Molinari on the elites who benefited from the State of War (1899)

Found in: The Society of Tomorrow

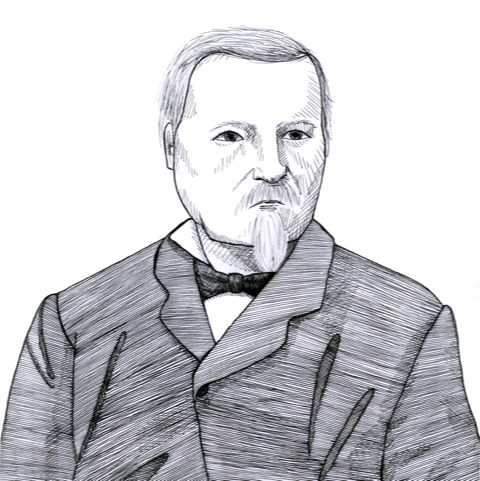

The French economist Gustave de Molinari (1819-1912) concluded in 1899 that wars would continue to be fought, in spite of their growing cost in terms of destruction wrought, lives lost, and high taxes, as long as powerful groups within society benefited personally from such a situation. To his mind, this meant the powerful political, bureaucratic, and military elites which controlled European societies at the end of the 19th century:

Class

Every State includes a governing class and a governed class. The former is interested in the immediate multiplication of employments open to its members, whether these be harmful or useful to the State, and also desires to remunerate these officials at the best possible rate. But the majority of the nation, the governed class, pays for the officials, and its only desire is to support the least necessary number. A State of War, implying an unlimited power of disposition over the lives and goods of the majority, allows the governing class to increase State employments at will—that is, to increase its own sphere of employment. A considerable portion of this sphere is found in the destructive apparatus of the civilised State—an organism which grows with every advance in the power of the rivals. In time of peace the army supports a hierarchy of professional soldiers, whose career is highly esteemed, and is assured if not particularly remunerative. In time of war the soldier obtains an additional remuneration, more glory, and an increased hope of professional advancement, and these advantages more than compensate the risks which he is compelled to undergo. In this way a State of War continues to be profitable both to the governing class as a whole, and to those officials who administer and officer the army.