Lord Acton argues that civil liberty arose out of the conflict between the power of the Church and the Monarchy (1877)

Found in: The History of Freedom and Other Essays

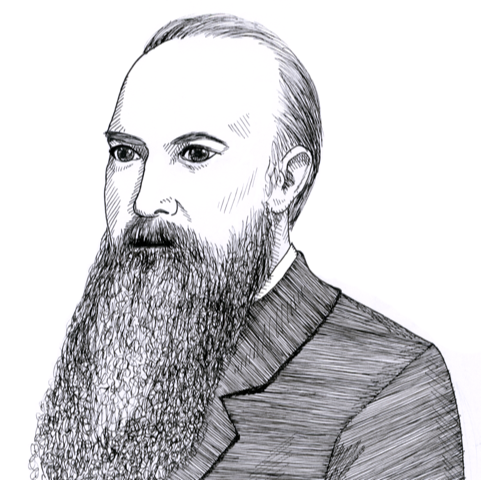

The English Catholic historian Lord Acton (1834-1902) believed that liberty emerged almost as an unintended by-product of the conflict between the Church and the monarchies of Europe for absolute authority over the course of nearly 400 years:

Religion & Toleration

The only influence capable of resisting the feudal hierarchy was the ecclesiastical hierarchy; and they came into collision, when the process of feudalism threatened the independence of the Church by subjecting the prelates severally to that form of personal dependence on the kings which was peculiar to the Teutonic state.

To that conflict of four hundred years we owe the rise of civil liberty. If the Church had continued to buttress the thrones of the king whom it anointed, or if the struggle had terminated speedily in an undivided victory, all Europe would have sunk down under a Byzantine or Muscovite despotism. For the aim of both contending parties was absolute authority. But although liberty was not the end for which they strove, it was the means by which the temporal and the spiritual power called the nations to their aid.