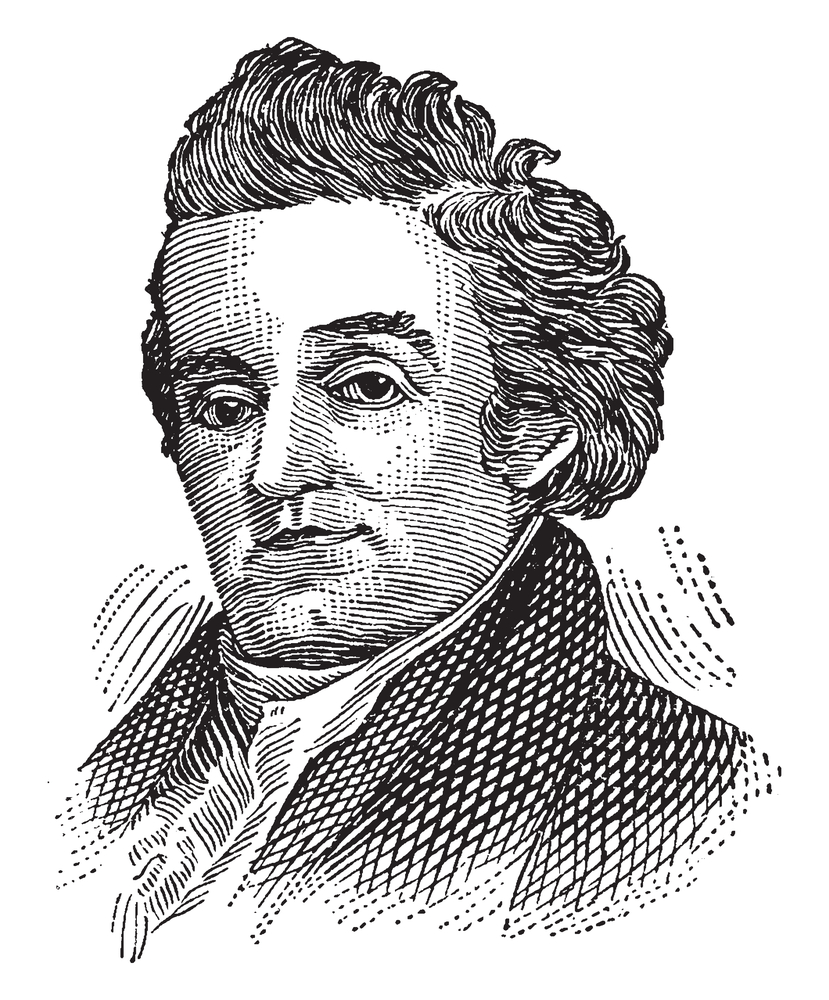

Noah Webster on the resilience of common religious practices in the face of attempts by the state to radically change them (1794)

Found in: Political Sermons of the American Founding Era. Vol. 2 (1789-1805)

In a sermon given at the height of the French Terror, Noah Webster (1758-1843) noted the failure of attempts by the state or established church to change the way ordinary people practiced their religion. Whether it was the Egyptians, the Greeks, the Roman Catholic Church, or the Jacobins in Paris, the result was much the same. The ordinary people continued to practice their traditional beliefs with a universal passion for feasting and gift giving:

Religion & Toleration

The Romans had a celebrated festival, called Saturnalia in honor of Saturn; this festival found its way into antient Scandinavia, among our pagan ancestors, by whom it was new-modelled or corrupted, being kept at the winter solstice. The night on which it was kept was called mother-night, as that which produced all the rest; and the festival was called Iuule or Yule. The christians, not being able to abolish the feast, changed its object, gave it the name of Christmas, and kept it in honor of Jesus Christ, altho the ancient name yule was retained in some parts of Scotland, till within a century. … What is the deduction from these facts? This certainly, that men have uniformly had a high veneration for some person or deity real or imaginary: the Romans for Saturn: the Goths for the mother-night of the year; and the christians for the founder of their religion. The christians have the advantage over the pagans in appropriating the feast to a nobler object; but the passion is the same, and the joy, the feasting, and the presents that have marked the festival are nearly the same among pagans and christians.