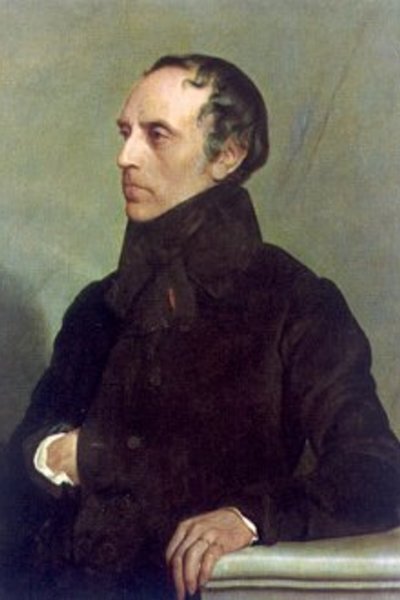

François Guizot (1787-1874)

Source: François Guizot, General History of Civilization in Europe by François Pierre Guillaume Guizot, edited, with critical and supplementary notes, by George Wells Knight (New York: D Appleton and Co., 1896). Chapter: BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH.

Copyright: The text is in the public domain.

Fair Use: This material is put online to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. Unless otherwise stated in the Copyright Information section above, this material may be used freely for educational and academic purposes. It may not be used in any way for profit.

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH.

François Pierre Guillaume Guizot was born of Protestant parentage at Nîmes, France, on October 4, 1787. His father, a prominent advocate, became a victim of the French Revolution during the Reign of Terror, dying on the scaffold in 1794. Madame Guizot removed to Geneva, where her son received a classical education under Protestant influences. It is stated that before he left Geneva, at the age of eighteen, he was able to read Greek, Latin, German, Italian, and English. Spanish he learned when he was seventy-two years of age, in order that he might write a history of Spain. In 1805 he removed to Paris to enter upon the study of law. He soon obtained a position as tutor in the family of M. Stapfer, the Swiss minister to France, supporting himself in this way while pursuing his studies. The study of law he soon abandoned for literary and historical work. Within a few years he began writing for the press, his first articles appearing in Le Publiciste, then controlled by M. Suard. Through his connection with M. Suard he became acquainted with Mademoiselle Pauline de Meulan, who was also a contributor to the paper. Though she was fourteen years his senior, their common occupation and mutual tastes led to their marriage in 1812. M. Guizot published in 1809 a dictionary of French synonyms, in 1810 an essay on the Fine Arts in France, and in 1813 an annotated translation of Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. In 1812 he was chosen assistant professor of history in the Faculty of Letters at the Sorbonne in Paris, and a little later was made professor of modern history. His professorship gave him the acquaintance of M. Royer-Collard, then professor of philosophy at the Sorbonne, to whom he was indebted for his first public position under the later restored government of Louis XVIII. His writings during this period were mainly philosophical and literary. Politically he was an advocate of legitimate monarchy as against Napoleon, and desired the restoration of the Bourbons, with such constitutional limitations as would secure the rights of the people against the recurrence of prerevolutionary absolutism.

In 1814, on the downfall of Napoleon, he was given the position of Secretary-General in the Department of the Interior under the monarchy of Louis XVIII. After the return of Napoleon, the Hundred Days, and the second restoration of Louis XVIII, he became Secretary-General of the Department of Justice, and in 1817 was made a member of the Council of State, and Director-General of the departmental and communal administration. He was identified at this time with the political party or faction known as the Doctrinaires, of which M. Royer-Collard was a prominent exponent. This group desired constitutional monarchy based on suffrage in the hands of the middle classes; they were thus opposed on the one hand to the radical democratic spirit growing out of the Revolution, and on the other to the growing absolutism of Louis XVIII and his court. During this period he wrote several political pamphlets in exposition of these general views.

In 1820 the royalist reaction consequent upon the murder of the Duc de Berri caused the downfall of the ministry, and Guizot resigned all his offices. He immediately resumed his lectures at the Sorbonne. It was at this time that he delivered the celebrated course of lectures on the History of Representative Government. His lectures and writings did not accord with the reactionary spirit of the reign of Charles X, and in 1825 he was forbidden to continue his lectures. During the next few years he was active among the opposition to the policy of the government, but devoted himself principally to historical writing. In rapid succession he published a collection of Memoirs on the English Revolution, Memoirs relating to the History of France, and an Introduction to a revised translation of Shakespeare. The most important work was the History of the English Revolution, of which only the first two volumes were completed at this time.

In 1825 his wife died, and in the following year he married Mademoiselle Dillon, the niece of his first wife. In 1828, upon a change of the ministry, M. Guizot was restored to his professorial chair. In that year he delivered the lectures on the History of Civilization in Europe which form the present volume; in the following year he gave a course on the History of Civilization in France. These lectures not only attracted immediate attention, but they marked an epoch in historical writing. The careful research, the profundity of reasoning, the skill and rapidity of generalization, and the breadth of view displayed take these lectures out of the rank of ordinary historical productions. The influence of the spirit in which M. Guizot undertook the consideration of historical material and of the development of political institutions was unquestionably productive of an important result upon historical method. From this time forth, in the intervals of political service and after his retirement from public life, he gave himself to historical writing in the broad, scholarly, philosophical spirit which he here displayed.

In 1830 he was elected to the Chamber of Deputies, and from that time until 1848 he was almost constantly engaged in public position. He took a prominent part in the protest against the arbitrary acts of Charles X which led to the July Revolution of 1830, and to the accession of Louis Philippe to the throne of the French. Under the new government M. Guizot was made Provisional Minister of the Interior, but retired after a short incumbency. In 1832, under the ministry of Marshal Soult, he became Minister of Public Instruction. He reorganized the work of public instruction in France, and originated and carried through the Chambers the law of June 28, 1833, which was the basis of the system of popular primary instruction that was rapidly extended over France. Into all the details of organizing this work the minister went with the most careful attention and interest, furnishing to the directors, subordinates, and teachers kindly instructions which show in every phase his deep concern in the work. Secondary and higher instruction also received careful attention.

In 1836 the ministry fell, and Guizot retired from his position, retaining his seat in the Chamber of Deputies. In 1840 he was sent to England as ambassador, where he was warmly welcomed because of his literary reputation, his admiration for the British Constitution, and his friendliness for England in the then existing European situation. In the same year he was recalled, and on October 29th became Minister of Foreign Affairs. Until 1848 he was the real head of the ministry. His policy was the maintenance of constitutional government at home, against the radical tendencies of the Republicans, and peace abroad, against the war-loving spirit of the French people.

In the latter part of his ministry he yielded more and more to the king, and was led to meet the rising spirit of democracy and the cry for electoral reform by measures that were reactionary and extraconstitutional, if not unconstitutional. His devotion to law and order were at this time transforming him into an ultra-conservative. In 1848 the ministry fell, and with it the monarchy of Louis Philippe. During the eight years of its continuance the ministry of which Guizot was the chief spirit gave peace and prosperity to France; industry and commerce flourished; popular instruction was improved; the penal code was revised, and internal improvements on a large scale undertaken. The ministry failed, largely because of Guizot’s lack of knowledge and appreciation of the practical side of political and governmental life. He was of the closet, not of the people, and in the zeal of his Doctrinaire policy he failed to appreciate the necessity of keeping in fairly close touch with popular feeling. Concession of principle he could never make, and by refusing to yield anything to the opposition, he, and the monarchy whose destinies he was seeking to guide, lost all.

After the Revolution of 1848 he retired to England, and, with the exception of a single unsuccessful candidacy for the Chamber of Deputies, never again took part in French politics. In 1851 he returned to France, and spent the remaining twenty-three years of his life in literary pursuits on his estate at Val Richer, in Normandy. While in England, he wrote and published the History of the English Republic and the Protectorate of Cromwell, and later the History of the Protectorate of Richard Cromwell and the Restoration of the Stuarts. These two works completed the history begun in 1827. He also wrote during this period of his life the Memoirs on the History of My Own Times; Meditations on the Christian Religion; History of France for my Grandchildren (completed by his daughter, Madame Guizot De Witt), and several other historical and philosophical essays and books.

His most celebrated and best-known works are the History of Representative Government, History of Civilization in Europe, and History of Civilization in France. He was elected in 1832 to the Academy of Moral and Political Science; in 1833, to that of Inscriptions and Belles-Lettres; and in 1836, to the French Academy, the highest literary honor in France. He died at his home, September 13, 1874, at the age of eighty-six.

The character of M. Guizot was such as to place him among the foremost men of the century. He is conspicuous among public men for the purity of his private life and for his simple, honest Christian belief. As a statesman he attained a high rank; he was a fairly consistent and unswerving advocate of constitutional monarchy, but lacked the practical force and knowledge requisite for the highest success in a field where pure theory must often yield to the attainable.

His fame will always rest chiefly on his historical writings. His style was clear and attractive; his knowledge of facts wide and accurate; his analysis of historical forces clear and sharp; his generalizations and conclusions remarkably sound and well-founded. His early and constant devotion to the cause of constitutional monarchy colored all his political writing, and accounts in the present course of lectures for many of the positions that can hardly be accepted with the full and unqualified application with which they are stated by the author. Nevertheless, his historical works will always command the careful consideration of the student, and will hold for him a place among the foremost historical writers of modern times.

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE.

The list of general works given below will be helpful in the further study of matters touched upon in this work. No attempt has been made to include works not readily accessible, and the list is merely suggestive, not exhaustive. Authorities upon special fields and subjects are not included here, but, where needed, are given in the notes.

- Adams, G. B. Civilization during the Middle Ages. New York, 1894.

- Andrews, E. B. Brief Institutes of General History. Boston, 1887. Contains good bibliographies.

- Bryce, James. The Holy Roman Empire. London and New York.

- Church, R. W. The Beginnings of the Middle Ages. London, 1882.

- Duruy, V. A History of France. Abridged and translated from the French. New York, 1889.

- Duruy, V. The History of the Middle Ages, with notes and revisions by George B. Adams. New York, 1891.

- Duruy, V. History of Modern Times. Translated from the French. New York, 1894.

- Emerton, E. An Introduction to the Study of the Middle Ages (375-814). Boston, 1888.

- Emerton, E. Mediæval Europe (814-1300). Boston, 1895.

- Fisher, G. P. History of the Christian Church. New York, 1887.

- Fisher, G. P. Outlines of Universal History. New York, 1885. Contains good bibliographies.

- Gibbon, Edward. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. 5 to 8 volumes. Numerous editions.

- Guizot, F. P. G. History of Civilization in France. 4 volumes.

- Hallam, Henry. View of the State of Europe during the Middle Ages. 3 volumes. Numerous editions.

- Henderson, E. F. Select Historical Documents of the Middle Ages. 1892.

- Hodgkin, Thomas. Italy and her Invaders. Oxford, 1880—’85.

- Kitchin, G. W. History of France. 3 volumes. Oxford, 1873—’77.

- Mathews, Shailer. Select Mediæval Documents illustrating the History of Church and Empire. 1892.

- Menzel, W. History of Germany. 3 volumes. London.

- Milman, II. II. History of Latin Christianity. 8 volumes.

- Möller, W. History of the Christian Church. Translated from the German. 3 volumes. 1892—’94.

- Myers, P. V. N. Outlines of Mediæval and Modern History. Boston, 1885.

- Ploetz, Carl. Epitome of Ancient, Mediæval, and Modern History. Translated with extensive additions by William H. Tillinghast. Boston, 1883.

- Ranke, L. History of the Popes. 3 volumes. London.

- De Sismondi, J. C. L. Italian Republics. London, 1835.

- Stillé, C. J. Studies in Mediæval History. Philadelphia, 1883.

- Translations and Reprints from the Original Sources of European History. Edited by J. H. Robinson. Philadelphia, 1895.