Viscount Bryce on how the President in wartime becomes “a sort of dictator” (1888)

Found in: The American Commonwealth, vol. 1

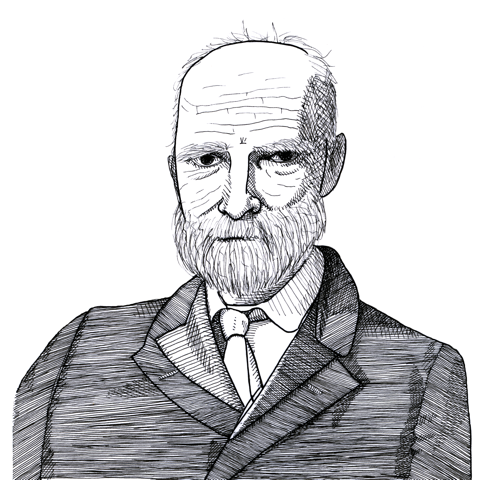

The British jurist, historian, and statesman Viscount James Bryce (1838-1922) observed as early as 1888 that “in troublous times” the powers the American President had at his disposal made him “a sort of dictator” which had not been seen in the English-speaking world since the time of Oliver Cromwell:

Presidents, Kings, Tyrants, & Despots

The direct domestic authority of the president is in time of peace very small, because by far the larger part of law and administration belongs to the state governments, and because federal administration is regulated by statutes which leave little discretion to the executive. In war time, however, and especially in a civil war, it expands with portentous speed. Both as commander in chief of the army and navy, and as charged with the “faithful execution of the laws,” the president is likely to be led to assume all the powers which the emergency requires. How much he can legally do without the aid of statutes is disputed, for the acts of President Lincoln during the earlier part of the War of Secession, including his proclamation suspending the writ of habeas corpus, were subsequently legalized by Congress; but it is at least clear that Congress can make him, as it did make Lincoln, almost a dictator….

In quiet times the direct legal power of the president is not great… In troublous times it is otherwise, for immense responsibility is then thrown on one who is both the commander in chief and the head of the civil executive. Abraham Lincoln wielded more authority than any single Englishman has done since Oliver Cromwell. It is true that the ordinary law was for some purposes practically suspended during the War of Secession. But it might again have to be similarly suspended, and the suspension makes the president a sort of dictator.

Although few presidents have shown any disposition to strain their authority, it has often been the fashion in America to be jealous of the president’s action, and to warn citizens against what is called “the one man power.”