Thomas Paine on the absurdity of an hereditary monarchy (1791)

Found in: The Writings of Thomas Paine, Vol. II (1779-1792)

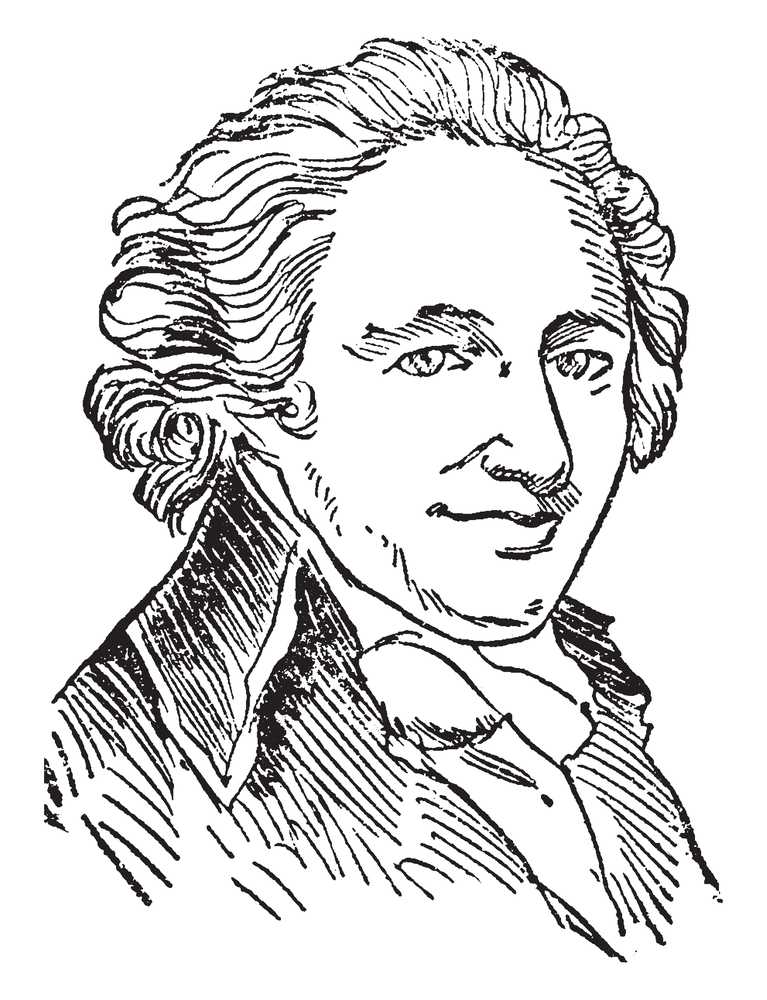

After having helped the American colonists shake off their reluctance to secede from the British Empire, Thomas Paine (1737-1809) turned his attention to the French Revolution which he vigorously defended against attacks by Edmund Burke. In the Rights of Man (1791) he distinguished between two types of government - the “representative” which was flourishing in North America, and the “hereditary” which still prevailed in Britain and France. He had the following harsh things to say about having an hereditary monarch:

Presidents, Kings, Tyrants, & Despots

We have heard the Rights of Man called a levelling system; but the only system to which the word levelling is truly applicable, is the hereditary monarchical system. It is a system of mental levelling. It indiscriminately admits every species of character to the same authority. Vice and virtue, ignorance and wisdom, in short, every quality, good or bad, is put on the same level. Kings succeed each other, not as rationals, but as animals. It signifies not what their mental or moral characters are. Can we then be surprised at the abject state of the human mind in monarchical countries, when the government itself is formed on such an abject levelling system?—It has no fixed character. To-day it is one thing; to-morrow it is something else. It changes with the temper of every succeeding individual, and is subject to all the varieties of each. It is government through the medium of passions and accidents. It appears under all the various characters of childhood, decrepitude, dotage, a thing at nurse, in leading-strings, or in crutches. It reverses the wholesome order of nature. It occasionally puts children over men, and the conceits of non-age over wisdom and experience. In short, we cannot conceive a more ridiculous figure of government, than hereditary succession, in all its cases, presents.