Nassau Senior argues that government is based upon extortion (1854)

Found in: Political Economy (1850 ed.)

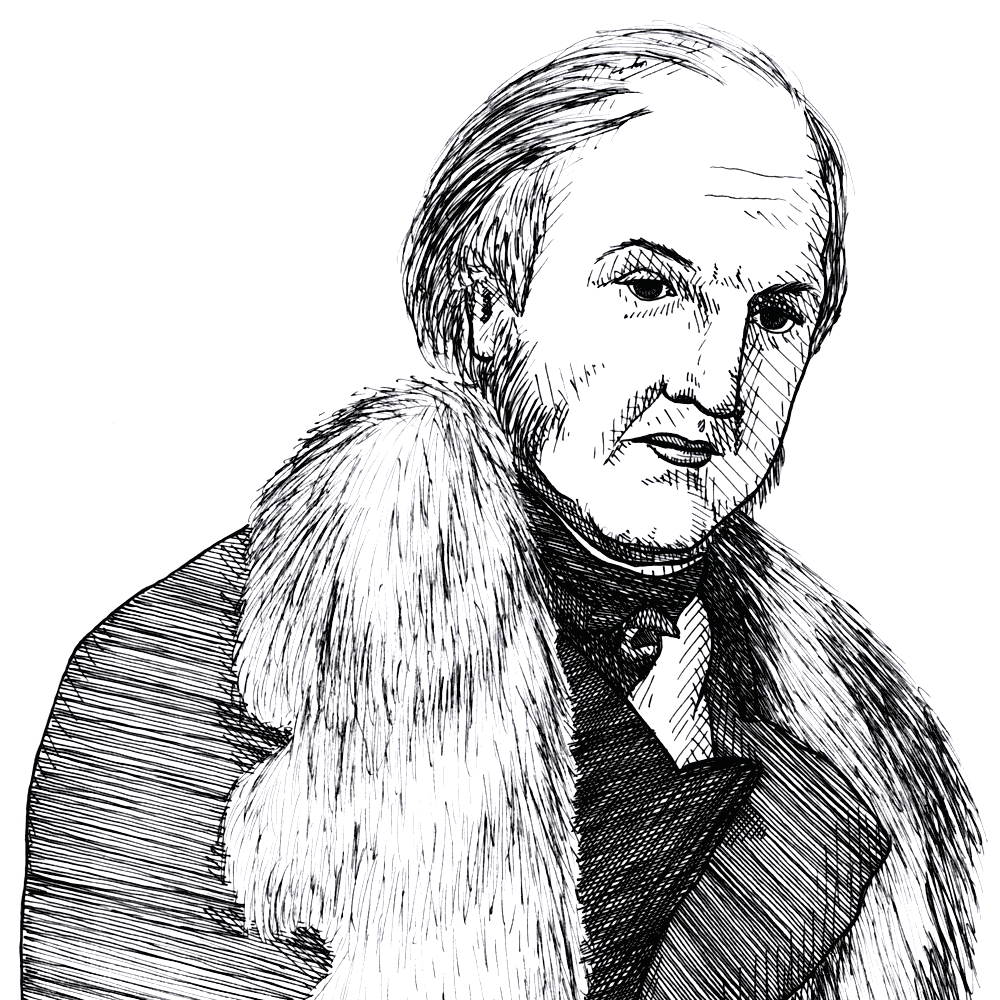

In his general introduction to the science of political economy Nassau W. Senior (1790-1864) applies the principle of the division of labor to the functions of government and concludes that it behaves very differently from other exchanges in the market in that it extorts much more than the fair value of the service it provides:

The State

It is obvious, however, that the division of labour on which government is founded, is subject to peculiar evils. Those who are to afford protection must necessarily be intrusted with power; and those who rely on others for protection lose, in a great measure, the means and the will to protect themselves. Under such circumstances, the bargain, if it can be called one, between the government and its subjects, is not conducted on the principles which regulate ordinary exchanges. The government generally endeavours to extort from its subjects, not merely a fair compensation for its services, but all that force or terror can wring from them without injuring their powers of further production. In fact, it does in general extort much more: for if we look through the world we shall find few governments whose oppression does not materially injure the prosperity of their people.