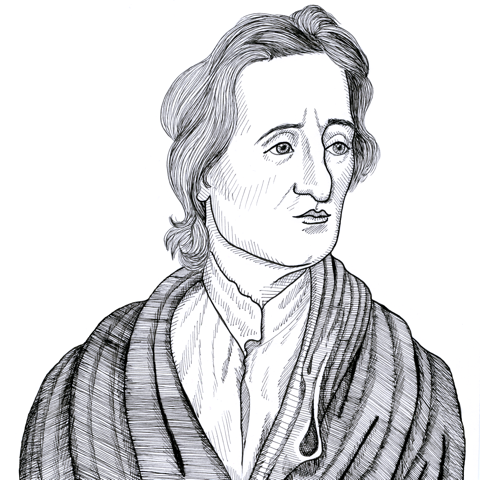

John Locke on the idea that “wherever law ends, tyranny begins” (1689)

Found in: The Two Treatises of Civil Government (Hollis ed.)

John Locke states in Section 202 of Chap. XVIII “Of Tyranny” in Book II of the Two Treatises of Government that even magistrates must abide by the law:

Law

Where-ever law ends, tyranny begins, if the law be transgressed to another’s harm; and whosoever in authority exceeds the power given him by the law, and makes use of the force he has under his command, to compass that upon the subject, which the law allows not, ceases in that to be a magistrate; and, acting without authority, may be opposed, as any other man, who by force invades the right of another. This is acknowledged in subordinate magistrates. He that hath authority to seize my person in the street, may be opposed as a thief and a robber, if he endeavours to break into my house to execute a writ, notwithstanding that I know he has such a warrant, and such a legal authority, as will impower him to arrest me abroad. And why this should not hold in the highest, as well as in the most inferior magistrate, I would gladly be informed.