Kalidasa: Life and Works

Source: Introduction to Translations of Shakuntala and Other Works, by Arthur W. Ryder (London: J.M. Dent, 1920).

INTRODUCTION . KALIDASA—HIS LIFE AND WRITINGS

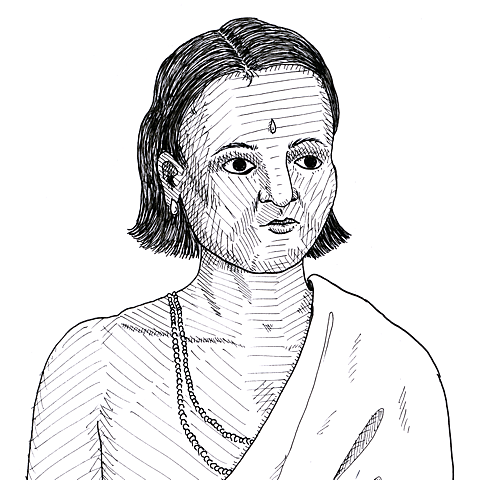

Kalidasa probably lived in the fifth century of the Christian era. This date, approximate as it is, must yet be given with considerable hesitation, and is by no means certain. No truly biographical data are preserved about the author, who nevertheless enjoyed a great popularity during his life, and whom the Hindus have ever regarded as the greatest of Sanskrit poets. We are thus confronted with one of the remarkable problems of literary history. For our ignorance is not due to neglect of Kalidasa’s writings on the part of his countrymen, but to their strange blindness in regard to the interest and importance of historic fact. No European nation can compare with India in critical devotion to its own literature. During a period to be reckoned not by centuries but by millenniums, there has been in India an unbroken line of savants unselfishly dedicated to the perpetuation and exegesis of the native masterpieces. Editions, recensions, commentaries abound; poets have sought the exact phrase of appreciation for their predecessors: yet when we seek to reconstruct the life of their greatest poet, we have no materials except certain tantalising legends, and such data as we can gather from the writings of a man who hardly mentions himself.

One of these legends deserves to be recounted for its intrinsic interest, although it contains, so far as we can see, no grain of historic truth, and although it places Kalidasa in Benares, five hundred miles distant from the only city in which we certainly know that he spent a part of his life. According to this account, Kalidasa was a Brahman’s child. At the age of six months he was left an orphan and was adopted by an ox-driver. He grew to manhood without formal education, yet with remarkable beauty and grace of manner. Now it happened that the Princess of Benares was a blue-stocking, who rejected one suitor after another, among them her father’s counsellor, because they failed to reach her standard as scholars and poets. The rejected counsellor planned a cruel revenge. He took the handsome ox-driver from the street, gave him the garments of a savant and a retinue of learned doctors, then introduced him to the princess, after warning him that he was under no circumstances to open his lips. The princess was struck with his beauty and smitten to the depths of her pedantic soul by his obstinate silence, which seemed to her, as indeed it was, an evidence of profound wisdom. She desired to marry Kalidasa, and together they went to the temple. But no sooner was the ceremony performed than Kalidasa perceived an image of a bull. His early training was too much for him; the secret came out, and the bride was furious. But she relented in response to Kalidasa’s entreaties, and advised him to pray for learning and poetry to the goddess Kali. The prayer was granted; education and poetical power descended miraculously to dwell with the young ox-driver, who in gratitude assumed the name Kalidasa, servant of Kali. Feeling that he owed this happy change in his very nature to his princess, he swore that he would ever treat her as his teacher, with profound respect but without familiarity. This was more than the lady had bargained for; her anger burst forth anew, and she cursed Kalidasa to meet his death at the hands of a woman. At a later date, the story continues, this curse was fulfilled. A certain king had written a half-stanza of verse, and had offered a large reward to any poet who could worthily complete it. Kalidasa completed the stanza without difficulty; but a woman whom he loved discovered his lines, and greedy of the reward herself, killed him.

Another legend represents Kalidasa as engaging in a pilgrimage to a shrine of Vishnu in Southern India, in company with two other famous writers, Bhavabhuti and Dandin. Yet another pictures Bhavabhuti as a contemporary of Kalidasa, and jealous of the less austere poet’s reputation. These stories must be untrue, for it is certain that the three authors were not contemporary, yet they show a true instinct in the belief that genius seeks genius, and is rarely isolated.

This instinctive belief has been at work with the stories which connect Kalidasa with King Vikramaditya and the literary figures of his court. It has doubtless enlarged, perhaps partly falsified the facts; yet we cannot doubt that there is truth in this tradition, late though it be, and impossible though it may ever be to separate the actual from the fanciful. Here then we are on firmer ground.

King Vikramaditya ruled in the city of Ujjain, in West-central India. He was mighty both in war and in peace, winning especial glory by a decisive victory over the barbarians who pressed into India through the northern passes. Though it has not proved possible to identify this monarch with any of the known rulers, there can be no doubt that he existed and had the character attributed to him. The name Vikramaditya—Sun of Valour—is probably not a proper name, but a title like Pharaoh or Tsar. No doubt Kalidasa intended to pay a tribute to his patron, the Sun of Valour, in the very title of his play, Urvashi won by Valour.

King Vikramaditya was a great patron of learning and of poetry. Ujjain during his reign was the most brilliant capital in the world, nor has it to this day lost all the lustre shed upon it by that splendid court. Among the eminent men gathered there, nine were particularly distinguished, and these nine are known as the “nine gems.” Some of the nine gems were poets, others represented science—astronomy, medicine, lexicography. It is quite true that the details of this late tradition concerning the nine gems are open to suspicion, yet the central fact is not doubtful: that there was at this time and place a great quickening of the human mind, an artistic impulse creating works that cannot perish. Ujjain in the days of Vikramaditya stands worthily beside Athens, Rome, Florence, and London in their great centuries. Here is the substantial fact behind Max Müller’s often ridiculed theory of the renaissance of Sanskrit literature. It is quite false to suppose, as some appear to do, that this theory has been invalidated by the discovery of certain literary products which antedate Kalidasa. It might even be said that those rare and happy centuries that see a man as great as Homer or Vergil or Kalidasa or Shakespeare partake in that one man of a renaissance.

It is interesting to observe that the centuries of intellectual darkness in Europe have sometimes coincided with centuries of light in India. The Vedas were composed for the most part before Homer; Kalidasa and his contemporaries lived while Rome was tottering under barbarian assault.

To the scanty and uncertain data of late traditions may be added some information about Kalidasa’s life gathered from his own writings. He mentions his own name only in the prologues to his three plays, and here with a modesty that is charming indeed, yet tantalising. One wishes for a portion of the communicativeness that characterises some of the Indian poets. He speaks in the first person only once, in the verses introductory to his epic poem The Dynasty of Raghu.1 Here also we feel his modesty, and here once more we are balked of details as to his life.

We know from Kalidasa’s writings that he spent at least a part of his life in the city of Ujjain. He refers to Ujjain more than once, and in a manner hardly possible to one who did not know and love the city. Especially in his poem The Cloud-Messenger does he dwell upon the city’s charms, and even bids the cloud make a détour in his long journey lest he should miss making its acquaintance.2

We learn further that Kalidasa travelled widely in India. The fourth canto of The Dynasty of Raghu describes a tour about the whole of India and even into regions which are beyond the borders of a narrowly measured India. It is hard to believe that Kalidasa had not himself made such a “grand tour”; so much of truth there may be in the tradition which sends him on a pilgrimage to Southern India. The thirteenth canto of the same epic and The Cloud-Messenger also describe long journeys over India, for the most part through regions far from Ujjain. It is the mountains which impress him most deeply. His works are full of the Himalayas. Apart from his earliest drama and the slight poem called The Seasons, there is not one of them which is not fairly redolent of mountains. One, The Birth of the War-god, might be said to be all mountains. Nor was it only Himalayan grandeur and sublimity which attracted him; for, as a Hindu critic has acutely observed, he is the only Sanskrit poet who has described a certain flower that grows in Kashmir. The sea interested him less. To him, as to most Hindus, the ocean was a beautiful, terrible barrier, not a highway to adventure. The “sea-belted earth” of which Kalidasa speaks means to him the mainland of India.

Another conclusion that may be certainly drawn from Kalidasa’s writing is this, that he was a man of sound and rather extensive education. He was not indeed a prodigy of learning, like Bhavabhuti in his own country or Milton in England, yet no man could write as he did without hard and intelligent study. To begin with, he had a minutely accurate knowledge of the Sanskrit language, at a time when Sanskrit was to some extent an artificial tongue. Somewhat too much stress is often laid upon this point, as if the writers of the classical period in India were composing in a foreign language. Every writer, especially every poet, composing in any language, writes in what may be called a strange idiom; that is, he does not write as he talks. Yet it is true that the gap between written language and vernacular was wider in Kalidasa’s day than it has often been. The Hindus themselves regard twelve years’ study as requisite for the mastery of the “chief of all sciences, the science of grammar.” That Kalidasa had mastered this science his works bear abundant witness.

He likewise mastered the works on rhetoric and dramatic theory—subjects which Hindu savants have treated with great, if sometimes hair-splitting, ingenuity. The profound and subtle systems of philosophy were also possessed by Kalidasa, and he had some knowledge of astronomy and law.

But it was not only in written books that Kalidasa was deeply read. Rarely has a man walked our earth who observed the phenomena of living nature as accurately as he, though his accuracy was of course that of the poet, not that of the scientist. Much is lost to us who grow up among other animals and plants; yet we can appreciate his “bec-black hair,” his ashoka-tree that “sheds his blossoms in a rain of tears,” his river wearing a sombre veil of mist:

- Although her reeds seem hands that clutch the dress

- To hide her charms;

his picture of the day-blooming water-lily at sunset:

- The water-lily closes, but

- With wonderful reluctancy;

- As if it troubled her to shut

- Her door of welcome to the bee.

The religion of any great poet is always a matter of interest, especially the religion of a Hindu poet; for the Hindus have ever been a deeply and creatively religious people. So far as we can judge. Kalidasa moved among the jarring sects with sympathy for all, fanaticism for none. The dedicatory prayers that introduce his dramas are addressed to Shiva. This is hardly more than a convention, for Shiva is the patron of literature. If one of his epics, The Birth of the War-god, is distinctively Shivaistic, the other, The Dynasty of Raghu, is no less Vishnuite in tendency. If the hymn to Vishnu in The Dynasty of Raghu is an expression of Vedantic monism, the hymn to Brahma in The Birth of the War-god gives equally clear expression to the rival dualism of the Sankhya system. Nor are the Yoga doctrine and Buddhism left without sympathetic mention. We are therefore justified in concluding that Kalidasa was, in matters of religion, what William James would call “healthy-minded,” emphatically not a “sick soul.”

There are certain other impressions of Kalidasa’s life and personality which gradually become convictions in the mind of one who reads and re-reads his poetry, though they are less easily susceptible of exact proof. One feels certain that he was physically handsome, and the handsome Hindu is a wonderfully fine type of manhood. One knows that he possessed a fascination for women, as they in turn fascinated him. One knows that children loved him. One becomes convinced that he never suffered any morbid, soul-shaking experience such as besetting religious doubt brings with it, or the pangs of despised love; that on the contrary he moved among men and women with a serene and godlike tread, neither self-indulgent nor ascetic, with mind and senses ever alert to every form of beauty. We know that his poetry was popular while he lived, and we cannot doubt that his personality was equally attractive, though it is probable that no contemporary knew the full measure of his greatness. For his nature was one of singular balance, equally at home in a splendid court and on a lonely mountain, with men of high and of low degree. Such men are never fully appreciated during life. They continue to grow after they are dead.

II

Kalidasa left seven works which have come down to us: three dramas, two epics, one elegiac poem, and one descriptive poem. Many other works, including even an astronomical treatise, have been attributed to him; they are certainly not his. Perhaps there was more than one author who bore the name Kalidasa: perhaps certain later writers were more concerned for their work than for personal fame. On the other hand, there is no reason to doubt that the seven recognised works are in truth from Kalidasa’s hand. The only one concerning which there is reasonable room for suspicion is the short poem descriptive of the seasons, and this is fortunately the least important of the seven. Nor is there evidence to show that any considerable poem has been lost, unless it be true that the concluding cantos of one of the epics have perished. We are thus in a fortunate position in reading Kalidasa: we have substantially all that he wrote, and run no risk of ascribing to him any considerable work from another hand.

Of these seven works, four are poetry throughout; the three dramas, like all Sanskrit dramas, are written in prose, with a generous mingling of lyric and descriptive stanzas. The poetry, even in the epics, is stanzaic; no part of it can fairly be compared to English blank verse. Classical Sanskrit verse, so far as structure is concerned, has much in common with familiar Greek and Latin forms: it makes no systematic use of rhyme; it depends for its rhythm not upon accent, but upon quantity. The natural medium of translation into English seems to me to be the rhymed stanza;1 in the present work the rhymed stanza has been used, with a consistency perhaps too rigid, wherever the original is in verse.

Kalidasa’s three dramas bear the names: Malavika and Agnimitra, Urvashi, and Shakuntala. The two epics are The Dynasty of Raghu and The Birth of the War-god. The elegiac poem is called The Cloud-Messenger, and the descriptive poem is entitled The Seasons. It may be well to state briefly the more salient features of the Sanskrit genres to which these works belong.

The drama proved in India, as in other countries, a congenial form to many of the most eminent poets. The Indian drama has a marked individuality, but stands nearer to the modern European theatre than to that of ancient Greece; for the plays, with a very few exceptions, have no religious significance, and deal with love between man and woman. Although tragic elements may be present, a tragic ending is forbidden. Indeed, nothing regarded as disagreeable, such as fighting or even kissing, is permitted on the stage; here Europe may perhaps learn a lesson in taste. Stage properties were few and simple, while particular care was lavished on the music. The female parts were played by women. The plays very rarely have long monologues, even the inevitable prologue being divided between two speakers, but a Hindu audience was tolerant of lyrical digression.

It may be said, though the statement needs qualification in both directions, that the Indian dramas have less action and less individuality in the characters, but more poetical charm than the dramas of modern Europe.

On the whole, Kalidasa was remarkably faithful to the ingenious but somewhat over-elaborate conventions of Indian dramaturgy. His first play, the Malavika and Agnimitra, is entirely conventional in plot. The Shakuntala is transfigured by the character of the heroine. The Urvashi, in spite of detail beauty, marks a distinct decline.

The Dynasty of Raghu and The Birth of the War-god belong to a species of composition which it is not easy to name accurately. The Hindu name kavya has been rendered by artificial epic, épopée savante, Kunstgedicht. It is best perhaps to use the term epic, and to qualify the term by explanation.

The kavyas differ widely from the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, epics which resemble the Iliad and Odyssey less in outward form than in their character as truly national poems. The kavya is a narrative poem written in a sophisticated age by a learned poet, who possesses all the resources of an elaborate rhetoric and metric. The subject is drawn from time-honoured mythology. The poem is divided into cantos, written not in blank verse but in stanzas. Several stanza-forms are commonly employed in the same poem, though not in the same canto, except that the concluding verses of a canto are not infrequently written in a metre of more compass than the remainder.

I have called The Cloud-Messenger an elegiac poem, though it would not perhaps meet the test of a rigid definition. The Hindus class it with The Dynasty of Raghu and The Birth of the War-god as a kavya, but this classification simply evidences their embarrassment. In fact, Kalidasa created in The Cloud-Messenger a new genre. No further explanation is needed here, as the entire poem is translated below.

The short descriptive poem called The Seasons has abundant analogues in other literatures, and requires no comment.

It is not possible to fix the chronology of Kalidasa’s writings, yet we are not wholly in the dark. Malavika and Agnimitra was certainly his first drama, almost certainly his first work. It is a reasonable conjecture, though nothing more, that Urvashi was written late, when the poet’s powers were waning. The introductory stanzas of The Dynasty of Raghu suggest that this epic was written before The Birth of the War-god, though the inference is far from certain. Again, it is reasonable to assume that the great works on which Kalidasa’s fame chiefly rests—Shakuntala, The Cloud-Messenger, The Dynasty of Raghu, the first eight cantos of The Birth of the War-god—were composed when he was in the prime of manhood. But as to the succession of these four works we can do little but guess.

Kalidasa’s glory depends primarily upon the quality of his work, yet would be much diminished if he had failed in bulk and variety. In India, more than would be the case in Europe, the extent of his writing is an indication of originality and power; for the poets of the classical period underwent an education that encouraged an exaggerated fastidiousness, and they wrote for a public meticulously critical. Thus the great Bhavabhuti spent his life in constructing three dramas; mighty spirit though he was, he yet suffers from the very scrupulosity of his labour. In this matter, as in others, Kalidasa preserves his intellectual balance and his spiritual initiative: what greatness of soul is required for this, every one knows who has ever had the misfortune to differ in opinion from an intellectual clique.

III

Le nom de Kâlidâsa domine la poésie indienne et la résume brillamment. Le drame, l’épopée savante, l’élégie attestent aujourd’hui encore la puissance et la souplesse de ce magnifique génie; seul entre les disciples de Sarasvatî [the goddess of eloquence], il a eu le bonheur de produire un chef-d’œuvre vraiment classique, où l’Inde s’admire et où l’humanité se reconnaît. Les applaudissements qui saluèrent la naissance de Çakuntalá à Ujjayinî ont après de longs siècles éclaté d’un bout du monde à l’autre, quand William Jones l’eut révélée à l’Occident. Kâlidâsa a marqué sa place dans cette pléiade étincelante où chaque nom résume une période de l’esprit humain. La série de ces noms forme l’histoire, ou plutôt elle est l’histoire même.1

It is hardly possible to say anything true about Kalidasa’s achievement which is not already contained in this appreciation. Yet one loves to expand the praise, even though realising that the critic is by his very nature a fool. Here there shall at any rate be none of that cold-blooded criticism which imagines itself set above a world-author to appraise and judge, but a generous tribute of affectionate admiration.

The best proof of a poet’s greatness is the inability of men to live without him; in other words, his power to win and hold through centuries the love and admiration of his own people, especially when that people has shown itself capable of high intellectual and spiritual achievement.

For something like fifteen hundred years, Kalidasa has been more widely read in India than any other author who wrote in Sanskrit. There have also been many attempts to express in words the secret of his abiding power: such attempts can never be wholly successful, yet they are not without considerable interest. Thus Bana, a celebrated novelist of the seventh century, has the following lines in some stanzas of poetical criticism which he prefixes to a historical romance:

- Where find a soul that does not thrill

- In Kalidasa’s verse to meet

- The smooth, inevitable lines

- Like blossom-clusters, honey-sweet?

A later writer, speaking of Kalidasa and another poet, is more laconic in this alliterative line: Bhaso hasah, Kalidaso vilasah—Bhasa is mirth, Kalidasa is grace.

These two critics see Kalidasa’s grace, his sweetness, his delicate taste, without doing justice to the massive quality without which his poetry could not have survived.

Though Kalidasa has not been as widely appreciated in Europe as he deserves, he is the only Sanskrit poet who can properly be said to have been appreciated at all. Here he must struggle with the truly Himalayan barrier of language. Since there will never be many Europeans, even among the cultivated, who will find it possible to study the intricate Sanskrit language, there remains only one means of presentation. None knows the cruel inadequacy of poetical translation like the translator. He understands better than others can, the significance of the position which Kalidasa has won in Europe. When Sir William Jones first translated the Shakuntala in 1789, his work was enthusiastically received in Europe, and most warmly, as was fitting, by the greatest living poet of Europe. Since that day, as is testified by new translations and by reprints of the old, there have been many thousands who have read at least one of Kalidasa’s works; other thousands have seen it on the stage in Europe and America.

How explain a reputation that maintains itself indefinitely and that conquers a new continent after a lapse of thirteen hundred years? None can explain it, yet certain contributory causes can be named.

No other poet in any land has sung of happy love between man and woman as Kalidasa sang. Every one of his works is a love-poem, however much more it may be. Yet the theme is so infinitely varied that the reader never wearies. If one were to doubt from a study of European literature, comparing the ancient classics with modern works, whether romantic love be the expression of a natural instinct, be not rather a morbid survival of decaying chivalry, he has only to turn to India’s independently growing literature to find the question settled. Kalidasa’s love-poetry rings as true in our ears as it did in his countrymen’s ears fifteen hundred years ago.

It is of love eventually happy, though often struggling for a time against external obstacles, that Kalidasa writes. There is nowhere in his works a trace of that not quite healthy feeling that sometimes assumes the name “modern love.” If it were not so, his poetry could hardly have survived; for happy love, blessed with children, is surely the more fundamental thing. In his drama Urvashi he is ready to change and greatly injure a tragic story, given him by long tradition, in order that a loving pair may not be permanently separated. One apparent exception there is—the story of Rama and Sita in The Dynasty of Raghu. In this case it must be remembered that Rama is an incarnation of Vishnu, and the story of a mighty god incarnate is not to be lightly tampered with.

It is perhaps an inevitable consequence of Kalidasa’s subject that his women appeal more strongly to a modern reader than his men. The man is the more variable phenomenon, and though manly virtues are the same in all countries and centuries, the emphasis has been variously laid. But the true woman seems timeless, universal. I know of no poet, unless it be Shakespeare, who has given the world a group of heroines so individual yet so universal; heroines as true, as tender, as brave as are Indumati, Sita, Parvati, the Yaksha’s bride, and Shakuntala.

Kalidasa could not understand women without understanding children. It would be difficult to find anywhere lovelier pictures of childhood than those in which our poet presents the little Bharata, Ayus, Raghu, Kumara. It is a fact worth noticing that Kalidasa’s children are all boys. Beautiful as his women are, he never does more than glance at a little girl.

Another pervading note of Kalidasa’s writing is his love of external nature. No doubt it is easier for a Hindu, with his almost instinctive belief in reincarnation, to feel that all life, from plant to god, is truly one; yet none, even among the Hindus, has expressed this feeling with such convincing beauty as has Kalidasa. It is hardly true to say that he personifies rivers and mountains and trees; to him they have a conscious individuality as truly and as certainly as animals or men or gods. Fully to appreciate Kalidasa’s poetry one must have spent some weeks at least among wild mountains and forests untouched by man; there the conviction grows that trees and flowers are indeed individuals, fully conscious of a personal life and happy in that life. The return to urban surroundings makes the vision fade; yet the memory remains, like a great love or a glimpse of mystic insight, as an intuitive conviction of a higher truth.

Kalidasa’s knowledge of nature is not only sympathetic, it is also minutely accurate. Not only are the snows and windy music of the Himalayas, the mighty current of the sacred Ganges, his possession; his too are smaller streams and trees and every littlest flower. It is delightful to imagine a meeting between Kalidasa and Darwin. They would have understood each other perfectly; for in each the same kind of imagination worked with the same wealth of observed fact.

I have already hinted at the wonderful balance in Kalidasa’s character, by virtue of which he found himself equally at home in a palace and in a wilderness. I know not with whom to compare him in this; even Shakespeare, for all his magical insight into natural beauty, is primarily a poet of the human heart. That can hardly be said of Kalidasa, nor can it be said that he is primarily a poet of natural beauty. The two characters unite in him, it might almost be said, chemically. The matter which I am clumsily endeavouring to make plain is beautifully epitomised in The Cloud-Messenger. The former half is a description of external nature, yet interwoven with human feeling; the latter half is a picture of a human heart, yet the picture is framed in natural beauty. So exquisitely is the thing done that none can say which half is superior. Of those who read this perfect poem in the original text, some are more moved by the one, some by the other. Kalidasa understood in the fifth century what Europe did not learn until the nineteenth, and even now comprehends only imperfectly: that the world was not made for man, that man reaches his full stature only as he realises the dignity and worth of life that is not human.

That Kalidasa seized this truth is a magnificent tribute to his intellectual power, a quality quite as necessary to great poetry as perfection of form. Poetical fluency is not rare; intellectual grasp is not very uncommon: but the combination has not been found perhaps more than a dozen times since the world began. Because he possessed this harmonious combination, Kalidasa ranks not with Anacreon and Horace and Shelley, but with Sophocles, Vergil, Milton.

He would doubtless have been somewhat bewildered by Wordsworth’s gospel of nature. “The world is too much with us,” we can fancy him repeating. “How can the world, the beautiful human world, be too much with us? How can sympathy with one form of life do other than vivify our sympathy with other forms of life?”

It remains to say what can be said in a foreign language of Kalidasa’s style. We have seen that he had a formal and systematic education; in this respect he is rather to be compared with Milton and Tennyson than with Shakespeare or Burns. He was completely master of his learning. In an age and a country which reprobated carelessness but were tolerant of pedantry, he held the scales with a wonderfully even hand, never heedless and never indulging in the elaborate trifling with Sanskrit diction which repels the reader from much of Indian literature. It is true that some western critics have spoken of his disfiguring concerts and puerile plays on words. One can only wonder whether these critics have ever read Elizabethan literature; for Kalidasa’s style is far less obnoxious to such condemnation than Shakespeare’s. That he had a rich and glowing imagination, “excelling in metaphor,” as the Hindus themselves affirm, is indeed true; that he may, both in youth and age, have written lines which would not have passed his scrutiny in the vigour of manhood, it is not worth while to deny: yet the total effect left by his poetry is one of extraordinary sureness and delicacy of taste. This is scarcely a matter for argument; a reader can do no more than state his own subjective impression, though he is glad to find that impression confirmed by the unanimous authority of fifty generations of Hindus, surely the most competent judges on such a point.

Analysis of Kalidasa’s writings might easily be continued, but analysis can never explain life. The only real criticism is subjective. We know that Kalidasa is a very great poet, because the world has not been able to leave him alone.

ARTHUR W. RYDER.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

On Kalidasa’s life and writings may be consulted A. A. Macdonell’s History of Sanskrit Literature (1900); the same author’s article “Kalidasa” in the eleventh edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica (1910); and Sylvain Lévi’s Le Théâtre Indien (1890).

The more important translations in English are the following: of the Shakuntala, by Sir William Jones (1789) and Monier Williams (fifth edition, 1887); of the Urvashi, by H. H. Wilson (in his Select Specimens of the Theatre of the Hindus, third edition, 1871); of The Dynasty of Raghu, by P. de Lacy Johnstone (1902); of The Birth of The War-god (cantos one to seven), by Ralph T. H. Griffith (second edition, 1879); of The Cloud-Messenger, by H. H. Wilson (1813).

There is an inexpensive reprint of Jones’s Shakuntala and Wilson’s Cloud-Messenger in one volume in the Camelot Series.

KALIDASA

-

- An ancient heathen poet, loving more

- God’s creatures, and His women, and His flowers

- Than we who boast of consecrated powers;

- Still lavishing his unexhausted store

-

- Of love’s deep, simple wisdom, healing o’er

- The world’s old sorrows, India’s griefs and ours;

- That healing love he found in palace towers,

- On mountain, plain, and dark, sea-belted shore,

-

- In songs of holy Raghu’s kingly line

- Or sweet Shakuntala in pious grove,

- In hearts that met where starry jasmines twine

-

- Or hearts that from long, lovelorn absence strove

- Together. Still his words of wisdom shine:

- All’s well with man, when man and woman love.

Goethe.

- Willst du die Blüte des frühen, die

- Früchte des späteren Jahres,

- Willst du, was reizt und entzückt,

- Willst du, was sattigt und nährt,

- Willst du den Hummel, die erde mit

- Einem Namen begreifen,

- Nenn’ ich, Sakuntala, dich, und

- dann ist alles gesagt.

[1 ]These verses are translated on pp. 123, 124.

[2 ]The passage will be found on pp. 190-192.

[1 ]This matter is more fully discussed in the introduction to my translation of The Little Clay Cart (1905).

[1 ]Lévi, Le Théâtre Indien, p. 163.