Collected Works of Bastiat, vol. 5: Economic Harmonies

Collected Works of Frédéric Bastiat: Vol. 5 Economic Harmonies

[Created: Feb. 20, 2019]

|

|

|

Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850)

|

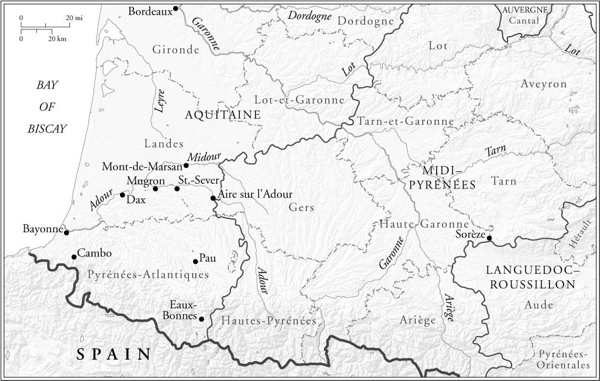

Map of Les Landes in SW France

|

Introduction

This is a final draft of the text with footnotes (but not the bibliography, glossaries and Appendix) as of 20 Feb. 2019.

Please note the following:

- this is an "Editor's Final Draft" which will be tidied up and properly formatted by our in-house editor, especially things like data tables

- what we do not have here is the Front Matter and Introduction

- the internal references have been left blank deliberately (e.g., see, pp. 000.) as they are place-holders

- the quotes are side-by-side in French and English for research purposes. Only English quotes will apper in the final version

For more information about Frédéric Bastiat see the following:

- Summary of the Bastiat Project

- Works in the OLL by Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850)

- A Reader's Guide to the Works of Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850)

- A Chronological List of Bastiat's Writings

-

The Collected Works of Frédéric Bastiat. In Six Volumes (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2011 -2015), General Editor Jacques de Guenin. Academic Editor Dr. David M. Hart.

- Vol. 1: The Man and the Statesman. The Correspondence and Articles on Politics (March 2011) - published book version

- Vol. 2: "The Law," "The State," and Other Political Writings, 1843-1850 (June 2012) - published book version

- Vol. 3: Economic Sophisms and "What is Seen and What is Not Seen" (March, 2017) - published book version

- Vol. 4: Miscellaneous Works on Economics (June 2017) - final draft version

- Vol. 5: Economic Harmonies (February 2019) - final draft version

- Vol. 6: The Struggle Against Protectionism: The English and French Free-Trade Movements (forthcoming)

Table of Contents

Front Matter

- Introduction to the Volume (to come)

1. Economic Harmonies: Introductory Material

- Draft Preface for the Harmonies (1847)

- A Lecture on Free Trade and related Economic Questions (3 July 1847)

- A Note on Economic and Social Harmonies (c. early 1850)

2. Economic Harmonies (1850 ed.)

- To the Youth of France

- I. Natural and Artificial Organisation

- II. Needs, Efforts, and Satisfactions (of needs)

- III. On the Needs of Man

- IV. Exchange

- V. On Value

- VI. Wealth

- VII. Capital

- VIII. Property and Community

- IX. Property in Land

- X. Competition

- Conclusion of the 1st Edition of the Harmonies

3. Economic Harmonies (2nd 1851 ed.)

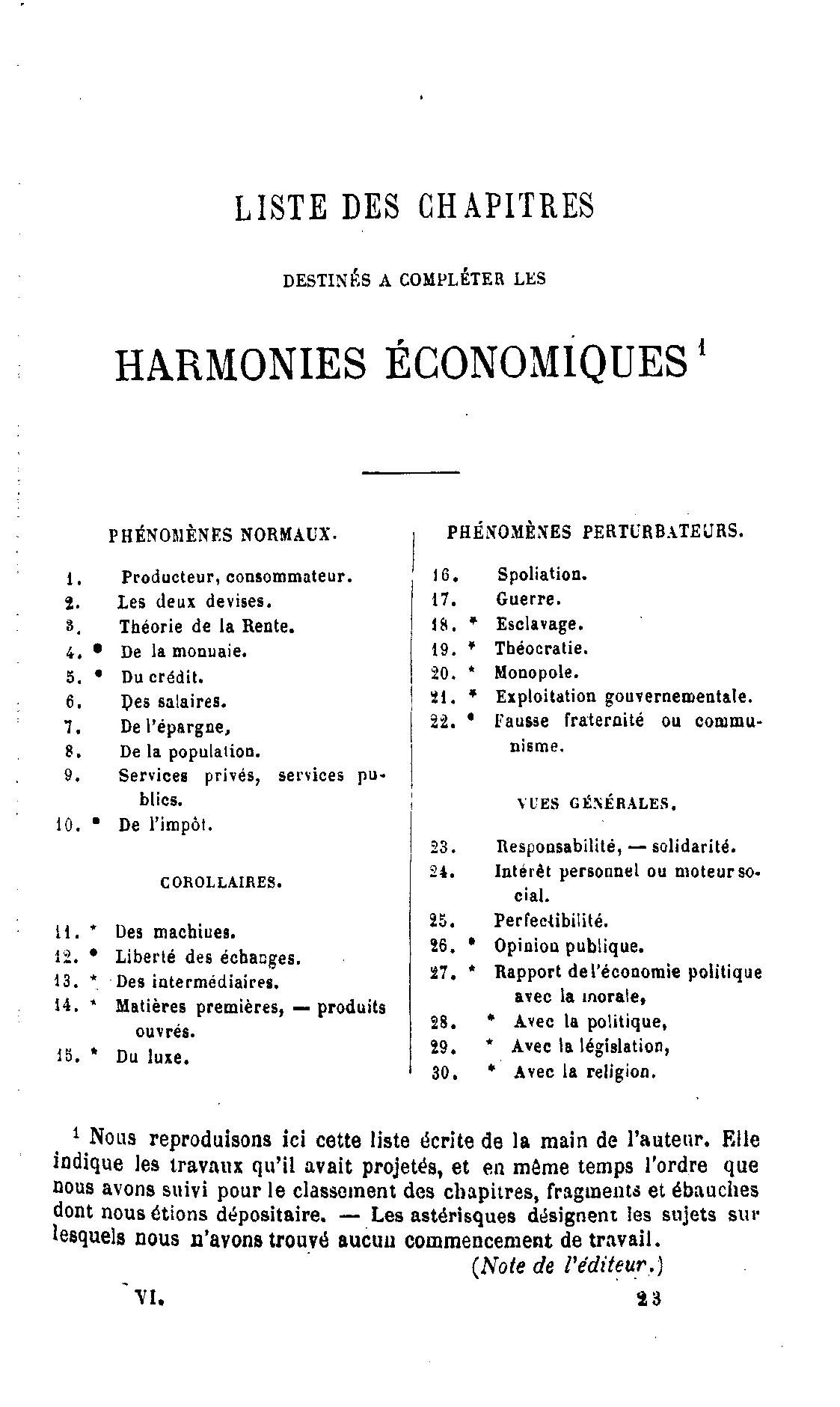

- List of Chapters intended to complete the Economic Harmonies

- XI. Producer (and) Consumer

- XII. Two Sayings

- XIII. On Rent

- XIV. On Wages

- XV. On Saving

- XVI. On Population

- XVII. Private and Public Services

- XVIII. Disturbing Factors

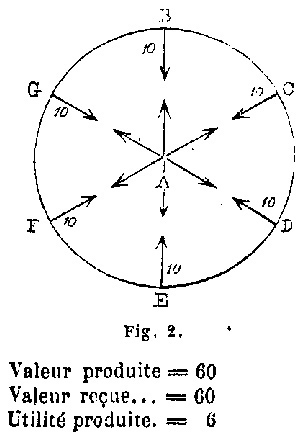

- XIX. War

- XX. Responsibility

- XXI. Solidarity

- XXII. The Driving Force of Society

- XXIII. Evil

- XXIV. Perfectibility.

- XXV. The Relationship of Political Economy with Morality, with Politics, with Legislation, and with Religion

4. Economic Harmonies (Additional Material)

Glossaries (to come)

Appendix 1: Further Aspects of Bastiat's Thought (to come)

Bibliography (to come)

1. Economic Harmonies: Introductory Material

Draft Preface for the Harmonies (1847) ↩

Source

OC, vol. 7, p. 303-09. CW, vol. 1, pp. 316-20. Reprinted here because it really belongs with the Ec.Harmonies.

Editor’s Introductory Note

According to Paillottet, this draft preface, which is in the form of an ironic letter to himself (Bastiat), was written sometime in late 1847 while he was giving lectures to some young students in the Faculty of Law. It reads very much like the letters he and his closest friend from Mugron, Félix Coudroy, must have written in the 1820s, giving each other advice and consolation in the face of their doubts about studying various treatises of economics.[1]

Bastiat had started giving lectures on economics to some law students at the Taranne Hall in Paris in July 1847 using the first collection of his Economic Sophisms (published in Jan. 1846) as the textbook.[2] These lectures would later be turned into his treatise which eventually became Economic Harmonies. His course of lectures were interrupted by the outbreak of revolution in February 1848 and Bastiat never returned to lecturing. The preface refers to the book as “les Harmonies” (the Harmonies) because his original rather grand plan was to write a general treatise on Social Harmonies which would cover society as a whole. Since this turned out to be too ambitious given his political activities during the Second Republic and his failing health he decided to limit it to just the Economic Harmonies.[3] His planned chapters for the expanded version of the book were complied by Paillottet and inserted at the end of his conclusion of the first edition of the book.[4] We have attempted to reconstruct what his three-volume treatise would look like from his scattered remarks in letters and essays:[5]

- volume one would be a general theory of how human society functions, to be called Social Harmonies with chapters on things like responsibility, solidarity, self interest, perfectibility, morality, and legislation

- volume two on his economic theory, to be called Economic Harmonies with chapters on topics much like we see in the published version but with additional chapters on taxation, the machinery question, free trade, on middlemen, raw materials and finished products, and on luxury

- volume three on the disturbing factors or “disharmonies” which disrupted the harmonies discussed in the first two volume. Tis volume was to be called The History and Theory of Plunder with chapters on plunder, war, slavery, theocracy, monopoly, governmental exploitation, "false fraternity" or communism

Text

My dear Frédéric,

So the worst has happened; you have left our village.[6] You have abandoned the fields you loved, the family home[7] in which you enjoyed such total independence, your old books which were amazed to slumber neglected on their dusty shelves, the garden in which on our long walks we chatted endlessly de omni re scibili et quibusdam aliis,[8] [9] this corner of the earth that was the sanctuary of so many people we loved and where we went to find such gentle tears and such dear hopes. Do you remember how the root of faith grew green again in our souls at the sight of these cherished tombs? With what proliferation did ideas spring to our minds inspired by these cypresses? We had barely given thought to them when they came to our lips. But none of this could keep you here. Neither these good ordinary country folk who appeared before (your) court and were accustomed to seeking decisions in your honest instincts rather than in the (letter of the) law,[10] nor our circle (of friends)[11] (among whom we enjoyed so many) puns and jokes that two languages were not enough for (all of) them[12] and where gentle familiarity and long-standing intimacy replaced fine manners,[13] nor your cello[14] which appeared to renew constantly the source of your ideas, nor my friendship, nor this “absolute empire”[15] (which dominates) your actions, your waking hours, and your studies, (which is) perhaps the most precious of (your) assets. You have left the village and here you are in Paris, in this whirlwind where as Hugo says: … [16]

Frédéric, we are accustomed to speaking to each other frankly. Very well! I have to tell you that your resolution surprises me, and what is more, I cannot approve of it. You have let yourself be seduced by the love of fame, I do not go so far as to say (love of) glory and you know very well why.[17] How many times have we not said that from now on glory would be the prize only of minds of an immense superiority! It is no longer enough to write with purity, grace, and warmth; ten thousand people in France do that already. It is not enough to have wit; wit is everywhere. Do you not remember that, when reading the smallest article, so often lacking in good sense and logic but almost always sparkling with verve and rich in imagination, we used to say to one another, “Writing well is going to become a faculty common to the species, like walking and sitting well.” How are you to dream of glory with the spectacle you have before your eyes? Who today thinks of Benjamin Constant or Manuel?[18] What has become of these reputations which appeared imperishable?

Do you think you can be compared to such great minds?

Have you undertaken the same studies as they? Do you possess their immense faculties? Have you, like them, spent your entire life among exceptionally brilliant people? Have you the same opportunities of making yourself known, or the same platform; are you surrounded when need arises with the same comradeship? You will perhaps say to me that if you do not manage to shine through your writings you will distinguish yourself through your actions. I say, look where that approach has left La Fayette’s reputation.[19] Will you, like him, have your name resound in the old world and the new for three quarters of a century? Will you live through times as fertile in events?[20] Will you be the most outstanding figure in three major revolutions?[21] Will it be given to you to make or bring down kings? Will you be seen as a martyr at Olmultz[22] and a demigod at the Hôtel de Ville? Will you be the general commander of all the National Guard regiments in the kingdom? And should these grand destinies be your calling, see where they end: in the casting among nations of a name without stain which in their indifference they do not deign to pick up; in their being overwhelmed with noble examples and great services which they are in a hurry to forget.

No, I cannot believe that pride has so far gone to your head as to make you sacrifice genuine happiness for a reputation which, as you well know, is not made for you and which, in any case, will be only fleeting. It is not you who would ever aspire to become the great man of the month in the newspapers of today.

You would deny your entire past. If this type of vanity had seduced you, you would have started by seeking election as a deputy.[23] I have seen you stand several times as a candidate but always refuse to do what is needed to succeed. You used constantly to say, “Now is the time to take a little action in public affairs, where you read and discuss what you have read. I will take advantage of this to distribute a few useful truths under the cover of candidacy,” and beyond that, you took no serious steps.

It is therefore not the spur of amour-propre that drove you to Paris. What then was the inspiration to which you yielded? Is it the desire to contribute in some way to the well-being of humanity? On this score as well, I have a few remarks to make.

Like you I love all forms of freedom; and among these, the one that is the most universally useful to mankind, the one you enjoy at each moment of the day and in all of life’s circumstances, is the freedom to work and to trade. I know that the acquisition of property is the fulcrum of society and even of human life (itself). I know that trade is intrinsic to property and that to restrict the one is to shake the foundations of the other. I approve of your devoting yourself to the defense of this freedom whose triumph will inevitably usher in the reign of international justice and consequently the extinction of hatred, prejudice between one nation and another, and the wars that come in their wake.

But in fact, are you entering the lists with the weapons appropriate for your fame, if that is what you are dreaming of, as well as for the success of your cause itself? What are you concerned with, I mean really concerned with? A proof, and the solution to a single problem, namely: Do trade restrictions add to the profit column or the loss column in a nation’s accounts? That is the subject on which you are exhausting your entire mind! Those are the limits you have set around your great question! Pamphlets, books, brochures, articles in newspapers, speeches, all of these have been devoted to removing this gap in our knowledge: will freedom give the nation one hundred thousand francs more or less? You seem to be very determined to sweep under the carpet any insights which only shine indirect light on this theorem. You seem set on extinguishing in your heart all these sacred flames which a love for humanity once lit there.

Are you not afraid that your mind will dry up and wither with all this analytical work, this endless argumentation focused on mathematical calculations?[24]

Remember what we so often said: unless you pretend that you can bring about progress in some isolated branch of human knowledge or, rather, unless you have received from nature a cranium distinguished only by its imperious forehead, it is better, especially in the case of mere amateur philosophers like us, to let your thinking roam over the entire range of intellectual endeavor rather than enslave it to the solving of one problem. It is better to search for the relationships between the sciences and the harmony of the social laws, than to wear yourself out shedding light on a doubtful point at the risk of even losing the sense of what is grand and majestic in the whole.

This was the reason our reading was so varied and why we took such care in shaking off the yoke of conventional opinion. Sometimes we read Plato, not to admire him according to the faith of the ages but to assure ourselves of the radical inferiority of society in ancient times, and we used to say, “Since this is the height to which the finest genius of the ancient world rose, let us be reassured that man can be perfected and that faith in his destiny is not misguided.” Sometimes we were accompanied on our long walks by Bacon, Lamartine, Bossuet, Fox, Lamennais, and even Fourier.[25] Political economy was only one stone in the social edifice we sought to construct in our minds, and we used to say: “It is useful and fortunate that patient and indefatigable geniuses, like Say,[26] concentrated on observing, classifying, and setting out in a methodical order all the facts that make up this beautiful science. From now on, (our) minds can stand securely on this unshakeable base and lift ourselves up to (see) new horizons.” How much did we also admire the work of Dunoyer and Comte,[27] who, without ever deviating from the rigorously scientific line drawn by M. Say, applied with such delight these accepted truths to the domains of moral theory and legislation. I will not hide from you that sometimes, in listening to you, it seemed to me that you could in your turn take this same torch from the hands of your (intellectual) predecessors and cast its light in certain dark corners of the social sciences, above all in those which foolish doctrines have recently plunged into darkness.

Instead of that, here you are, fully occupied with illuminating a single one of the economic problems that Smith and Say have already explained a hundred times better than you could ever do. Here you are, analyzing, defining, calculating, and making distinctions. Here you are, scalpel in hand, seeking out what there is of worth in the depths of the words price, value, utility, high prices, low prices, imports, and exports.

But finally, if it is not for you yourself, and if you do not fear becoming dazed by the task, do you think you have chosen the best plan to follow in the interest of the cause? People are not governed by equations but by generous instincts, by feelings, and sympathy for others. It was necessary to show them the successive dismantling of the barriers which divide men into mutually hostile communities, into jealous provinces, or into warring nations. It was necessary to point out to them the merging of races, interests, languages, and ideas; the triumph of truth over error as a result of the collision between minds; progressive institutions replacing the regime of absolute despotism and hereditary castes; wars eliminated, armies disbanded, and moral power replacing physical force; and the human race preparing itself for the destiny reserved for it by uniting together. This is what would have impassioned the masses, and not your dry proofs.

In any case, why limit yourself? Why imprison your thoughts? It seems to me that you have subjected them to a prison diet of a single crust of dry bread as food, since there you are, chewing night and day on a question of money. I love commercial liberty as much as you do. But is all human progress encapsulated in that (one kind of ) freedom? In the past, your heart beat (faster) for the freeing of thought and speech which were still chained by the shackles imposed by the university system and the laws against free association. You enthusiastically supported parliamentary reform and the radical division of that sovereignty, which delegates and controls, from the executive power in all its branches. All forms of freedom go together. All ideas form a systematic and harmonious whole, and there is not a single one whose proof does not serve to demonstrate the truth of the others. But you act like a mechanic who makes a virtue of explaining an isolated part of a machine in the smallest detail, not forgetting anything. The temptation is strong to cry out to him, “Show me the other parts; make them work together; each of them explains the others. ..”[28]

A Lecture on Free Trade and related Economic Questions (3 July 1847)↩

Source

"Réunion de la rue Taranne," Le Libre-échange, 4 July 1847, no. 32, pp. 252-53.[29] This was republished as “Troisième discours, à Paris” (Third Speech given in Paris at the Taranne Hall) (3 juillet 1847) [OC2.44, p. 246]. The OC version did not include the introduction and conclusion which we reproduce here. The LE version contained material by the unnamed editor who signed the article “J.”

Text

[Introduction by one of the editor’s of Le Libre-échange.]

Last Wednesday evening (3 July 1847) a large group of young gentlemen, most of whom came from the School of Law, squeezed into the hall at no. 12 Taranne street to hear M. Frédéric Bastiat. He had offered to speak to the young students from the (law and medical) schools[30] about some general observations concerning the subject of free trade, which has been so poorly studied up until now and thus so poorly understood. M. Bastiat wished above all to demonstrate the necessity of adhering to (matters of) principle, every time one touched on matters with the gravity of those dealt with by the (French) Free Trade Association); and (to expose) the inconsistencies into which the partisans of trade protection were led by their system (based upon) expediency. M. Bastiat then showed the connection which existed between discussions about the question of free trade and those of several other social problems of great interest, as well as the usefulness that youth (such as them) would find in making it the subject of their attention. The audience followed this exposition with great attention and an interest which was truly encouraging for the speaker. When M. Bastiat had finished the audience showed its appreciation with unanimous applause.

Below are some passages from M. Bastiat’s lecture.

Gentlemen,

For some time now I have very much wanted to be here with you. On many occasions when I was intellectually sure of the evidence and felt the need to express myself, which is an integral part of any belief with regard to questions of interest to the human race, I have said to myself: “Why can I not speak to the young people in the universities, for words are the seed that sprouts and bears fruit, especially in young minds.” The more you observe the ways of nature, the more you admire the harmony of their interconnections. For example, it is perfectly clear that the need for education is felt more keenly at the start of life. For this reason, you can see with what amazing industry life has placed the capacity and desire to learn at this time and not just ensured the suppleness of our mind, the freshness of our memory, the prompt assimilation of concepts, the power of attention, and the physiological qualities that are the fortunate privilege of (people) your age, but also the indispensable moral aptitude of discerning the true from the false, and by this I mean (a sense of) disinterestedness.[31]

Far be it fo me to satirize the generation to which I belong. However, I may say, without causing it offence, that it is less capable of shaking off the yoke of the errors that dominate (it). Even in the natural sciences, those that do not affect (our) passions, progress finds it very hard to be accepted. Harvey[32] used to say that he had never encountered a doctor more than fifty years old who wanted to believe in the circulation of the blood. I use the word “wanted to’ because, according to Pascal, “the will is one of the major organs of belief.”[33] And as interest acts on the disposition of (the) will, is it surprising that men whose age confronts them with the difficulties of life, who have reached the time (in their life) to take action, who act in accordance with deep-rooted convictions, and who have carved out for themselves a path in the world, reject instinctively a doctrine that might upset their arrangements and in the end only believe in what it is useful for them to believe?

This is not the case for the age group whose goal is study and examination. Nature would have gone against its own plans, if it had not made this age group disinterested. For example, it is possible that the doctrine of free trade upsets the interests of a few of you or at least of your families. Well, then! I am certain that this obstacle that is insurmountable elsewhere is not an obstacle in this hall. This is why I have always wanted to come here to discuss things with you.

And yet as you will understand, I cannot consider going into the detail or even dealing with the question of free trade today. One session would not be enough. My sole object is to show you how important it is and how closely linked it is with other extremely serious matters, in order to generate in you the desire to study it.

One of the most frequent accusations made against the Association for Free Trade[34] is that it does not limit itself to demanding a few timely modifications of the tariffs, but proclaims the very principle of free trade. This principle is scarcely contested; it is respected and saluted when it passes, but it is allowed to pass by. (However), people do not want it at any price, nor any of those who support it. What decided me to choose this subject are the events that have just occurred in a recent election[35] and which may be summarized in the following dialogue between the electors and the candidate:[36]

“You are an honorable man; your political opinions are the same as ours. Your character inspires us with total confidence and your past record is a guarantee to us of your future behaviour; however, you want to reform the tariffs.”

“Yes.”

“We want that too. You want it to be prudent and gradual.”

“Yes.”

“We see it this way too. But you link it to a principle, which you express in the words, free trade.”

“Yes.”

“In that case you are not the man for us. (Laughter) We have a host of other candidates who promise us both the advantages of freedom and the comforts of (trade) restriction. We will choose one of them.”

Gentlemen, I believe that one of the great misfortunes and great dangers of our age is this inclination to reject principles,[37] which after all are just the logical reasoning of the mind. In rejecting these, men of conviction are discouraged (from seeking office). They are led to insert into their election manifestos ambiguous phrases intended to satisfy, or at least half-satisfy, the most conflicting opinions. You cannot enter into public life through this door without sullying the purity of your conscience. I know full well how a candidate faced with these requirements reasons. He tells himself: “Just this once I will abandon the principle and resort to expediency. It is a question of winning. But once I have been nominated I will go back to the full sincerity of my convictions.” Yes, but when you have taken the first step along the dangerous path of compromise, there is always a good reason for deciding to take a second until in the end, even when external circumstances allow you full freedom of action, the evil has penetrated into conscience itself, and you find that you have stepped down from the level of rectitude you would have wanted to maintain. And see the consequences! Complaints are made on all sides and people say: “The conservatives have no plan and the opposition have no programme. If you go back to the cause, perhaps you will find it in the minds of the electorate itself, which requires candidates to renounce principles, that is to say, any fixed idea, any logic, and any belief.

And certainly, if there is one right that can be claimed as a right, that is to say that conforms to a principle, it is truly the freedom to trade.

As we have said in our (Free Trade) manifesto, we consider trade not only as a corollary of property, but as something that is an integral part of property itself, one of its constituent elements.[38] It is impossible for us to consider as a property (right) in the things that two men have respectively created by their own work if these two men do not have the right to exchange them, even if one of them is a foreigner. And, as for the harm to the nation that, it is said, will result from this exchange, we cannot understand how you damage your country by selling to a foreigner the very thing that you have the right to consume and destroy, in return for an object of equivalent value.

I will go further. I state that trade is synonymous with Society.[39] What constitutes the sociability of men is the ability to divide up their occupations and join forces with each other, in a word, to exchange their services. If it were true that ten nations could increase their prosperity by isolating themselves from each other, this would also be true for ten departments. I challenge protectionists to produce an argument in favor of work at the national level that cannot be applied to work at the departmental level, the communal level, the family level, and finally the individual level, from which it follows that (trade) restriction, when taken to the limit, (results in) absolute isolation and the destruction of society.[40]

Our opponents, it is true, say that they do not go that far, that they restrict trade only in certain circumstances and when it suits them to do so. This is no justification for logical minds. Where we challenge them is not where they leave trade free, but where they forbid it. It is within these limits that we declare their principle to be false, harmful, an infringement of property (rights), and detrimental to society. They do not push it to the limit, it is true, and this is precisely what proves the absurdity that fails to support this proof.

You can see clearly that we are faced with a false principle. And with what can we oppose it, if not one that is true?

But, Gentlemen, I am one of those who think that when an idea has permeated a large number of people of good sense, when a sentiment, even one that is instinctive, is generally widespread, there must be something in these minds that explains and justifies them. This terror of free trade,[41] considered to be an absolute principle, a terror that has taken over the very people who want trade reform, has arisen from a misconception. Allow me to clear it up.

People assume that to want free trade in principle is to want trade not to be subject to restriction in any circumstances and under any pretext.

First of all, let us set aside trade that is immoral, fraudulent, and dishonest. It is the principal mission of the law and the right and duty of the government to repress any abuse of any activity, that of trade along with all the rest.

As for trade that does not contravene honesty, it may be restricted, we agree, for an exceptional reason. The principle is engaged only where (trade) restriction is decreed because of the advantage that is claimed to be found in (the) restriction itself.

If, for example, the state requires revenue[42] and cannot acquire enough by less burdensome means than taxing certain forms of trade, it is impossible to say that this tax contravenes the principle of freedom, any more than land taxes invalidate the principle of (private) property.[43] However, in this case everyone acknowledges that (trade) restriction is an inconvenience that is linked to the levying of the tax. From this to (having trade) restriction(s) for the sake of restricting trade, there is an infinite difference.

The carrying of letters is taxed on average at 45 centimes, and if I am not mistaken, brings 20 million francs into the Treasury.[44] But the Minister of Finance has never said that he has raised the tax to this level to prevent people from writing because communication by letter is intrinsically a bad thing. If he were able to count on the same revenue from a lower rate of tax, he would not hesitate to reduce it. But what would you think if he came to the rostrum to say: “It is disastrous in principle for people to write to each other and to prevent this, even at the sacrifice of the 20 million francs that I raise from this tax, I will increase it to 10, 50 or 100 francs, up to a level at which nobody would write any more letters. And as for the current revenue which would be compromised, I will compensate for it by inflicting other taxes on the people.”?

Gentlemen, do you not see that between this prohibitive tax and the current rate of tax there lies the principle itself, since, in the first case, people deplore that the tax restricts communicating by letter and in the second, on the contrary, the aim has been to destroy this communication systematically.

And this is the characteristic that we are combating in the Customs Service.[45] It restricts and prohibits (trade), not for any particular reason, such as to create resources for the Treasury, but on the contrary, it sacrifices Treasury revenue through an excessively high level of taxes, and even through prohibition, with the avowed, intentional, and systematic aim of preventing trade. As long as it acts in this way, it is expressly based on the anti-social principle of restricting trade. It seeks trade restriction for its own sake, considering it to be intrinsically good, and even so good that it warrants the pain of a sacrifice in revenue. It is to this principle that we are opposing the principle of freedom.

People are still looking for a way to alarm and terrify the general public by assuring them that what we want is to pass from one system to the other with no transition (period). What nonsense! And for how long will France be taken in by these strategic maneuvers by people who exploit (trade) restrictions?

All that we want is to make public opinion understand that the principle of freedom is just, true, and beneficial, and that the principle of (trade) restriction is iniquitous, false, and damaging.

We have never said and will never say that when you have taken the wrong path, you have to cover the distance separating you from the right path in a single leap.[46] What we say is that you have to turn around and retrace your steps, going toward the east instead of continuing to advance toward the west.

And should we demand instant reform, does this reform depend on us? Are we ministers (in the government)? Do we have a majority? Do we not have enough opponents and enough (vested) interests facing us to be sure that the reform will be slow, only too slow?

In what direction should we move? Should we move fast or slowly? These are two questions that are quite separate from one another, and which are not even linked. They are so little linked that, even though within our organization we all agree on the goal to be attained, we may have differing opinions on a suitable length of time for the transition. What we are unanimous about is to say that, since France is going down the wrong road, it has to be brought back with as little disturbance[47] as possible. The immense majority of our colleagues consider that this disturbance will be all the less if the transition is slow. Others, of whom I must admit that I am one, believe that the most sudden, instantaneous, and general reform would also be the least painful, and if this were the occasion to develop this thesis, I am sure that I would base it on reasons that you would find striking. I am not like the man from Champagne who told his dog: “Poor animal, I have to cut your tail off but do not worry, to spare you suffering I will organize the transition and will only cut a bit off every day.”[48]

However, and I repeat, the question for us is not to ascertain how many kilometers the reform will cover per hour; the only thing that concerns us is to persuade public opinion to take the route to freedom instead of the one to restriction. We see a coach team that claims to be going to the Pyrénées and which, in our view, is going in the opposite direction. We warn the coachman and the passengers, and in order to correct their error we make use of all we know of geography and topography; that is all.

There is one difference, however. When we prove to a coachman that he is mistaken, his error suddenly disappears, and he turns around as soon as he can. This is not true for trade reform. It can only follow the progress of public opinion, and in these matters this progress is slow and comes in stages. You can thus see that, as we ourselves admit, instantaneous reform, even if it were desirable, is impossible.

In the long run, Gentlemen, I am not too worried by this, and I will tell you why. It is because the enlightened minds that will be concentrated on the question of free trade through prolonged discussion will of necessity shed light on other economic questions that are extremely closely linked to free trade.

I will cite you a few examples.

For example, you know the old saying:[49] One man’s profit is another man’s loss.[50] The conclusion has been drawn that one nation can prosper only at the expense of other nations, and international politics, it has to be said, is based on this sorry maxim. How has this managed to become part of public certainty?

There is nothing that modifies the organization, institutions, customs, and ideas of a nation as profoundly as the general means through which they provide for their existence,[51] and there are just two of these means: plunder, taking this word in its widest sense, and production. For, Gentlemen, the resources that nature spontaneously offers people are so limited that they are able to live only on the products of human work, and they have either to create these products or take them by force from other people who have created them.[52]

The nations of antiquity, and in particular the Romans,[53] in whose company we have spent our entire youth and whom we have been accustomed to admire and constantly incited to imitate, lived from pillage. They detested and scorned work. War, loot, tribute, and slavery had to provide all that they consumed.

This was also true of the nations that surrounded them.

It is obvious that, in this social order, the maxim “one man’s profit is another man’s loss” was quite literally true. This has to be so between two men or two nations who seek to plunder each other reciprocally.[54]

Well, as we seek all of our initial impressions and ideas, all of our models and the subjects of our quasi-religious veneration from the Romans, it is hardly surprising that this maxim has been considered by our industrial societies as being the law governing international relations.

It forms the basis for the system (of trade restrictions), and if it were true, there would be no remedy for the incurable antagonism that it would have pleased Providence to instill in nations.

However, the doctrine of free trade demonstrates rigorously and mathematically the truth of the opposite axiom, which is: “Harm to one is harm to the other, and each nation has an interest in the prosperity of all.”[55]

I will not go here into this proof, which, incidentally, results from the sole fact that the nature of trade is quite opposite to that of plunder. But your wisdom will enable you to grasp instantly the major consequences of this doctrine and the radical change that it would introduce into the policies of nations if it managed to win their universal assent.

If it were properly proven, as a geometrical theorem is proven, that even though it upsets those who carry out a similar industry in other nations, any progress made by a nation in a particular sector of industry is nonetheless favorable to their interests as a whole, what would happen to the dangerous efforts to achieve pre-eminence, the jealousies between nations, the wars to obtain markets, etc. and consequently, the standing armies,[56] all of which are without doubt the remnants of savagery?

[Editorial interjection: The speaker at this point mentions a few questions of extreme gravity on which a discussion on free trade ought to shed a clear light, one of which is the fundamental problem of political science: What ought the limits of government action to be?][57]

By calling your attention to some of the serious problems raised by the question of free trade, I wanted to show you the importance of this question and the importance of economic science itself.

For some time, a number of writers have risen up against political economy, and they believed that to decry it it was enough to change its name. They called it economism.[58] Gentlemen, I do not think that the truths proved by geometry would be shaken by calling it geometrism.

It is accused of concerning itself only with wealth, and thus to drag the human mind down to the ground. It is especially in front of you (today) that I am determined to rid it of this criticism, for you are of an age at which it is natural to make a vivid impression.

First of all, even if it were true that political economy concerned itself exclusively with the way in which wealth was formed and distributed, this would already be a vast science if the word wealth is taken in its accepted scientific meaning and not in its popular one. In popular thinking, the word wealth implies the notion of superfluous (or unnecessary) things. Scientifically, wealth is the total number of reciprocal services[59] that people render to each other and through which society exists and develops. The progress of wealth means more bread for those who are hungry and clothing that not only protects from extremes of weather but also gives people a feeling of dignity. Wealth means more leisure time,[60] and consequently intellectual culture. For a nation it provides the means of repelling foreign aggression, for old people, ease in their retirement, and for a father, the ability to educate his son and provide a dowry for his daughter. Wealth is well-being, education, independence, and dignity.

But if it was considered that even in this expanded sphere political economy is a science that is too concerned with material interests, sight should not be lost of the fact that it leads to the solution to problems of a higher order, as you may have been persuaded when I called your attention to the following two questions: Is it true that one man’s profit is another man’s loss? What is the rational limit to the action of government?

But what will surprise you, Gentlemen, is that the socialists, who criticize us for being too concerned with the goods of this world, themselves show an exclusive and exaggerated cult of wealth in the opposition they put forward to free trade. What do they in fact say? They agree that free trade would have highly desirable results from a political and moral point of view. Nobody will deny that free trade tends to bring nations together, extinguish national hatreds, consolidate peace, and encourage the communication of ideas, the triumph of peace, and progress toward unity. What is the basis for their rejection of this freedom? The sole basis is that it would damage national labour, subject our industries to the inconveniences of foreign competition, decrease the well-being of the masses, or in a word, (our) wealth.

Faced with this objection, are we not obliged to deal with the economic question and demonstrate that our opponents are viewing competition from just a single angle and that free trade has as many advantages from a material point of view as from all the others? And when we do this we are told: “You are concerned only with wealth; you give too much importance to wealth.”

[Editor’s interjection: After having rejected the criticism made of political economy that it is a science imported from England, the speaker ends with the following words:]

Gentlemen, I will stop here, and perhaps I have already taken too much advantage of your patience. I will end by urging you with all my strength to devote a few moments of your leisure time to the study of political economy. Allow me to give you a further piece of advice. If ever you become members of the Free Trade Association or any other (group) with a goal that is of great public utility, do not forget that debates of this nature have public opinion[61] as their judge and that they want to be supported on the grounds of principle and not on that of expediency. I call “expediency,” as opposed to “principle,” the inclination to judge questions from the point of view of the circumstances of the moment, and even all too often from those of the interests of a class or (the interests of particular) individuals. An association needs a bond, and this bond can only be a principle. The mind needs a guide and enlightenment, and this can only be a principle. The human heart needs motivation to determine action, dedication, and sacrifice if need be, and you do not dedicate yourself to an expedient, but to a principle. Look at history, Gentlemen, and you will see the names that are dear to the human race and recognize that they are those of men driven by an ardent faith. I despair for my century and my country when I see the honor given to expediency, and the derision and ridicule reserved for principle, for nothing fine and beautiful has been accomplished in the world other than by dedication to a principle. These two forces are often in conflict, and it is all too frequent to see the man who represents matters of the moment triumph and the one that represents a general idea fail. Nevertheless, look further afield and you will see principle achieving its goal and expediency leaving no trace of its passage.

Religious history offers a wonderful example of this. It shows us principle and expediency confronting one another in the most memorable event ever witnessed by the world. Who has ever been more fully devoted to a principle, the principle of fraternity, than the founder of Christianity? He was devoted to the point of suffering persecution and scorn, abandonment and death for it. He did not appear to be concerned with the consequences but placed them in the hands of His Father, saying: “Thy will be done.”

The same story shows us the man of expediency side by side with this model. Caiaphas, fearing the fury of the Romans, compromises his duty, sacrifices the just, and says: “It is expedient (expedit) that one man should perish for the salvation of all.”[62] The man of compromise triumphs while the man of principle is crucified. But what was the result? Half a century later, the entire human race, Jews and Gentiles, Greeks and Romans, masters and slaves rallied to the doctrine of Jesus, and if Caiaphas had been alive at this time he might have seen a plow pass over the site on which the Jerusalem that he thought he had saved by a cowardly and criminal compromise once stood. (Prolonged applause).

[Concluding comments by editor “J.”:]

Just as our colleague finished, M. Jules Duval asked him if he would agree to allow a follower of socialism (like him) to make a few observations. As he was speaking he moved from the back of the hall where he had been seated towards the table where M. Bastiat had been sitting. M. Bastiat replied that he had only spoken about socialism very indirectly and only to support some of his points, and that he hadn’t even wanted to plumb the depths of the question of free trade at this meeting; and having said this he ceded the floor to M. Jules Duval.

M. Duval is one of the principle editors of La Démocratie pacifique, the daily paper for that “Social Science” discovered by Fourier.[63] We quickly realized that he had come to make a series of criticisms against the present organization of society and against the school of economics which he believed to be the author and the defender of everything which happens in the world. Free trade wasn’t ignored in this general criticism, and for the three quarters of an hour for which he spoke, he had the talent to summarize all the arguments which our opponents make against us on a daily basis. Nevertheless, (our) Phalansterian speaker granted that the free trade doctrine (would produce) (much) bounty and richness (only) when it had been remade and reorganized upon the basis of “Social Science.”

We are happy to acknowledge that M. Jules Duval spoke with real talent, but his speech, we also have to say, had no relationship to M. Bastiat’s, who had treated none of the points that he (Duval) had come to address and refute. We will add that all the arguments of M. Jules Duval are far from agreeing with the principles of the school to which he belongs, and that he seems to us to (have) been far too preoccupied with the desire to defend the protectionist party, whose views he faithfully reproduced.

Having seen that the hour was late, M. Frédéric Bastiat was not able to rebut the numerous claims made by M. Jules Duval. He limited himself to giving his listeners a copy of his book Economic Sophisms[64] in which he has undertaken (the task of) uprooting the grossest errors of the doctrine of protectionism. The meeting adjourned and each of the young gentlemen accepted a copy of this work and showed by their enthusiasm their desire to deepen their knowledge of the important questions to which their attention had been called.

A Note on Economic and Social Harmonies (c. early 1850)↩

Source

Undated note by Bastiat on the “Economic and Social Harmonies” found among his papers (c. June 1845). Ronce, pp. 227-8. It can also be found quoted in Fontenay’s “Notice” in OC1 (1862) and the Foreword to the 2nd ed. of Economic Harmonies (1851).[65]

Text

I had originally thought to begin with an exposition of the Economic Harmonies[66] and as a result to treat only purely economic subjects, such as value, property, wealth, competition, wages, population, money, credit, etc. Later, if I had had the time and the energy, I would have called the reader’s attention to a much larger subject, the Social Harmonies. It is here that I would have talked about human nature, the driving force of society,[67] responsibility, solidarity,[68] etc. … Having conceived the project in this fashion I had commenced work on it when I realised that it would have been better to merge rather than to separate these two different kinds of approaches. But then logic demands that the study of mankind should precede that of economics. However, there was not enough time: how I wish I could correct this error in another edition!… [69]

2. Economic Harmonies (1850 ed.)

To the Youth of France↩

A love of study, a need for something to believe in, a mind free from deeply rooted prejudice, a heart free of hatred, a zeal for spreading ideas, warm feelings towards one’s fellow beings, impartiality, self-sacrifice, good faith, an enthusiasm for all that is good, beautiful, simple, great, honest, religious: such are the precious attributes of youth. This is why I am dedicating this book to them. It will indeed be a sterile seed if it does not take root in the generous soil to which I am entrusting it.

I would have liked to offer you a (fuller) picture, but I am just giving you a sketch; (so) forgive me. Who can succeed in creating a work of some importance these days? This is an outline. When you see it, may one of you cry out, like the great artist: “Anch’ io son pittore!”[70] and seizing the brush, put color and flesh, light and shade, feeling and life onto this shapeless canvas.

Young people, you will find the title of this book very ambitious. Economic Harmonies! Have I aspired to reveal the plans of Providence in the social order and the (social) mechanism[71] of all the forces provided to the human race for the achievement of progress?

Certainly not, but I would like to set you on the path to this truth: that All legitimate interests are harmonious. This is the dominant idea in this book, and it is impossible not to recognize its importance.

It may have been fashionable for a while to laugh at what is called the social problem,[72] and it must be said that some of the solutions put forward were only worthy of some mocking laughter. But as for the problem itself, there is certainly nothing funny about it. It is the ghost of Banquo at Macbeth’s feast,[73] but it is not a mute ghost, and in a stentorian voice it cries out to a terrified society: Find a solution on pain of death!

Well, this solution, as you will easily understand, has to be very different, depending on whether (our) interests are naturally in harmony or in conflict.

In the first case, we must call for freedom, in the second, for coercion. In the first case it is enough not to interfere, in the other, you have to interfere out of necessity.

But freedom has just one form. When people are fully convinced that each of the molecules that make up a liquid carry within itself the force that results in the (liquid finding its own) level, they conclude that there is no simpler or surer means of obtaining this level than not to interfere with it. All those, therefore, who adopt as their staring point, (the idea that) Interests are in harmony, will also agree on the practical solution to the social problem: refrain from impeding and displacing these interests. [74]

By contrast, coercion manifests itself in an infinite number of forms and points of view. The schools of thought that start from the presupposition that Interests are in conflict, have therefore not yet done anything to solve this problem except for excluding freedom. It still remains for them to identify from the infinite number of forms of coercion the one that is right, if there can indeed be one. Then, as a final difficulty, they will still have to have this preferred form of coercion universally accepted by people, by freely acting individuals.[75]

However, within this perspective, if human interests are impelled by their (very) nature toward a fatal clash, and this clash cannot be avoided except by the chance invention of an artificial form of social order,[76] the fate of the human race is in extreme jeopardy, and the following questions are raised in fear and trembling:

1. Will we ever find a man who finds an acceptable version of coercion?

2. Will this man rally to his way of thinking all the countless schools of thought that have conceived different versions?

3. Will the human race allow itself to be subjected to this (version) which, according to the assumptions espoused, will be at odds with all individual interests?

4. Assuming that the human race allows itself to be attired in this particular garment, what will happen when a new inventor comes along with (an) even better one?[77] Should it continue with a bad system, knowing it to be bad, or should it take the decision to change the arrangements every morning in line with the whims of fashion and the fertile imaginations of inventors?

5. Won’t all the candidates whose plans have been rejected band together against the plan selected, with all the more chance of upsetting society because this plan, by its very nature and aim, ruffles all types of interest?

6. And, in the final analysis, is there a human force capable of overcoming a conflict thought to constitute the very essence of human forces?

I could multiply these questions indefinitely and, for example, raise the following difficulty:

If individual self-interest is opposed to the general interest, where would you place the source of the coercion? Where would its fulcrum lie? Would it be outside the human race? It would have to be if it were to escape the consequences of your central principle. For in order to entrust arbitrary power to men, you would have to prove that, the men in question are made of a different clay from (the rest of) us, that they are not also moved by the fatal principle of self-interest, and that if they were placed in a situation excluding any idea of (there being) a brake on or any effective resistance to (their power), their minds would be free from any kind of error, their hands free from greed, and their hearts from any covetousness.[78]

What separates the various socialist schools[79] (by which I mean those that seek an artificial system of organization to cure the problem of society) radically from the school of the economists[80] is not this or that view of points of detail, this or that set of government arrangements, but the point of departure, the following preliminary and over-riding question: Are the interests of human beings, when left to themselves, in harmony or in conflict?

It is clear that socialists have been in a position to start seeking an artificial system of organization only because they considered the natural system to be bad or inadequate, and that they have judged the natural system to be inadequate or bad only because they thought they could see a fundamental conflict of interests, for if this were not the case they would not have had recourse to coercion. It is not necessary to force harmony on something intrinsically harmonious.

For this reason, they have seen conflict everywhere:

Between (the factory) owner and the proletarian,

Between capital and labor,

Between the people and the bourgeoisie,

Between agriculture and manufacturing,

Between country and city dwellers,

Between the native born citizens and foreigners,

Between producers and consumers,

Between civilization and organization[81]

In a word,

Between freedom and harmony.

And this explains how it can be that, while a kind of sentimental philanthropy dwells in their hearts, hatred flows from their lips. Each of them reserves his entire stock of goodwill for the society of his dreams, but as for the one in which we must live, for them it could not be overturned soon enough and thus make way for the new Jerusalem which will arise from its ashes.

I have said that the school of the economists, setting out from the premise of natural harmony of interests, has declared in favor of freedom.

However, I have to agree that while economists in general are in favor of freedom, it is unfortunately not equally true that their principles (have) established the starting point firmly enough, namely, the harmony of interests.

Before going any further, and in order to warn you against the inferences that this admission is bound to generate, I have to say something about the respective situations of socialism and political economy.

I would be foolish to say that socialism has never come up with any truth or that political economy has never fallen into error.

What profoundly separates the two schools of thought is the difference in their methods. One, like astrology and alchemy, proceeds by imagination; the other, like astronomy and chemistry, proceeds by observation.

Two astronomers observing the same fact may not come to the same conclusion.

In spite of this temporary disagreement, they feel bound by the common form of procedure that, sooner or later, will bring the disagreement to an end. They recognize that they are members of the same denomination. But between the astronomer who observes and the astrologer who imagines, the abyss is unbridgeable, even though they may sometimes meet by chance.

This is also true for political economy and socialism.

Economists observe man, the laws of his nature, and the social relations that arise from these laws. Socialists think up a novel society and then (invent) a human heart to fit it

Well, if science does not make mistakes, scholars do. I do not deny, therefore, that economists can make false observations, and I even add that of necessity they must have started (off) by doing so.

However, this is what happens. If interests are in harmony it then follows that any observation incorrectly carried out leads logically to (the conclusion that there is) conflict. What then is the tactic of the socialists? It is to cull from the writings of the economists a few incorrect observations, show their full consequences, and prove how disastrous they are. Up to this point, they are within their rights. They then rail against the observer, let’s say for example, Malthus or Ricardo.[82] They are still within their rights. But they do not stop there. They turn against (economic) science (itself), accusing it of being heartless and wanting harm[83] to occur. In doing this, they come up against reason and justice, for science is not responsible for observation (which is) badly carried out. Finally, they go very much further. They put the blame on society itself and threaten to destroy it in order to rebuild it, and why? Because, they say, science has proved that the current form of society is being driven toward an abyss. In doing this, they are contravening common sense, for either science does not make mistakes, so in this case why are they attacking it, or else it does makes mistakes, and so in this other case, let them leave society alone since it is not in jeopardy.

However, this tactic, illogical as it is, is nonetheless disastrous to economic science, especially if those working in it have the unfortunate habit of supporting each other’s ideas and the ideas of those who have gone before (in an uncritical fashion). Economic science is a queen whose allures ought to be frankly and freely discussed. The closed atmosphere which surrounds a clique will kill it.[84]

I have already said that it is not credible that any mistake in political economy must inevitably lead to conflict. On the other hand, it is impossible for the many articles written by economists, even the most eminent, not to include some wrong propositions. It is up to us to point them out and put them right in the interest of economic science and society. To persist stubbornly in supporting them for reasons of defending the honor of the school would be not only to expose ourselves, which is unimportant, but also to expose truth itself, which is more serious, to the blows of socialism.

I (will) return to my subject, therefore, and state: Economists advocate freedom. However, in order for this conclusion to obtain the approval of the hearts and minds (of others), it has to be firmly based on the following premise: Interests, (when) left to themselves, tend to form harmonious arrangements and tend to advance the general well-being in a progressive manner.

Well, several of these economists, among those whose authority is recognized, have advanced propositions that, step by step, lead logically to (the conclusions that) absolute evil (exists), (that) injustice is inevitable, that there is a fatal inequality which will get progressively worse, that pauperism is inevitable, etc.

This being so, there are very few, to my knowledge, who have not attributed value to natural resources (which are) the gifts that God has lavished on His creatures free of charge.[85] The word value implies that what contains it is handed over by us only in return for payment. You therefore have men, in particular landowners, selling the gifts of God in exchange for real labor and who are receiving payment for useful things in which their work has played no part. This is an obvious but necessary injustice, say these writers.[86]

Next we have the famous theory (of rent)[87] of Ricardo.[88] It can be summarized in this way:[89] The price for food is based on the labor needed to produce them on the poorest land being cultivated. Now, an increase in population obliges us to resort to increasingly infertile soil. For this reason, the entire human race (except for the landowners) is obliged to provide an ever-increasing amount of labor in exchange for the same quantity of food or, which amounts to the same thing, to receive an ever-decreasing quantity of food for the same amount of labor. At the same time, landowners see their rents increase each time land of lower quality is worked. The conclusion: The gradual increase in the opulence of men of leisure and the gradual impoverishment of working men, resulting in a fatal inequality.

Finally, Malthus’ even more famous theory (of population)[90] appeared.[91] Population tends to increase faster than the means of subsistence, and this has been true at every stage of existence of the human race. Well, people cannot be happy and live in peace if they do not have enough to eat. There are just two obstacles to this constantly menacing population surplus: a decrease in the birth rate or an increase in the mortality rate in all the dreadful forms in which this occurs. Moral constraint has to be universal if it is to be effective and nobody relies on this. For this reason, all that remains is the repressive or positive check:[92] namely, vice, poverty, war, plague, famine, and death, resulting in an inevitable pauperism.

I will pass over other less wide-ranging accounts which also result in a hopeless impasse. For example, Mr. de Tocqueville[93] and many like him say: If we accept the right of primogeniture[94] we come to an ever more concentrated form of aristocracy, and if we do not, we come to the division of land into smaller and smaller fractions and to a decrease in its productivity.[95]

And what is remarkable is that these four dreadful systems do not clash with one another. If they clashed we might console ourselves by thinking that they are all wrong, since they destroy one another mutually. On the contrary, they agree and form parts of the same general theory, which, supported by a number of plausible facts, appears to explain the convulsed state of modern society and, with the strong approval of several masters of economic science, presents itself to downcast and dejected minds, with terrifying authority.

It remains to be understood how the advocates of this sorry theory have been able to put forward the harmony of interests as a principle and freedom as a conclusion.

For it is clear that if the human race is fatally driven by the laws of value toward injustice, by the laws of rent toward inequality, by the laws of population toward poverty, and by the laws of inheritance toward the dying out of the species, then it should not be said that God has made the social world, like the physical world, a work of harmony; we have to admit with bowed heads that He was pleased to base it on a repulsive and incurable disharmony.[96]

Young people, you should not think that the socialists have refuted and rejected what I will call, so as not to offend anyone, the theory of disharmony.[97] No, whatever they say, they have held it to be true and it is precisely because they hold it to be true that they propose coercion as a substitute for freedom, an artificial form of organization for a natural form, and work of their own invention for the work of God. They tell their opponents (and in this, I do not know if they are not more consistent than the latter): If, as you have announced, human interests when left to themselves tend to combine harmoniously, we would have nothing better to do than to welcome and praise freedom, as you do. However, you have demonstrated incontrovertibly that if interests are left to develop freely, they propel the human race toward injustice, inequality, impoverishment, and dying out. Well then, we react against your theory precisely because it is true. We want to destroy society as it is today precisely because it obeys the fatal laws you have described. We want to try out our power since the power of God has failed.

Thus, we agree on the starting point and only the conclusion separates us.

The Economists to whom I refer say: The great laws of Providence are hurling society toward disaster; but you have to be careful not to disturb their action because this action is fortunately counteracted by other secondary laws,[98] which delay the final catastrophe, and any arbitrary intervention would only weaken the dam without stopping the fatal rising of the waters.

The Socialists say: The great laws of Providence are hurling society toward disaster; they have to be abolished and others chosen from our inexhaustible arsenal.

The Catholics say: The great laws of Providence are hurling society toward disaster; we have to escape from them by renouncing human self-interest and taking refuge in self-denial, sacrifice, asceticism, and resignation.

And, in the midst of this tumult, the cries of anguish and distress and the calls for subversion or for resigned despair, I am attempting to make the following statement heard, in the face of which, if it is justified, all disagreement ought to fade away: It is not true that the great laws of Providence are hurling society toward disaster.

Thus, all the schools of thought are divided and oppose one another with regard to the conclusions that have to be drawn from their common premise. I deny this premise. Is this not the way to stop the division and conflict?

The dominant idea in this work, the harmony of interests, is simple. Is not simplicity the touchstone of truth? The laws governing light, sound, and movement appear to us to be all the more true because they are simple; why should this not be the case for the law governing our self-interest?

It is conciliatory. What is more conciliatory than that which shows the agreement which exists between industries, classes, nations, and even doctrines?

It is consoling, because it points out what is wrong in the systems whose conclusion is that harm gets progressively worse.

It is religious, because it tells us that it is not only the workings of heaven but also those of society that reveal the wisdom of God and tell of His glory.

It is practical, and certainly nothing more easily put into practice than this can be conceived: Let us leave people (free) to work, exchange, learn, form associations with each other, and to act and react with one another, since, in accordance with providential decree, nothing other than order, harmony, progress, good, more good, and even more, indeed infinite good can flow from people’s thoughtful spontaneity.

“Here is a good example,” you will say, “of economists’ optimism![99] They are such slaves of their own systems that they shut their eyes to the facts for fear of seeing them. Faced with all the poverty, injustice, and oppression that afflicts the human race, they calmly deny the existence of evil. The whiff of gunpowder during insurrections does not reach their blasé senses.[100] The cobblestones of the barricades are not part of their vocabulary, and when society crumbles they will still be crying ‘Everything is for the best in the best of all worlds.’ ”[101]

No, certainly, we do not think that everything is for the best.

I do have total faith in the wisdom of providential laws, and for this very reason I have faith in freedom.

The question is to ascertain whether (or not) we have freedom.

The question is to know whether these laws can act to their full effect or if their action is not profoundly impaired by (some) opposing action from human institutions.

Denying the existence of harm! Denying the existence of suffering! Who could do such a thing? You would have to forget that we were speaking about human beings. You would have to forget that we ourselves are human beings. For the laws of providence to be held to be harmonious, it is not necessary for them to exclude harm. It is enough for this harm to have an explanation and a purpose, for it to be be self-limiting, for its own action to destroy it, and for each suffering to prevent a greater suffering by eliminating its own cause.[102]

The basis of society is man, who is a free force.[103] Since man is free, he is able to choose. Since he is able to choose, he may make mistakes. Since he is able to make mistakes, he may suffer.

I will go further. He has to make mistakes and suffer, for his starting point is ignorance, and in the face of ignorance an infinite number of unknown paths open up, all of which lead to error except for one.

Now, all error generates suffering. This suffering either falls on him who is mistaken, and in this case it is a question of (taking) responsibility (for it). Or it afflicts innocent beings with the error, and in this case it incites the marvellous and responsive apparatus known as solidarity.[104]

The action of these laws, combined with the gift we have been given to associate effects with causes ought to bring us back, through suffering itself, to the path of good and truth.

Thus, not only do we not deny (the existence of) harm, but we also acknowledge that it has a mission both in the social order as well as the physical.

However, in order for it to accomplish this mission, solidarity must not be extended artificially so that responsibility is destroyed; in other words, freedom has to be respected.

If human institutions run contrary to divine laws in this regard, harm does not follow error any the less, but it is displaced.[105] It (harm) strikes where it ought not to strike; it now acts without warning; it does not provide any lesson; it no longer tends to limit itself and to destroy itself through its own action. It persists, it becomes worse, just as would happen in a physical sense if the sorry effects of the reckless actions and excesses committed by people in one hemisphere were felt only by those in the opposite hemisphere.

Well, this is precisely the tendency not only of the majority of our governmental institutions but also and above all of those we seek to impose as remedies for the harms that afflict us. On the philanthropic pretext of inculcating an artificial form of solidarity between men, responsibility is made increasingly inert and ineffective. Through the excessive intervention by the coercive power of the state, the relationship between work and reward is changed, the laws governing industry and exchange are disrupted, the natural development of education is attacked, capital and labor are led astray, ideas are perverted, absurd claims are inflamed, illusory hopes shine in men’s eyes, and an unheard of loss of human powers is caused. Centers of population are displaced, experience itself is made ineffective, in short, all all interests are given artificial foundations and set to fighting each other, and then people cry: “You see, interests are in conflict. It is freedom that is the root of all evil. Let us curse and stifle freedom.”

And meanwhile since this sacred word still has the power of making hearts beat faster, freedom is stripped of its prestige by the forcible loss of its name, and it is under the name of competition[106] that the sorry victim is led to the (sacrificial) altar to the applause of the crowd holding out its arms to (receive) the bonds of servitude.

It was thus not enough to set out in their majestic harmony the natural laws of the social order; it was also necessary to point out the disturbing factors[107] that paralyze their action. This is what I have endeavored to do in the second part of this book.[108]

I have striven to avoid controversy.[109] No doubt this made me miss the opportunity of providing the stability that comes from giving a more detailed discussion of the principles I wanted to promote. But would not the drawing of attention to digressions distract attention from the whole? If I reveal the structure as it is, what does it matter how others have seen it, even to those who (originally) taught me to see it?[110]

And now I appeal with confidence to men of all schools of thought who place justice, the general good, and truth above their (own) theories.

Economists, like you I am in favor of Freedom; and if I have shaken a few of those premises that sadden your generous hearts, perhaps you will see in this work one more reason to love and serve our holy cause.

Socialists, you have placed your faith in Association.[111] I plead with you to say, once you have read this work, whether current society as it already is, minus its abuses and hindrances, that is to say, in a climate of freedom, is not the finest, the most complete and long-lasting, the most universal and equitable of all associations.[112]

Egalitarians, you only accept one principle, the mutual exchange of services.[113] Let human transactions be freely made, and I will say that they are not and never can be anything other than a reciprocal exchange of services that constantly decrease in value[114] and constantly increase in utility.[115]

Communists, you want men, once they have become brothers, to enjoy in common the benefits that Providence has bestowed upon them. I intend to show that society as it already is has merely to make freedom a reality in order to achieve and exceed your wishes and hopes, for it makes everything available to all its members,[116] on the sole condition that each person takes the trouble to accept the gifts of God, which is an easy enough thing, or to freely recompense those who undertake this trouble on his behalf, which is only just.

Christians of all denominations, unless you are the only ones who cast doubt on Divine wisdom, revealed in the most magnificent of His works which have been given to us, you will not find in this essay a single line that is in conflict with the most strict of your moral codes or your most mysterious dogmas.[117]

Property-owners, whatever the size of your possessions, if I show that your rights, now being contested, are limited, like those of the simplest manual worker, to receiving services in exchange for real services which have been actually provided by you or your forebears, this right will henceforward be founded on an unshakeable base.[118]

Proletarians, I have made a great effort to demonstrate that you obtain the fruits of the fields you do not own with less effort and trouble than if you were obliged to grow them through your (own) direct labor or if you had been given the land in its original state, before labor was expended getting it prepared for production.[119]

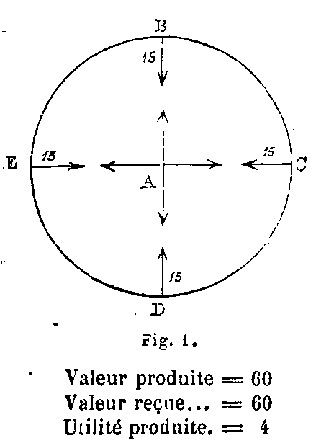

Capitalists and workers, I believe that I am in a position to establish the following law: “As capital is accumulated, the absolute share of capital to total production increases and its proportional share decreases; labor sees its relative share increase and, even more strongly, its absolute share. The contrary effect occurs when capital shrinks.”[120] When this law is established, its clear result is (that there is) (a) harmony of interests between laborers and those who employ them.[121]

Disciples of Malthus, sincere and much disparaged philanthropists, whose only error has been to warn the human race against a law which you (genuinely) believed to be fatal, I will have to give you a more comforting law: “All other things being equal,[122] the increasing density of the population represents an increasing ability to produce.” And if this is so, it will certainly not be you who will be sorry to see the crown of thorns fall from the brow of our beloved economic science.[123]

Men who live by plunder,[124] you who by (means) of force or fraud, either by scorning the law or by making use of it, are growing fat on the food of the people; you who make a living from the errors you spread, the ignorance you foster, the wars you start, or the obstacles you put in the way of transactions; you who impose taxes on labor after making it unproductive and making it lose more “sheafs of wheat” than you (are able) to extort from them in “ears of wheat;”[125] you who see to it that you are paid for creating obstacles (in the first place) so that later you can be paid for removing some of them; you who are the living examples of egoism in its worst sense, parasitic growths (which live off) distorted policies,[126] get your corrosive ink ready for the criticism (of me you will inevitably write); to you alone will I not appeal, for the aim of this book is to get rid of you, or rather your unjust claims. It is no use being in favor of conciliation; there are two principles that can never be reconciled: freedom and coercion.

If the laws of Providence are harmonious, it is (only) when they act freely, otherwise they would not be harmonious in themselves. Therefore, when we note a lack of harmony in the world it can only be the result of a lack of freedom or an absence of justice. Oppressors, plunderers, those who hold justice in contempt, you can never be part of universal harmony since you are the people who are upsetting it.

Is this to say that the effect of this book might be to weaken the government, to undermine its stability, or reduce its authority? The goal in my sight is quite the contrary. But let us understand each other fully.

Political science consists in perceiving what ought to be and what ought not to be included in the powers of the state,[127] and setting out on this major journey, you should not lose sight of the fact that the state always acts by means of the use of force. It imposes on us at the same time both the services it provides and the services it makes us pay in return in the form of taxes.[128]

The question can be summed up thus: What things have men the right to impose on one another by force? Well, I know of just one that comes into this category, and that is justice. I have no right to force anyone to be religious, charitable, educated, or hardworking, but I do have the right to force him to be just. This is the case of legitimate self-defense.[129]