Tracts on Liberty by the Levellers and their Critics Vol. 1 (1638-1643) (2nd ed)

Tracts on Liberty by the Levellers and their Critics, Volume 1 (1638–1643)

(2nd. revised and enlarged Edition)

[Note: This is a work in progress]

Revised: 25 May, 2018.

In vol. 1 (1638-43) there are 42 titles (36 corrected):

- 11 from the 1st edition all of which have been corrected

- 11 titles which appear elsewhere on the OLL and have been corrected but need rechecking

- 20 additional titles of which 14 have been corrected

Note: As corrections are made to the files, they will be made here first (the “Pages” section of the OLL </pages/leveller-tracts-summary>)) and then when completed the entire volume will be added to the main OLL collection (the “Titles” section of the OLL) </titles/2595>.

- Tracts which have not yet been corrected are indicated [UNCORRECTED] and the illegible words are marked as &illegible;. Some tracts have hundreds of illegible words and characters.

- As they are corrected against the facsimile version we indicate it with the date [CORRECTED - 03.03.16]. Where the text cannot be deciphered it is marked [Editor: illegible word].

- When a tract is composed of separate parts we indicate this where possible in the Table of Contents.

For more information see:

- Summary of the Leveller Tracts Project </pages/leveller-tracts-summary>

- The Complete Table of Contents </pages/leveller-tracts-table-of-contents>

Table of Contents

-

Introductory Matter (to be added later)

- Introduction to the Series

- Publishing and Biographical Information

- Copyright and Fair Use Statement

-

Editorial Matter (to be added later)

- Editor’s Introduction to Volume 1 (1638-1643)

- Chronology of Key Events

- Tracts in Volume 1 (1638-1643)

- [CORRECTED - July 2014 - 5 illegibles] T.2 [1638.??] (1.2) John Liburne, A Light for the Ignorant (1638).

- [CORRECTED - Sept. 2014 - 2 illegibles]T.3 [1638.??] (1.3) John Liburne, A Worke of the Beast (1638).

- The Publisher to the Reader

- A WORKE OF THE BEAST, OR A Relation of a most unchristian Censure, executed vpon IOHN LILBVRNE

- Lilburne’s poem "I Doe not feare the face nor power of any mortall man"

- [CORRECTED - Sept. 2014] T.1 [1638.03.12] (1.1) John Liburne, The Christian Mans Triall (12 March 1638, 2nd ed. December 1641).

- [CORRECTED - 06.01.16 - 10 illegibles] T.4 [1640.??] (8.1) John Selden, A Brief Discourse concerning the Power of the Peeres (1640).

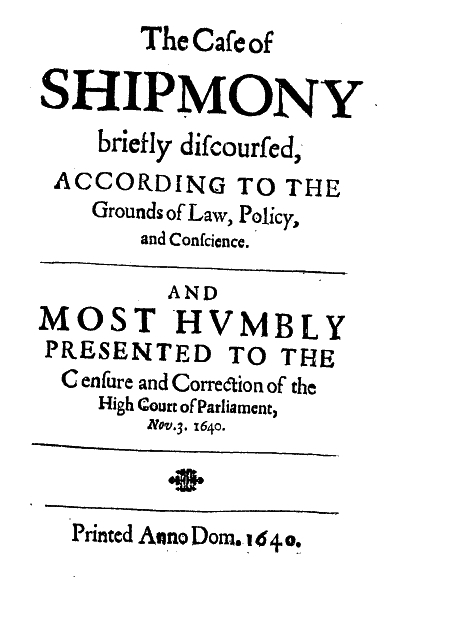

- [CORRECTED - 04.02.16] T.282 [1640.11.3] (M1) Henry Parker, The Case of Shipmoney briefly discoursed (3 Nov. 1640)

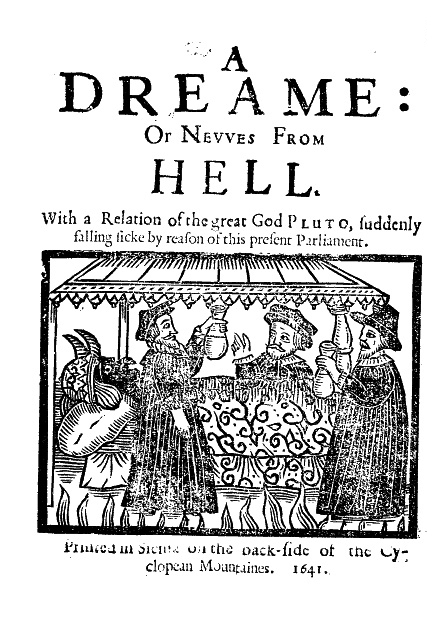

- [CORRECTED - 18.12.15 - 5 illegibles] T.5 [1641.??] (10.1) [Richard Overton], A Dreame, or Newes from Hell (1641).

- [CORRECTED - 06.01.16 - 1 illegible] T.6 [1641.??] (8.2) John Davies, An Answer to those Printed Papers by the late Patentees of Salt (1641).

- [CORRECTED - 06.01.16]T.283 [1641.04.12] (M2) John Pym, The Speech or Declaration of John Pym (12 April, 1641)

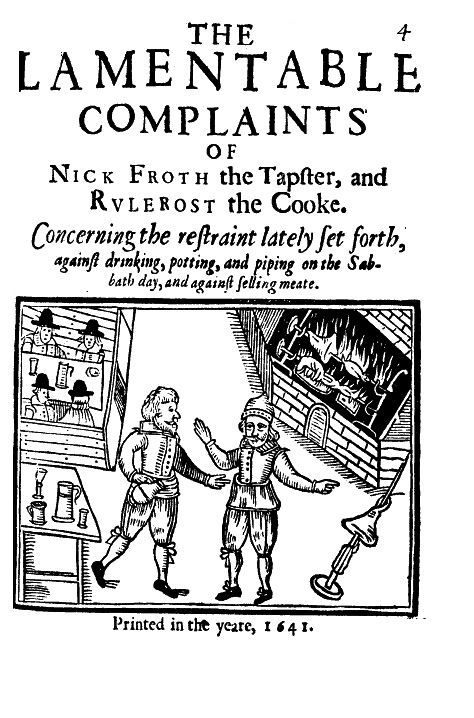

- [CORRECTED - 03.03.16]T.7 [1641.05] (8.3) Anon., The Lamentable Complaints of Nick Froth the Tapster (May 1641). [INTRO - 03.07.16]

- [CORRECTED - 06.01.16] T.260 [1641.05] John Milton, Of Reformation Touching Church Discipline in England (May, 1641).

- [CORRECTED - 06.01.16] T.261 [1641.06] John Milton, Of Prelatical Episcopacy (June or July, 1641).

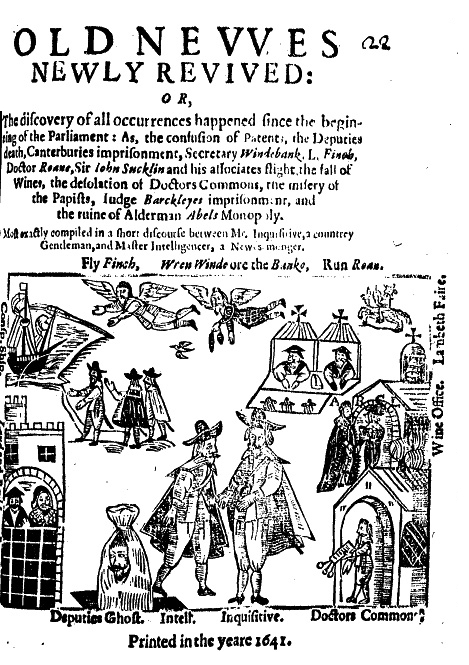

- [CORRECTED - 18.12.15 - 2 illegibles]T.8 [1641.06] (10.2) [Richard Overton or John Taylor], Old Newes newly Revived (June 1641).

- [CORRECTED - 06.01.16] T.262 [1641.07] John Milton, Animadversions upon The Remonstrants Defence against Smectymnuus (July, 1641).

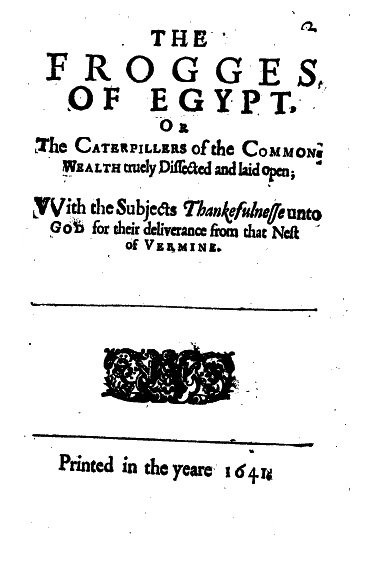

- [CORRECTED - 18.12.15 - 2 illegibles ]T.9 [1641.08] (10.3) [Richard Overton], The Frogges of Egypt, or the Caterpillers of the Commonwealth (August, 1641).

- The Frogs of Egypt

- Poem: A Thanksfullness to God for his Mercy towards this KINGDOME

- [CORRECTED - Sept. 2014]T.10 [1641.09] (1.4) [William Walwyn], A New Petition of the Papists (September 1641).

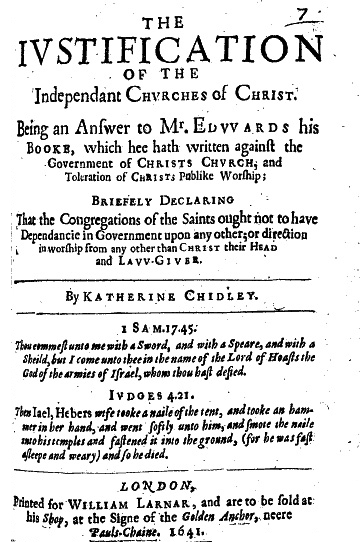

- [UNCORRECTED - 31 illegibles] T.11 [1641.10] (8.4) Katherine Chidley, The Justification of the Independant Churches of Christ (October, 1641).

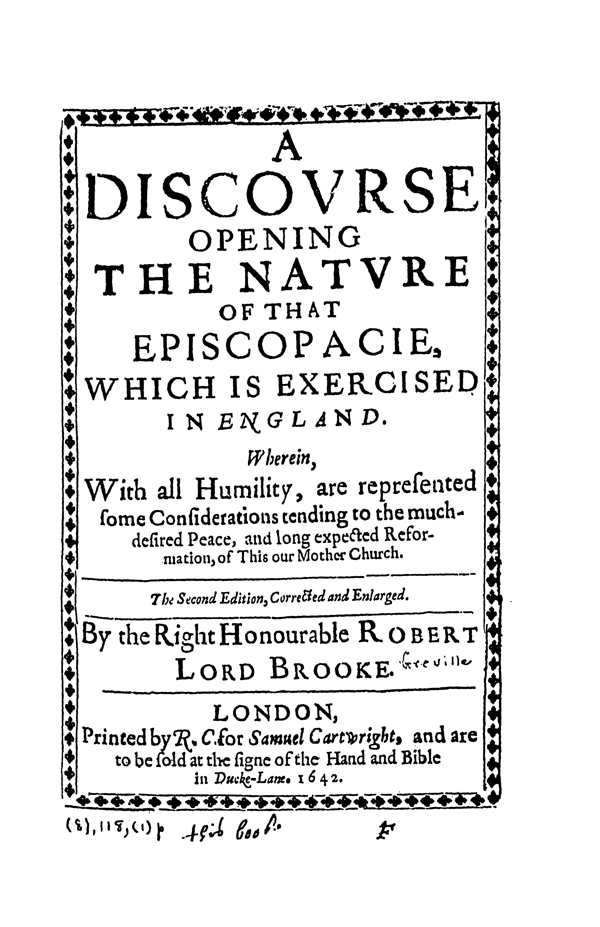

- [CORRECTED - Sept. 2014 - 10 illegibles]T.12 [1641.11] (1.5) Robert Greville, A Discourse opening the Nature of that Episcopacie (November 1641).

- [PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED - NEED TO RECHECK] T.263 [1642.01] John Milton, The Reason of Church-Government Urged against Prelaty (Jan. or Feb., 1642).

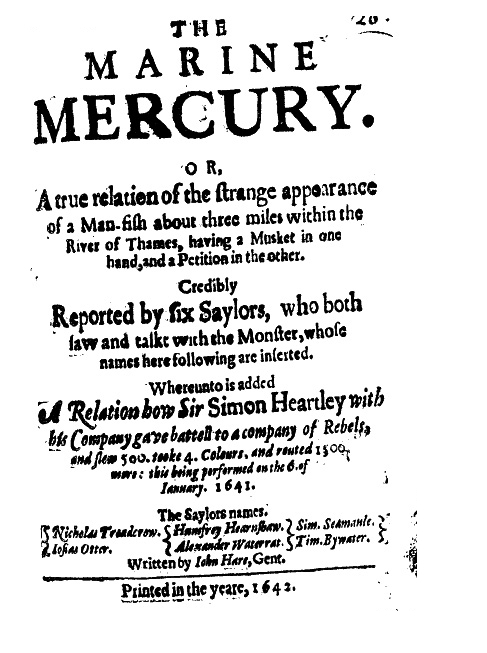

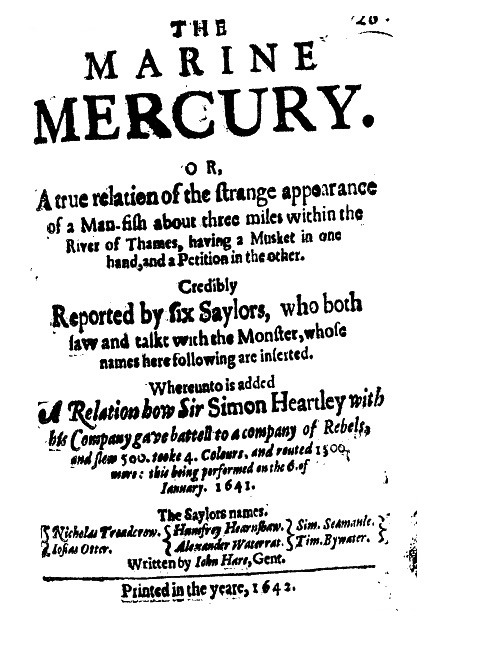

- [CORRECTED - 26 Jan. 2016 - 0 illegibles]T.13 [1642.01.06] (8.5). John Hare, The Marine Mercury (6 January, 1642).

- [PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED - NEED TO RECHECK] T.264 [1642.04] John Milton, An Apology against a Pamphlet (for Smectymnuus) (April, 1642).

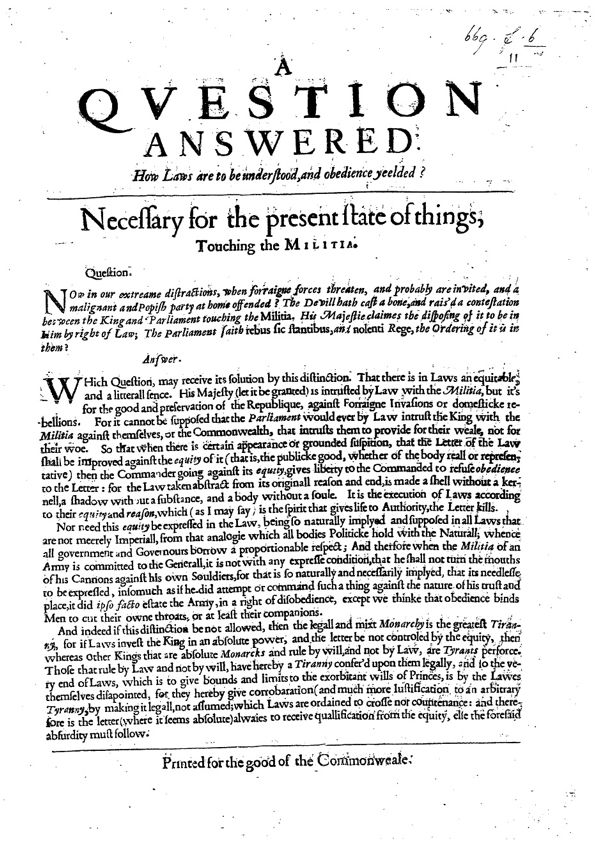

- [CORRECTED - 26 Jan. 2016 - 0 illegibles] T.14 [1642.04.21] (8.6) Anon., A Question Answered (21 April, 1642).

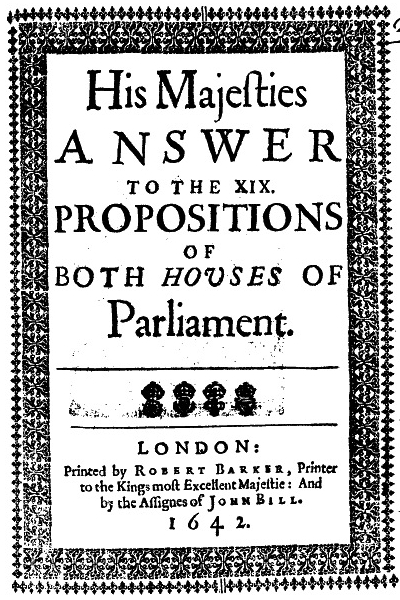

- [RECHECKED - 26 Jan. 2016 - 0 illegibles]T.284 [1642.06.18] (M3) Charles I, His Majesties Answer to XIX Propositions made by both Houses of Parliament (18 June, 1642)

- [CORRECTED - 18.12.15 - 7 illegibles]T.15 [1642.07.02] (1.6) Henry Parker, Observations upon some of his Majesties late Answers and Expresses (2 July 1642).

- [PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED - RECHECKED 13.11.2017]T.285 [1642.08??] (M4) Henry Ferne, The Resolving of Conscience upon this Question (Autumn 1642)

- [CORRECTED - 15.11.2017 - 103 illegibles]T.16 [1642.09.30] (8.7) John Marsh, The Great Question concerning the Militia (30 September, 1642).

- [CORRECTED - 26.01.2018 - 21 illegibles]T.17 [1642.10.15] (8.8) Richard Ward, The Vindication of the Parliament (15 October, 1642).

- [CORRECTED - 17.02.15 - 9 illegibles]T.18 [1642.10.12] (1.7) John Goodwin, Anti-Cavalierism (21 October, 1642).

- [CORRECTED - 17.02.15]T.19 [1642.11.10] (1.8) [William Walwyn], Some Considerations Tending to the Undeceiving (10 November 1642).

- [UNCORRECTED - 110 illegibles] T.20 [1642.11.26] (8.9) Richard Ward, The Anatomy of Warre (26 November, 1642).

- [UNCORRECTED - 31 illegibles] T.21 [1642.12.06] (8.10) William Prynne, A Vindication of Psalme 105.15 (6 December, 1642).

- [PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED - NEED TO RECHECK] T.286 [1642.12.29] (M5) Charles Herle, A Fuller Answer to a Treatise written by Doctor Ferne (29 Dec. 1642)

- [UNCORRECTED - 6 illegibles] T.22 [1642.12.31] (8.11). Anon., The Privileges of the House of Commons (31 December, 1642).

- [CORRECTED - 21.01.16 - 8 illegibles] T.23 [1643.01.17] (8.12) John Norton, The Miseries of War (17 January, 1643).

- [CORRECTED - 21.01.16 - 3 illegibles] T.24 [1643.01.24] (8.13) Anon., The Actors Remonstrance (24 January, 1643).

- [CORRECTED - 21.01.16 - 31 illegibles] T.25 [1643.02.24] (8.14) Anon., Touching the Fundamentall Lawes of this Kingdome (24 February, 1643).

- [CORRECTED - 23.02.15 - 572 illegibles] T.26 [1643.04.15] (1.9) William Prynne, The Soveraigne Power of Parliaments and Kingdomes (15 April 1643).

- [UNCORRECTED - 1 illegible] T.27 [1643.05.19] (8.15) Anon., Briefe Collections out of Magna Charta (19 May, 1643).

- [UNCORRECTED - 42 illegibles] T.28 [1643.05.24] (8.16) Philip Hunton, A Treatise of Monarchy (24 May, 1643).

- [UNCORRECTED - 167 illegibles] T.29 [1643.06.14] (8.17) Anon., The Subject of Supremacie (14 June, 1643).

- [PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED - NEED TO RECHECK] T.265 [1643.08] John Milton, The Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce (August, 1643).

- [CORRECTED - 27.02.15] T.30 [1643.09.19] (1.10) [William Walwyn], The Power of Love (19 September 1643).

- [CORRECTED - 02.03.15 - 239 illegibles] T.31 [1643.10.07] (1.11) William Prynne, An Humble Remonstrance against The Tax of Ship-money (7 October 1643).

- To the Reader

- AN HUMBLE REMONSTRANCE To His MAJESTY AGAINST THE TAX OF SHIP-MONEY NOW IMPOSED

- THE OPENING OF The Great Seale OF ENGLAND

- The Kings and Parliaments Severall and joint Interests in, and power over the new-making, keeping, ordering of the Great Seale of England

- The Votes of the House of Commons, together with their reasons for the making of a new Great Seale of England, presented by them to the Lords at a Conference, Iuly 4. & 5. Anno 1643.

Introductory Matter↩

[Insert here]:

- intro image and quote

- Publishing History

- Introduction to the Series

- Publishing and Biographical Information

- Key to the Naming and Numbering of the Tracts

- Copyright and Fair Use Statement

- Further Reading and info

Key (revised 21 April 2016)↩

T.78 [1646.10.12] (3.18) Richard Overton, An Arrow against all Tyrants and Tyranny (12 October 1646).

Tract number; sorting ID number based on date of publication or acquisition by Thomason; volume number and location in 1st edition; author; abbreviated title; approximate date of publication according to Thomason.

- T = The unique “Tract number” in our collection.

- When the month of publication is not known it is indicated thus, 1638.??, and the item is placed at the top of the list for that year.

- If the author is not known but authorship is commonly attributed by scholars, it is indicated thus, [Lilburne].

- Some tracts are well known and are sometimes referred to by another name, such as [“The Petition of March”].

- For jointly written documents the authoriship is attributed to "Several Hands".

- Anon. means anonymous

- some tracts are made up of several separate parts which are indicated as sub-headings in the ToC

- The dating of some Tracts is uncertain because the Old Calendar (O.S.) was still in use.

- (1.6) - this indicates that the tract was the sixth tract in the original vol. 1 of the collection.

- Tracts which have not yet been corrected are indicated [UNCORRECTED] and the illegible words are marked as &illegible;. Some tracts have hundreds of illegible words and characters.

- As they are corrected against the facsimile version we indicate it with the date [CORRECTED - 03.03.16]. Where the text cannot be deciphered it is marked [Editor: illegible word].

- After the corrections have been made to the XML we wil put the corrected version online in the main OLL collection (the “Titles” section).

- [elsewhere in OLL] the document can be found in another book elsewhere on the OLL website.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement↩

The texts are in the public domain.

This material is put online to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. Unless otherwise stated in the Copyright Information section, this material may be used freely for educational and academic purposes. It may not be used in any way for profit.

Editorial Matter↩

[Insert here]:

- Editor’s Introduction to this volume

- Chronology of Key Events for this year.

Tracts from 1638-1643 (Volume 1)

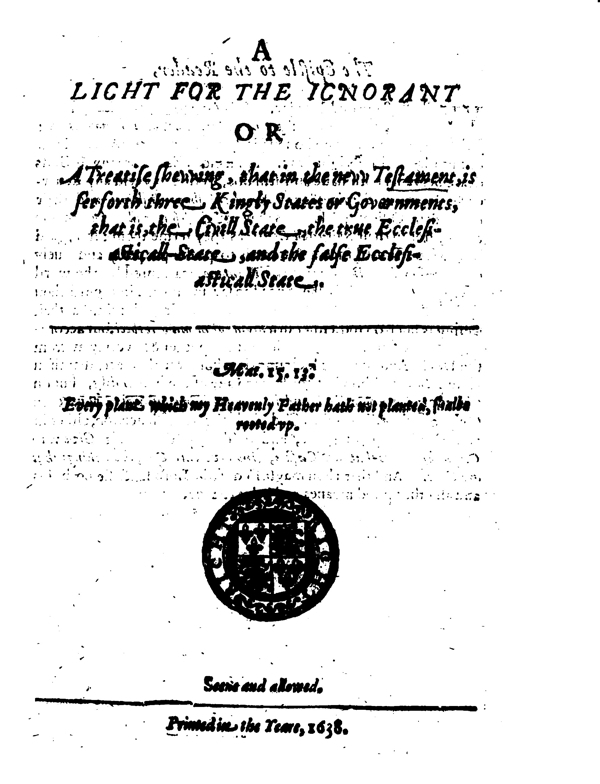

T.2 (1.2.) John Lilburne, A Light for the Ignorant (1638).↩

Editing History

- Illegibles corrected: HTML (date)

- Illegibles corrected: XML (date)

- Introduction: date

- Draft online: date

Bibliographical Information

ID NumberT.2 [1638.??] (1.2) John Liburne, A Light for the Ignorant (1638).

Full titleJohn Lilburne, A Light for the Ignorant or A Treatise shewing, that in the new Testament, is set forth three Kingly States or Governments, that is, the Civill State, the true Ecclesiasticall State, and the false Ecclesiasticall State.

Mat. 15.13. Every plant which my Heavenly Father hath planted shall be rooted up.

Seene and allowed, Printed in the yeare, 1638.

Estimated date of publication1638 (no month given).

Thomason Tracts Catalog informationNot listed in TT.

Editor’s Introduction

(Placeholder: Text will be added later.)

Text of Pamphlet

The Epistle to the Reader,

VVell affectionated Reader. It is (as thou knowest) a divine precept, that we should giue Honour to whom honour is due: Jmplying therein, that no honour is due either to Persons or things, but in a lawfull and right way. And hence it is that many of Gods deare Servants both haue and still doe, refuse to yeeld any Reuerence, Honoor, Service, &c. vnto Archbishops Bishops: and their dependent Offices; I say, as they are Ecclesiasticall persons & doe administer in their Spirituall Courts as they terme them: in regard they have assumed such a State as is to speake properly and truely of it, neither Iure Divino nor jure Humano, warrented by the word of God. But of this I shall not need to say any more, in regard thou shalt find what here I say cleared & proved sufficiently: viz. that their calling is not from God, either in a divine or humane respect, but according to the scripturs after mentioned: altogether & every way from the Devill. And therfore look unto it whosoever thou art, that thou (like Mordecay) bow not the knee to any of these Amaleks, but on the contrarie Feare God and honour the King, and give reverence Only to such ordinances as God binds thy Conscience too, either in respect of nature or grace, and soe doeing thou shalt Give vnto Cæsar the things that are Cæsars, And give vnto God, those things that are Gods. And that thou mayst so doe, the Lord sanctifie both this and all other good meanes and helps to thee.

A LIGHT FOR THE IGNORANT OR A Treatise shevving, that in the nevv Testament, is set forth three Kingly States or Governments, that is, the Civill State, the true Ecclesiasticall-State, and the false Ecclesiasticall State.

THere are in the new Testement of Christ Iesus three Kinglie States or Governments. The Civill State. The true Ecclesiasticall State. And the false Ecclesiasticall State. Two of them are of God, and the third is of the Divill. They all consist of these Seven particulars following.

In the First, place these three pollitique Regiments hath each of them a King or Head over them.

Secondly, They haue each of them authoritie power or state pollitique.

Thirdly, They haue books and Charters, wherein their statutes, Lawes, and Cannons are writen.

Fourthly, Each of these make themselves Citties Corporations or bodies politique.

Fiftly, They haue Officers and deputies who are their seuerall Ministers to and in there bodies or Corporations.

Sixtly, They have Lawes, ordinances, and administrations for these officers to administer to their subjects, according to there severall functions in the name and by the power of their proper King, and head; from whom they haue received their authority & in whose name they administer.

Sevenlie, and lastlie, they haue subjects or members governed by and in their seuerall pollitique States and powers vnder their severall beads.

The First particular Handled.

These haue each of them a King or Head over them.

The Civill State.

The First is the State of Magistracie or civill State, that wherein Cesar is to haue his due as King and head, these Kings & heads are to be prayed for of all Gods people, as their Heads and gouernours Rom. 13. 1. 2 1. Tom. 2. 2.

The true Ecclesiasticall State:

This state is Christs the annointed Psa. 2. 6. Acts. 2. 26. whome God the Father hath set upon the Throne of David, Jsay, 9. 6. 7. and he is King of Saints Rev. 15, 3. Yea the King of Kings & Lord of Lords. Rev. 17. 14. & 19, 16.

The False Ecclesiasticall State.

The third is the helish state of the Beast, his Kingdome or state of Rome, which in the 13. Rev. v. 2. is said to haue his power from the Devill; also he is said to haue a Throne: therefore hee is a King 11. c. He is called the King of the Locusts which is there said to bee the Angell of the bottomleste pit. v. 11.

Secondly, these haue each of them a Kingly state or power pollitique

The Civill State.

This power or Civill state is of God, and is the Charracter of Gods soveraigntie over man; is displaid by his Communicating the same unto Kings & such as are in authority under them, for which cause hee hath said yee are Gods; and God must and is obeyed by stooping and submitting to this power and state, and he that resisteth this power resisteth the ordinance of God Rom. 13. c.

The true Ecclesiasticall State.

Likewise this state is of God; for it is the Kingdome of his deare Sonne, & is not the Civill state but the Ecclesiastical state of Christ his Church, or power which he received of his Father Mat 28. 18, after that he rose again from the dead, by which power he authorised his Apostles & sent them on his errand or message to al the world, Mat. 28. which power the Apostles vsed in planting Churchs and Church Officers, which power Christ gives to all the Churches of the Saints to the end of the world, it is the power given to them to bind and loose too, and from the Devill, and to right each others wrongs Mat. 18. it is the same power and state the Churches had comitted to them by the Apostles who reproved the Churches for not using it to suppresse sinne and sinners 1 Cor. 5. with the seuen Churches in Asia. Rev. 2. 3. c. these and many more are the severall vses the Lord hath made of this true Ecclesiasticall or Church state, and Goverment.

The False Ecclesiasticall State.

This Angell of the Bottemlesse pit Rev. 9. 11. the King of the Locusts hath a state, throne, power, and great authority. Rev. 13. 2. & in the same Chapter it is said, he hath power to continue 42 moneths, v. 5. that is 126. dayes as c. 12. 6. counting each day for a yeare (as the Lord doth in numbers, 14. 34. and Ezec. 4. 6,) it is 1260. yeares that is the length or time of his Raigne, that one and the same time which Christs Kingdome vnder the name of the holie City shal be trod under foot Rev. 11. 2. Likewise that is that power or state that the woman or great whore sits or aids uppon: whereby shee is able to Raigne Rev. 13. 16. & c. 17. as a Queene over the Kings of the earth. And Lastly, this state is soe great that it Captiuates all Kings Princes & Emperours, yea all the world of vngodly men Rev. 13. 7. 8. wonders, followes; and worships this state, or beast, and if they will not he hath such power and authority that hee will compell high and low, rich and poore, bond and free, to submit unto him, & to kill all those that are found refractory to his state and power. Rev. 13. 15. 16. 17. This is the False Ecclesiasticall state and power.

Thirdly, these haue each of them bookes and Charters to declare their minds to their Subjects.

The Civill State.

Thirdly, all Kings & governours haue Bookes, statutes, and Records, wherein are recorded their Lawes Articles, Acts of Parliament, likewise to Citties and townes Corporated they give Chartors whereby they haue power and preuilidge from their King, & head, in his name and power to instate themselves into divers previledges for their mutuall good.

The true Ecclesiasticall State.

Even soe in the next place Christ Jesus hath given his lawes vnto Iacob & his statutes to Israell, his statute Books are the Holie Scripture of the Old and New Testament, he is faithfull in all his house as was Moses Heb. 3. 2. 6. the acts of his last Parliament which hee called for the establishing of his Kingdome, when hee was 40. daies with his Disciples giving them lawes through the Holy Ghost, even till hee was taken vp into Heaven in their sight, as wee may see in Acts. 1. chapt. Those bookes called the Acts of the Apostles, with-all the Epistles and the Revelation, in these the Cities and Charters of the new Jerusalem is to be found with the previledges thereunto belonging.

The False Ecclesiasticall State.

This smoaky pollitique State of the Crowned Locusts or Roman Clergie Rev. 9. 3. 7. hath distinct bookes from the other two states that are of God, for this State or power hath Bookes of Cannons, Counsels; bookes of Articles, bookes of Ordination of Priests and Deacons; with the booke of Homilies, and the Booke of Common-prayer, and the power and state of this Beast, doth more narrowly looke that all be agreeable to these bookes then the other two states doth (as is manifest by that strict eye that is had ouer all in every parish) not onelie in forraigne Lands, but even in this our Kingdome of England, for they of this Kingdome of Darkenesse are wiser & more diligent in their generation them the children of light.

Fourthly, by vertue of these Charters, these three states make Citties and Corporations, according to their proper & distinct state & power pollitique.

The Civill State.

In the next place the loyall Subjects of this Regiment vnder their King & Head, by vertue of these Charters, become famous Citties, & other inferior corporations agreeable to the tenour of their severall Charters that they received from their Head, & when they received their Charters then & by that means they received the State & power to become a Citty or Corperation vnder that Head, & when they haue vnited or incorporated themselvs into a Bodie they are a Citty constituted, and this state & power they are entered into, is their for me and being, and nothing else doth distinguish them from their former state and condition but that power and state, that is, their state wherein they live moue and haue their being pollitiquely.

The true Ecclesiasticall State.

In like manner the Subjects of this heavenlie regiment or King dome of Christ, by power from him their Head, doe become visible Churches and bodies incorporated together in his name & power Mat. 18. therefore the Church hee left behind him of 120. were of one accord Acts 1. and to them were vnited or joyned 3000. in the next chapt. so the saints at Antioch, became a body or Church whose constitution or incorporation wee may see to bee a joyning themselves to the Lord Acts. 1. 2. 23. soe all the Churches of the Saints became bodies pollitique, and therefore Gods visible Churches are called Citties or the City of God Psal. 46. 4. Psal. 48. 1. 2. 8. & Psal. 87. 2. 3. Therefore the Saints are called Cittizens Ephes. 2. 19. Inhabitants of the Living God Heb. 12. 22. This holy Cittie is troden under foote 42. Moneths Re. 11. 2. the time of the Raigne of the Beast (Re. 13. 5.) whose Raigne is just so long & this Holy Citty is the new Jerusalem that comes downe from heaven in great glory Rev. 21. the forme or beeing of his divine Citty or spirituall Bodie is the state and power pollitique instituted by Christ and given to his Saints Jude, 3. v. Psal. 133. and thus under Christ as their King they live, moue and haue their being pollitiquelie.

The False Ecclesiasticall State.

So the power of Satan the Devil by hath the wisdome of the second Beast, or false Propher, not only made to himselfe a great Citty whose power killed Christ Rev. 11. 8. Thereby pointing vs to the Roman power that still kills his Saints, for this Citty is soe powerfull that she Raigns over the Kings of the earth, & maks them to drinke of the cup of her fornications, till they be so drunke thereby that they become her servants Rev. 17. 2. 18. & 18. 2. And by this false Ecclesiasticall power & state, there are made lesse Citties called the Citties of the nations of (nation Churches) & are of the same nature Re. 16. 9. as Daughters to the whore & Mother of fornication of the earth, this false great Catholique Church is distributed into nations, provinces, and into every diocesse and parrish, as liuely and apparent as the Civill state, is in every parrish and in every House therein, soe that they live moue and haue their beeing as Royallie from this Beastlike power as the Saints doe by Christ, or subjects under their King, this is plaine by the daily troubles the poore saints suffer in every parrish if they worship not as this power commands.

Fiftly These haue each of them proper and distinct officers belonging to each pollitique State.

The Civill State.

In the first place these Cities by vertue of their Chartors, injoy their owne officers, Majors, Shirrifes, Alderman, and other inferiour Officers as their Lord and King hath allotted them, and also inferiour corporations according as is granted to them in their Chartor, and they that obey these doe well and please God in keeping the first Commandement.

The true Ecclesiasticall State.

Likewise the Citty of God by vertue of their chartor haue right to enjoy their owne Bishops, ouerseeres or Elders Acts, 14. 23. and chap, 20. Titus, 1. 5. 7. Which are not many, yet Wisdome that hath built her house hath found them to be sufficient: which are these, Pastors, Teachers, Elders, Deacons, Widdowes, Rom. 12. 7. 8. Ephe. 4.-11. 12. Phi. 1. 1. 1 Tim. and they that obey these and these onely serve Christ and obey God in keeping the 2. and 3. Commandements, these only being the officers which God by his Holy Apostles hath set up, instituted and placed in his Church to the end of the world: therefore, in Hearing, and obeying these we heare & obey Christ that sent them Luke. 10. 16. Math. 10. 40.

The False Ecclesiasticall State.

In like manner hath this whorith City, or Citties, the False Prophet, or Body of false prophets attending upon their forged divises, & humane administrations, which are almost innumirable to reckon from the Pope to the parish clark or Parstor whosoever obyes these or any of these breaks the three first Commandements, for in hearing & obeying these they hear & obey the Dragon, Beast, & whore, that sent them and gaue them their authority and Office, that as Realie as wee Heare and obey the King by stooping and submitting to a Constable who sees not this.

These haue each of them proper and severall lawes, statutes, ordinances, and administrations for their severall officers to attend vpon.

The Civill State.

Sixtly, In this state or in these Citties are the lawes and ordinances of men, that the saints must obey in the Lord, for though in the time of Christ and his Apostels there were no Christian Kings, yet the Churches of the Saints were commanded to obey their Lawes, Religious Lawes they could not bee, Because the Magistrates were all infidells, therefore the Apostle Peter distingusheth them from the Divine, by calling them the Ordinances of men, due vnto Caesar as divine obedience is unto God,

The true Ecclesiastcall State.

Even so this Cittie of God with their officers are to obserue what soever Christ hath commanded them Math. 28. 20. the Church of Corinth kept them 1 Cor. 11. 2. and Paulls Charge to Timothy is to teach the Church to obserue all without prefering one before another, as he would answer it before Christ Iesus and his Elect Angells. These divine things are due to Christ Iesus, and to him & to him onely, belongs this visible worship Ioh. 4 21. 22. 23.

The false Ecclesiasticall State.

The Lawes & administrations of this whorish Church, are partly their owne Inventions, contained in the Bookes formerly named, with some divine truthes which vsurped they injoy, which truthes they vse as, a help to set a glose vpon their inventions: that they may passe with a better acceptation but both Divine and devised are consecrated & dedicated by the Beast, and are administred by his Officers and power.

Seauentlhy, All these three haue their subjects or people which their pollitique Bodies consist of.

The Civill State.

Lastly, this State hath Subjects, which are the Kings alleiged people, and are bound to him their Head, by the Oath of alleigence, & as any of them do purchase a Charter from him to become a Cittie or Corporation, they are bound by vertue of their Charters to walke submissiuely to him their pollitique head, and in that relation are by duty bound to keepe the Lawes of their Charters in his name & power, which is their pollitique obedience.

This Ciuill State is Gods Ordinance, and is here borrowed to Jllustrate, manifest, and set forth the other two in the former perticuler, and soe we leaue it.

The true Ecclesiasticall State,

Soe in the last place, the Subjects of this State are only Saints & noe other, that is such as by the Rule of the word are to be Judged one of another to be in Christ, otherwise they haue no right to this Kingdome 1 Cor. 4. 20. Chapt. 5. 13. But are intruders lud. 4. verse and soe not of the Kingdome, though in the Kingdome, 1 Iohn 2. 19 and the Saints are out of their places till they come within this Holy Citty.

To this State all Gods people are Called, both out of this world and all false Churches, especially from this Regiment of darkenesse there discribed 2. Cor. 6. 17. & Rev. 18. 4.

The False Ecclesiasticall State,

Lastly, the Subjects of this Kingdome of darkenes are all the Inbabitans of the Earth, Kings & subjects Rev. 13. 16. & Chap. 18. 3. Yea it, hath a commanding power, bond and free, to receive a mark of subjection and servitude, there is none soe bad but will serve his turne, if any proue too good hee casts them out, kills and destroys Rev. 11. 7.

This is the State and Kingdome of darkenes: with which the Devill hath deluded all nations from which all Gods people & Servants are bound in duty to seperate, that soe they may bee free from that wrath of God which shall fall upon the Kingdome of the beast to the Ruine & ouerthrow thereof Rev. 18. 4. 5. & 19. 20. & 14. 9. 10, 11.

Leaving the premises let every one note these ensuing differences or disproportions, that are betwene the Ecclesiasticall States, for thir different natures.

The true Ecclesiasticall State

The First disproportion betweene the true and False State is, in the Originall from whence they arise. The true State came from Heaven and is the house of wisdomes building Pro. 9. 1. wherin the sonne of God, the wisedome of his Father, Heb. 1. 3. hath beene as faithfull as was Moses in the former Heb. 3. 2. 6. & is that Heaven discribed Rev. 12. 1. and that Citty said to come downe from Heaven Rev. 21, and is an habitation for God to dwell in, and for all his people to come into: to dwell with God their Saviour, for the name of the Citty is, the Lord is there Ezec. last Chap. and last ver.

The False Ecclesiasticall State.

Likewise it is no hard Mistery to know the Originall of this False Ecclesiastical State, for the Clargie, (as Goodwins Catologue of Bishops Fox his Booke of martyrs, & Rev. 9. & 13 ch.) & by their Preaching & writing hath taught vs plainly that Antichrist the man of sinne, the sonne of perdition is seated in Rome, & the same Clergy doth also teach us: that their Ministery & Goverments of Bishops & Arch Bb. successiuely proceedes from thence, & for our confirmation here in we read that Gregory the first of that name, Pope of Rome about 1000 yeares since, sent Austin the Monke into Englund & consecrated him first Arch B. of Canterbury, and he consecrated the rest of the Bb. and established the Ecclesiastical state, which state & platforme remaines vnaltered to this day; notwithstanding the Head thereof be changed. This state then being the man of sinne, it is said to arise out of the Bottomles pitt Rev. 9. 1. & is called the King of the Locusts Rev. 9. 11. & is said to come by the effectuall working of Sathan 2 Thess. 2. 9. and as he is the sonne of perdition v. 3. and the Mistery of Iniquity v. 7. so shall he come to confusion by the mouth of the Lord v. 8. & go to perdition Rev. 17. 8. as the sonne & heire thereof, & he shall haue the company of his Fatther the great Dragon the Devill and Satan, with the yonger Brother the False Prophet, that deceiued them that worshipped him, these three shall dwell in the tormenting lake of Gods wrath forever and evermore Rev. 19. 20. & 20. 10. And thus wee see Originally from whence hee came and whither he must goe.

The true Ecclesiasticall State,

A Second disproportion is betweene the true power and the false. The true power which Christ our King hath received of his Father Math. 28. 18. and hath comunicated to his Saints 1 Cor. 5. 4, 12. and Psal. 119. and to them onely; This is that Dominion that the Antient of dayes hath giuen to his Saints Dan. 7. 14. compared with ver. 22. 27: and with Revel. 5. 10. & being lost hee will recover it againe vnto them as Daniell speakes, & in the New Testament is giuen to every Particuler visible Church or Assembly of Saints Math. 18. 17. 19. 20. and 1 Cor. 5. 12. In which point of Power, we are to note two things. Fust the Subject or place where it doth recide, that is in the Body or Assembly of the Saints, as the former scriptures largely declare. Secondly, that they were not forced nor compelled to submitt to their power, but as the loue of God shed abroade in their hearts, & the Doctrine of the Apostles by the power of the spirit caused them freely and willingly to submit themselves unto it Acts 2. 41. for Christ and his Apostles never used any means to bring his saints into his Kingdome.

The False Ecclesiasticall State.

Soe in Like manner the Dragon that Old Serpent Rev. 12. [Editor: illegible word] gave to his son of perdition the Beast, his power & throne & great authority Rev. 13. 2. And this man of sinne hath conveyed to all his Clergie his power; by vertue wherof, they are all rulers & men of authority in all nations where he hath established them, as is declared Rev. 9 Chapter & 10 First Verse: wher it is said, they haue Crownes upon their heads like gold, that is counterfit power and authoritie, & by vertue of this power pollitique; are made one intire body pollitique, under one head & King soe called vers. 11. and are distinct from the Layety, living in & by the practise of this power, with reference to that Head, though they bee never soe farre disperced or remote from him; this beeing observed, the disproportion will appeare in these two particulers.

First, the subject place where this power doth recide, it beeing in the body of the Clergy, the Layety being excluded though never so high or great in place, as Iudges, Iustices, Lords & Knights &c, they refusing it as a matter not belonging to them, but to the Clergy.

Secondly, this power compells all in all nations, will they nill they to come under this Government, and to obey his power and authority Rev. 13, 8. 16. where it is said, he made all great and small, rich and poore, free and bond, to submit to him, else they should not buy, nor sell nor live ver. 17. and ch. 11. 7.

The true Ecclesiasticall State:

A Third disproportion shall appeare in this, Every Kingdome or pollitique state whether Civill or Ecclesiasticall, hath their severall bookes and Charters: wherein is contayned the Platforme of there severall governments, soe every Church is knowne by its owne articles, Cannons, and Constitutions, so that they that will know what Church, Ministery and worship Christ and his Apostles hath planted in the new Testement after the Ceremoniall was abolished; they must read the Acts of the Apostles with the Epistles Acts, 6. 4. 1. Cor. 14. 37. Revel. 22. 18. 19. Yea the whole new Testement, and there they shall finde Jesus Christ our Lord and King, his Bookes of Cannons, Articles and Ordination, to guide and direct the Churches of the saints in his Kingdome vnto the end of the world.

The False Ecclesiasticall State

Also in the False State, they that would know what goverment, Church, Ministery, and worship, the man of sinne hath established, he must viewe his Platforme contayned in his Booke of Cannons, Articles, and Ordintion of the Priests & Deacons, his Bookes of homilies and Common Prayers, for in them is contayned those institutions, Lawes and ordinances that he hath established, but how contrary to the Scriptures of the Old and New Testement; they that are Spirituall in part doe know, and how obedience to them is inforced and divine Lawes omitted and laid aside, the poore saints doe finde, and [Editor: illegible word] to there smart.

The true Ecclesiasticall State

A Fourth Disproportion. This State makes not Nationall nor Provinciall pollitique Bodies, but only particuler Congregations or assemblies of Saints, as in Judea one Nation; yet divers Churches Gal. 1. 22. Soe Galatia one nation yet many Churches ver. 3. likewise Asia hath seaven seuerall Churches ver. 1. 11. and where there was but one the Holighost speakes in the singuler number, as the Church at Rome, another at Corinth, another at Collossia, another at Thessalonica, and the like.

Secondly, the Congregations of our Lord Christ come freely and willingly as so many living stones 1 Pet. 2. 4. 5. volluntarily vniting themselues together, whereby they become A Spirituall house and a Royall Priesthood ver. 9. and are hereby capable of performing the publique worship of the New Testament, wherein they are to offer as Living sacrifices their Soules and Bodies Rom. 12. 1. and by faith to haue Communion with their Mediator Heb. 12. 24. as he hath promised to all such assemblies gathered in his name and power Rev. 21. 3. Math. 18. 19. 20. which is the forme and beeing of this their visible and pollitique vnion & communion Eph. 2. 20. 21. 22. Coll. 2. 19. Thirdly, the visible Churches of Christ are independent Bodies; there is Equallity or apparity amongst them: that is, they are all a like in Iurisdiction & authority, they are all Golden Candlestickes Rev. 1. 20. they are every one of them a Ierusalem compact together within it selfe Psal. 122. 3. compared with Heb. 12. 22. hauing each of them whole Christ for their mediatour, that is, Priest, Prophet; and King; and thereby enjoy all his power and all his promises, and all his Lawes and ordinances, with all his liberties and previledges.

Fourthly and Lastly; in the vse of their liberty which they enjoy from and vnder Christ their Head, and dwels in the whole body, in the vse whereof they are inabled to exclude sinne and sinners and ought that offends God or them, 1. Cor. 5. 13. 2 Thes. 3. 14 Acts 3. and to establish among them such Officers, Ordinances, and Admistrations as their Lord & King hath given them for their comfort and profit, by this power they can examine and try False teachers Rev. 2. 2. they can reproue and admonish proud ones and exhort the negligent Cor. 4. 17, thus their power and liberty from Christ their head, becomes a great benefit and a great good to the whole body, in these and divers others perticulers of great weight.

The False Ecclesiasticall State.

But this False State brings ten Kingdomes into one pollitique body Rev. 17. 12. 13. 15. & hath set heads over nations to bring them into pollitique bodies Ecclesiasticall, as for example, England is one pollitique body Ecclesiasticall, (as well as Civil) vnder one Arch-Bishop of Canterbury, and Pope of Lambeth, and by the sinewes and bonds of his Ecclesiasticall power the whole hand as one body is knitt and bound to that Ecclesiasticall Head, by vertue of that Romish authority that hee successively doth exercise, and hath received from Austin the Monke, who consecrated, authorized & sent into this Land to establish this power according to Pope Gregorius his will wisdome and power.

Farther, this False State hath left noe liberty nor power to any person good or bad Rev. 13. 7. 8. but compels and forces all in the name and power of Antichrists successours; will they nill they, haue they faith or no, conscience or no conscience, this beast will be served and obeyed of all states degrees and conditions, of all people in the world ver. 15. 16. 17. soe that there is noe Ecclesiasticall body of his making whether it be the great Catholique Babylon, Revel. 16. 19. or Nationall, or Provinciall; or Perrochiall bodies, but this Beast first made or framed them, and still by the force of the same authority doth compell them to assemble and worship in his name and power, which power is the tome and being of their visible & pollitique vnion and Communion.

Againe the visible Churches which are in the Kingdome of the Beast, are neither independent nor free bodies, therefore the great Citty is called by the Holy ghost; Sodome & Egypt: for her filthynes & bondage Rev. 11. 8. so that there hath not in Europe one parrish beene found free from spirituall Egyptian bondage inflicted upon them by some taske Master of the Clergy, as the Person and Church-Wardens, who force and drive (by spirituall tyranny ouer the consciences of men) to their falsely so called spirituall Courts, to whom they are in bondage, and vpon whom they do essencially depend, & so are not independent, neither haue they any power, or liberty to procure truth or abandon Errour in their publicke worship.

And Lastly, these poore Captiuated slavish assemblies haue noe liberty or power of Christ among them; but a great power ouer them that keepes them in a spirituall bondage, and there assemblies consists of sinners of all sorts, for they haue noe power of reproving or excluding sinne or sinners, they must take such officers as the Bishops sends them be they never soe bad; and they have noe power to exclude or refuse them, and if they proue good they haue no power to keepe them neyther, canne they keepe themselves there, except they submit to, and practise such ordinances, Lawes & administration, as are the inventions of men and will worship, and so breake the second commandement, so that they haue no power to do themselves any spirituall good, or to exclude from themselves any spirituall evill or hurt, but being injoyned by there spirituall taske-masters to assemble to Church, they goe, and when they present them to their Courts, they runne, & being commanded to do this or that in there publick worship, they doe it, though it bee contrary to God and there own consciences. In these and divers other particulers this power, that is ouer them is to their exceding great hurt & damage.

The true Ecclesiasticall State.

The Fift Disproportionly sin their Officers or ministers, which we are to observe thus.

First in there number, Christ Iesus our Lord and King hath instituted and ordayned onely siue; which are specified Rom. 12. 7. 8. Phil. 1. 1. 1 Tim. 5. for though our Lord hath ordained in his Church for the Foundation thereof; himselfe being the Chiefe corner stone, Apostles, Prophets, and Evangelists, yet not successivelie continued; but these Five onelie are to continue to the End of the world.

Secondly, these Officers and Ministers of Iesus Christ, haue not onely there authority from the particuler congregation, but do originally and naturally arise out of the same Acts, 1. 23, 26, and 6. 3; & 14. 23. Note that in the new Translation the word Election is left out of the 23. verse. For before there be any Officers in the Church there is instituted by the Holy Ghost divine offices; functions or odministrations; as voyd and empty roomes. Psa. 122. 5. Rev. 4. 4, & cha. 20. 4. for the saints which dwell in that Citty of God to supply with fit & able persons, to performe those severall administrations, which God hath ordayned and commanded them, and for the authorising of their Officers, they haue Christ walking amongst them as in one of his golden Candlesticks, holding them in the right hand of his Kingly authority, Rev. 1. 16. by these divine deputies he rules them as a King, teacheth them as a Prophet, and feedes them as a Priest with his most sacred body and bloud.

The false Ecclesiasticall State.

But the officers of this false state are the whole body of the Clergy almost innumerable if we should reckon their severall orders & distinction of degres, as Pope, Cardinals, Patriarchs, Primates, Metrapolitans, Arch-bishops, Lord-bishops, Deanes, Chancellars, Vicar-Generals, Praebendes, Arch-deacons, Subdeacons, Doctors, of the Civill Law, Doctors of Divinity, Proctors Registers, Cannons, Petty-Cannons, Chanters, Preists, Iesuits, Parish-Preists, Parsons, Vicars, Curats, Deacons, Vestremen, Church Wardens, Swornemen, Sidemen, Parish Clarks, Sextons, Pursonants, Summinours, Apparitors, with a-multitude more which would tire a man to reckon them al up their being well nie sixscore in all of this rabble, and as Iesus Christ & his Apostles never knew them nor approvedly spoke of them, but rather gave warning to the Saints that they should take heede of such, for such were to come 2 Pet. 2. 1. Mat. 24. 24. and the Saints haue wofull experience that they are come: for they haue been plagued with them this thousand yeares & more, Yet the time approcheth and is neere when they shall bee consumed with the Breath of his mouth and brightnesse of his comming 2 Thess. 2. 8, that rides vpon the white Horse Rev. 19. 11, 12, 15, for their Kingdome is momentary, and his is Everlasting.

Likewise these offices rise not out of the particuler assemblies, neither haue the assemblies any offices or functions, properly in them nor any power or authority to produce or raise officers out of them selves, for the Clergy are a perticuler body distinct from the Layety hauing their consecrations; Offices and authority from and amongst themselves, and soe sent by their Ecclesiasticall Heads, and bring their Office and authority with them, as matters not belonging to the assemblyes, and so by vertue of that Ecclesiasticall power rule ouer them as Lords and teacheth them as that power allowes, and commands them, vsurpedly administreth spirituall foode vnto them, and soe by Imitation beguileth the simple and affronts the Administration of the mediatourship of Christ Iesus.

The true Ecclesiasticall State.

A Sixt Disproportion is the difference betweene there Lawes and Administrations, as euery Citty and Corporation haue there Lawes amongst themselues by vertue of their Charters from their King, Even soe hath every [Editor: illegible word] Church from Christ there King, by vertue of their Charter, which is the New Testament, in possession amongst themselves all Lawes & ordinances as Christ by his Apostles Mat. 28. 20. hath committed to them, Charging them vnder acurse to keep from adding or diminishing to or from these divine Lawes Act. 1. 2. 2. 1 Cor. 1 1. 3. 2 Thes. 2. 15 Rev. 22. 18. 19.

Secondly, as the difference is great in the number of there Officers, the true being few & the False being innumerable, so of necesity must the difference be in the lawes and administrations agreeable to the number of Officers; which particulers I must omitt as a matter to large for this place, yet note this by the way: that one of the first laws in Christs Church is the ordinance of Prophecie 1 Cor. 14. 1. to the end of the chap. that is, that it is not only the liberty, but the duty of every man in the Church that is able to teach & preach to the edifying of the body, so to do (provided he keep the proposition of faith; that is the boundes of his owne knowledge Rom. 12. 6.

The False Ecclesiasticall State.

But as hath beene formerly said; the false Church hath no power nor Charter nor office, for all these things are locked up within the body of the Clergie, soe is it as true that they are distitute of all lawes or administrations, amongst themselves, so that all they haue at any time is brought to them by these Crowned Stinging messengers of that authority, as Commonsence and reason proveth: that the Clergie being apollitique and distinct body of themselves from the Layety; hauing all power and authority Ecclesiasticall in themselues, must of necessity haue all lawes ordinances and administrations in themselves, whether they bee divine, (which they haue by vsurpatõ) or humane, by their own Inventiõ, they only posesse them and haue power to vse them not fearing adding, or detracting, the Lay congregations being altogether passive herein til their Jnjuntion make them active.

Soe the lawes and ordinances of this state being innumerable (as their officers are) J must omit for to name them, as their severall false holy things: Kneeling in the & of receiving, Signeing with, the Crosse in Baptisme, Churching of women, Reading Prayers, with the Consecrating of Dayes, Times, Places, Persons, Garments, with their Anoynting of the Sicke and unholy. Orders of consecration, with other innumerable inventions, not worthy a-place in Christians thoughts, onely note the opposition of their law against the law of Christ, in vehement prohibiting and strongly barring all (Lay men as they call them) from preaching, that let Christ giue never soe great abillities or guifts to lay men: they are never suffered to make any publique vse of them, but it is horrible prophanesse and sacrelegious presumption soe to doe, and this prohibition of the Clergie is and hath been so vniuersall: that it reacheth to the foure Corners of the earth, and with holdeth this spirituall winde of Christ Jesus in the mouth of his Saints that it shall not blow upon them that are in the earth Revel. 7.

The true Ecclesiasticall State

A Sevevth Disproportion is betwixt their subjects or members, the subjects or members of Christs Kingdome or Church must, be beleeving Disciples, they must bee Saints by Calling & sanctified in Christ Iesus 1 Cor. 1. 2. they must be liuing stones to build his house withall 1 Pet. 2. 5. such as these and these onely are enjoyned to observes whatsoever he commands them, to these only is his Kingdome and dominion given, these be they that are crowned as Kings, anoynted as Priests, the mediatour himselfe being theirs, & he hath committed the administration of his mediatorship in his Church to them. But to the Wicked saith God, what hast thou to do with these things. Psa 50. 16. Thou hast not a wedding garment therefore binde him hand & foote & cast him out as leaven dangerous to hurt the body 1 Cor. 5. 7. For without shall be & dogges inchanters and those that loue & make lyes Rev. 22. 15. But within there shall be noe vncleane thing. Revel. 21. 27.

The False Ecclesiasticall State.

But the Subjects of this foule body are all vncleane and hatefull birds, Revel. 18. 2. the Cage that holds them being the Ecclesiasticall state of Rome, is become the habitations of Devils & the hold of every foul spirit, so that the vnfittests members which they can least indure or suffer amongst them, are the conscious saints, they are the soonest turned out, cut of and killed by them Revel. 13. 15, but yet if the saints; or Christ himselfe can by temptations or compulsion bee drawn to worship the Devill, he will haue it of them Mat. 4. 9. for he will haue all the world to worship him, if high and low, rich and poore, bond and free, be all the world, he will compell them to bee subjects or members in his black Regiment Revel. 13. 16. 17.

For these dwell and rule make & change lawes and times in this their habition which is the bottemlesse pit, as the Father Sonne & holy Ghost do in their habitation, which is the New Jerusalem.

The true definition of a true visible Church of Iesus Christ.

1. THat every true visible Church of Christ, are a company of people called and seperated out of the world, (a) By the word of God, Ioyned (b) together in the fellowship of the Gospell by volentary (c) profession of fayth and obedience of Christ (a) Levit. 20. 26. Nehe. 10, 18. Ezeche. 44; 7. 9. 1 Pet. 2. 9. 10. Act, 2. 40. Act, 19. 9. 1 Cor. 1. 12 2 Cor. 6. 17. Revel. 18. 4. (b) Act. 11. 21. 23. Ier. 50. 4, 5 (c) Act. 2. 41.

2 That every true visible Church of Christ, is an independent body of it selfe Revel. 1. 3. chapt. & hath power from Christ her head Coll. 1. 18. 24. to bind & loose; to receive in & cast out by the Keys of the Kingdome Mat. 18. 17. 18. Psa. 149. 8. 9. 1 Cor. 5. 4. 5. 12. 2 Cor. 2. 7. 8.

3 That Jesus Christ hath by his Last wil and Testament given vnto and sett in his Church, sufficient ordinary Officers: with their quallifications Callings and worke, for the Administration of his holy things, and for the sufficient ordinary Instruction, Guidance and service of his Church to the end of the world. Rom. 12. 6. 7. 8. Ephe. 4. 11. 12. 13. Heb. 3. 2. 6. 1 Tim. 3. 2. 8. & Chapt. 5. 9. 10. Act. 6. 3. And that all the Officers in the Church are but onely five and noe more namely Pastor, Teacher, Elder, Deacons,

Widdows. Rom. 12. 7. 8. Ephe. 4. 11. Phil. 1. 1.

1 Tim. 3. 1. & Ch. 5. Tit. 1. 5. 7.

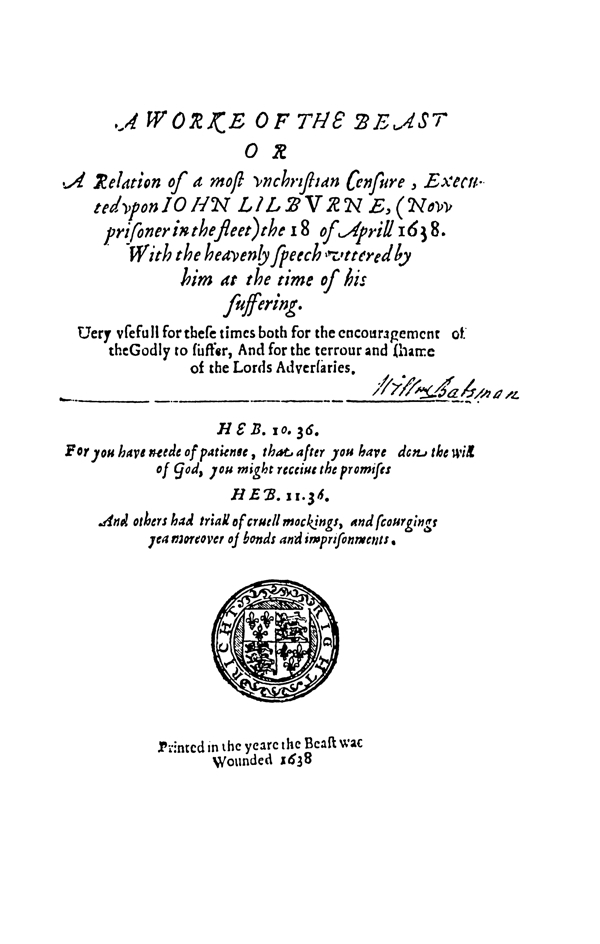

T.3 (1.3.) John Lilburne, A Worke of the Beast (1638).↩

Editing History

- Illegibles corrected: HTML (date)

- Illegibles corrected: XML (date)

- Introduction: date

- Draft online: date

Bibliographical Information

ID NumberT.3 [1638.??] (1.3) John Liburne, A Worke of the Beast (1638).

Full titleJohn Lilburne, A Worke of the Beast, or A Relation of a most unchristian Censure, Executed upon John Lilburne, (Now prisoner in the fleet) the 18 April 1638. With the heavenly speech uttered by him at the time of his suffering. Very usefull for these times both for the encouragement of the Godly to suffer, And for the terrour and shame of the Lords Adversaries.

Heb. 10.36. For you have neede of patience, that after you have done the will of God, you might receive the promises.

Heb. 11.36. And others had triall of cruell mockings, and scourgings yea moreover of bonds and imprisonments.

Printed in the yeare the Beast was Wounded 1638.

Estimated date of publication1638 (no month given).

Thomason Tracts Catalog informationNot listed in TT.

Editor’s Introduction

(Placeholder: Text will be added later.)

Text of Pamphlet

The Publisher to the Reader.

Tender hearted Reader.

OF The wicked it is truely said in Iob. their Light shalbee Put out: Now wee see, in a Candle, beeing almost extinguished, that after it hath glimmered a while, it rayseth some few blazing flashes, and soe suddenly vanisheth.

To speake what I thinke, my minde gives me, that the Lord is now vpon extinguishing the bloody Prelates out of our Land: For whereas they have not, in some late yeares shewed the cruelty which they did before, but now increase in persecution: me thinkes this is a cleere foregoing signe, that (like a snuffe in the socket) their end and ruine is at hand.

I write this, to have thee the more patient, contented, and comforted, when thou either hearest, seest, or readest of their barbarous crueltie; besure their condemnation sleepeth not, but when their wickednes is full, I say when they haue once filled up the measure of their iniquity (the which I trust they haue allmost don) then will the Lord send back’ these locusts to the Bottomlesse pitt, from whence they came.

In the meane time feare not their faces, but stand in the trueth, and let Gods house and his ordinances bee deare to thy soule; And know, that as the Lord gaue strength to this his Servant to suffer joyfully for Christs cause; soe he will to thee and me and all others of his saints,

if he count us worthy to be called thereto.

A WORKE OF THE BEAST, OR A Relation of a most unchristian Censure, executed vpon IOHN LILBVRNE, (Novv prisoner in the fleet) the 18. of Aprill 1638 vvith the heavenly speech vtter by him at the time of his suffering

VPon Wednesday the said 18 of Aprill, Hauing noe certaine notice of the execution of my Censure, till this present morning, I prepared my selfe by prayer unto God, that he would make good his promise, to be vvith me & enable me to undergoe my Affliction vvith joyfullnes & courage: and that he vvould bee a mouth and vtterance vnto mee to enable me to speake that vvhich might make for his greatest honour. And in any meditations my soule did principally pitch vpon these Three places of Scripture.

First, That in Jsay. 41. 10. 11. 12. 13. Feare thou not for I am with thee, be not dismaid for I am thy God, I will strengthen thee, yea I will helpe thee, yea I will uphold thee with the right hand of my righteousnes. Behold all they that were incenced against thee shall be ashamed and confounded, they shall be as nothing, and they that striue with thee shall perrish. Thou shalt seeke them & shall not finde them, even them that contended with thee, they that warr against thee shall be as nothing & as a thing of nought. For I the Lord thy God will hold thee by thy right hand, saying vnto thee, feare not, J will helpe thee, Feare not thou worme Jacob, and yee men of Israell, I will helpe, thus sayth the Lord and thy Redeemer the Holy one of Israell. &c.

Secondly, that place in Isay. 43. 1. 2. Where God speaks thus to his Elect. Feare not for J have Redeemed thee, I have called thee by thy name thou art mine. When thou passest through the waters J wilbe with thee, and though the rivers they shall not over flow thee, when thou walkest through the fire thou shalt not bee burnt, neither shall the flame kindell vpon thee.

Thirdly, that in Heb. 13. 5. 6. In these words For he hath sayd I will never leave thee nor for sake thee, Soe that we may boldly say the Lord is my helper, J will not feare what man can doe to me.

With the consideration of these and other gratious promises, made to his people, I being one of his chosen ones, did claime my share & interest in them, and the Lord of his infinite goodnes enabled me to cast my selfe upon and rest in them, knowing and stedfastly beleeving that he is a God of faithfullnes and power, whoe is able and willing to make good these his promises to the vtmost, and (to his praise be it spoken I desire to speake it) my soule was that morning exceedingly listed up with spiritual consolation: and J felt within me such a divine supportation, that the basenesse of my punishment J was to undergoe did seem as a matter of nothing to me. And I went to my suffering with as willing and joy full a heart as if J had been going to solemnize the day of my maraige with one of the choysest Creatures this world could afford. The Warden of the Fleete hauing sent his men for my old fellow souldler Mr. Iohn Wharton, and my selfe being both in one Chamber, wee made our selues readie to goe to the place of execution. I tooke the old man by the hand and led him downe three payre of stayers, and soe along the yard till we came to the Gate. And when we came there George Harrington the Porter told me J must stay alitle, and after our parting (commending one another to the protection of our alsufficient God) I was bid goe to the Porters Lodge, noe sooner was I gone in, but came Iohn Hawes, the other Porter to me vsing these words.

Mr. Lilburne, I am very sorie for your punishment, you are now to undergoe, you must stripp you, and be whipt from hence to Westminster.

I replied, the will of my God be done, for I knowe he will carry me through it with an vndaunted Spirit; But I must confesse it seemed at the first a little strange to me, in regard I had no more notice given me for my preperation for soe sore a punishment. For I thought I should not haue been whipt through the streete but onely at the Pillory: And soe passing a long the Lane being attended with many Staves and Halberts, as Christ was when he was apprehended by his Enimies and led to the High Priests Hall. Mat.-26, we came to Fleete-bridge where was a Cart standing ready for me. And I being commanded to stripp me, I did it with all willingnes and cheerefullnes, where upon the executioner tooke out a Corde and tyed my hands to the Carts Arsse, which caused me to vtter these words, Wellcome be the Crosse of Christ,

With that there drew neere a Yong man of my acquentance, and bid me put on a Couragious resolution to suffer cheerfully & not to dishonor my cause for you suffer (said he) for a good cause, I gaue him thanks, for his christian incouragement, J replying I know the cause is good, for it is Gods cause, & for my own part I am cheerful & merry in the Lord, & am as well contented with this my present portion as if I were to receiue my present liberty. For I knowe my God that hath gone along with me hither to, will carry me though to the end. And for the affliction itself, though it be the punishment inflicted upon Rogues. yet I esteeme it not the least disgrace, but the greatest honour that can be done unto me, that the Lord counts me worthy to suffer any thing for his great name;

And you my Brethren that doe now here behold my present condition this day, be not discouraged, be not discouraged at the waies of Godlinesse by reason of the Crosse which accompanies it, for it is the lot and portion of all which will lius Godly in Christ, Iesus to suffer persecution,

The Cart being readie to goe forward. I spake to the executioner (when I saw him pull out his Corded whipp out of his pocket) after this manner, Well my friend doe thy office. To which he replyed I haue whipt many a Rogue but now I shall whip an honest man. but be not discouraged (said he) it will be soon over.

To which I replyed, J knowe my God hath not onely enabled me to beleeve in his name, but alsoe to suffer for his sake, Soe the Carman drove forward his Cart, and I laboured with my God for strength to submit my back with cheerfullnes unto the smiter. And he heard my desire & granted my request, for when the first stripe was giuen I felt not the leaft paine but said; Blessed be thy name O Lord my God that hast counted mee worthy to suffer for thy glorious names sake; And at the giving of the second, I cried out with a loud voice Hallelujah, Hallelujah, Glory, Honour, and Praise, bee given to thee O Lord forever, and to the Lambe that sitts vpon the Throne. Soe wee vvent vp Fleetstreete, the Lord enabling me to endure the stripes vvith luch patience and cherefullnes, that J did not in the least manner shevv the least discontent at them; for my God hardened my backe, and steeled my reynes, and tooke a vvay the smart and payne of the stripes from mee.

But J must confesse, if I had had no more but my owne naturall strength, I had suncke vnder the burden of my punishement; for to the flesh the paine was uery grevious & heavy: But my God in whom I did trust was higher and stronger then my selfe, whoe strengthened and enabled mee not onely to undergoe the punishment with cherefullnes: but made me Triumph & with a holy disdaine to insult over my torments.

And as we went along the Strand, many friends spoke to me & asked how I did, & bid me be cherfull, to whom I replied, I was merry and cheerfull: and was upheld with a diuine and heauenly supportation, comforted with the sweet consolations of Gods spirit. And about the middle of the Strand, there came a Friend and bid me speake with boldnesse. To whom I replied, when the time comes soe I will. for then if I should haue spoken and spent my strength, it would haue been but as water spilt on the ground, in regard of the noyse and presse of people. And alsoe at that time I was not in a fitt temper to speake: because the dust much troubled mee, and the Sunne shined very hot vpon mee. And the Tipstaffe man at the first vvould not let mee haue my hatt to keepe the vehement heate of the Sunne from my head: Alsoe hee many times spake to the Cart man to driue softly, Soe that the heate of the Sunne exceedingly peirced my head: and made me somwhat faint. But yet my God vpheld me vvith courage, and made me vndergoe it vvith a joyfull heart. And vvhen J came to Chearing Crosse some Christian friends spake to me and bid me be of good cheere.

Soe I am (said I) for I rest not in my ovvne strength. but J fight vnder the Banner of my great and mightie Captaine the Lord Jesus Christ who hath conquered all his Enemies, and I doubt not but through his strength I shall conquer and over come all my sufferings, for his power upholdes mee, his strength enables mee, his presence cheeres mee, and his Spirit comforts mee, and I looke for an immortall Crowne which never shall fade nor decay, the assured hope and expectation where of makes, mee to contemne my sufferings, and count them as nothing, ffor my momentany affliction will worke for me a farre more exceeding Crowne and weight of glory. And as I went by the Kings pallace a great Multitude of people came to looke vpon me. And passing through the gate vnto Westminster, Many demanded what was the matter.

To whom I replied, my Brethren, against the Law of God, against the law of the Land, against the King or State haue J not committed the least offence that deserves this punishment, but only J suffer as an object of the Prelates cruelty and malice; and hereupon, one of the Warden of the Fleets-officers, beganne to interrupt me, and tells mee my suffering was just and therefore I should hold my tongue; Whom J bidd meddle with his owne businesse, for I would speake come what would, for my cause was good for which I suffered, and here I was ready to sheb my dearest blood for it.

And as we went through Kings Street many encouraged me, and bidd me be cheerefull; O thers whose faces (to my knowledge) I never sawe before; and who J verilie thinke knew not the cause of my suffering, but seeing my cheerefullnes vnder it, beseeched the Lord to blesse me and strenthen mee.

At the last wee came to the Pillary, where I was unloosed from the Cart, and having put one some of my cloathes wee went to the Taverne, vvhere J staid a prittie vvhile vvaiting for my Surgeon.

vvhoe vvas not yet come to dresse mee. Where vvere many of my Friends, whoe exceedingly rejoyced to see my courage. that the Lord had enabled me to vndergoe my punishment soe willingly.

Whoe asked me how I did. I tould them, as well as ever I was in my life I blesse my God for it. for I felt such inward joy and comfort, chearing vp my soule, that I lightly esteemed my sufferings.

And this I counted my weding day in which I was married to the Lord Iesus Christ: for now I knowe he loues me in that he hath bestowed soe rich apparrell this day upon me, and counted me worthie to suffer for his sake. I hauing a desire to retire into a private roome from the multitude of people that were about me, which made me like to faint: I had not been ther long but Mr. Lightburne the Tipstaffe of the Star-Chamber, came to me saying the Lords sent him to me, to knowe if I would acknowledge my selfe to be in a fault and then be knew what to say unto me. To whom I replied, Haue their Honours caused me to be whipt from the Fleet to Westminster; and doe they now send to knowe if I wil acknowledge a fault. They should have done this before I had beene whipt; for now seeing I have vndergone the greatest part of my punishment, I hope the Lord will assist me to goe through it all, and besides, if I would haue done this at the first I needed not to haue come to this, But as I tould the Lords when J was before them at the Barre. Soe I desire you to tell them againe, that I am not conscious to my selfe of doing any thing that deserues a submission, but yet I doe willingly submit to their Lordships pleasures in my Censure. He told me if I would confesse, a fault it would saue me astanding on the Pillary otherwise I must undergoe the burden of it.

Wel, (Said I) J regard not alittle out ward disgrace for the cause of my God, I haue found alreadie that sweetnesse in him in whom I haue beleeued, that through his strength I am able to undergoe any thing that shalbee inflicted on me; But me thinks that J had verie hard measure that I should be condemned and thus punished vpon two Oaths, in which the party hath most falslie soresworne himselfe: and because I would not take an Oath to betray mine owne innocency; Why Paul found more favour and mercy from the Heathen Roman-Governors, for they would not put him to an Oath to accuse himselfe, but suffered him to make the best defence he could for himselfe, neither would they condemne him before his accusers and he were brought face to face, to justifie and fully to proue their accusation: But the Lords haue not dealt so with me, for my accusers and I were neuer brought face to face to justifie their accusation against me: it is true two false Oathes were Sworne against mee: and I was therevpon condemned. and because I would not accuse my selfe. It is true (said hee) it was soe with Paul but the Lawes of this Land, are otherwise then their Lawes were in those dayes. Then said I, they are vvorse and more cruell, then the Lawes of the Pagans and Heathen Romans were. whoe would condemne no man without wittnesses and they should be brought face to face; to justifie their accusation. And so hee went away, & I prepared my selfe for the Pillary, to which J went with a joyfull courage. and when I was vpon it, I made obeysance to the Lords, some of them as (J suppose) looking out at the Starr-Chamber-window, towards mee. And so I putt my neck into the hole, which beeing a great deale to low for me, it was very painfull to me in regard of the continuance of time that I stood on the Pillary: which was a bout two houres, my back also being very sore, and the Sunne shining exceeding hot. And the Tipstaffe man, not suffering mee to keepe on my hat, to defend my head from the heat of the Sunne. So that I stood there in great paine. Yet through the strength of my God I vndorwent it with courage: to the very last minute. And lifting vp my heart and spirit vnto my God,

While I was thus standing on the Pillary. J craued his Powerfull assistance: with the spirit of wisdome and courage, that I might open my mouth with boldnesse: and speake those things that might make for his greatest glory, and the good of his people, and soe casting my eyes on the multitude, I beganne to speake after this manner.

My Christean Brethren, to all you that loue the Lord Iesus Christ. and desire that hee should raigne and rule in your hearts and liues, to you especially: and to as many as heare me this day: I direct my speech.

J stand here in the place of ignominy and shame. Yet to mee it is not so, but I owne and imbrace it, as the Wellcome Crosse of Christ. And as a badge of my Christian Profession. I haue been already whipt from the Fleet to this place, by vertue of a Censure: from the Honourable Lords of the Starr Chamber hereunto, The Cause of my Censure I shall declare unto you as briefly as I canne.

The Lord by his speciall hand of providence so ordered it, that Not long agoe I was in Holland. Where I was like to haue settled my selfe in a Course of trading, that might haue brought me in a pretty large portion of earthlie things; (after which my heart did too much runne) but the Lord hauing a better portion in store for mee, and more durable riches to bestow vpon my soule. By the same hand of providence: brought me back a gaine. And cast me into easie affliction, that there by I might be weaned from the world, and see the vanitie and emptines of all things therein. And he hath now pitched my soule vpon such an object of beautie, amiablenessc: & excelencie, as is as permanent and endurable as eternitie it selfe, Namely the personall excelencie of the Lord Iesus Christ, the sweetnesse of whose presence, no affliction can ever be able to wrest out of my soule.

Now while J was in Holland, it seemes ther were divers Bookes, of that Noble and Renowned Dr. Iohn Bastwicks sent into England, which came to the hands of one Edmond Chillington, for the sending over which I was taken, and apprehended, the plot being before laid, by one Iohn Chilliburne (whom I supposed) & tooke to be my friend) servant to my old fellow souldier Mr. John Wharton living in Bow-lane (after this manner.)

I walking in the Street, with the said Iohn Chilliburne, was taken by the Pursevant and his men, the said Iohn as I verily beleeve, hauing given direction to them: where to stand, and he himselfe was the third man that laid hands on me to hold mee.

Now at my Censure before the Lords: I there declared vpon the word of a Christian that I sent not over those Bookes, neither did I know the Shipp that brought them, nor any of the men that belonged to the Shipp, nor to my knowledge did I ever see, either Shipp: or any appertaining to it, in all my dayes.

Besides this, I was accused at my examination before, the Kings Atturny at his Chamber, by the said Edmond Chillington Button Seller Iiving in Canon street neere Abchurch Lane, and late Prisoner in Bridewell & Newgate, for printing 10. or 12. thousand Bookes in Holland, and that J would haue printed the Vnmasking the mistery of iniquitie if I could haue gott a true Copie of it, and that I had a Chamber in Mr. John Foots house at Delfe where hee thinkes the bookes were kept. Now here I declare before you all, vpon the word of a suffering Christian: that hee might haue as well accused mee of printing a hundred thousand bookes, and the on been as true as the other; And for the printing the Vnmasking the Mistery of Iniquity, vpon the word of an honest man I never saw, nor to my knowledge heard of the Booke, till I came back againe into England: And for my having a Chamber in Mr. John Foots house at Delfe, where he thinkes the Bookes were kept. J was soe farre from having a Chamber there, as I never lay in his house, but twice or thrice at the most, and upon the last Friday of the last Tearme I was brought to the Star-Chamber Barre, where before mee was read the said Edmond Chillingtons Affidavit, vpon Oath, against Mr. John Wharton and my selfe. The Summe of which Oath was, That hee and I had Printed (at Rotterdam in Holland,) Dr. Bastwicks Answer, and his Letany, with divers other scandalous Bookes.

Now here againe I speake it in the presence of God, & all you that heare mee, that Mr. Wharton, and I never joyned together in printing, either these or any other Bookes whatsoever. Neither did I receive any mony from him, toward the printing any.

Withall, in his first Oath, hee peremtorilie swore that wee had printed them at Rotterdam. Vnto which I likewise say, That hee hath in this particular forsworne himselfe, for my owne part, I never in all my daies either printed, or caused to be printed, either for my selfe or Mr. Wharton any Bookes at Rotterdam. Neither did I come into any Printing house there all the time I was in the Citty.

And then vpon the Twesday after he swore, against both of us againe. The summe of which Oaths was, that I had confessed to him (which is most false) that I had Printed Dr. Bastwicks Answer to Sr. John Banks his Information, and his Letany; & another Booke called Certaine answers to certaine Objections; And another Booke called The vanity & impiety of the old Letany; & that J had divers other Bookes of the said Dr. Bastwicks in Printing, & that Mr. Wharton, had beene at the charges of Printing a Booke called A Breviae of the Bishops late proceeding; and another Booke called 16. new Queries, and in this his Oath hath sworne they were Printed at Rotterdam, or some where else in Holland; & that on James Oldam, a Turner keping Shop at Westminster hall-gate disperced divers of these bookes. Now in this Oath he hath againe forsworne himselfe in a high degree, for wheras he took his Oath that I had printed the Booke called The Vanitie and impiety of the old Letany, I here speake it before you all, that I never in all my daies did see one of them in print, but I must confess, I haue seen & read it, in written hand, before the Dr. was censured, & as for other books, of which he saith I haue diverse in printing. To that I answer, that for mine owne perticuler I never read nor saw any of the Drs. Bookes: but the forenamed foure in English, and one little thing more of about; two sheetes of paper, which is annexed to the Vanity of the Old Letany, And as for his Lattine Bookes J never saw any but two: Namely his Flagellam, for which he was first censured in the High-Commission Court: and his Apologeticus, which were both in print long before J knew the Dr. But it is true, there is a second edition of his Flagellam, but that was at the presse aboue two yeares agoe: namly Anno 1634. And some of this impression was in England before J came out of Holland,

And these are the maine things for which I was Censured and Condemned. Being two Oaths in which the said Chillington, hath palpably forsworne himselfe. And if hee had not forsworne himselfe. Yet by the law (as I am given to vnderstand) I might have excepted against him, being a guilty person himselfe and a Prisoner, and did that which hee did against thee for pvrchasing his owne liberty which hee hath by such Iudasly meanes gott and obtained. Who is also knowne to bee a lying fellow, as J told the Lords I was able to proue and make good.

But besides all this, there was an inquisition Oath tendered vnto mee (which J refused to take) on foure severall daies; the summe of which Oath is thus much. You shall sweare that you shall make true answer to all things that shall be asked of you: So helpe you God. Now this Oath I refused as a sinfull and vnlawfull Oath: it being the High-Commission Oath, with which the Prelates euer haue and still do so butcherly torment, afflict and vndoe, the deare Saints and Servants of God, It is also an Oath against the Law of the Land, As Mr. Nicholas Fuller in his Argument doth proue, And also it is expressly against the Petition of Right an Act of Parlament Enacted in the second yeare of our King. Againe, it is absolutely against the Law of God, for that law requires noe man to accuse himselfe, but if any thing be laid to his charge: there must come two or three witnesses at the least to proue it. It is also against the practise of Christ himselfe, who in all his examinations before the High Priest would not accuse himselfe: but vpon their demands, returned this answer: Why aske jea mee, go to them that heard mee.

With all this Oath is against the uery law of nature, for nature is alwaies a preserver of it selfe and not a distroyer. But if a man takes this wicked Oath he distroyes and vndoes himselfe, as daily experience doth witnesse. Nay it is worse then the Law of the Heathen Romans, as we may reade Act. 25. 16. For when Paull stood before the Pagan Governours, and the Iews required Judgement against him, the Governour replyed, it is not the manner of the Romans to condemne any man before his accusers & hee were brought face to face to justify their accusation. But for my owne part, if I had beene proceeded against by a Bill, J would haue answered & justified all that they coulde have proved against me, & by the strength of my God would have sealed whatsoever I have don with my bloud, for I am privy to mine own actions, & my conscience beares me witnes that I have laboured ever since the Lord in mercy made the riches of his grace known to my Soule, to keep a good conscience and to walke inoffensably both towards God, & man. But as for that Oath that was put unto me I did refuse to take it, as a sinfull and unlawfull Oath, & by the strength of my God enabling me I wil never take it though I be puld in peices with wilde horses as the ancient Chritians were by the bloudy Tirants, in the Primitive Church; neither shall I thinke that man a faithfull Subject, of Christs Kingdome, that shall at any time hereafter take it, seeing the wickednes of it hath been so apparently laid open by so many, for the refusall wherof many doe suffer cruell persecution to this day. Thus have J as briefly as I could; declared unto you, the whole cause of my standing here this day, I being upon these grounds censured by the Lords at the Starr-chamber on the last Court day of the last tearme to pay 500. põ. to the King and to receive the punishment which with rejoicing I hane undergon, vnto whose censure I do with willingnes & cheeresulnes submit, my selfe.