like, will always remain true to its own essentially brutal and selfish nature—in the first place, making of it our supreme principle; and if unlimited power—remember it is unlimited power; power to do whatever the governing majority thinks right—is a right thing, must you not leave it, whatever may be your own personal views, to those who possess it to decide how they will employ it? You can't dictate to others, in the hour of their victory, as to what they will do or not do; and they can't dictate to you, in the hour of your victory. Unlimited power, as the term expresses, can only be defined and limited by itself; if it were subject to any limiting principle, it would cease to be unlimited, and become something of a different nature.

And remember always—when once you entered into the struggle for the possession of this unlimited power—that you sanctioned its existence, as a lawful prize, for which we may all rightly contend; and if the prize does not fall to you, it will only remain for you to accept the consequences of your consent to take part in the reckless and dangerous competition. By entering into that conflict, by competing for that prize, you sanctioned the ownership of some men by other men; you sanctioned the taking away from some men—say two-fifths of the nation—all the great rights, and the reducing of them to mere ciphers, who have lost power over themselves.

Once you have sanctioned the act of stripping the individual of his own intelligence and will and conscience, and of the self-guidance which depends upon these things, you cannot then turn your back upon yourself, and indignantly point to the mass of unhappy individuals who are now writhing under the stripping process. You should have thought of all this before you consented to put up the ownership of the individual to public auction, before you consented to throw all these rights into the great melting pot. In your desire to have power in your own hands, you threw away all restraints, all safeguards, all limits as regards the using of it; you wanted to be able to do just as you yourself pleased with it, when once you possessed it; and what good reason have you now to complain, when your rivals—or shall I say your conquerors—in their turn do just what they please with it? You entered into the game with all its possible penalties; you made your bed, it only remains for you to lie on it.

Let us follow a little further this rightfulness of unlimited power in which you believe. If it is a right thing in itself, who shall give any clear and certain rule to tell us when and where it ceases to be a right thing? Is any right thing by being pushed a little further, and then a little further, and yet a little further, transformed at some definite point into a wrong thing, unless some new element, that changes its nature, comes into the matter? The question of degree can hardly change right into wrong in any authoritative way, that men with their many varying opinions will agree to accept. We may, and should forever dispute over such movable boundary lines—lines that each man according to his own views and feeling would draw for himself.

If it is right to use unlimited power to take the one-tenth of a man's property, is it also right to take one-half or the whole? If it is not right to take the half, where is the magical undiscoverable point at which right is suddenly converted into wrong? If it is right to restrict a man's faculties (not employed for an act of aggression against his neighbor) in one direction, is it right to restrict them in half a dozen or a dozen different directions? Who shall say? It is a matter of opinion, taste, feeling. Perhaps you answer, we will judge each case on its merits; but then once more you are in the illusory region of words, for, apart from any fixed principle, the merits will be always determined by our varying personal inclinations. It is all slope, ever falling away into slope, with no firm level standing place to be found anywhere.

Nor do I feel quite sure, if we speak the truth, that any of us are much inclined to accept the rule of moderation and good sense in this matter. You and I, who have entered into this great struggle for unlimited power, have made great efforts and sacrifices to obtain it; now that we have won our prize, why should we not reap the full fruits of victory; why should we be sparing and moderate in our use of it? Is not the laborer worthy of his wage; is not the soldier to receive his prize money? If power was worth winning, it must be worth using. If power is a good thing, why should we hold back our hand; why not do all we can with it, and extract from it its full service and usefulness? Our efforts, our sacrifices of time, money and labor, and perhaps of principle—if that is worth counting—were not made for the possession of mere fragmentary pieces of power, but for power to do exactly as we please with our fellow-men. It is rather late in the day, now that we have won the stake, to tell us that we must leave the larger part of it lying on the table; that, having defeated the enemy, we must evacuate his territory, and not even ask for an indemnity to compensate us for our sacrifices. If power, as an instrument, is good in itself, now that we hold it in our hand, why break its point and blunt its edge?

And then what about the great principles, which my friend does not propose exactly to follow, but on which at all events he will be good enough to keep a watchful eye? Where are they? What are they? What great principle remains, when you have sanctioned unlimited power? You can't appeal to any of the great rights—as rights; the rights of self-ownership and self-guidance, the rights of the free exercise of faculties, the rights of thought and conscience, the rights of property, they are no longer the recognized and accepted rules of human actions; they are now reduced to mere expediencies, to which each man will assign such moderate value as he chooses. You are now out in the great wilderness, far away from all landmarks. Around the throne of unlimited power stretches the vast solitude of an empty desert. Nothing can be fixed or authoritative in its presence; by the fact of its existence, by the conditions of its nature, it becomes the one supreme thing, acknowledging—except perhaps occasionally in courtly phrases for soothing purposes—nothing above itself, writing its own ethics, interpreting its own necessities, making of its own safety and continuance the highest law, and contemptuously dismissing all other discrowned rivals from its presence.

Now turn from the discussion of the moral basis of unlimited power to the practical working of our power systems. There is I think one blessed fact that runs through all life—that if a thing is wrong in itself, it won't work. No skill, no ingenuity, no elaborate combinations of machinery, will make it work. No amount of human artifice and contrivance, no alliance with force, no reserves of guns and bayonets, no nation in arms even if almost countless in number, can make it work. So is it with our systems of power. They don't work and they can't work. In no real sense, can you, as the autocrat, govern men; in no real sense, can the people imitate the autocrat and govern each other. The government of men by men is an illusion, an unreality, a mere semblance, that mocks alike the autocrat and the crowd that attempt to imitate him. We think in our amazing insolence that we can deprive our fellow-men of their intelligence, their will, their conscience; we think we can take their soul into our own keeping; but there is no machinery yet discovered by which we can do what seems to us so small and easy a matter. We think that the autocrat governs his slaves, but the autocrat himself is only one slave the more amongst the crowd of other slaves. In the first place he himself is governed by his own vast machinery; helpless he stands—one of the pitiable objects in this world of ours—in the midst of the countless wheels which he can set in motion, but which other forces direct; and then even the wheels have souls of their own, though not perhaps very beautiful ones, and ever likely to go a persistent and obstinate way of their own. But what is of deeper consequence is that his government is silently conditioned by the slaves themselves.

Sunk in their darkness, helpless, inarticulate, they may be; yet for all that they in their turn are slave owners as well as slaves, as always happens wherever you build up these great fabrics of power. While the slaves obey, they also, though they utter no word, in their turn command. If the autocrat disregards that silent voice, disregards the unspoken conditions that they impose upon him, then in its own due time comes the great crash, and his power passes from him, a broken and miserable wreck. You may crush and hold in subjection for a time the external part of men, but you cannot govern and possess their soul. Their soul lies out of your reach, and is in its nature as ungovernable as the wind or the wave. You may trick and deceive it for a time; you may make it the instrument of its own slavery by cleverly arranged systems of conscription, and other governing devices; you may cast it into a deep sleep, but sooner or later it wakes, and rebels, and claims its own inheritance in itself.

In the same way there is no such thing as what is called the self-government of a nation. How can you get self-government by turning one half of a nation into a secondhand copy of a tsar? That, as Mill showed long ago, is not self-government; but government by others. It is true that here, as with the autocrat, a majority can for a season use for its own ends and oppress a minority, can do with it what in its heart it lusts to do, can make it the corpus vile of its experiments, can make of it a drawer of water and hewer of wood; but it is only for a short day. Here again that uncompromising thing, the soul, stands in the way, and refuses to be transferred from the rightful to the wrongful owner. The power of the majority wanes, and the power of the minority grows, and the oppressor and the oppressed change places.

But apart from all the deeper reasons that make the subjection of men by men impossible, was there ever such a hopeless, I might say absurd, bit of machinery, only to be compared to a child's attempt to put together a wooden clock out of the chippings left in the wood basket, as the thing which we call a representative system? Invent all the ingenious plans that you like, but by no possibility can you represent a nation for governing purposes. The whole thing is a mere phrase.

Let us see what actually happens. Suppose a nation with 5,000,000 voters—2,000,000 voting on one side, and 3,000,000 on the other. In such a case we start with the astounding, the absurd, the grotesque fact that there is no attempt made to represent the 2,000,000. Even if you had a system of minority representation, it might possibly serve in some small measure to soothe the feelings of the subject race; it would not alter the hard fact of their subjection. But at present the 2,000,000 voters find no place of any kind in our calculations; they are simply swept off the board, not counted. That is the first remarkable feature of the representative system; and that, as you will admit, is not the happiest beginning with which to start. If representation constitutes the moral basis of power, then the fact that out of every five men two should be left unrepresented, requires a good deal of explanation; two-fifths of the moral basis at all events are wholly wanting. We are fond of talking of our representative system as if it rested on a democratic foundation; but under which of the three great democratic principles—equality, fraternity, liberty—does the sweeping off the board of two-fifths of the nation, the two men out of every five, find its sanction?

Let us, however, for the present leave the 2,000,000 voters to their fate. They are, as we have seen, only a subject race; and subject races must be duly reasonable, and not expect too great a share in the privileges of conquering races. Now let us turn to the case of the happy triumphant 3,000,000 voters, who hold in subjection the 2,000,000 voters. Are they themselves represented in any true sense? Let us see what happens to them—the majority, who are good enough for a time to take charge of all of us. Unlimited power means that our lords and masters of the moment may deal, that they will probably try to deal, with every, or almost every field of human activity. If there are, say, ten great state departments, such as trade, foreign affairs, local government, home government, and the rest; and if we suppose with due moderation that there are ten great questions connected with each of these departments, that may at any moment occupy the attention of our presiding majority, then we have a grand total of a hundred questions, upon which the opinions of the 3,000,000 electors will have to be represented. But alas! for our unfortunate and inconvenient human differences; how can the victorious 3,000,000 be represented on these hundred questions, when, if they think at all, they will all think more or less differently from each other? To express fully their many differences, they ought to have nearly 3,000,000 representatives; but we will not ask for perfection; so let us divide the number by a hundred and say 30,000 representatives—an arrangement which, if the representatives met and talked for twenty hours every day in the year, would give, let us say, something over eight seconds of talking time for each representatives during the course of the year as regards each of the hundred questions. When they had each talked their eight or nine seconds, how much real agreement should you expect to find among our 30,000 representatives on their hundred questions?

Place twenty men in a room to discuss one subject; and how many different opinions will you collect at the end, if the twenty men are intelligent, and interested in the subject? Will you not probably find three or four groups of opinions, each group representing a more or less different view? Now bring the 30,000 representatives together, and require them to agree, not on one subject, but on a hundred important and often complicated subjects. Remember they must agree—they have no choice—that necessity of agreement overrides everything else, for otherwise they cannot act together. But then comes the question—what is their agreement, forced upon them by the practical necessity of acting together as one man, morally worth? Is it not a mere form, a mere mockery, a mere illusion? They must agree; and they do agree; for the continuance of the party system, the winning of power, the subjecting of their rivals—all this depends on their agreeing; but in what sort of fashion, by what kind of mental legerdemain, is their agreement reached? It can only be reached in one simple way—by a wholesale system of self-effacement. The 30,000 individuals must be content on, say, ninety-five percent of the hundred questions, to have no opinions; or if they have opinions, to swallow ninety-five percent of their opinions at a gulp, and to play the convenient, if somewhat inglorious part of ciphers. Yet under our system it is this larger half of the nation, these 3,000,000 voters, who have undertaken the responsibility of thinking and acting for the nation, of deciding these hundred questions both for themselves and for the rest of us; and the only way of deciding left to them is to efface themselves, and have no opinions—a rather sad anticlimax, I am afraid, to some of our everyday rhetoric on the subject of representative systems.

If we look closely we find that these systems only mean that if we have no personal opinions, we can be represented, so far as it is possible or worthwhile to represent blank sheets of paper; if we have personal opinions, we can't be represented. The question then forces itself upon us, is it a bit of honest work, is it profitable, is it worth the trouble, to construct a huge machinery for the purpose of representing ciphers, who have no opinions; and when we have constructed our illusory, our make-believe machine, to go into the marketplace, and therefrom deliver ourselves of speeches about the excellence of our self-governing system? Is it right and true to set up a moral responsibility on the part of those who profess to govern, that cannot by any possibility be turned into a reality; to ask half the nation to sit in the seat of universal judgment, there to take their part in what is and must be an only half disguised farce? Does it not tell us something of the true nature of power, when we find ourselves obliged to descend to tricks of this kind in order to possess and to use it?

Does it mend matters to say that under our system we choose the best man available, and leave the hundred questions for him to deal with? That is only our old friend, the autocrat, come back once more, with a democratic polish rubbed over his face to disguise and, as far as may be, to beautify his appearance. Our sin consists in the suppression of our own selves and our own opinions; and in one sense we fall lower than the slaves of the autocrat, for they are simply sinned against, but we take an active part in the sin against ourselves.

And now how does this suppression of ourselves come about? There must be some powerful motive acting upon us, to induce us to take our place cheerfully in such a poor sort of comedy. Men don't suppress themselves, except to gain something that they much desire. Let us be frank once more, and confess we are bribed into this self-suppression by our reckless desire for power, and our desire to use the power, when gained, for special interests of our own. The power that we seek to win is a hard taskmaster as regards its conditions, and exacts that humiliating price from us. We take our own bribe for giving up our opinions, and play the part of ciphers, and at the same time bribe those others who are to play their part with us; we ask no questions of our conscience, but go on to the political exchange, and there with a light heart do the necessary selling and buying.

Now follow a little further this process of self-suppression, this process of making the ciphers. When you have once required of men to efface themselves and all the higher part of themselves, in order that they may act together, then follows that bargaining and juggling with the groups, of which I have already spoken. The disinterested opinions—ninety-five percent of them, as we calculated—have vanished, much in the same fashion as the 2,000,000 voters vanished; they are swept off the board, as things for which no place can be found, but which are only very much in the way of the real business in hand; and only a few leading self-interests—three or four perhaps—still remain. Now you may bind unbought men together, in the one and true way, by their opinions; but when they have no opinions, you must find a cement of a coarser and more material kind. Having once turned men into ciphers, nothing remains but to treat them as ciphers. The great trick, the winning of power, requires ciphers, and can't be played in any other fashion. Having once turned men into ciphers, you must appeal to them as good loyal party followers; or you must appeal to them as likely to get more from you than from any other buyer in the market: you can't appeal to them, except in the imaginative moments when you are treading the flowery paths of rhetoric, as men, possessed of conscience, and will, and responsibility, for in that case they might once more regain possession of their suppressed consciences and their higher faculties, and begin to think and judge for themselves—a result that would have very inconvenient consequences; for then they would no longer agree to have one opinion on the hundred subjects; they would divide and scatter themselves in all sorts of directions; they would be a source of infinite trouble and vexation to the distracted party managers; they would no longer be of use as fighting material; and the well-disciplined army would dissolve into an infinite number of separate and divergent fragments.

No! As long as party faces party, and the great struggle for power goes on, the rank and file, however intelligent, however well-educated, must be content to think with the party. They can't think for themselves, for if they did they would think differently; and if they thought differently, they could not act together; so they must be content to be just war material, very like the masses of conscripts which foreign governments occasionally employ to hurl against each other. If they were anything else, it would be a very poor fighting show that our political parties would make on their battlefield. The great struggle for power would die out, would come naturally to its end, when the suppression of self and the making of the ciphers had ceased to be.

It is well to notice here that in some other countries you have not two political parties of the same definite character as with us, but a large number of groups. The fact of the groups very slightly affects the situation. Under every system the vices that go with the seeking for power return in pretty nearly the same form. The groups can't form a majority, and obtain power, unless they amalgamate; which means that each group has its market price, makes the best bargain that it can for itself, and for the sake of that bargain consents to act with, and so to increase the strength and influence of those with whom it may be in strong disagreement. Of course hopeless moral confusion arises from this temporary amalgamation of the odds and evens, and separate, unlike pieces, from this making of a common cause by those who mean different things, and are almost as much opposed to each other as they are to the common enemy, to whom for the moment they are opposed.

Under no circumstances can we afford to depart from the great principle that we must never abandon our own personality, that we must only strive for the ends in which we ourselves believe, and never consent to enter into combinations, in which we either are used against our convictions, or use others against their convictions. Whenever we descend to “logrolling”—your services to pay for my services—we are lost in a sea of intrigue and corruption, and all true guidance disappears. There is no true guidance for any of us, except in our own best and highest selves, in our own personal sense of what is true and right. When that goes, there is little, if anything, worth the saving.

And now, passing by many incidents in the working of the great machine, that is so largely indulgent to our fighting and bargaining propensities, I come to what seems to me the very heart of Mr. Spencer's social and political teaching. It is not often given to a man to sum up in three words a great truth, that is fated sooner or later to revolutionize the thought and action of all nations; and yet that is, I think, what Mr. Spencer happily achieved. The three words were, progress is difference—that is, if you or I are to think more clearly, or to act more efficiently and more rightly than those who have preceded us, it can only be because at some point we leave the path which they followed, and enter a new path of our own; in other words, we must have the temper and courage to differ from accepted standards of thought and perception and action. If we are to improve in any direction, we must not be bound up with each other in inseparable bundles, we must have the power in ourselves to find and to take the new path of our own. Is not every improvement of machinery and method, every gain made in science and art, every choosing of the truer road and turning away from the false road that we have hitherto trodden—does it not all arise from those differences of thought and perception which, so long as freedom exists, even in its present imperfect forms, are from time to time born amongst us? Whenever men become merely copies and echoes of each other, when they act and think according to fixed and sealed patterns, is not all growth arrested, all bettering of the world made difficult, if not impossible? What hope of real progress, when difference has almost ceased to exist; when men think in the same fashion as a regiment marches; and no mind feels the life-giving stimulating impulse which the varying competing thoughts of others brings with it?

Do we not see in some parts of the East, when men are bound rigidly together under one system of thought, how difficult, how painful, the next upward step becomes; and when the change comes, how dissolvent and destructive it tends to be? Do we not see the same thing in churches and states nearer home—the more that minds are uniformly subjected to one system, the more difficult becomes the adaptation of the old to the new, the more violent, revolutionary and catastrophic the change when it takes place? Safety only lies in the constant differences which many living minds, looking from their own standpoint, in turn contribute. All unity that exists by means of social or artificial restraint of differences, is slowly but inevitably moving toward its own destruction—a destruction that must finally involve much pain and confusion and disorder, because change and adaptation have been so long resisted.

Now if we accept this simple but most far-reaching truth—progress is difference—as I think we must do, let us frankly and loyally accept it with all the great consequences which follow from it. If progress is the child of difference, then it is for us to let our social and political systems favor difference to the fullest extent possible. At no point must we imprison minds under those fighting systems, which always restrain thought and favor mechanical discipline—fighting is one thing and thinking is another; at no point must we stereotype action, preventing its natural and healthy divergence; at no point throw difficulties in the way of effort and experiment; at no point deindividualize men by making them dull repetitions of each other, soulless, automatic ciphers, lost, helpless in their crowd; but everywhere we must allow the natural rewards and inducements and motives to act upon free self-guiding men and women, encouraging them to feel that the work of improvement, the work of world-bettering, the achieving of progress, lies in their own hands, as individuals, and that, if they wish to share in this great common work, they must strive individually to live at their best.

Throughout the whole nation, we must let every man and woman, instead of looking to their parties and parliaments and governments; feel the full strength of the inspiring inducement to do something in their own individual capacities and to join with others in doing something—the smallest or the greatest thing—better than it has yet been done, and so make their own contribution to the great fund of general good.

Only so can the far-reaching powers which lie in human nature, but which, like the talent, are so often wrapped in the napkin, hidden and unused, find their full scope and development; only so can our aims and ambitions be ennobled and purified; only so can the true respect for the individuality of others soften the strife of opinions, and the intolerant spirit in which we so often look upon all that is opposed to and different from ourselves. As we recognize and respect the individuality both of ourselves and others; as we realize that the bettering of the world depends upon our individual actions and perceptions; that this bettering can only be done by ourselves, acting together in free combination; that it depends upon the efforts of countless individuals, as the raindrops make the streams, and the streams make the rivers, that it cannot be done for us by proxy, cannot be relegated, in our present indolent fashion, to systems of machinery, or handed over to an army of autocratic officials to do for us; and as we realize that we shall have failed in our part, have lived almost in vain, if in some direction, in some department of thought or action, whatever it may be, we have not individually striven to make the better take the place of the good; life will become for all of us a better and nobler thing, with more definite aims, and greater incentives to useful action. The work that we do will react on ourselves; and we shall react on the work. Each victory gained, each new thing well done will make the men, the fighters for progress; and as the fighters are raised to a higher capacity, the progress made will advance with bolder, swifter strides, invading in turn every highway and byway of life. But this healthy reaction cannot be as long as we live under the depressing and dispiriting influence of the great machines, that take the work out of our hands, and encourage in us all a sense of personal uselessness. The appeal must be straight and direct to the individuals, to their own self-direction, their own self-sacrifice, to their own efforts in free unregulated combinations, their own willing gifts and services.

It is in vain that you will ask for the progress, that is born in the conflict of competing thoughts and perceptions, from the great official departments, into whose hands you now so complacently resign yourself. They are incapacitated as instruments of progress by the law of their own being. Whenever you act and think wholesale, and in authoritative fashion for others, you become to a certain extent limited and incapacitated in your own nature. That mental penalty forever dogs the possession of power. You lose sight of the great and vital ends, and allow the small things to change places with the all-important things. You are no more in touch with the living forces that make for progress. Why? Are the reasons far to seek? The body of officials—however good and honorable in themselves—from a caste, that administers the administered, and does not really share in the actual life of the nation; the chiefs, intent upon the huge machine, which they direct from behind their office windows; the large body, dutifully following their traditions, and clinging to their precedents. They are cut off from all the great inspirations, for the great inspirations are only likely to come to those who share in the active throbbing life that is not found in any one part, but in the whole, of a free nation, and that exists, as we have seen, as the sum of countless differing contributions.

The best inspirations only readily come to those who live open to all influences, who are not narrowed and limited by that sense of slightly contemptuous superiority, which we all, however excellent we may be, are apt to feel when we are treating others as passive material under our hands. I doubt if you can ever impose your own will by means of force on others, without acquiring in yourself something of this superior scorn. But this scorn is fatal to the great inspirations, for they are only born in us when we are in truest personal sympathy with the upward movement, whatever it may be, when we ourselves are part of it, when we are thinking and feeling freely, and are surrounded by those thinking and feeling like ourselves, for in real free life we are forever giving and receiving, absorbing and radiating. There and there only do you get the true soilbed of progress.

Nor, if our official classes were willing to be helped by the thought of others, is it possible. Under their authoritative systems they have made the people helpless, apathetic, indifferent; and so have to carry the great burden of thinking for a nation on their own shoulders alone. Few people really think or perceive, who can give no practical effect to their thoughts and perceptions; and so it is that we see administered nations grow first indifferent, and then revolutionary. It is thus, in this vicious circle, that bureaucracy ever works. Our bureaucrats, with their universal systems, paralyze and benumb the best thought and energies of the nation; and then themselves are mentally starved in the dead-alive condition of things that they have created. Then again our official classes are not only, like the autocrat, controlled and disabled by their own machinery, but they fall—who could help it?—under the drowsy influence of the ever-revolving wheels. The habit of doing the one thing in the same fixed way depresses the brighter faculties, and the vis inertiae becomes the paramount force. The machinery, on which everything depends, takes the first place; its moral and spiritual effect upon the people take the second or third place, or no place at all. Thus it is that every huge administrative system tends to that barren uniformity which is a kind of intellectual death, and from which that essential element of progress—experiment—is necessarily absent. When you have constructed a universal system, embracing the whole nation, you can't experiment. The thousands of wheels must all follow each other in the same track with undeviating uniformity. Even if your official feelings would allow of such an unorthodox proceeding, it is mechanically very difficult to interfere with the regularity and precision that make the working of universal systems possible.

And so it happens that not only is a man with new ideas a real terror inside the walls of a great department, but that there are two phases that succeed each other in turn in the life of these departments. There is the period of somnolence, the mechanical repetition of what had been said and done in past years, the same sending out of the old time-honored forms, the same pigeonholing of the answers, the same holding of inspections, the same administering of the nation by the junior clerks; and with it all, complete insensibility as to what influence the system as a whole is exercising on the soul of the people. The daily thought and care of a good official begins and ends with taking precautions that the system, as a system, is working smoothly and without friction. As to what the system is in itself, it is not his province to think, and he very rarely does think. He did not create it; he is not directly responsible for it—as a rule nobody knows who is responsible for it; his work is simply to make the countless wheels duly follow each other with regularity and precision. That somnolent period, however, only lasts for a time; presently comes the revolutionary period of remorselessly pulling down and then building up in haste—a period in which the department suddenly awakes from its sleep, aroused perhaps by some external impulse, perhaps by the truer perceptions, or perhaps by the wayward fancies of some minister, fresh to office, who longs to inaugurate his own little revolution. Then the sleepers become changed into reformers; and suddenly we are authoritatively assured that we have been following altogether wrong methods, that the old system, under which serious evils have been growing up, must be at once transformed into something of a new and very different order. The nation, dully and dimly aware that things are not as they should be, smiles approvingly, and through its press, faintly applauds; and the plant, perhaps of some twenty years' growth, is straightway torn up by the roots—a fate which after a few years will be again shared by the new thing that now takes its place.

It is not the fault of the officials. If you or I were in their place we should be just as somnolent, and just as revolutionary. The fault lies in the great system itself; and few of us could resist the spell that it exercises. The truth is that you can no more administer a whole nation than you can represent it. You cannot deal with human nature wholesale; you cannot throw it higgledy-piggledy into one common lot, and let half a dozen men, no better or worse than ourselves, take charge of it. No universal system is a living thing: they all tend to become mere machines—machines of a rather perverse kind, that have incurable tricks of going their own way. We are apt to think that our machines dutifully serve and obey us; but in large measure we serve and obey them. They too have souls of their own, and command as well as obey. Unfortunately for us, progress and improvement are not amongst the things that great machines are able to supply at demand. Their soul lies in mechanical repetition, not in difference; while progress requires not only faculties in the highest state of vital activity, but I might almost say continual, mental dissatisfaction with what has been already achieved, and continual preparedness to invade new territory and attempt new victories. Progress depends upon a great number of small changes and adaptations and experiments constantly taking place, each carried out by those who have strong beliefs and clear perceptions of their own in the matter; for the only true experimenter is he who finds and follows his own way, and is free to try his experiment from day to day. But this true experimentation is impossible under universal systems. An experiment can only be tried on a small scale by those who are the clearer-sighted amongst us, and are aiming at some particular end, and when those who are affected by it are willing to take the risk. You can't rightly experiment with a whole nation; and the consequence is that the sin and mistakes of every universal system go on silently accumulating, until the time comes for the next periodical tearing up by the roots of what exists comes due, and once more we start afresh.

And now there are still many other points on which I must not touch today. There is that great subject of excessive public expenditure in all countries, which is like a tide which flows and flows and hardly ever ebbs. A few years ago when some of us began to preach voluntary taxation, as the only effectual means of recovering the gradually disappearing independence of the individual, and of placing governments in their true position of agents, and not, as they are today, of autocrats and masters of the nation, and as the plainest and most direct means of making the recognition of the principle of individual liberty supreme in our national life, I found most of my friends quite content to be used as tax material, even though the sums of money taken from them were employed against their own beliefs and interests. They had lived so long under the system of using others, and then in their turn being used by them, that they were like hypnotized subjects, and looked on this subjecting and using of each other as a part of the necessary and even providential order of things. The great machine had taken possession of their souls; and they only yawned and looked bored, or slightly scornful at any idea of rebelling against it.

In vain we drew the picture of the nobler, happier, safer life of the nation, when men of all conditions voluntarily combined to undertake the great services, class cooperating with class, each bound to the other by new ties of friendship and kindliness, with all its different groups learning to discover their own special wants, to follow their own methods, and make their own experiments. In that way only, as we urged, could we replace the present dangerous and mischief-making strife with blessed fruitful peace, create a happier, better, nobler spirit amongst us all, destroy the old traffic and bargaining of the political market, destroy the fatal belief that one class might rightly prey upon another class, and that all property finally belonged to those who could collect the greater number of votes at the polls. That belief in the omnipotent vote, as we urged, was striking its roots deeper every year—it was the certain, the inevitable result of our party fighting for the possession of power. So long as the vote carried with it the unlimited undefined power of the majority, the giving away of property must always remain as the easiest means of purchasing the owners of the vote; and that belief in the final ownership of property being vested in the voter we could only fight, not by resisting here or there, not by denouncing this or that bit of excessive and wasteful expenditure, but by challenging the rightfulness and good sense of the whole system, by pointing to a truer, nobler, social life, and by resolutely standing on the plain broad principle of individual control over ourselves and our own property. It was in friendly voluntary cooperation, as free men and women, for all public wants and services; in taking each other's hands, in sharing our efforts; it was by destroying the belief in power, the belief in “pooling” property and faculties, the belief in the false right of some men to hold other men in subjection, and to use them as their material; in building up the belief in the true rights, the rights of self-ownership and self-guidance, apart from which everything tends to the confusion and corruption of public life—it was only so that we could ward off the coming danger and the inevitable strife. These great national services, that we had so lightly flung into the hands of our officials, were the true means of creating that higher and better national life, with its friendly interdependence, its need of each other, its respect for each other, which was worth over and over again all the political gifts and compulsions—though you piled them up in a heap as high as Pelion thrown on the top of Ossa. It was only so that the nation would find its true peace and happiness, and that the smoldering dread and hatred of each other could die out.

The years have passed; and I think a change of mood has silently come over many persons. I find that some of those who once clung to compulsion as the saving social bond, as the natural expression of nation life, are willing today to consider whether some better and truer and safer principle may not be found; are willing to consider, as a practical question, if some limit should not be placed on the power to take and to spend in unmeasured quantity the money of others. Our friend the socialist has done, and is doing for us his excellent and instructive work. He stands as a very striking, I might say eloquent landmark, showing us plainly enough where our present path leads, and what is the logical completion of our compulsory interferences, our restrictions of faculties, and our transfer of property by the easy—shall I say the laughable and grotesque?—process of the vote. Into our present system, which so many men accept without thinking of its real meaning, and its further consequences, he introduces an order, a consistency, a completeness of his own. His logic is irresistible. If you can vote away half the yearly value of property under the form of a rate, as we do in some towns at present, then under the same convenient and elastic right you can vote away the nine-tenths or the whole. “Only logic,” perhaps you lightly answer—but remember, unless you change the direction of the forces, logic always tends to come out victorious in the end.

Let us then take the bolder, the truer, the more manful course. If we believe in property, as a right and just thing; if, as the product of faculties, we believe it to be inseparably connected with the free use of faculties, and therefore inseparably connected with freedom itself; if we believe that it is a mere bit of word mockery to tell us, as our socialist friends do, that they are presenting the world with the newest, the most perfect, the most up-to-date form of liberty, while from their heights of scorn for liberty they calmly deny to all men and women the right to employ their faculties in their own way and for their own advantages, offering us in return a system beyond all words petty and irritating, a system that would provoke rebellion even in the nursery, and which, as a clever French writer wittily remarked, would periodically convulse the state with the ever-recurring insoluble question, might or might not a wife mend the trousers of her husband; if we believe that the socialist, treading in the footsteps of his predecessor, the autocrat, has only discovered one more impossible system of slavery, then let us individually do our best to end the great delusion that has given birth to the socialist, and made him the power that he is today in Europe—that property belongs, not to the property owner, but to those who are good enough to take the trouble to vote.