William Paley dismisses as a fiction the idea that there ever was a binding contract by which citizens consented to be ruled by their government (1785)

Found in: The Principles of Moral and Political Philosophy

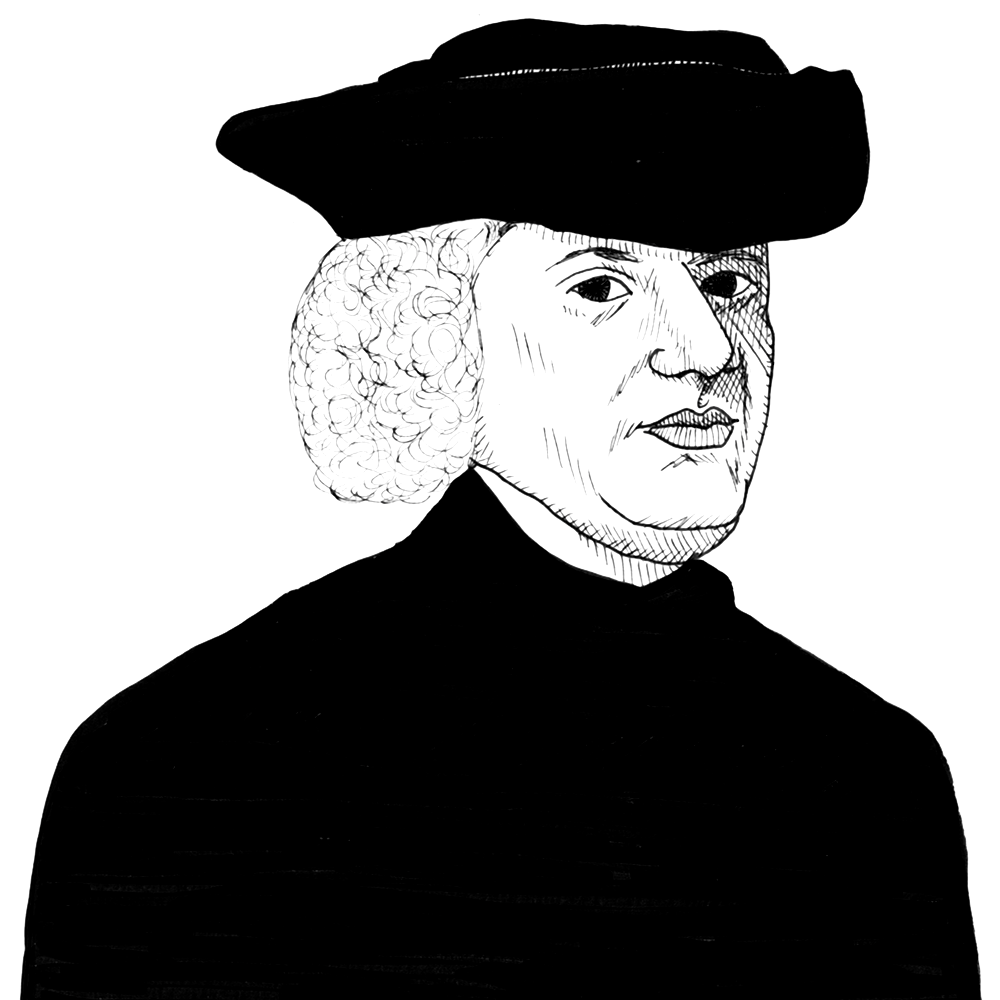

The English moral philosopher William Paley (1743-1805) debunks the idea that there ever was a binding “contract” by which the inhabitants of a country ever “consented” to be ruled by their rulers:

Origin of Government

Smoothly as this train of argument proceeds, little of it will endure examination. The native subjects of modern states are not conscious of any stipulation with the sovereigns, of ever exercising an election whether they will be bound or not by the acts of the legislature, of any alternative being proposed to their choice, of a promise either required or given; nor do they apprehend that the validity or authority of the law depends at all upon their recognition or consent. In all stipulations, whether they be expressed or implied, private or public, formal or constructive, the parties stipulating must both possess the liberty of assent and refusal, and also be conscious of this liberty; which cannot with truth be affirmed of the subjects of civil government as government is now, or ever was, actually administered. This is a defect, which no arguments can excuse or supply: all presumptions of consent, without this consciousness, or in opposition to it, are vain and erroneous.