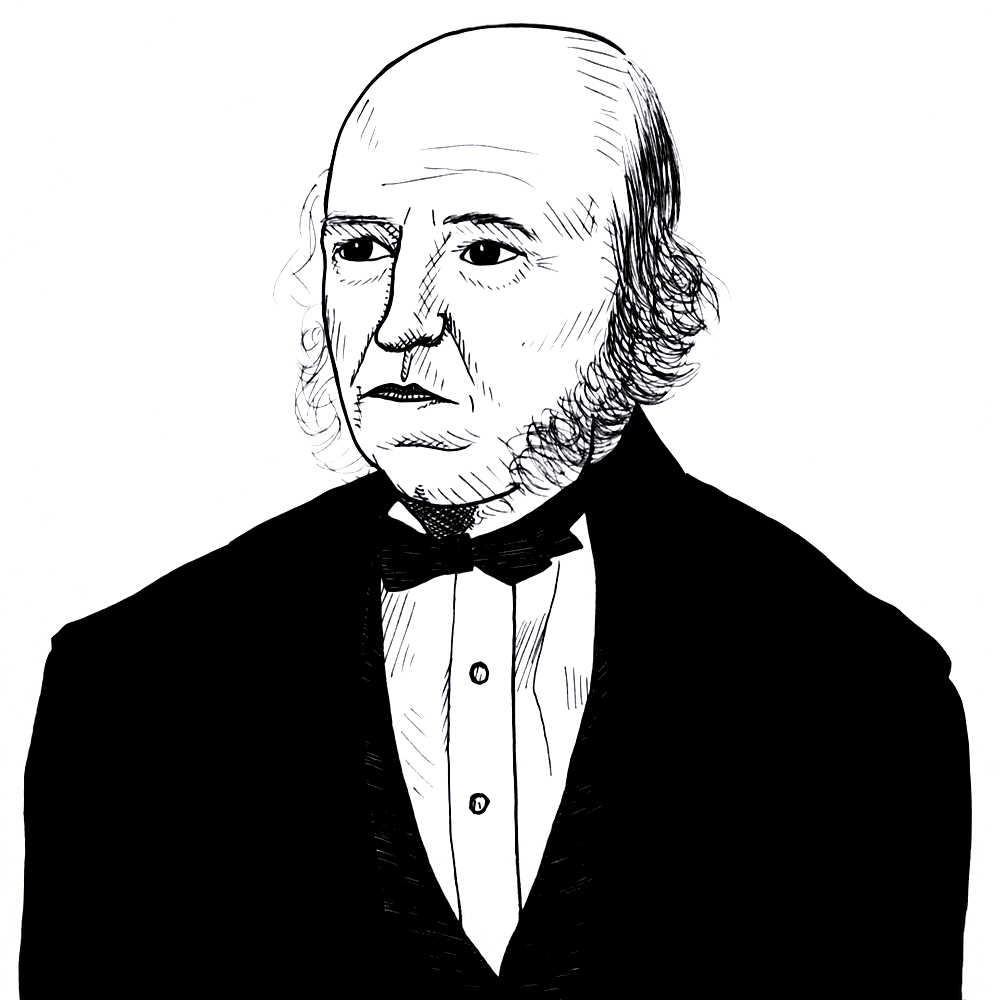

Herbert Spencer on the superiority of private enterprise over State activity (1853)

Found in: The Man versus the State, with Six Essays on Government, Society and Freedom (LF ed.)

The English individualist political theorist Herbert Spencer (1820-1903) wonders why, given the never ending stream of news about government incompetence and failure, people still call for it do do more:

Law

(T)hey seem to have read backwards the parable of the talents. Not to the agent of proved efficiency do they consign further duties, but to the negligent and blundering agent. Private enterprise has done much, and done it well. Private enterprise has cleared, drained, and fertilized the country, and built the towns; has excavated mines, laid out roads, dug canals, and embanked railways; has invented, and brought to perfection ploughs, looms, steam-engines, printing-presses, and machines innumerable; has built our ships, our vast manufactories, our docks; has established banks, insurance societies, and the newspaper press; has covered the sea with lines of steam-vessels, and the land with electric telegraphs. Private enterprise has brought agriculture, manufactures, and commerce to their present height, and is now developing them with increasing rapidity. Therefore, do not trust private enterprise. On the other hand, the State so fulfils its judicial function as to ruin many, delude others, and frighten away those who most need succor; its national defences are so extravagantly and yet inefficiently administered as to call forth almost daily complaint, expostulation, or ridicule; and as the nation’s steward, it obtains from some of our vast public estates a minus revenue. Therefore, trust the State. Slight the good and faithful servant, and promote the unprofitable one from one talent to ten.