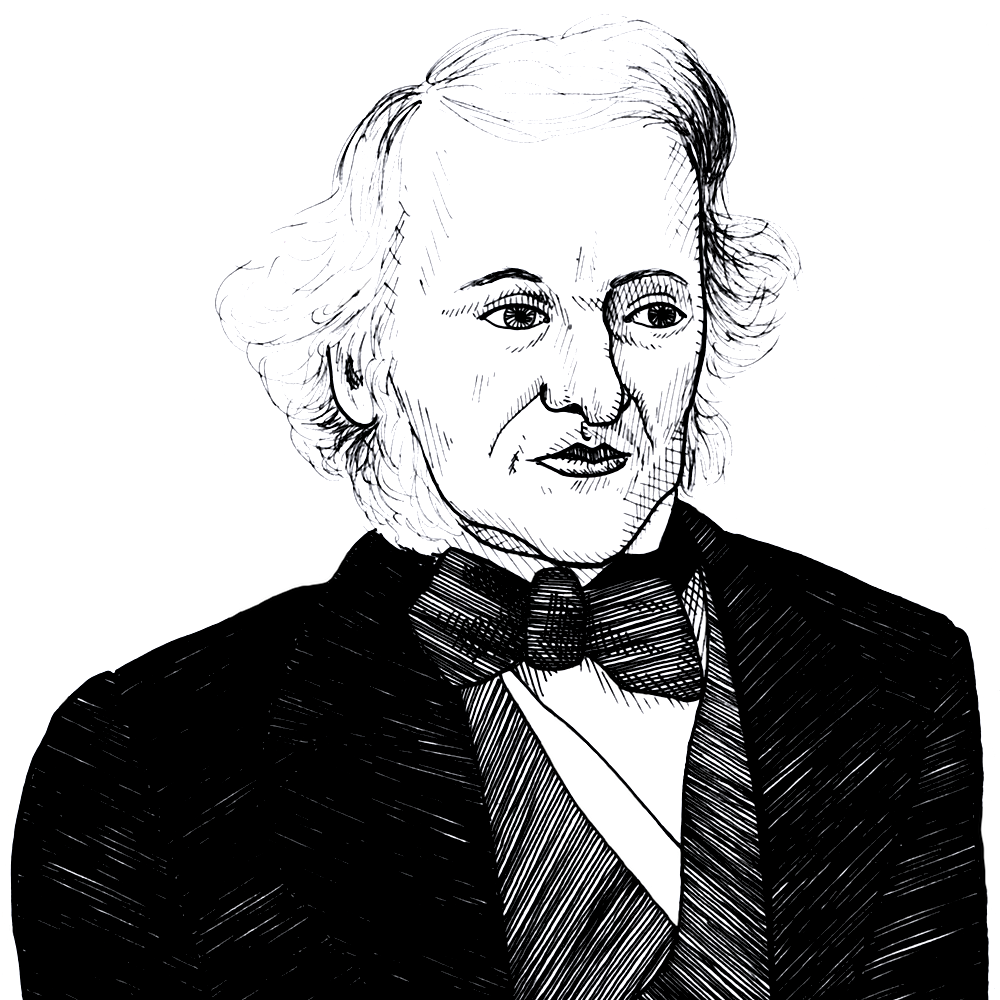

Richard Cobden on how free trade would unite mankind in the bonds of peace (1850)

Found in: Speeches on Questions of Public Policy, vol. 2

Richard Cobden (1804-1865) did not advocate free trade just because it would increase the production of goods, but primarily on the moral grounds that it would reduce violence and “unite mankind in the bonds of peace”:

Free Trade

But when I advocated Free Trade, do you suppose that I did not see its relation to the present question, or that I advocated Free Trade merely because it would give us a little more occupation in this or that pursuit? No; I believed Free Trade would have the tendency to unite mankind in the bonds of peace, and it was that, more than any pecuniary consideration, which sustained and actuated me, as my friends know, in that struggle. And it is because I want to see Free Trade, in its noblest and most humane aspect, have full scope in this world, that I wish to absolve myself from all responsibility for the miseries caused by violence and aggression, and too often perpetrated under the plea of benefiting trade.