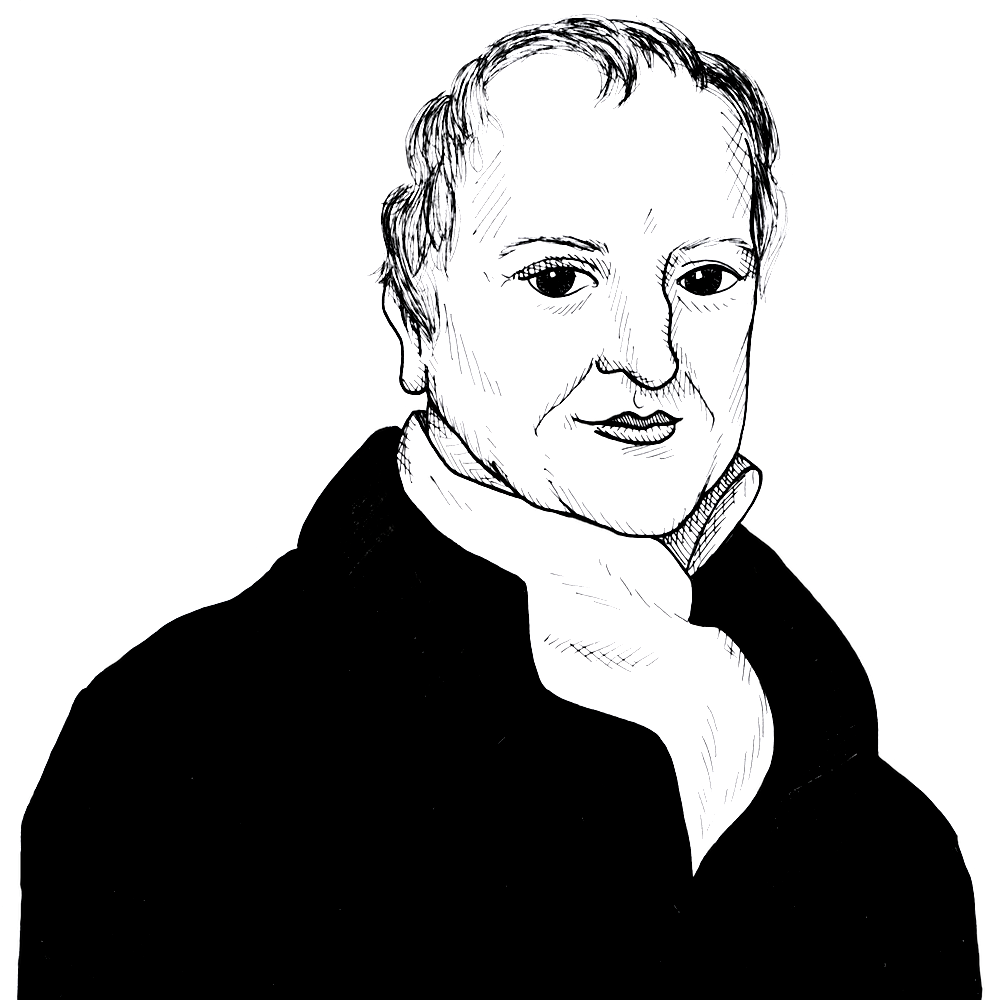

David Ricardo, Paper Money, and the Abuse of Power

Found in: The Works of David Ricardo (McCulloch ed. 1846, 1888)

It is commonly accepted that modern finances started with the establishment of the Bank of England (BoE) in 1694. In exchange for securing a loan from a group of merchants, the Crown asked Parliament to give the bank a charter that would allow them to issue banknotes that would be accepted in payment of taxes owed to the crown. Those banknotes would be redeemable in gold coins on demand by the bank, and with that, a system by which money began to be supplied both by government, in the form of metal coins and by the commercial banks in the form of banknotes redeemable in gold or silver coins took shape.

Economics

Experience, however, shows that neither a State nor a Bank ever have had the unrestricted power of issuing paper money without abusing that power: in all States, therefore, the issue of paper money ought to be under some check and control; and none seems so proper for that purpose as that of subjecting the issuers of paper money to the obligation of paying their notes either in gold coin or bullion. (FROM CHAPTER XXVII.: ON CURRENCY AND BANKS)