Auberon Herbert, “A Plea for Voluntaryism” (1908)

|

The Ruling Class and the State: An Anthology from the OLL Collection[See the Table of Contents of this Anthology as well as the more comprehensive collection The OLL Reader] |

Auberon Herbert, "A Plea for Voluntaryism" (1908)

[Created: January 17, 2018]

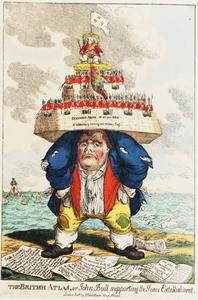

The image is James Gillray, "The British Atlas, or John Bull supporting the Peace Establishment" (1816). [See a higher resolution image and the illustrated essay on "James Gillray on War and Taxes during the War against Napoleon".

Source

Auberon Herbert, The Right and Wrong of Compulsion by the State, and Other Essays, ed. Eric Mack (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1978).

- "Essay Nine. A Plea for Voluntaryism." - This essay was published in The Voluntaryist Creed (Oxford University Press, 1908). It was completed shortly before Herbert's death as a series of lectures for the British Constitution Association and never circulated for supporting signatures, as originally intended. </titles/591#lf0146_head_029>

More about Auberon Herbert (1838-1906),

ESSAY NINE. A PLEA FOR VOLUNTARYISM (1908)

We, who call ourselves voluntaryists, appeal to you to free yourselves from these many systems of state force, which are rendering impossible the true and happy life of the nations of today. This ceaseless effort to compel each other, in turn for each new object that is clamored for by this or that set of politicians, this ceaseless effort to bind chains round the hands of each other, is preventing progress of the real kind, is preventing peace and friendship and brotherhood, and is turning the men of the same nation, who ought to labor happily together for common ends, in their own groups, in their own free unfettered fashion, into enemies, who live conspiring against and dreading, often hating each other.

Look at the picture that you may see today in every country of Europe. Nations divided into two or three parties, which are again divided into several groups, facing each other like hostile armies, each party intent on humbling and conquering its rivals, on treading them under their feet, as a conquering nation crushes and tramples on the nation it has conquered. What good, what happiness, what permanent progress of the true kind can come out of that unnatural, denationalizing, miserable warfare? Why should you desire to compel others; why should you seek to have power— that evil, bitter, mocking thing, which has been from of old, as it is today, the sorrow and curse of the world—over your fellow-men and fellow-women? Why should you desire to take from any man or woman their own will and intelligence, their free choice, their own self-guidance, their inalienable rights over themselves; why should you desire to make of them mere tools and instruments for your own advantage and interest; why should you desire to compel them to serve and follow your opinions instead of their own; why should you deny in them the soul—that suffers so deeply from all constraint—and treat them as a sheet of blank paper upon which you may write your own will and desires, of whatever kind they may happen to be? Who gave you the right, from where do you pretend to have received it, to degrade other men and women from their own true rank as human beings, taking from them their will, their conscience, and intelligence—in a word, all the best and highest part of their nature—turning them into mere empty worthless shells, mere shadows of the true man and women, mere counters in the game you are mad enough to play, and just because you are more numerous or stronger than they, to treat them as if they belonged not to themselves, but to you? Can you believe that good will ever come by morally and spiritually degrading your fellow-men? What happy and safe and permanent form of society can you hope to build on this pitiful plan of subjecting others, or being yourselves subjected by them?

We show you the better way. We ask you to renounce this old, weary, hopeless way of force, ever tearstained and bloodstained, which has gone on so long under emperors and autocrats and governing classes, and still goes on today amongst those who, while they condemn emperors and autocrats, continue to walk in their footsteps, and understand and love liberty very little more than those old rulers of an old world. We bid you ask yourselves—What is all our boasted civilization and gain in knowledge worth to us, if we are still, like those who had not attained to our civilization and knowledge, to hunger for power, still to cling to the ways of strife and bitterness and hatred, still to oppress each other as in the days of the old rulers? Don't be deceived by mere words and phrases. Don't think that everything was gained when you got rid of autocrat and emperor. Don't think that a change in the mere form—without change in the spirit of men—can really alter anything, or make a new world. A voting majority, that still believes in force, that still believes in crushing and ruling a minority, can be just as tyrannous, as selfish and blind, as any of the old rulers. Happy the nation that escapes from autocrat, from emperor, and from its bureaucratic tyrants; but that is only the beginning of the new good life; that counts only for the first steps in the true path. When that is done, the true goal has still to be won, the great lesson still remains to be learned. The old curse, the old sorrow, did not simply lie in the heart of autocrat and emperor; it lay in the common desire of men to rule and possess for their own advantage the minds and bodies of each other. It is that fatal, deluding desire which even yet today prevents our realizing the true and happy life. As a writer has well said—many nations have been powerful, but has any one of them found the true life—as yet? It is this vainest of all vain desires that we have to renounce, trample upon, cast clean out of our hearts, if we are to win the better things. We have to learn that our systems of force destroy all the great human hopes and possibilities; that as long as we believe in force there can be no abiding peace or friendship between us all; that a half-disguised civil war will forever smolder in our midst; that each half of the nation must live, as it were, sword in hand, ever watching the other half, and given up, as we said, to suspicion and dread and hatred, knowing that, if once defeated in the great contest, its own deepest belief and interests will be roughly set aside and trampled on; that it must accept the hard lot of the conquered, kneeling down in the dust and submitting to whatever its opponents choose to decree for it; that it will have no rights of its own; no rights over its own life, over its own actions and property; no share in the common country, no share in the guidance of its fortunes; no voice in the laws passed; it will be a mere helpless crowd, defranchised, and decitizenized, a degraded and subject race, bound to do the hard bidding of its conquerors. Can you for a single moment believe that the subjecting of others in this conqueror's and conquered fashion is the true end of our existence here, the true fulfilling of man's nature, with all its great gifts and hopes and aspirations?

And are the conquerors in the great conflict better off —if we try to see clearly—than the conquered? We can only answer no; for power is one of the worst, the most fatal and demoralizing of all gifts you can place in the hands of men. He who has power—power only limited by his own desires—misunderstands both himself and the world in which he lives; he sees through a glass darkly, which dims and perverts his whole vision; he magnifies and exalts his own little self; he fondly imagines he may follow the lusts of his heart wherever they lead him; and disowns the control of the great principles, that stand forever above us all, and refuses, alike to the autocrat and the voting majority, the rule and the subjecting of the lives of others. If we feel shame and sorrow for those who are subjected, we may feel yet more shame and sorrow for the blind, self-deceiving instruments of their subjection. They in their pride sink to a lower depth than those whom they subject. Better it were to be amongst those who wear the chain than amongst those who bind it on the hands of other men. For those who suffer in subjection there is some hope, some glimmering of light, some teachings that come from the passionate desire for the liberty denied to them; but for those who cling to and believe in possessing power there is only darkness of soul, where no light enters, until at last, through a long bitter experience, they learn how that for which they sacrificed so much has only turned to their own deepest injury. See how power hardens and brutalizes all of us. It not only makes us selfish, unscrupulous, and intriguing, scornful and intolerant, corrupt in our motives, but it veils our eyes and takes from us the gift of seeing and understanding. Power and stupidity are forever wedded together. Cunning there may be; but it is a cunning that in the end tricks and deceives itself. Power forever tends not only to develop in us the knave, but also to develop the fool. If you wish to know how power spoils character and narrows intelligence, look at the great military empires; their steady perseverance in the roads that lead to ruin; their dread of free thought and of liberty in all its forms; look at the sharp repressions, the excessive punishments, the love of secrecy, the attempt to drill a whole nation into obedience, and to use the drilled and subject thing for every passing vanity and aggrandizement of those who govern. Look also at the great administrative systems. See how men become under them helpless and dispirited, incapable of free effort and self-protection, at one moment sunk in apathy, at another moment ready for revolution. Do you wonder that it is so? Is it wonderful that when you replace the will and intelligence and self-guidance of the individual by systems of vast machinery, that men should gradually lose all the better and higher parts of their nature—for of what use to them is that better and higher part, when they may not exercise it? Ought we to feel surprise, when we see them become like overrestrained children, peevish, discontented and quarrelsome, unable to control and direct themselves, and ever loud in their complaints that enough cake and jam do not fall to their share?

Endless are the evils that power brings with it, both to those who rule and are ruled. If you hold power, your first aim and end are necessarily to preserve that power. With power, as you fondly imagine, you possess all that the world has to offer; without power you seem to your- self only portionless, abject, humiliated—the gate flung in your face, that leads to the palace of all the desirable things. When you once play for so vast a stake, what influence can mere right or wrong have in your counsels? The course that lies before you may be right or wrong, tolerant or intolerant, wise or foolish, but the fatal gift of power, that you have been mad enough to desire and to grasp at, gives you no choice. If you mean to have and to hold power, you must do whatever is necessary for the having and holding of it. You may have doubts and hesitations and scruples, but power is the hardest of all taskmasters, and you must either lay these aside, when you once stand on that dangerous, dizzy height, or yield your place to others, and renounce your part in the great conflict. And when power is won, don't suppose that you are a free man, able to choose your path and do as you like. From the moment you possess power, you are but its slave, fast bound by its many tyrant necessities. The slave owner has no freedom; he can never be anything but a slave himself, and share in the slavery that he makes for others. It is, I think, plain it must be so. Power once gained, you must anxiously day by day watch over its security, whatever its security costs, to prevent the slippery thing escaping from your hands. You tremble at every shadow that threatens its existence. You are haunted by a thousand dreads and suspicions. It becomes, whether you wish it or not, your first, your highest law, and all other things fall into the second and third place. Once you plunge into virtually a burthen imposed, you must go where the strong tide carries you; you must put away conscience and sense of right, and play the whole game relentlessly out, with the unflinching determination to win what you are striving for. In that great game there is no room left for inconvenient and embarrassing scruples. You can't afford to let your opponents defeat you and wrest the power that you hold from your hands. You can't afford to let them become your masters and trample, as conquerors, upon all the rights and beliefs that are sacred to you. Whatever the price to pay, whatever sacrifice it demands of what is just and upright and honorable, you must harden your heart, and go on to the bitter end. And thus it is that seeking for power not only means strife and hatred, the splitting of a nation into hostile factions, but forever breeds trick and intrigue and falsehood, results in the wholesale buying of men, the offering of this or that unworthy bribe, the playing with passions, the poor unworthy trade of the bitter unscrupulous tongue, that heaps every kind of abuse, deserved or not deserved, upon those who are opposed to you, that exaggerates their every fault, mistake, and weakness, that caricatures, perverts their words and actions, and claims in childish and absurd fashion that what is good is only to be found in your half of the nation, and what is evil is only to be found in the other half.

Such are the fruits of the strife for power. Evil they must be, because power is evil in itself. How can the taking away from a man his intelligence, his will, his self-guidance be anything but evil? If it were not evil in itself, there would be no meaning in the higher part of nature, there would be no guidance in the great principles—for power, if we once acknowledge it, must stand above everything else, and cannot admit of any rivals. If the power of some and the subjection of others are right, then men would exist merely as the dust to be trodden under the feet of each other; the autocrats, the emperors, the military empires, the socialist, perhaps even the anarchist with his detestable bomb, would each and all be in their own right, and find their own justification; and we should live in a world of perpetual warfare, that some devil, as we might reasonably believe, must have planned for us. To those of us who believe in the soul—and on that great matter we who sign hold different opinions—the freedom of the individual is not simply a question of politics, but it is a religious question of the deepest meaning. The soul to us is by its own nature a free thing, living its life here in order that it may learn to distinguish and choose between the good and the evil, to find its own way—whatever stages of existence may have to be passed through—toward the perfecting of itself. You may not then, either for the sake of advancing your own interests, or for the sake of helping any cause, however great and desirable in itself, in which you believe, place bonds on the souls of other men and women, and take from them any part of their freedom. You may not take away the free life, putting in its place the bound life. Religion that is not based on freedom, that allows any form of servitude of men to men, is to us only an empty and mocking word, for religion means following our own personal sense of right and fulfilling the commands of duty, as we each can most truly read it, not with the hands tied and the eyes blinded, but with the free, unconstrained heart that chooses for itself. And see clearly that you cannot divide men up into separate parts—into social, political and religious beings. It is all one. All parts of our nature are joined in one great unity; and you cannot therefore make men politically subject without injuring their souls. Those who strive to increase the power of men over men, and who thus create the habit of mechanical obedience, turning men into mere state creatures, over whose heads laws of all kinds are passed, are striking at the very roots of religion, which becomes but a lifeless, meaningless thing, sinking gradually into a matter of forms and ceremonies, whenever the soul loses its freedom. Many men recognize this truth, if not in words, yet in their hearts, for all religions of the higher kind tend to become intensely personal, resting upon that free spiritual relation with the great Oversoul—a relation that each must interpret for himself. And remember you can't have two opposed powers of equal authority; you can't serve two masters. Either the religious conscience and sense of right must stand in the first place, and the commands of all governing authorities in the second place; or the state machine must stand first, and the religious and moral conscience of men must follow after in humble subjection, and do what the state orders. If you make the state supreme, why should it pay heed to the rule of conscience, or the individual sense of right; why should the master listen to the servant? If it is supreme, let it plainly say so, take its own way, and pay no heed, as so many rulers before them have refused to do, to the conscience of those they rule.

And here we ought to say that amongst those who sign this appeal are some who, like the late Mr. Bradlaugh— a devoted fighter for liberty—reject the doctrine of soul and would not, therefore, base their resistance to state power on any religious ground. But apart from this great difference that may exist between us, we, who sign, are united by the same detestation of state power, and by the same perception of the evils that flow from it. We both see alike that placing unlimited power—as we do now—in the hands of the state means degrading men from their true rank, the narrowing of their intelligence, the encouragement of intolerance and contempt for each other, and therefore the encouragement of sullen, bitter strife, the tricks of the clever tongue, practiced on both the poor and rich crowd, and the evil arts of flattery and self-abasement in order to conciliate votes and possess power, the excessive and dangerous power of a very able press, which keeps parties together, and too often thinks for most of us, the repression of all those healthy individual differences that make the life and vigor of a nation, the blind following of blind leaders, the reckless rushing into national follies, like the unnecessary Boer War—that might have been avoided, as many of us believe, with a moderate amount of prudence, patience, and good temper—just because the individuals of the nation have lost the habit of thinking and acting for themselves, have lost control over their own actions, and are bound together by party ties into two great childlike crowds; means also the piling up of intolerable burdens of debt and taxation, the constant and rather mean endeavor to place the heaviest of these burdens on others—whoever the others may be, the carelessness, the high-handedness, the insolence of those who spend money compulsorily taken, the flocking together of the evil vultures of many kinds where the feast is spread, the deep poisonous corruption, such as is written in broad characters over the government of some of the large towns in the United States—a country bound to us by so many ties of friendship and affection, and in which there is so much to admire—a corruption, that in a lesser degree has soiled the reputation of some of the large cities of the Continent, and is already to be found here and there sporadically existing amongst us in our own country; and which only too surely means at the end of it all the setting up of some absolute form of government, to which men fly in their despair, as a refuge from the intolerable evils they have brought upon themselves—a refuge that after a short while is found to be wholly useless and impotent, and is then violently broken up, perhaps amidst storm and bloodshed, to be once more succeeded by the long train of returning evils, from which men had sought to escape in the vain hope that more power would heal the evils that power had brought upon them.

Such are the fruits of power and the strife for power. It must be so. Set men up to rule their fellow-men, to treat them as mere soulless material with which they may deal as they please, and the consequence is that you sweep away every moral landmark and turn this world into a place of selfish striving, hopeless confusion, trickery and violence, a mere scrambling ground for the strongest or the most cunning or the most numerous. Once more we repeat—don't be deluded by the careless everyday talk about majorities. The vote of a majority is a far lesser evil than the edict of an autocrat, for you can appeal to a majority to repent of its sins and to undo its mistakes, but numbers—though they were as the grains of sand on the seashore—cannot take away the rights of a single individual, cannot turn man or woman into stuff for the politician to play with, or overrule the great principles which mark out our relations to each other. These principles are rooted in the very nature of our being, and have nothing to do with minorities and majorities. Arithmetic is a very excellent thing in its place, but it can neither give nor take away rights. Because you can collect three men on one side, and only two on the other side, that can offer no reason—no shadow of a reason—why the three men should dispose of the lives and property of the two men, should settle for them what they are to do, and what they are to be: that mere rule of numbers can never justify the turning of the two men into slaves, and the three men into slave owners. There is one and only one principle, on which you can build a true, rightful, enduring and progressive civilization, which can give peace and friendliness and contentment to all differing groups and sects into which we are divided—and that principle is that every man and woman should be held by us all sacredly and religiously to be the one true owner of his or her faculties, of his or her body and mind, and of all property, inherited or—honestly acquired. There is no other possible foundation—see it wherever you will—on which you can build, if you honestly mean to make this world a place of peace and friendship, where progress of every kind, like a full river fed by its many streams, may flow on its happy fertilizing course, with ever broadening and deepening volume. Deny that principle, and we be- come at once like travelers who leave the one sure and beaten path and wander hopelessly in a trackless desert. Deny that self-ownership, that self-guidance of the individual, and however fine our professed motives may be, we must sooner or later, in a world without rights, become like animals, that prey on each other. Deny human rights, and however little you may wish to do so, you will find yourself abjectly kneeling at the feet of that Old World god Force—that grimmest and ugliest of gods that men have ever carved for themselves out of the lusts of their hearts; you will find yourselves hating and dreading all other men who differ from you; you will find yourselves obliged by the law of the conflict into which you have plunged, to use every means in your power to crush them before they are able to crush you; you will find yourselves day by day growing more unscrupulous and intolerant, more and more compelled by the fear of those opposed to you, to commit harsh and violent actions, of which you would once have said, Is thy servant a dog that she should do these things? You will find yourselves clinging to and welcoming Force, as the one and only form of protection left to you, when you have once destroyed the rule of the great principles. When once you have plunged into the strife for power, it is the fear of those who are seeking for power over you that so easily persuades to all the great crimes. Who shall count up the evil brood that is born from power—the pitiful fear, the madness, the despair, the overpowering craving for revenge, the treachery, the unmeasured cruelty? It is liberty alone, broad as the sky above our heads, and planted deep and strong as the great mountains, that allows the better and higher part of our nature to rule in us, and subdues those passions that we share with the animals.

We ask you then to limit and restrain power, as you would restrain a wild and dangerous beast. Make everything subservient to liberty; use state force only for one purpose—to prevent and restrain the use of force amongst ourselves, and that which may be described as the twin brother of force, wearing a mask over its features, the fraud, which by cunning sets aside the consent of the individual, as force sets it aside openly and violently. Restrain by simple and efficient machinery the force and fraud that some men are always ready to employ against other men, for whether it is the state that employs force against a part of the citizens, or one citizen who employs force or fraud against another citizen, in both cases it is equally an aggression upon the rights, upon the self-ownership of the individual; it is equally in both cases the act of the stronger who in virtue of his strength preys upon the weaker. Safeguard therefore the lives and the property of every citizen against the force or the cunning of Bill Sykes and all his tribe. Make of our world a fair open field where we may all act, according to our own choice, individually, or in cooperation, for every unaggressive purpose, and where good of every kind will fight its own open unrestrained fight with evil of every kind. Don't believe in suppressing by force any form of evil—always excepting the direct attacks upon person and property. An evil suppressed by force is only driven out of sight under the surface—there to fester in safety and to take new and more dangerous forms. Remember that striking story of the German liberals, when Bismarck had directed his foolish and useless weapon of repressive laws against the socialists. “You have driven the socialists into silence”—they said—“you have forbidden their meetings and confiscated their papers; yet for all that the movement goes on more actively than ever underground and hidden from sight. And we who are opposed to socialism are also silenced. We have now no enemy to attack. The enemy has vanished out of our sight and out of our reach. How can we answer or reason with those who speak and write no word in public, and only teach and make new recruits in secret and in the dark?”

So it is always. You strike blindly, like a child in its passion, with your weapons of force, at some vice, at some social habit, at some teaching you consider dangerous, and you disarm your own friends who would fight your battle for you—were they allowed to do so—in the one true way of discussion and persuasion and example. You prevent discussion, and the expression of all healthier opinion, you disarm the reformers and paralyze their energies—the reformers who, if left to themselves, would strive to move the minds of men, and to win their hearts, but who now resign themselves to sleep and to indifference, fondly believing that you with your force have fought and won their battle for them, and that nothing now remains for them to do. But in truth you have done nothing; you have helped the enemy. You may have made the outside of things more respectable to the careless eye, you may have taught men to believe in the things that seem, and in reality are not; but you have left the poisonous sore underneath to work its own evil undisturbed, in its own way and measure. The evil, whatever it was, was the result of perverted intelligence or perverted nature; and your systems of force have left that intelligence and that nature unchanged; and you have done that most dangerous of all things—you have strengthened the general belief in the rightfulness and usefulness of employing force. Do you not see that of all weapons that men can take into their hands force is the vainest, the weakest? In the long dark history of the world, what real, what permanent good has ever come from the force which men have never hesitated to use against each other? By force the great empires have been built up, only in due time to be broken into pieces, and to leave mere ruins of stones to tell their story. By force the rulers have compelled nations to accept a religion—only in the end to provoke that revolt of men's minds which always in its own time sweeps away the work of the sword, of the hangman and the torture table. What persecution has in the end altered the course of human belief? What army, used for ambitious and aggressive purposes, has not at last become as a broken tool? What claim of a church to exercise authority and to own the souls of men has not destroyed its own influence and brought certain decay on itself? Is it not the same today, as it has been in all the centuries of the past? Has not the real prosperity, the happiness, the peace of a nation increased just in proportion as it has broken all the bonds and disabilities that impeded its life, just in proportion as it has let liberty replace force; just in proportion as it has chosen and established for itself all rights of opinion, of meeting, of discussion, rights of free trade, rights of the free use of faculties, rights of self-ownership as against the wrongs of subjection? And do you think that these new bonds and restrictions in which the nations of today have allowed themselves to be entangled—the conscription which sends men out to fight, consenting or not consenting, which treats them as any other war material, as the guns and the rifles dispatched in batches to do their work; or the great systems of taxation, which make of the individual mere tax material, as conscription makes of him mere war material; or the great systems of compulsory education, under which the state on its own unavowed interest tries to exert more and more of its own influence and authority over the minds of the children, tries—as we see especially in other countries—to mold and to shape those young minds for its own ends—“Something of religion will be useful—school-made patriotism will be useful—drilling will be useful”—so preparing from the start docile and obedient state material, ready-made for taxation, ready-made for conscription—ready-made for the ambitious aims and ends of the rulers—do you think that any of these modern systems, though they are more veiled, more subtle, less frank and brutal than the systems of the older governments, though the poison in them is more thickly smeared with the coating of sugar, will bear different fruit, will work less evil amongst us all, will endure longer than those other broken and discredited attempts, which men again and again in their madness and presumption have made to possess themselves of and to rule the bodies and minds of others? No! one and all they belong to the same evil family; they are all part of the same conspiracy against the true greatness of human nature; they are all marked broad across the forehead with the same old curse; and they will all end in the same shameful and sorrowful ending. Over us all is the great unchanging law, ever the same, unchanged and unchanging, regardless of all our follies and delusions, that come and go, that we are not to take possession of and rule the body and mind of others; that we are not to take away from our fellow beings their own intelligence, their own choice, their own conscience and free will; that we are not to allow any ruler, be it autocrat, emperor, parliament, or virtually a burthen imposed, to take from any human being his own true rank, making of him the degraded state material that others use for their own purposes.

“But”—some of your friends may say—“look well at the advantages of this state force. See how many good things come to you by taking money out of the pockets of others. Would the rich man continue to serve your needs, if you had not got your hands upon him, and held him powerless under your taxation system? No! He would be only too glad to find an escape from it. Keep then your close grips upon him, now that you once hold him in it; and by more and more skillful and searching measures relieve him of what you want so much, and what is merely superfluous to him. Why spare your beast of burden? What is the use of your numbers, of your organizations, of the all-powerful vote, that can alone equalize conditions, making the poor man rich, and the rich man poor, if you are tempted to lay the useful weapon of force aside? Force in the old days was used against you; it is your turn now to use force, and spare not. Think well of what the vote can do for you. There lies the true magician's wand. You want pensions, provision for old age and sickness, land, houses, a minimum wage, lots and lots of education, breakfast and dinner for the children who go to school, scholarships for the clever pupils, libraries, museums, public halls, national operas, amusements and recreations of all kinds, and many another good thing which you will easily enough discover when you once begin to help yourselves—for, as the French say, the appetite comes with the eating; and there stand the richer classes with their laden pockets, only encumbered with the wealth that, if they knew it, they would be better without, defenseless, comparatively few and weak, with no power to stand against the resistless vote, if you once turn your strength to good account and learn how to organize your numbers for the great victory. Of course they will give you excellent reasons why you should keep your hands off them, and let them go free. Don't be fooled any longer by mere words. Force rules everything in this world; and today it is at last your turn to use force, and enter into possession of all that the world has to offer.”

We answer—that all such language is the language of passionate unthinking children, who, regardless of right or wrong, with no questions of conscience, no perception of consequences, snatch at the first glittering thing that they see before them; that those who once listen to these counsels of violence would be changed in their nature from the reasonable man to the unreasonable beast; that all such counsels mean revolt against the great principles, against the honest and true methods that alone can redeem this world of ours, that, if faithfully followed, will in the end make a society happy, prosperous and progressive in its every part, ever leveling up, ever peacefully redistributing wealth, ever turning the waste places of life into the fruitful garden. But in violence and force there is no redemption. Force—whether disguised or not under the forms of voting—has but one meaning. It means universal confusion and strife; it means flinging the sword—that has never yet helped any of us—into the scale and preparing the way for the utterly wasted and useless shedding of much blood. Even if these good things, and many more of the same kind, lay within your grasp, waiting for your hand to close upon them, you have no right to take them by force, no right to make war upon any part of your fellow citizens, and to treat them as mere material to serve your interests. The rich man may no more be the beast of burden of the poor man, than the poor may be the beast of burden of the rich. Force rests on no moral foundations; you cannot justify it; it rests on no moral basis; you cannot reconcile it with reason and conscience and the higher nature of men. It lies apart in its own evil sphere, separated by the deepest gulf from all that makes for the real good of life—a mere devil's instrument. Even if force tomorrow could lay at your feet all the material gifts which you rightly desire, you may not, you dare not, for the sake of the greater good, for the sake of the higher nature that is in all of us, for the sake of the great purposes and the nobler meanings of life, accept what it offers. Our work is to make this life of ours prosperous, happy and beautiful for all who share in it, working with the instruments of liberty, of peace, and of friendship—these and these only are the instruments which we may take in our hands, these are the only instruments that can do our work for us.

Those who bid you use force are merely using language of the same kind as every bloodstained ruler has used in the past, the language of those who paid their troops by pillage, the language of the war-loving German general, who in old days looked down from the heights surrounding Paris, and whispered with a gentle sigh—“What a city to sack!” It is the language of those who through all the past history of the world have believed in the right of conquering, in the right of making slaves, who have set up force as their god, who have tried to do so by the violent hand whatever smiled to their own desires, and who only brought curses upon themselves, and a deluge of blood and tears upon the world. Force—whatever forms it takes—can do nothing for you. It can redeem nothing; it can give you nothing that is worth the having, nothing that will endure; it cannot even give you material prosperity. There is no salvation for you or for any living man to be won by the force that narrows rights, and always leaves men lower and more brutal in character than it found them. It is, and ever has been the evil genius of our race. It calls out the reckless, violent, cruel part of our nature, it wastes precious human effort in setting men to strive one against the other; it turns us into mere fighting animals; and ends, when men at last become sick of the useless strife and universal confusion, in “the man on the black horse” who calls himself and is greeted as “the savior of society.” Make the truer, the nobler choice. Resist the blind and sordid appeal to your interests of the moment, and take your place once and for good on the side of the true liberty, that calls out all the better and higher part of our nature, and knows no difference between rulers and ruled, majorities and minorities, rich and poor. Declare once and for good that all men and women are the only true owners of their faculties, of their mind and body, of the property that belongs to them; that you will only build the new society on the one true foundation of self-ownership, self-rule, and self-guidance; that you turn away from and renounce utterly all this mischievous, foolish and corrupt business of compelling each other, of placing burdens upon each other, of making force, and the hateful trickery that always goes with it, into our guiding principles, of treating first one set of men and then another set of men as beasts of burden, whose lot in life it is to serve the purposes of others. True it is that there are many and many things good in themselves which you do not yet possess, and which you rightly desire, things which the believers in force are generous enough to offer you in any profusion at the expense of others; but they are merely cheating you with vain hopes, dangling before your eyes the mocking shows of things that can never be. Force never yet made a nation prosperous. It has destroyed nation after nation, but never yet built up an enduring prosperity. It is through your own free efforts, not through the gifts of those who have no right to give them, that all these good things can come to you; for great is the essential difference between the gift—whether rightly or wrongly given—and the thing won by free effort. That which you have won has made you stronger in your-selves, has taught you to know your own power and resources, has prepared you to win more and more victories. The gift flung to you has left you dependent upon others, distrustful and dispirited in yourselves. Why turn to your governments as if you were helpless in yourselves? What power lies in a government, that does not lie also in you? They are only men like you—men, in many ways disadvantaged, overweighted by the excessive burdens they have taken on themselves, seldom able to give concentrated attention to any one subject, however important; necessarily much under the influence of subordinates, from whom they must gather the information on which they have to act; often turned from their own course by the dissensions and differences of their followers; always obliged to plan and maneuver in order to keep their party together, and then losing their own guiding purpose, and tempted into misleading and unworthy courses; often deciding the weightiest matters in a hurry, as in the case of the famous Ten Minutes Reform Bill; and physically leading a life which overtaxes health and endurance with the call made upon it, by the care of their own office, their attendance far into the night at the House, their social occupations, the necessity to follow carefully all that is passing in the great theater of European politics, and of studying the questions which each week brings with it. Think carefully, and you will feel that all these rash attempts of the handful of men, that we call a government, to nurse a nation are a mere delusion. You can't throw the cares and the wants and the hopes of a whole people on some sixteen or eighteen overburdened workers. You might as well try to put the sea into a quart pot. A handful of men can't either think or act for you. Their task is impossible. If they try to do so, they can only be as blind guides who lead blind followers into the ditch. It all ends in scramble and confusion, in something being done in order to have something to show, in great expectations and woeful disappointments, in rash action and grievous mistakes, resulting from hurry and overpressure and insufficient knowledge, which lead the nation in wrong directions, and bring their long train of evil consequences. Why place your fortunes, all that you have, and all that you are, in other hands? You have in yourselves the great qualities—though still undeveloped—for supplying in your own free groups the growing wants of your lives. You are the children of the men who did so much for themselves, the men who broke the absolute power; who planted the colonies of our race in distant lands, who created our manufacturers, and carried our trade to every part of the world; who established your cooperative and benefit societies, your trade unions, who built and supported your Nonconformist churches. In you is the same stuff, the same power to do, as there was in them; and if only you let their spirit breathe again in you, and tread in their footsteps, you may add to their triumphs and successes tenfold and a hundredfold. As the French well say: “Ou les pères ont passé, passeront bientôt les enfants” (Where the fathers passed, there soon shall the children pass). To this point—the work to be undertaken in your own free groups, without any compulsion and subjection of others—we will return later.

But nothing can be well and rightly done, nothing can bear the true fruit, until you become deeply and devotedly in love with personal liberty, consecrating in your hearts the great and sacred principle of self-ownership and self-direction. That great principle must be our guiding star through the whole of this life's pilgrimage. Away from its guiding we shall only continue to wander, as of old, hopelessly in the wilderness. For its sake we must be ready to make any and every sacrifice. It is worth them all—many times worth them all. For its sake you must steadily refuse all the glittering gifts and bribes which many politicians of both parties eagerly press upon you, if you will but accept them as your leaders, and lend them the power which your numbers can give. Enter into none of these corrupt and fatal compacts. All such leaders are but playing with you, fooling you for their own ends. In the pride and vanity of their hearts they wish to bind you to them, to make you dependent upon them. You are to fight their battles, and you will be paid in return much in the same manner as the old leaders paid their soldiers by giving them a conquered city to sack. Can any real good come to you by following that unworthy and mercenary path? When once you have become a mere pillaging horde, when once you have lost all guidance and control and purpose of your own, bound to your leaders, and dependent on them for the sake of the spoils that they fling to you, do you think that any of the greater and nobler things of life will still be possible to you? The great things are only possible for those who keep their hearts pure and exalted, and their hands clean, who are true to themselves, who follow and serve the fixed principles that are above us all, and are our only true guides, who never sell themselves into the hands of others. Your very leaders, who have cheated you, and used you, will despise you; and in your own hearts, if you dare honestly to search into them, you will despise yourselves. But your self-contempt will hardly help you. You will have lost the great qualities of your nature; the old corrupt contract, into which you have entered, will still bind you; you may in your wild discontent revolt against your leaders; but as in the legends of the evil controlling spirit, that both serves and enslaves, you will each be a fatal necessity to the other. You have linked your fortunes together, and it will be hard to dissolve the partnership. Remember ever the old words—as true today as when they were first spoken—“What shall it profit a man if he gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?” If you lose all respect for the rights of others, and with it your own self-respect; if you lose your own sense of right and fairness, if you lose your belief in liberty, and with it the sense of your own worth and true rank; if you lose your own will and self-guidance and control over your own lives and actions, what can all the buying and trafficking, what can all the gifts of politicians give you in return? Why let the true diamond be taken from you in exchange for the worthless bit of glass? Is not the ruling of your own selves worth a hundred times this mad attempt to rule over others? If your house were filled with silver and gold, would you be happy if your own self no more belonged to you? Have you ever carefully thought out what life would be like under the schemes of the socialist party, who offer us the final, the logical completion of all systems of force? Try to picture the huge overweighted groaning machine of government; the men who direct it vainly, miserably struggling with their impossible task of managing everything, driven for the sake of their universal system to extinguish all differences of thought and action, allowing no man to possess his own faculties, or to enjoy the fruit that he has won by their exercise, to call land or house or home his own, allowing no man to do a day's work for another, or to sell and buy on his own account, denying to all men the ownership and possession of either body or mind, necessarily intolerant, as the tsar's government is intolerant, of every form of free thought and free enterprise, trembling at the very shadow of liberty, haunted by the perpetual terror that the old love of self-guidance and free action might some day again awake in the breast of men, obliged to exercise a discipline, like that which exists in the German army, from fear that the first beginning of revolt might prove the destruction of the huge trembling ill-balanced structure, with no sense of right—right a mere word that would be lost to their language—but only the ever-present, ever-urgent necessities of maintaining their unstable power, which was always out of equilibrium, always in danger, because opposed to the essential nature of men—that unconquerable nature, which has always broken and will always break in its own time these systems of bondage. Picture also the horde of countless officials, who would form a bureaucratic, all-powerful army, vast as that which exists in Russia, and probably as corrupt—for the same reason—because only able to fulfill their task, if allowed to have supreme unquestioned power; always engaged in spying, restraining, and repressing, forever monotonously repeating, as if they governed a nursery—“Don't, you mustn't”; and then picture imprisoned under the bureaucratic caste a nation of dispirited ciphers—ciphers, who would be as peevish, discontented and quarrelsome as shut-up children, because shut off by an iron fence from all the stimulating influences of free life, and forbidden, as if it were a crime, to exercise their faculties according to their own interests and inclinations; picture also the intense, the ludicrous pettiness that would run through the whole thing. As a French writer (Leroy Beaulieu) wittily said—it would be a great state question, ever recurring to trouble the safety of the trembling quavering system, whether or no a wife should be allowed to mend the trousers of her husband. Who could exorcise and lay to rest that insoluble problem, for if the wife were once allowed to perform this bit of useful household duty, might not the whole wicked unsocialistic trade of working for others, in return for their sixpences and shillings, come flowing back with irresistible force? Such is the small game that you are obliged to hunt, such are the minute pitiful necessities to which you are obliged to stoop, when once you construct these great state machineries, and take upon yourself, in your amazing and ignorant presumption, to interfere with the natural activities of human existence.

See also another truth. There are few greater injuries that can be inflicted on you than taking out of your hands the great services that supply your wants. Why? Because the healing virtue that belongs to all these great services—education, religion, the winning of land and houses, the securing of greater comfort and refinement and amusement in your lives—lies in the winning of these things for yourselves by your own exertions, through your own skill, your own courage, your friendly cooperation one with another, your integrity in your common dealings, your unconquerable self-reliance and confidence in your own powers of doing. This winning, these efforts, are the great lessons in lifelong education; that lasts from childhood to the grave; and when learned, they are learned not for yourselves alone, but for your children, and your children's children. They are the steps and the only steps up to the higher levels. You can't be carried to those higher levels on the shoulders of others. The politician is like those who boasted to have the keys of earth and heaven in their pocket. Vainest of vain pretenses! The keys both of heaven and earth lie in your own pocket; it is only you—you, the free individuals—who can unlock the great door. All these great wants and services are the means by which we acquire the great qualities which spell victory; they are the means by which we become raised and changed in ourselves, and by which, as we are changed, we change and remake all the circumstances of our lives. Each victory so gained prepares the way for the next victory, and makes that next victory the easier, for we not only have the sense of success in our hearts, but we have begun to acquire the qualities on which it depends. On the other hand the more of his ready-made institutions the politician thrusts upon you, the weaker, the more incapable you become, just because the great qualities are not called out and exercised. Why should they be called out? There is no need for them; their practice ground is taken away; and they simply lie idle, rusting, and at last ceasing to be. Tie up your right hand for three months and what happens? The muscles will have wasted, and your hand will have lost its cunning and its force. So it is with all mental and moral qualities. Given time enough, and a politician with his restless scheming brain and his clumsy hands would enfeeble and spoil a nation of the best and truest workers. He is powerless to help you; he can only stand in your way, and prevent your doing.

Refuse then to put your faith in mere machinery, in party organizations, in acts of Parliament, in great unwieldy systems, which treat good and bad, the careful and the careless, the striving and the indifferent, on the same plan, and which on account of their vast and cumbrous size, their complexity, their official central management, pass entirely out of your control. Refuse to be spoon-fed, drugged and dosed, by the politicians. They are not leading you toward the promised land, but further and further away from it. If the world could be saved by the men of words and the machine makers, it would have been saved long ago. Nothing is easier than to make machinery; you may have any quantity of it on order in a few months. Nothing is easier than to appoint any number of officials. Unluckily the true fight is of another and much sterner kind; and the victory comes of our own climbing of the hills, not by sitting in the plain, with folded hands, watching those others who profess to do our business for us. Do you think it likely or reasonable, do you think it fits in with and agrees with your daily experience of this fighting, working world of ours, that you could take your chair in the politician's shop, and order across his counter so much prosperity and progress and happiness, just as you might order cotton goods by the piece or wheat by the quarter? Be brave and clear-sighted, and face the stern but wholesome truth, that it is only you, you with your own hands, you with your unconquerable resolve, without any dependence on others, without any of these childish and mischievous party struggles, which are perhaps a little more exciting than cricket, or football, or even “bridge” to some of us, but a good deal more profitless to the nation than digging holes in the earth and then filling them up again, without any use of force, without any oppression of each other, without any of these blind reckless attempts to humiliate and defeat those who hold different beliefs from ourselves, and who desire to follow different methods from those which we follow, without any division of the nation into two, three or more hostile camps, ever inspired with dread and hatred of each other—it is only you yourselves, fighting with the good, pure, honest weapons of persuasion and example, of sympathy and friendly cooperation—it is only you, calling out in yourselves the great qualities, and flinging away all the meaner things, the strifes, the hates, the jealousies, the mere love of fighting and conquering—it is only you, treading in the blessed path of peace and freedom, who can bring about the true regeneration of society, and with it the true happiness of your own lives.

And through it all avoid that favorite, that much loved snare of the politician, by which he ever seeks to rivet his hold upon you, refuse to attack and weaken in any manner the full rights of property. You, who are workers, could not inflict on your own selves a more fatal injury. Property is the great and good inducement that will call out your efforts and energies for the remaking of the present form of society. Deprive property of its full value and attractiveness, and we shall all become stuff only fit to make the helpless incapable crowd that the socialist so deeply admires, and hopes so easily to control. But it is not only for the sake of the “magic of property,” its power to call out the qualities of industry and saving; it is above all because you cannot weaken the rights of property without diminishing, without injuring that first and greatest of all possessions—human liberty; it is for that supreme reason that we must resist every attempt of the politician to buy votes by generously giving away the property that does not belong to him. The control of his own property by the individual, and the liberty of the individual can never be separated from each other. They must stand, or fall, together. Property, when earned, is the product of faculties, and results from their free exercise; and, when inherited, represents the full right of a man, free from all imaginary and usurped control of others, to deal as he likes with his own. Destroy the rights of property, and you will also destroy both the material and the moral foundations of liberty. To all men and women, rich or poor, belong their own faculties, and as a consequence, equally belongs to them all that they can honestly gain in free and open competition, through the exercise of those faculties.

It is idle to talk of freedom, and, while the word is on one's lips, to attack property. He who attacks property, joins the camp of those who wish to keep some men in subjection to the will of others. You cannot break down any of the defenses of liberty, you cannot weaken liberty at any one point, without weakening it at all points. Liberty means refusing to allow some men to use the state to compel other men to serve their interests or their opinions; and at whatever point we allow this servitude to exist, we weaken or destroy in men's minds the sacredness of the principle, which must be, as regards all actions, all relations, our universal bond. But it is not only for the sake of liberty—though that is far the greater and higher reason—it is also for the sake of your own material progress—that you, the workers, must resolutely reject all interference with, all mutilations of the rights of property.

For the moment the larger part of existing property belongs to the richer classes; but it will not be so, as soon as ever you, the workers, take out of the hands of the politicians, and into your own hands, the task of carving out your own fortunes. The working body of the people must no longer be content—not for a single day—to be the propertyless class. In every city and town and village they must form their associations for the gaining of property; they must put their irresistible pence and shillings together, so that, step by step, effort upon effort, they may become the owners of land, of farms, of houses, of shops, of mills, and trading ships; they must take shares in the great well-managed trading companies and railways, until the time comes, as their capital increases, when they will be able to become the owners at first of small trading concerns, established by themselves, and then later of larger and more important concerns. They must—for all reasons, the best and the second best—become the owners of property. Without property no class can take its true place in the nation. They must devote much of their resolution and self-denial to the steady persistent heaping together of the pence and shillings for this purpose. As they become possessed of property, they will see a definite goal lying before themselves—one good and useful ambition ever succeeding to another. The old dreary hopelessness will disappear, they will gain in power and influence; the difference between classes will disappear; they will break the enfeebling and corrupting influence of the politicians—what influence would remain to the man of words if he could no longer offer gratis—in return for nothing but votes—the property of others, without any greater exertion on the part of the people than marking their voting papers in his favor? And with the acquiring of property, the workers will also acquire the qualities that the management of property brings with it; while they add a new interest, a new meaning to their lives. We appeal to the many thousands of strong, capable, self-denying men that are to be found among us. Is the gaining of property only a dream; is the thing so very difficult, so far out of your reach? Say that a million men and women begin tomorrow to subscribe one halfpenny a week—who would miss that magical halfpenny, which is to transform so many things?—at the end of the year you will have a fund of over £100,000 to start with—not we think, a bad beginning for the great campaign. In many cases the property, such as land and houses, that you would so acquire, you would probably rent or redistribute on remunerative but easy terms to your own members; in the case of workers in towns, you would be able to allow those of your members who desired rest and change, to work for a time on your farms, and you would also be able to make a holiday ground and common meeting place of some farm that belonged to you, and that could be easily reached by that true instrument of social progress for men and women, the bicycle. Many will be the new forms of health and comfort and amusement that will become possible to you, when once you steadily determine to pile the pence and the shillings together for becoming owners of property; and when once you have put your hand to this good work, you must not relax your efforts until you have become, as you will become before many years have passed, the greatest of property holders in the nation. All is possible to you if you resolutely fling away from you the incitements to strife, the tamperings with liberty and individual property, and pile up the pence and the shillings for the acquiring of your own property. Resist, therefore, all reckless, unthinking appeals made to you to deprive the great prize of any part of its attractions. If you surround property with state restrictions, interfere with free trade and any part of the open market, interfere with free contract, make compulsory arrangements for tenant and landowner, allow the present burdens of rate and tax to discourage ownership and penalize improvements, you will weaken the motives for acquiring property, and blunt the edge of the most powerful material instrument that exists for your own advancement. Only remember—as we have said—that great as is your material interest in safeguarding the rights of individual property, yet higher and greater are and ever will be the moral reasons that forbid our sanctioning any attack upon it, or our suffering state burdens and restrictions and impediments to grow round it. True liberty—as we said—cannot exist apart from the full rights of property; for property is—so to speak—only the crystallized form of free faculties. They take the name of liberty in vain, they do not understand its nature, who would allow the state—or what goes by the name of the state—the worthy eighteen or twenty men who govern us—to play with property. Everything that is surrounded with state restrictions, everything that is state-mutilated, everything taxed and burdened, loses its best value, and can no longer call out our energies and efforts in their full force. Preserve, then, at its best and strongest the magic of property; leave to it all its stimulating and transforming virtues. It is one of the great master keys that open the door to all that in a material sense you rightly and proudly wish to do and to be.

Many other points remain; we can only touch here on a few of them. Keep clear of both political parties, until one of them seriously, earnestly, with deep conviction, pledges itself to the cause of personal liberty. At present they are both of them opportunist, seeking power, rejecting fixed principles. It is true that we owe great debts to the Liberal Party in the past, but at present it is deserting its own best traditions, ceasing to guide and inspire the people, fighting the downhill not the uphill battles, and intent on playing the great game. Someday, as we may hope, it may refind its better self and breathe again the spirit of true exalted leadership, and regardless of its own fortunes for the hours place itself openly on the side of Mr. Spencer's “widest possible liberty.” But today both parties mean anything or nothing; they represent only too often mere scrambling, mere lust for power. It is true that one or other of the two parties may mean to you some of the things that you yourselves mean, but it will also mean a great many things that you do not mean. They both believe in subjecting some men to the will of other men, in using the state as the instrument of universal force, and you cannot rightly take your place in their ranks, or fight with them. Have nothing to do with the scramble for power. Hold on your own course and stand “foursquare to all the winds.” Pick out your boldest and most resolute men, and fight every by-election. Don't fight to win, but fight to teach and inspire. The more resolutely you stand on your own ground, the more men of both parties, who begin to see the worthlessness and the mischief of these party conflicts, and the growing danger of using force, will come to you and join your small army. Few as you are today, you are stronger than the huge ill-assorted crowds—representing many conflicting opinions—that stand opposed to you, for no one can measure the strength that a great and true cause, devotedly followed, gives to those who consistently serve it. Fight the battle of liberty at every point. Give your best help to those who are resisting municipal trading, or resisting interference with home work, or resisting the placing of power in the hands of the medical or any other profession. You must not confer any form of authority or monopoly on any profession; you must not give to any of them the power to force their services upon us. Let every profession that will, organize itself and make rules for its own members; but we, the public, must remain free in every respect to take or to leave what they offer to us. The monopolies that they all so dearly love are fatal to their own efficiency, and to their own higher qualities, as well as full of danger to the public. We all lose our best perceptions, we all become intellectually hidebound, we all begin to believe that the public exist for us, exist for our professional purposes, whenever we are protected by a monopoly. In the same way never hand over any question to be decided but those who are called experts. The knowledge of the experts is very useful and valuable, but wisdom and discernment and well-balanced judgment are different things from knowledge, and they do not always keep company. Knowledge is great, someone has written, but prejudice is greater. The experts are excellent as advisers, but never as authoritative judges, allowed to stand between the public and the questions that affect its interest. The real service that the experts can perform for us is to place their knowledge in the clearest and simplest form before us all, and to explain their reasons for advising a certain course. There is no limit to the mistakes that the most learned men may make when they are allowed to deliver judgment behind closed doors, when they are not called upon to submit their reasons to open discussion, and to justify publicly the counsels that they offer.

Strive also to make this great empire of ours an instrument of help and usefulness and friendliness for the whole world. It is a great world trust placed in our hands, that we must interpret in no selfish and narrow, in no boastful and vainglorious spirit. Cast away all the tawdry and sordid dreams of an empire stronger than all other nations; but let it rest on the one true foundation of peace and friendship, and as far as lies with you of free intercourse between all nations—an empire of equal generous rights, with no privileges reserved for any of us. So, and only so, shall this great empire endure, saved from the fate that has so justly swept away all the other great empires, that were founded on meaner and more selfish conceptions. Have nothing to do with this pitiful cowardly un-English war against the aliens. Even if your interests should seem to suffer for a while—which there is strong reason for believing would not be the case—we ask you to make this sacrifice for the sake of the liberty of all, even the poorest, and for the sake of the proud traditions of our race. Unswerving, disinterested devotion to the principle of universal liberty, and to those noble traditions that have always opened the gates of this country to the suffering and oppressed, will far, far outbalance any hurt that may for a time result from the presence with us of the suffering and oppressed. Plead always that there should be no unworthy exceptions; all such exceptions are bad in themselves, and have the bad habit of becoming the rule. The temper of timorous selfishness that would exclude any aliens, that would treat any natives as different from our own flesh and blood, is our real danger—the danger that threatens our true greatness. Indulge that temper in any one direction, and you will presently encourage it to become the evil genius of the nation.

Last, let us all work together, to soften and improve the relations of capital and labor. War between capital and labor is only too like the unreasonable and disastrous war between nations, or between parties in a nation. All war is a crime, and, as all crimes are, a mischievous folly—in almost all cases a mere outburst of childishness. Everywhere we have to learn the wise art of pulling in friendly forbearing fashion with each other, and not against each other; everywhere we have to learn to abandon the useless wasteful brutal methods of war, and to enter the blessed and fruitful paths of peace. Is there any war of any kind, that might not have been avoided by better temper, more patience, and a stronger love of peace? Is there any war, excepting on very rare occasions the wars to repel invasion or the attacking of great human rights, that in the end has not brought disappointment and sorrow, and bitter fruits of its own, as much or even more to the nation that was successful, as to the nation that was unsuccessful? And who profits from these great labor contests, and the stirring of hurtful passions, that goes with them? Friendship, friendly cooperation, the making of common cause for common ends, are the true ends to be aimed at between labor and capital; and each contest makes the good day of reconciliation more difficult, puts it further and further from us. We cannot choose in this great matter. There is only one way. We must be friends. Nothing less than honest heartfelt friendship will mend the old evils, and make the happier future. As we asked, who profits by these contests? If you—the workers—win today, the capitalists organize themselves tomorrow more strongly than before; if the capitalists win, the workers in the same way strengthen their fighting forces. And so—just as between nations—runs forever the vicious circle. And as with the nations, so our labor strife is not only lost and wasted, but it fatally injures both sides alike—both the conquerors and the conquered. Let us then love and honor peace, cling to her, open our hearts to her, make sacrifices for her, bear and forbear for her sake, place her great ends before everything else, and resolve that, as far as lies with us, her happy reign shall at last be established over the whole land. Peace—always hand in hand with her great sister liberty—not only represents the higher meaning of our moral life, but also like liberty represents the greatest material interest that the workers have; their industry and skill will never bear their full fruits as long as we cling to war, and the destructive methods of force. Capital and labor, like the rest of us, must obey the great moral law and tread in the path of peace and friendship. It is their duty, as it is the duty of all of us in the other relations of life—worthy of every effort, of all patience and sacrifice on our part. Only with peace can the true prosperity come. With peace and friendship, trade and enterprise would develop a much more vigorous life, and find for themselves many new directions. Nothing limits enterprise so fatally, and with it the employment of the workers, as the dissensions and quarrels between capital and labor. With peace and friendship not only does more and more capital flow into trade and production; but new enterprises are confidently undertaken in every direction; and then, as the consequence, wages rise in the one true healthy manner—with the security that peace brings, capital bidding against capital, and the capitalist accepting lower profits. All insecurity, all disturbance of trade relations, must be paid for, and they are paid for by the worker; for insecurity and uncertainty mean that a higher rate of profit is necessary to tempt the investment of capital lying idle, and therefore necessarily results in lower wages.

Reorganize then your trade societies on a peace basis, or establish new unions on that basis. Preserve your independence; but do all in your power to enter into friendly alliances with capital. Remember that friendship is the triumph of good sense and wise temper; strife is the indulgence of the undisciplined, the childish part of our nature. Form associations in which both the workers and the capitalists would be represented; where they would meet and take common action, as friends, working together to make the conditions of labor better, more comfortable, more sanitary, and using every peace expedient to remove difficulties as they arise. If times of depression come, and wages fall low, use the common fund to draft away some of the workers, find temporary employment for them on the farms and lands that you will acquire as your own, start workshops of your own, which in some cases might provide articles of home use and comfort for your members; and let your unemployed members in turn receive a grant to enable them to spend their unoccupied time usefully in study and education. At present an unoccupied workman wastes time and temper during a slack time. Like his own tools he rusts and deteriorates with them. Why should that be so? Have your own classes and day schools, and let the unoccupied men turn the time to golden use. But through it all, even if you strike, refuse as a matter of principle, as faithful followers of liberty in everything, to use any of the old bad methods of force. If, after every effort, after attempting mediation and arbitration, you cannot agree about wages with the employers, and if you think it wise and right and necessary to do so, throw up your work; but if there are those who will take the wage that you are unwilling to take—let them do so, without let or hindrance. It is their right; and we must never deny or fight against a human right for the sake of what seems to be our interest of the moment. We say what “seems” to be; for in the end you will gain far more by clinging faithfully to the methods of peace and respect for the rights of others than by allowing yourselves to use the force that always calls out force in reply, always brings its own far-reaching hurtful consequences, for the sake of the advantage or victory of the moment. Once be tempted to use force, and force will become your master, your tyrant, tempting you again and again to seek its aid and to enter its service. No man employs force today without being easily persuaded to use it once more tomorrow, and then again the next day. There are in all that we do only two ways—the way of peace and cooperation, the way of force and strife. Can you hesitate between them? Do not good sense and right sense plead for the one and against he other? Set yourselves then to discover and practice every conciliatory method; wherever practicable, become shareowners and partners in the concerns where you labor, and make it your pride to join hands frankly with the employers, wiping out forever the old disastrous war feeling, that has brought so much useless suffering and loss with it.