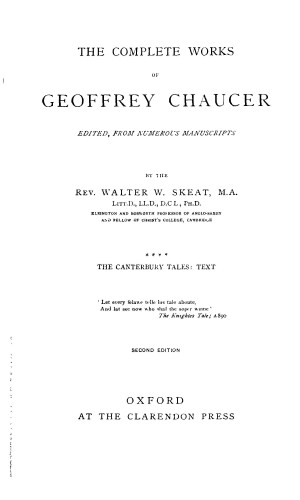

Part of: The Complete Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, 7 vols. The Complete Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, vol. 4 (The Canterbury Tales)

- Geoffrey Chaucer (author)

- Walter W. Skeat (editor)

The late 19th century Skeat edition with copious scholarly notes and a good introduction to the text. The Tales are in their original Middle English.