Guizot on man’s unquenchable desire for liberty and free political institutions (1820-22)

Found in: The History of the Origins of Representative Government in Europe

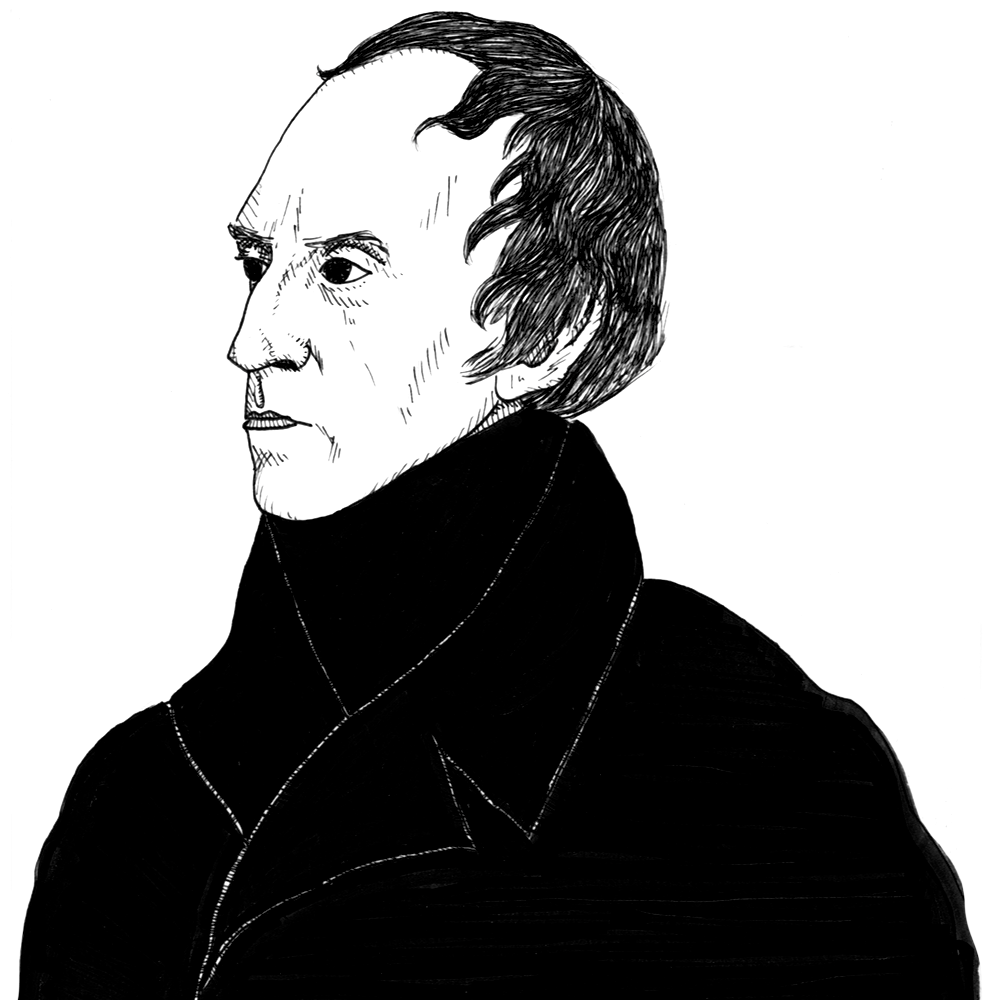

The French politician and liberal historian François Guizot (1787-1874) argued in 1822 that no matter what the outward form a government might be “there is an instinctive sense of justice and reason dwelling in every human spirit” which always bubbles to the surface to express the desire for liberty and free institutions such as representative government:

Liberty

At all times men have endeavoured to limit the power which they regarded as perfectly legitimate. Never has a force, although invested with the right of sovereignty, been allowed to develop that right to its full extent. The janissaries in Turkey sometimes served, sometimes abrogated, the absolute power of the Sultan. In democracies, where the right of sovereignty is vested in popular assemblies, efforts have been continually made to oppose conditions, obstacles, and limits to that sovereignty. Always, in all governments which are absolute in principle, some kind of protest has been made against the principle. Whence comes this universal protest? We might, looking merely at the surface of things, be tempted to say that it is only a struggle of powers. This has existed without doubt, but another and a grander element has existed along with it; there is an instinctive sense of justice and reason dwelling in every human spirit. Tyranny has been opposed, whether it were the tyranny of individuals or of multitudes, not only by a consciousness of power, but by a sentiment of right. It is this consciousness of justice and right, that is to say, of a rule independent of human will—a consciousness often obscure but always powerful—which, sooner or later, rouses and assists men to resist all tyranny, whatever may be its name and form. The voice of humanity, then, has proclaimed that the right of sovereignty vested in men, whether in one, in many, or in all, is an iniquitous lie.