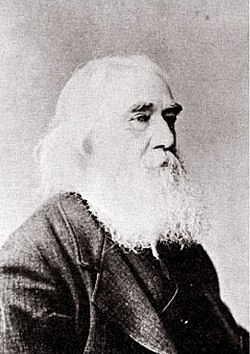

Lysander Spooner (January 19, 1808)

by Peter Mentzel

This month’s featured birthday anniversary is the American political philosopher and abolitionist activist Lysander Spooner. He occupies an important place in the history of American individualist thought, and was crucially important in the development of a uniquely American understanding of Anarchism.

Spooner was born on a farm near the town of Athol, Massachusetts, the second of nine children. Little is known about his parents or family, or even his early life. The farm families in the area were characterized by a flinty, hard-working ethic. His father, Asa (1778-18551), was, somewhat unusually for the local culture, known to be a Deist, an attribute he passed on to his son Lysander. His mother, Dolly Brown Spooner (1784-1845), was loved and even idolized by her son Lysander. Both parents were avid abolitionists, another view they passed on to their son. When he was 25 He left the family farm and secured work with the office of Deeds and Records in Worcester, Massachusetts. He soon came to the attention of a local lawyer and politician John Davis (1787-1854) who hired him to work at his law firm in 1833. Davis was at the time pursuing a political career with the Whigs that would eventually see him elected governor of Massachusetts and then to multiple terms in the Senate (where he emerged as a consistent voice against slavery and an opponent of the Mexican War). Davis was very impressed with young Spooner’s abilities and urged him to go into the law. This launched one of Spooner’s very first struggles against established authority, as he rebelled against the licensing laws of the time that, in his view, discriminated against poorer applicants. He successfully fought the regulations, with Davis’ help, and became an attorney in 1836. Shortly thereafter he engaged in a disastrous episode of real estate speculation in the Ohio River Valley, exacerbated by the Panic of 1837. Following that debacle, he spent a brief period back on the family farm, following which he moved to New York, and then to Boston.

His next major act of rebellion against authority was the establishment of his own postal service, a reaction against what he saw as the outrageous rates and poor service of the US Post Office. His company, the American Letter Mail Company, established in 1844 (and accompanied by a descriptive pamphlet), was so successful that it drew the attention of the authorities who, using all manner of coercive strategies, drove him out of business in 1851.

In the meantime, the question of slavery became increasingly intense nationally, and Spooner turned his abolitionist background to the fight against it, an early example being his 1850 pamphlet against the fugitive slave law. In contrast to the dominant Garrisonians, however, who preached that the US Constitution was a “covenant with death and an agreement with hell” because of its support of slavery, Spooner developed a startlingly original and sophisticated argument (in his “The Unconstitutionality of Slavery” 1860) that the Constitution does not, in fact, condone slavery. His arguments were tremendously attractive to many abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass, who broke with the Garrisonians over the issue. Spooner’s abolitionist writings and attitudes became increasingly radical, including a plan, published in 1858, to arm slaves and assist them in fomenting an uprising.

After the Civil War, the Emancipation Proclamation, and the ratification of the thirteenth amendment, however, Spooner became increasingly disillusioned by what he saw as the tremendous growth in the power of Federal Government. This led to the publication of two extended essays, together entitled No Treason (1867, 1870) in which he makes a bold argument against the legitimacy of the US Constitution and, by implication, the authority of the US national government itself. During this period he also became increasingly concerned about the economic and social dislocations caused by the rapid industrialization of parts of the country, including his native New England. While a consistent supporter of the rights of private property, Spooner developed a deep suspicion of the growing powers and wealth of bankers and industrialists, and the potential threats these posed to the freedom of individual working men and women.

He also continued to publish on broader legal themes including the importance of jury nullification and personal freedoms. The latter was the subject of a powerful and (typically) controversial essay “Vices are Not Crimes: A Vindication of Moral Liberty” (1875) His final work (1886) was a scathing attack against the growing power of the national government, which he framed as an open letter to President Grover Cleveland.

In the midst of his prodigious publications, he continued to eke out a living as a practicing attorney, but in general we know almost nothing about Spooner’s personal life. He lived for years in a small apartment at 109 Myrtle Street, near the Boston Athenaeum, where he did much of his writing. We know of one serious love affair in 1855 with a teacher named Mary Booth. While his surviving letters to her suggest that he was very deeply in love, she broke off the relationship, possibly because of Spooner’s poverty. We know of two other affairs, one with a medium named Lizzie Doten in 1860, and another, in the 1870s, with Virginia Vaughn, a lecturer on poetry, but neither seem to have developed into anything serious.

While Spooner never called himself an anarchist, he was clearly part of the strong American individualist tradition resting on an understanding of Natural Law which also sustained such American individualist anarchists as Josiah Warren (1778-1874), Steven Pearl Andrews (1812-1886) and, especially, Benjamin Tucker (1854-1939) who became one of Spooner’s deepest admirers and supporters. Lysander Spooner died on May 14, 1887 and was buried in Forest Hills Cemetery, Boston.