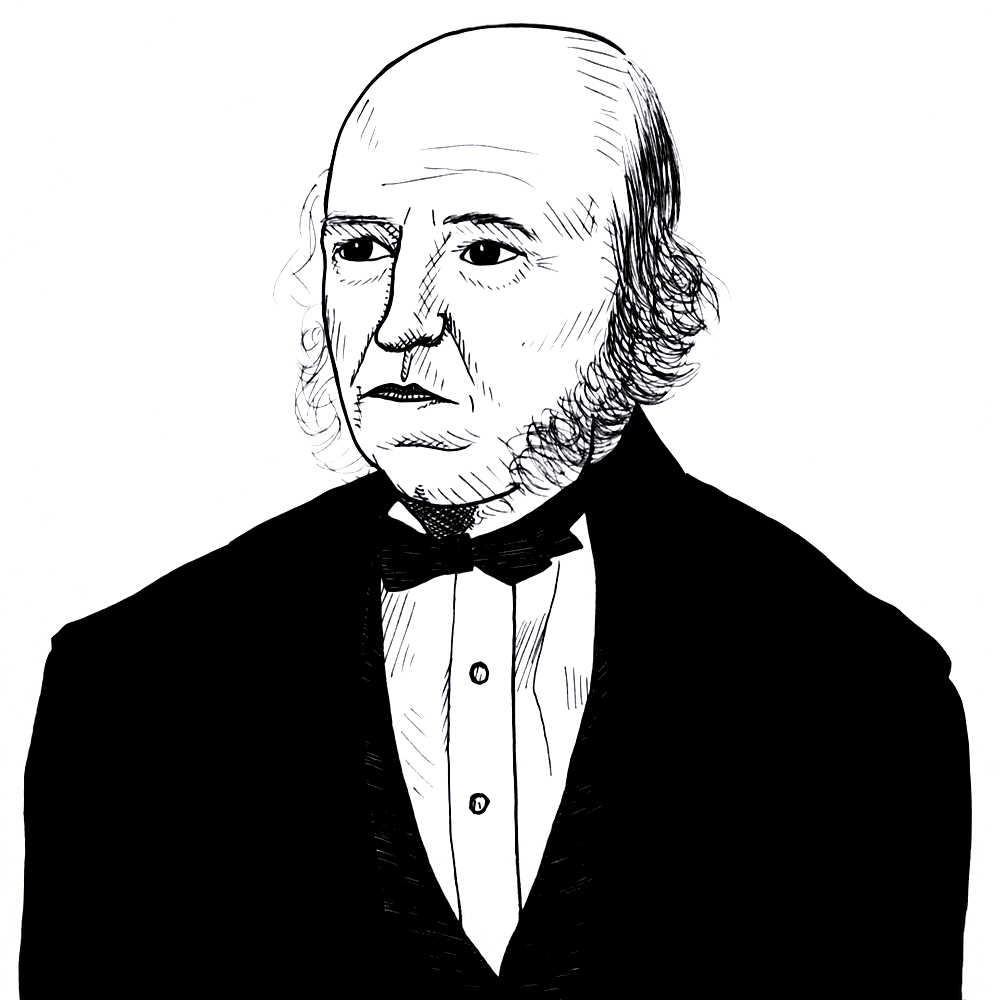

Herbert Spencer on the right of political and economic “dissenters” to have their different beliefs and practices respected by the state (1842)

Found in: The Man versus the State, with Six Essays on Government, Society and Freedom (LF ed.)

Herbert Spencer (1820-1903) argues that political and economic “dissenters” should have the same right as religious dissenters to have their different beliefs and practices respected by the state:

Natural Rights

The chief arguments that are urged against an established religion, may be used with equal force against an established charity. The dissenter submits, that no party has a right to compel him to contribute to the support of doctrines, which do not meet his approbation. The rate-payer may as reasonably argue, that no one is justified in forcing him to subscribe towards the maintenance of persons, whom he does not consider deserving of relief. The advocate of religious freedom, does not acknowledge the right of any council, or bishop, to choose for him what he shall believe, or what he shall reject. So the opponent of a poor law, does not acknowledge the right of any government, or commissioner, to choose for him who are worthy of his charity, and who are not. … So the dissenter from established charity, objects that no man has a right to step in between him and the exercise of his religion.