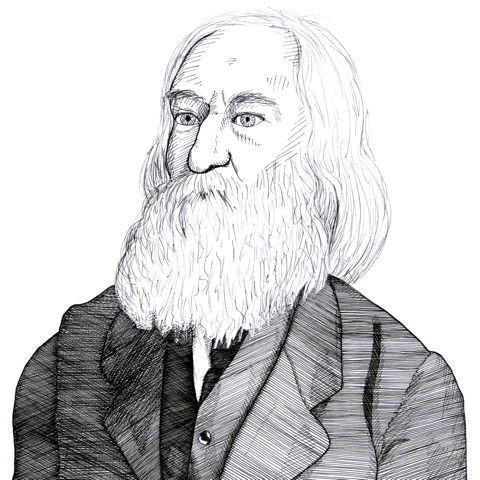

Lysander Spooner on Jury Nullification as the "palladium of liberty" against the tyranny of government (1852)

Found in: An Essay on the Trial by Jury (1852)

Lysander Spooner (1808-1887) argued in Trial by Jury (1852) that juries had the right and the duty to judge the justice of the law and to thereby act as a "palladium of liberty" against the tyranny of government:

Law

It is manifest, therefore, that the jury must judge of and try the whole case, and every part and parcel of the case, free of any dictation or authority on the part of the government. They must judge of the existence of the law; of the true exposition of the law; of the justice of the law; and of the admissibility and weight of all the evidence offered; otherwise the government will have everything its own way; the jury will be mere puppets in the hands of the government; and the trial will be, in reality, a trial by the government, and not a “trial by the country.” By such trials the government will determine its own powers over the people, instead of the people’s determining their own liberties against the government; and it will be an entire delusion to talk, as for centuries we have done, of the trial by jury, as a “palladium of liberty,” or as any protection to the people against the oppression and tyranny of the government.