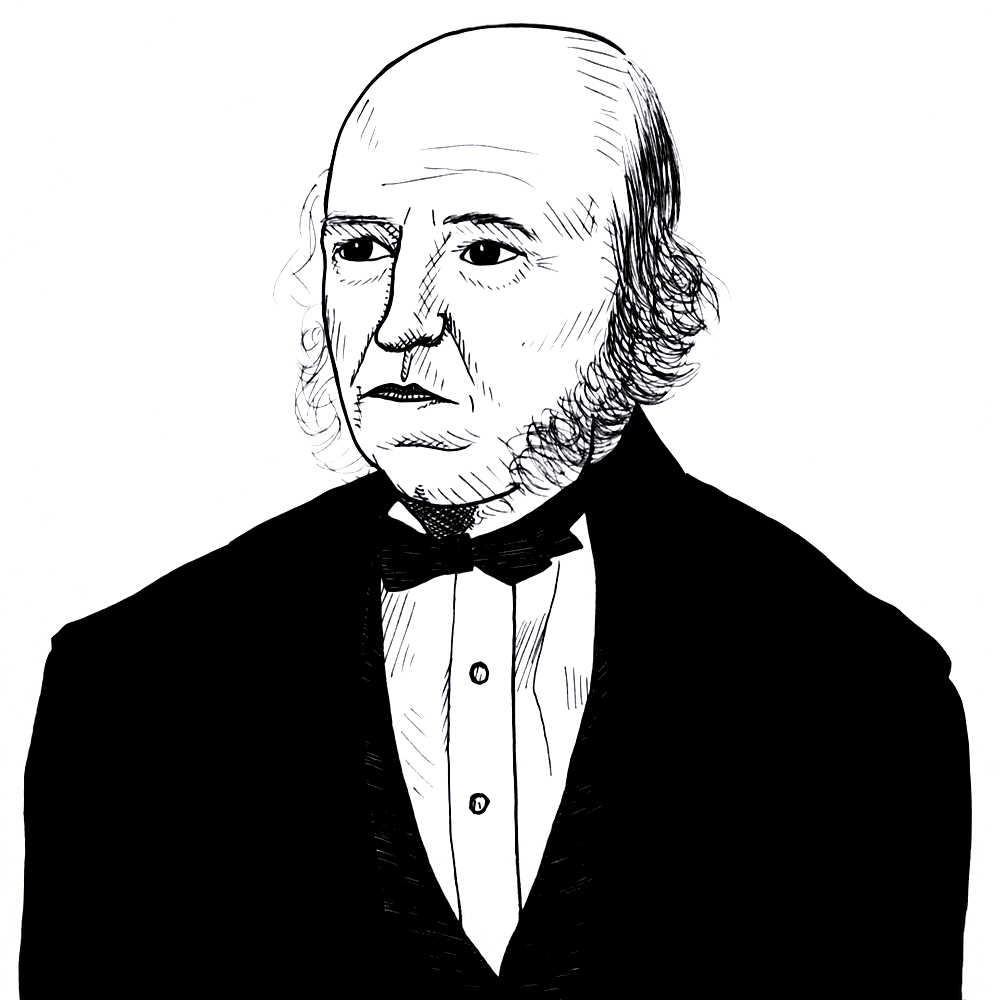

Herbert Spencer on human nature and the right to property (1851)

Found in: Social Statics (1851)

The English individualist political theorist Herbert Spencer (1820-1903) argues in Social Statics (1851) that people have a right to property on the grounds that it is a vital part of their human nature and that it would contradict the “law of equal freedom”:

Property Rights

An argument fatal to the communist theory, is suggested by the fact, that a desire for property is one of the elements of our nature. … And if a propensity to personal acquisition be really a component of man’s constitution, then that cannot be a right form of society which affords it no scope. … it is also true that no change in the state of society will alter its nature and its office. To whatever extent moderated, it must still be a desire for personal acquisition. Whence it follows that a system affording opportunity for its exercise must ever be retained; which means, that the system of private property must be retained; and this presupposes a right of private property, for by right we mean that which harmonizes with the human constitution as divinely ordained.