Richard Price on how the “domestic enemies” of liberty have been more powerful and more successful than foreign enemies (1789)

Found in: A Discourse on the Love of Our Country

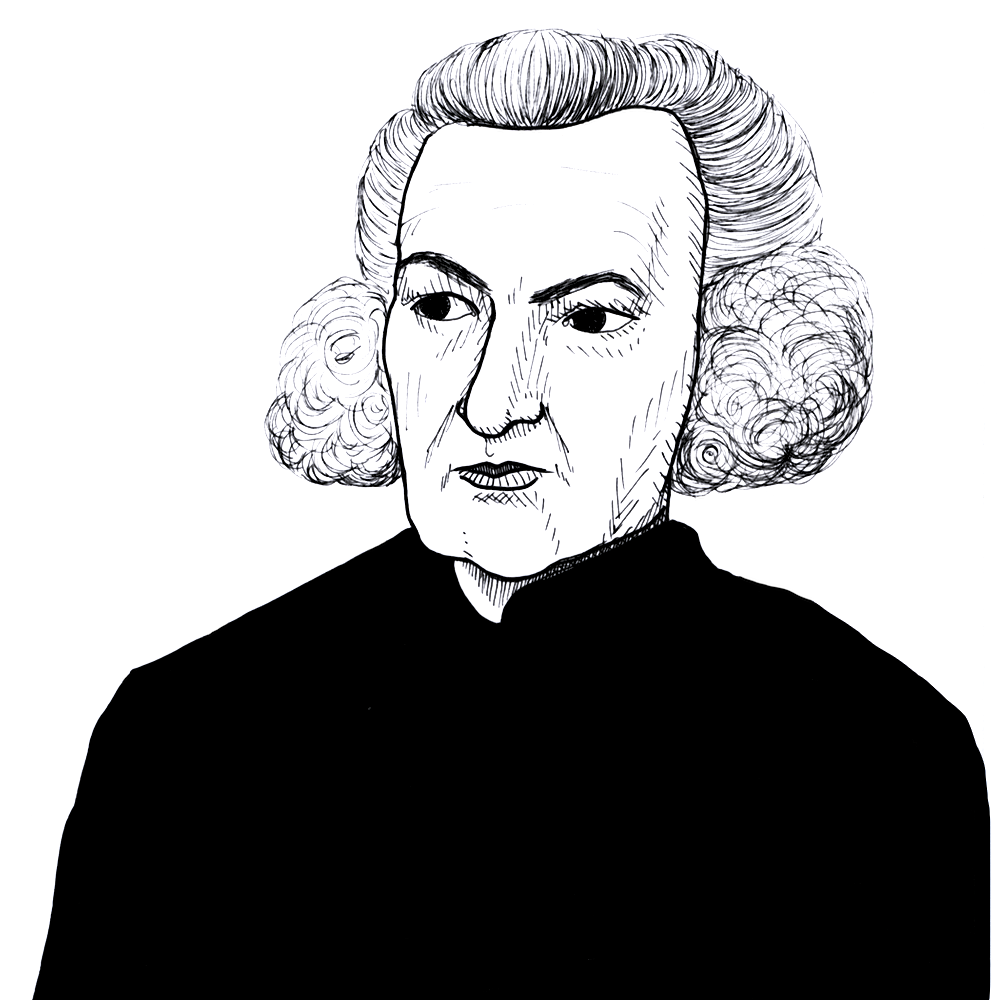

The Welsh Presbyterian minister Richard Price (1723-1791) in his Discourse celebrating the Revolution of 1688 in Britain warns about the dangers to liberty posed by ambitious “executive officers of government”:

War & Peace

Another expression of our love to our country is defending it against enemies. These enemies are of two sorts, internal and external; or domestic and foreign. The former are the most dangerous, and they have generally been the most successful. I have just observed, that there is a submission due to the executive officers of government, which is our duty; but you must not forget what I have also observed, that it must not be a blind and slavish submission. Men in power (unless better disposed than is common) are always endeavouring to extend their power. They hate the doctrine, that it is a trust derived from the people, and not a right vested in themselves. For this reason, the tendency of every government is to despotism; and in this the best constituted governments must end, if the people are not vigilant, ready to take alarms, and determined to resist abuses as soon as they begin. This vigilance, therefore, it is our duty to maintain. Whenever it is withdrawn, and a people cease to reason about their rights and to be awake to encroachments, they are in danger of being enslaved, and their servants will soon become their masters.